MEXICAN WOLF

RECOVERY PROGRAM

A Mexican wolf pup is given a health check at a 2022 foster event. Credit: Mexican Wolf Interagency

Field Team

PROGRESS REPORT # 25

PREPARED BY: U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

COOPERATORS: ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT, NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF

GAME AND FISH, USDA-APHIS WILDLIFE SERVICES, U.S. FOREST SERVICE, AND WHITE

MOUNTAIN APACHE TRIBE

Mexican Wolf Recovery

Program

PROGRESS REPORT #25

Reporting period: January 1-December 31, 2022

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword ....................................................................................................................... 3

Background ................................................................................................................... 3

Part A: Recovery Administration ................................................................................ 4

1.

Mexican Wolf Captive Breeding Program ................................................... 4

2.

Recovery Plan Implementation / Progress Toward Recovery .................... 7

3.

Summary of Litigation ....................................................................................... 8

4. Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area Management Structure .. 10

5. Cooperative Agreements ............................................................................... 11

6.

Livestock Conflict Compensation Programs.................................................. 12

7.

Literature Cited ................................................................................................ 14

Part B: Reintroduction ................................................................................................ 15

1.

Key Developments ........................................................................................... 16

2.

Introduction ................................................................................................... 18

3.

Population Status ............................................................................................. 20

4.

Conflict

Management .................................................................................... 35

5.

Literature Cited ................................................................................................ 48

6.

Personnel ........................................................................................................ 50

Appendices .................................................................................................................. 52

Appendix A:

Mexican Wolf Pack Hom

e Range Details ...................................... 52

Appendix B:

Mexican Wolf Use Area

.................................................................... 56

3

FOREWORD

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is the lead agency responsible for recovery of the

Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), pursuant to the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended

(Act). The Mexican Wolf Recovery Program has two interrelated components: 1) Recovery – includes

aspects of the program administered by the Service with assistance from partner agencies that

pertain to the overall goal of Mexican wolf recovery and delisting from the list of threatened and

endangered species, and 2) Monitoring and Management – includes aspects of the program

implemented by the Service and cooperating States, Tribes, other Federal agencies, and counties that

pertain to the monitoring and management of the reintroduced Mexican wolf population in the

Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area (MWEPA). This report provides details on both aspects

of the Mexican Wolf Recovery Program. The reporting period for this progress report is January 1-

December 31, 2022.

BACKGROUND

The Mexican wolf is listed as endangered under the Act in the southwestern United States and

Mexico (80 FR 2488-2512, January 16, 2015). It is the smallest, rarest, southernmost occurring, and

most genetically distinct subspecies of the North American gray wolf (Canis lupus).

Mexican wolves were extirpated in the wild in the southwestern United States by 1970, following

several decades of private and governmental efforts to reduce predator populations due to conflict

with livestock. Recovery efforts for the Mexican wolf began in 1976 with its listing as an endangered

species. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the initiation of a binational captive breeding program

originating from seven wolves prevented the extinction of the Mexican wolf.

As recommended in the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, Second Revision (Service 2022) (Recovery

Plan), recovery efforts for the Mexican wolf focus on the reestablishment of two Mexican wolf

populations in the wild, one in the United States and one in Mexico, and on maintenance of the

captive breeding population. Mexican wolves were first released to the wild in the United States in

1998. In Mexico, Mexican federal agencies initiated a reintroduction effort in 2011 pursuant to

Mexico’s federal laws and regulations.

Today, the wild population in the United States is managed and monitored by an Interagency Field

Team (IFT) comprised of staff from the Service, Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD), New

Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF), White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT), U.S. Forest

Service, and U.S. Department of Agriculture-Wildlife Services (USDA-WS).

4

PART A: RECOVERY ADMINISTRATION

1. MEXICAN WOLF CAPTIVE BREEDING PROGRAM

a. Mexican Wolf Species Survival Plan

The Mexican Wolf Species Survival Plan (SSP) is a binational captive breeding program between

the United States and Mexico for the Mexican wolf. The SSP mission is to reestablish the Mexican

wolf in the wild through captive breeding, public education, and research. While Mexican wolves

are maintained in numerous captive facilities in both countries, they are managed as a single

population. SSP member institutions routinely transfer Mexican wolves among participating facilities

for breeding to promote genetic exchange and maintain the health and genetic diversity of the

captive population. Wolves in these facilities are managed in accordance with a Service-approved

standard protocol. Without the SSP, recovery of the Mexican wolf would not have been possible.

Mexican wolf m1888 recovers after surgery at the Albuquerque BioPark veterinary clinic

.

Credit: Courtesy of ABQ BioPark.

This year, the SSP’s binational meeting to plan and coordinate wolf breeding, transfers, and related

activities among facilities was held virtually. The meeting included updates on the reintroduced

populations in the US and Mexico, discussion on gamete banking needs, evaluation and selection of

release candidates for both the United States and Mexico, and reports on research including

advances in gamete banking, contraception and assisted reproductive technologies, and progress

toward a lifetime reproductive plan for wolves to maximize an individual’s potential to contribute to

the population.

As of July 2022, the SSP population includes 366 Mexican wolves managed in approximately 57

5

facilities in th

e United States and Mexico. The SSP goal is to house a minimum of 240 wolves, with a

target population size of 300, to ensure the security of the subspecies in captivity and produce

animals for reintroduction.

The SSP population has served as the sole source population to reestablish the subspecies in the wild.

Mexican wolves released to the wild from the SSP population also serve a critically important role in

improving the gene diversity of the wild population. Wolves that are considered genetically well-

represented in the SSP population may be designated for release. Suitable release candidates are

determined based on criteria such as genetic makeup, reproductive performance, behavior, and

physical suitability. We perform analyses to ensure the released wolves are beneficial to the genetic

diversity of the wild population while minimizing adverse effects to the genetic integrity of the

captive population if wolves released to the wild do not survive. Since 2016, the Service and its

partners have focused on fostering as the primary release method in the United States. While much

consideration is given to breeding captive wolves that will produce pups that genetically benefit the

wild population, the selection of pups to use in fostering efforts is ultimately determined by timing

and synchrony of wild and captive litters. See below (page 25; releases and translocations) for more

discussion on fostering.

b. Mexican Wolf Pre-Release Facilities

Prior to release to the wild, Mexican wolves are acclimated in captive facilities designed to house

wolves in a manner that fosters wild behaviors (e.g., increasing natural fear of human presence, and

acclimatation to an intermittent, unpredictable feeding regimen). The Service oversees the

management at the Ladder Ranch and Sevilleta Wolf Management Facilities, located in New

Mexico. At these facilities, wolves are managed with minimal exposure to humans in order to minimize

habituation to humans and maximize pair bonding, breeding, pup rearing, and healthy pack

structure development. These facilities have been successful in breeding wolves for release (including

pups for fostering) and are integral to Mexican wolf recovery efforts. To further minimize

habituation to humans, public visitation to the Ladder Ranch and Sevilleta facilities is not permitted.

Release candidates are fed carnivore logs and a zoo-based exotic canine diet formulated for wild

canids. In addition, we supplement their diet with carcasses of road-killed ungulate species, such as

deer and elk, and scraps (meat, organs, hides, and bones) from local game processors from wild

game/prey species only. Release candidates are given annual examinations to vaccinate for canine

diseases (e.g., parvo, adeno2, parainfluenza, distemper, and rabies viruses, etc.), are dewormed,

have laboratory evaluations performed, and have their overall health condition evaluated. Animals

are treated for other veterinary purposes on an as-needed basis.

Sevilleta Wolf Management Facility

The Sevilleta Wolf Management Facility (Sevilleta) is located on the Sevilleta National Wildlife

Refuge near Socorro, New Mexico and is managed by the Service. There are a total of eight

enclosures, ranging in size from 0.25 acre to approximately 1.25 acres, and a quarantine pen.

National Wildlife Refuge staff assist Mexican Wolf Recovery Program staff in the maintenance and

administration of the wolf pens.

Twenty-two Mexican wolves were housed at the Sevilleta during 2022. These wolves were

6

maintained in v

arious social groups including adults with pups, breeding pairs, sibling groups, and

single wolves. The wolves housed at the Sevilleta contributed to all three Mexican wolf populations

managed for recovery. Twenty-one percent of management activities supported recovery efforts in

the United States by housing wolves for release in the MWEPA (foster pups), and housing wolves

removed from the MWEPA. Sixty-one percent of management activities supported the Mexican Wolf

SSP’s mission of maintaining Mexican wolves in captivity to support recovery efforts. Eighteen

percent of management activities supported recovery efforts in Mexico by preparing wolves for

direct release into the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains (SMOCC) in Mexico.

Ladder Ranch Wolf Management Facility

The Ladder Ranch Wolf Management Facility (Ladder Ranch), owned by R. E. Turner, is located on

the Ladder Ranch near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. The facility consists of five enclosures,

ranging in size of 0.3 acre to approximately 0.70 acre. The caretaking of wolves at the facility is

carried out by an employee of the Turner Endangered Species Fund, though the facility is managed

and supported financially by the Service.

Sixteen Mexican wolves were housed at the Ladder Ranch during 2022. These wolves were

maintained in various social groups including adult pairs, sibling and yearling groups, and single

wolves. These wolves contributed to all three Mexican wolf populations managed for recovery. Four

percent of management activities supported recovery efforts in the United States by housing wolves

removed from the MWEPA. Fifty-six percent of management activities supported the Mexican Wolf

SSP’s mission of maintaining Mexican wolves in captivity to support recovery efforts. Forty percent of

management activities supported recovery efforts in Mexico by preparing wolves for direct release

into the SMOCC in Mexico.

A Mexican wolf stands inside an enclosure at the Ladder Ranch Wolf Management

Facility. Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

7

2. RECOVERY PLAN IMPLEMENTATION / PROGRESS TOWARD RECOVERY

The Recovery Plan provides downlisting and delisting criteria for the Mexican wolf, as well as

recovery actions that, if implemented, will achieve the criteria (Service 2022, pp. 19-21, 29-35). To

assist the Service and our partners in the implementation of the Recovery Plan, we developed a

Recovery Implementation Strategy (RIS) https://www.fws.gov/library/collections/mexican-wolf-

recovery-planning-documents. We intend to update the RIS as needed during recovery.

In 2022, we implemented a number of recovery actions associated with the objectives in the RIS;

including: survey and monitor Mexican wolves to determine population status including Mexican

wolves on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation and San Carlos Apache Reservation; reduce Mexican

wolf- livestock conflicts; develop plans for and implement releases (via fostering) and translocation

of Mexican wolves; monitor the genetic health of the population; and, manage the captive

breeding/SSP population. See Part B of this report for more detail on these activities as they pertain

to management of the Mexican wolves in the MWEPA.

Recognizing the challenges inherent in Mexican wolf recovery, the Recovery Plan recommends

progress evaluations at five and ten years into plan implementation to ensure the recovery strategy

and actions are effective (Service 2022, pg. 27-28). For the five-year evaluation, the Recovery Plan

provides the following demographic and genetic benchmarks:

• 145 wolves in the United States and 100 wolves in Mexico; and

• a sufficient number of wolves have been released or translocated to result in 9 released

animals surviving to breeding age in the United States, and 25 released animals surviving to

breeding age in Mexico.

We will conduct the five-year evaluation in 2023 and 2024, using data through 2022, inclusive of

the 2022 year-end annual population count. Because we will conduct a portion of the 2022 annual

population count in early 2023, we will complete the evaluation six years after finalization of the

Recovery Plan. As of this annual report, the minimum population is 242 Mexican wolves and 13

released or translocated wolves have survived to breeding age to count toward the genetic recovery

criteria. Also as of this annual report, the estimated population in Mexico is 20 Mexican wolves and

nine released or translocated wolves have survived to breeding age to count toward the genetic

recovery criteria.

8

3. SUMMARY OF LITIGATION

Plaintiffs: Center for Biological Diversity; Defenders of Wildlife

Defendants: Secretary of the Interior; US Fish and Wildlife Service

Intervenors: State of Arizona (Defendant)

Allegation: (APA) Violations of NEPA in revising the 10(j) Rule and issuance of associated 10(a)(1)(A)

permit

Date NOI Filed: No NOI Filed on alleged APA violations; 1/16/15 NOI pertaining to 10(a)(1)(A)

permit

Date Complaint Filed: 1/16/15; amended complaint filed 3/23/15

Case Number/Court: 4:15-cv-00019-LAB (D. Ariz.)

Status: The Court entered Judgement in accordance with its 3/ 31/18 Order remanding the 10(j)

Rule. On 4/28/21, the Court granted Plaintiff’s motion to modify the deadline for completion of the

remand stating the Service shall issue a final, revised 10(j) rule by July 1, 2022. A final, revised

10(j) rule was published in the Federal Register on July 1, 2022.

Plaintiffs: Cen

ter

for

Biolo

gical Div

ersity;

WildE

arth

Guardians

Defendants: Secretary of the Interior; US Fish and Wildlife Service

Allegation: APA Violations, NEPA Violations and ESA violations in revising the 10(j) Rule and

issuance of associated 10(a)(1)(A) permit

Date NOI Filed: WildEarth Guardians 7/1/22 NOI; CBD 8/5/22 NOI, No NOI Filed on alleged

APA or NEPA violations.

Date Complaints Filed: 7/12/22 CBD filed its complaint, amended in October 2022 to add ESA

claims; 10/3/22 WEG Complaint;

Case Numbers: No. CV-22-00303-TUC-JAS No. CV-22-00453-TUC-JAS 4:15-cv-00019-LAB (D.

Ariz.)

Status: Court consolidated the two cases on 10/30/22. The United States has answered both

complaints. On January 19, 2023, the Court issued a scheduling order setting forth the schedule

for the case.

Plaintiffs: AZ and NM Coalition of Counties for Stable Economic Growth et al (18 plaintiffs)

Allegation: Violations of APA, NEPA, Regulatory Flex Act. E.O. 12898 in implementing the Record of

Decision/FEIS and 2015 10(j) Rule

Defendants: US Fish and Wildlife Service; Secretary of the Interior; Dan Ashe; Benjamin Tuggle

Intervenors: None

Date NOI Filed: No NOI filed

Date Complaint Filed: 2/12/15

Case Number/Court: 4:15-cv-00179-FRZ (D. Ariz.)

Status: Consolidated with District of Arizona case 4:15-cv-00019-JGZ

Plaintiffs: Wild Earth Guardians; New Mexico Wilderness Alliance; Friends of Animals

Defendants: Director of the US Fish and Wildlife Service; Secretary of the Interior

9

Intervenors: None

Allegation: Violation of ESA for not considering essential status for Mexican wolves; Violation of

NEPA for not assessing revisions to final rule

Date NOI Filed: 3/24/15

Date Complaint Filed: 7/2/15

Case Number/Court: 4:15-cv-00285-JGZ (D. Ariz.)

Status: Consolidated with District of Arizona case 4:15-cv-00019-JGZ

Plaintiffs: Safari Club International

Defendants: Secretary of the Interior; US Fish and Wildlife Service

Intervenors: Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife (Defendants)

Allegation: Violations of ESA, APA, and NEPA promulgating the 2015 10(j) Rule and FEIS/ROD

Date NOI Filed: 8/3/15

Date Complaint Filed: 10/16/15

Case Number/Court: 4:16-cv-00094-JGZ (D. Ariz.)

Status: The Court entered Judgement in accordance with its 3/31/18 Order remanding the

10(j) Rule. On 4/28/21, the Court granted Plaintiff’s motion to modify the deadline for

completion of the remand stating the Service shall issue a final, revised 10(j) rule by July 1,

2022. A final, revised 10(j) rule was published in the Federal Register on July 1, 2022.

Plaintiffs: Cen

ter

for

Biol

o

gical

Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, the Endangered Wolf Center,

David R. Parsons, the Wolf Conservation Center, WildEarth Guardians, Western Watersheds

Defendants: Secretary of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Amy Lueders

Intervenors: New Mexico Department of Game and Fish

Allegation: Violations of ESA and APA regarding the adequacy of the 2017 Mexican wolf

Recovery Plan

Date NOI Filed: 11/29/17

Date Complaint Filed: 1/30/18

Case Number: Ninth Circuit, Nos. 22-15029 & 22-15091 (appeals of 4:18-cv-00047-BGM

and 4:18-cv-00048-JGZ (D. Ariz.)

Status: District Court of Arizona issued 10/14/21 Order remanding the recovery plan to the

Service stating the Service shall produce a draft recovery plan within six months that includes

site-specific management activities and a final plan six months thereafter. The Plaintiffs’

appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals; the United States did not appeal. A draft

revised recovery plan was published in January 2022 and a final revised recovery plan was

published in September 2022. The U.S. Department of Justice filed a motion to dismiss this case

on 11/18/22. The motion to dismiss was dismissed without prejudice to allow the Ninth Circuit

panel to address it when the panel addresses the full case. Oral argument is scheduled for June

5, 2023, in San Francisco.

10

4. MEXICAN WOLF EXPERIMENTAL POPULATION AREA MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that guides the reintroduction and management of the

Mexican wolf population in the MWEPA was revised in 2019 to address the provisions of the

revised 2015 10(j) Rule and 2017 Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, First Revision. Signatories of this

MOU included the Arizona Game and Fish Department, Bureau of Land Management, National

Park Service, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, US Department of Agriculture-Forest

Service, US Department of Agriculture-Wildlife Services, White Mountain Apache Tribe, and the

Service, as well as the cooperating counties of Gila, Graham, Greenlee, and Navajo in Arizona,

Catron County and Sierra County in New Mexico, and the Eastern Arizona Counties Organization

(EACO). A copy of this MOU can be found at https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-

wolf/library.

Each year the IFT produces an Annual Report, detailing Mexican wolf field activities (e.g.,

population status, reproduction, mortalities, releases/translocations, dispersal, depredations, etc.) in

the MWEPA. The 2022 report is included as PART B of this document. Mexican Wolf Recovery

Program Quarterly Updates are available at https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-

wolf/library or you may sign up to receive them electronically by visiting https://www.azgfd.com/

and clicking on the subscribe button at the bottom of the page. Additional information about the

management of Mexican wolves can be found on the Service’s web page at:

https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-wolf or AZGFD’s web page at:

https://www.azgfd.com/wildlife-conservation/conservation-and-endangered-species-

programs/mexican-wolf-management/.

11

5. COOPERATIVE AGREEMENTS

In 2022, the Service funded cooperative or grant agreements with AZGFD, The Cincinnati Zoo,

Turner Endangered Species Fund (TESF), University of Idaho, University of New Mexico, and

WMAT. These agreements convey funding for the monitoring and management of captive and

wild Mexican wolves (AZGFD, Cincinnati Zoo, TESF, and WMAT), administration and facilitation

of recovery planning and implementation efforts (Mexican Wolf Fund―when funded), and

genetic analysis and preservation of biomaterials (University of Idaho and University of New

Mexico). The Service also provides funding to AZGFD and NMDGF for Mexican wolf recovery

through Section 6 of the Act, which requires 25 percent percent matching funds from each state.

Cooperator

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Mexican Wolf Project

Funds Provided in 2022

AZGFD

$ 240,000

Cincinnati Zoo

$ 40,000

TESF

$ 40,000

University of Idaho

$ 20,000

University of New Mexico

$ 15,000

White Mountain Apache Tribe

$ 375,000

In addition to the above agreements, the Service also provided funding for several

miscellaneous contracts for veterinary, helicopter, mule packing, and other services. For more

information on Program costs to date visit https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-

wolf/library.

12

6. LIVESTOCK CONFLICT COMPENSATION PROGRAMS

There are currently two programs from which livestock producers can seek compensation for

confirmed livestock losses due to predation by Mexican wolves, 1) the Livestock Indemnity

Program authorized by the 2018 Farm Bill and administered by the U.S. Department of

Agriculture’s Farm Service Agency, and 2) the Wolf Livestock Loss Demonstration Grants

authorized by the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-11) and awarded

by the Service through a competitive process to qualifying States and Tribes.

Livestock Indemnity Program

The Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) compensates livestock producers for losses in excess of

normal mortality that are due to adverse weather or attacks by animals reintroduced to the

wild by the Federal Government. LIP compensation payments are equal to 75 percent of the

(national) average fair market value of the livestock. For more information see

https://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/disaster-assistance-program/livestock-

indemnity/index.

Wolf-Livestock Loss Demonstration

Project Grants

The Service provides approximately $1,000,000 annually through a competitive process to

eligible states and tribes to (1) assist livestock producers in undertaking proactive, non-lethal

activities to reduce the risk of livestock loss due to predation by wolves, and (2) compensation

to livestock producers for livestock losses due to wolf predation. P.L. 111-11 states that funding

made available should be allocated equally between the two grant purposes (compensation

and prevention), and that the Federal share of the cost does not exceed 50 percent (requires a

50 percent non-Federal match).

The Wolf-Livestock Loss Demonstration Project Grants (WLDG) are applied for by AZGFD and

New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) in Arizona and New Mexico, respectively. The

Arizona Livestock Loss Board administers the funds received by AZGFD; the Mexican

Wolf/Livestock Council assisted in administering the funds received by NMDA in 2022. The

County Livestock Loss Authority will begin administering the funds received by NMDA in 2023.

For more information on the Arizona Livestock Loss Board please visit https://live-

azlivestocklossboard.pantheonsite.io/.

13

The following

tables reflect annual WLDG amounts and disbursement of funds for associated activities.

Note that these expenditures required at least a 1:1 non-Federal match.

Year

Direct Compensation for

Livestock Lost - Arizona

Direct Compensation for

Livestock Lost – New Mexico

Total

2011 $5,400 $12,781 $18,181

2012

$7,550

$15,050

$22,600

2013

$14,581

$13,013

$27,594

2014

$21,100

$42,624

$63,724

2015

$33,070

$77,133.90

$110,203.90

2016

$15,785

$58,041.18

$73,826.18

2017

$29,880

$29,942.50

$59,822.5

2018 $17,850 $92,573.38 $110,423.38

2019

$99,312.37

$185,797.46

$285,109.83

2020 $68,306.10 $105,892.00 $174,198.10

2021 $98,016.32 $80,931.00 $178,947.32

2022 $140,014.20 $62,302 $202,316.20

Year

Arizona

Wolf/Livestock

Conflict Prevention

Arizona

Wolf/Livestock

Pay for

Presence

New Mexico

Wolf/Livestock

Conflict Prevention

New Mexico

Wolf/Livestock

Pay for Presence

Total

2011

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

2012

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

2013

N/A

$38,000

N/A

$47,500

$85,500

2014

N/A

$38,000

N/A

$47,500

$85,500

2015

N/A

$51,000

N/A

$32,300

$83,300

2016

N/A $48,000

N/A

$57,000

$105,000

2017

$10,000 $50,000

N/A

$57,000

$117,000

2018

$21,000 $60,000

N/A

$57,000

$138,000

2019

$156,043.80

N/A

N/A

$57,000

$213,043.80

2020

$90,000.20 N/A

N/A

$57,000

$147,000.20

2021

$94,500

N/A

N/A

N/A

$94,500

2022

$77,500

N/A

N/A

N/A

$77,500

14

7. LITERATURE CITED

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1982, Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan 1982, US Fish and Wildlife

Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998, Final Rule. Establishment of a Nonessential Experimental

Population of the Mexican Gray Wolf in Arizona and New Mexico, 63 Federal Register

1752-1772.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2013, Proposed Rule. Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) From the

List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Maintaining Protections for the Mexican

Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) by Listing It as Endangered, 78 Federal Register 35664-35719.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2014. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Revision

to the Regulations for the Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Wolf. 79

Federal Register 70154-70155.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015. Revision to the Regulations for the Nonessential Experimental

Population of the Mexican Wolf. 80 Federal Register 2512-2567.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015. Endangered Status for the Mexican Wolf. 80 Federal Register

2488-2512.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, First Revision, US Fish and

Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2022. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, Second Revision, US Fish and

Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

15

PART B: REINTRODUCTION

MEXICAN WOLF EXPERIMENTAL POPULATION AREA INTERAGENCY FIELD TEAM ANNUAL

REPORT

Reporting period:

January

1

-

December

31,

2022

Prepared by:

Arizona Game and Fish Department, New Mexico Department of Game and

Fish, U.S. Department of Agriculture - Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service - Wildlife Services, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service,

and White Mountain Apache Tribe.

Participating Agencies:

Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD)

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF)

USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services USDA-WS)

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service)

U.S. Forest Service (USFS)

White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT)

16

1. KEY DEVELOPMENTS

• A minimum of 242 Mexican wolves and 32 breeding pairs were documented in the Mexican

Wolf Experimental Population Area (MWEPA) at the end of 2022.

• Eleven new packs and 1 new pair were documented at the end of 2022.

• Pup survival increased to 68 percent in 2022 (compared to 39 percent in 2021), with 82

pups surviving until the end of the year. The pup survival rate in 2022 was higher than the

previous ten-year (2012-2021) average of 62 percent.

• Eleven genetically diverse wolf pups were fostered from captive facilities across the United

States into five wild wolf dens in Arizona and New Mexico. By the end of 2022, thirteen

fostered wolves (from all years) were radio-collared and known to be alive. From 2016 to

the end of 2022, seven fostered wolves had been documented producing pups and a

minimum of eleven different litters had been produced by foster wolves.

• A high adult survival rate (0.92) combined with the number of pups that survived to

December 31, resulted in a high population growth (23 percent in 2022). Thus, the

population exceeded the management objective for 2022 of a 10 percent increase in the

minimum population count and/or the addition of at least two breeding pairs.

The high

number of pups recruited in the last two years, 56 and 82 in 2021 and 2022, respectively,

contributed to the high population growth.

A member of the field team brings in a sedated wolf during the year-end population count. Credit:

Mexican Wolf Interagency Field Team.

17

• In 2022, the overall (inclusive of all age classes) survival rate (0.89) was higher than the to

the previous 10- year (2012-2021) period (0.73).

At the end of 2022, thirteen released wolves counted toward the genetic criterion (AM1471,

AF1578, F1692, AM1693, M1710, F1712, F1866, M1888, F1889, F1890, M1953,

F2503, M2545). Seven of these thirteen fostered wolves produced pups in 2022 (AM1471,

AF1578, AM1693, AF1712, F1866, AF1890, AF2503).

The 2022 confirmed killed cattle rate of approximately 56.20 depredations/100 wolves

was slightly lower than the previous 10-year (2012-2021) recovery program mean of

60.37 confirmed killed cattle per 100 wolves. Therefore, meeting the program goal of

maintaining the depredation rate at or below the previous 10-year recovery program

mean. The 2022 depredation rate decreased by 10 percent from 2021.

•

•

An un

collared Mexican wolf seen on a trail camera. Credit: Mexican Wolf Interagency Field Team.

18

2. INTRODUCTION

The reintroduction, monitoring and management of Mexican wolves in the MWEPA is part of a

larger recovery program that is intended to reestablish the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) within

its historical range in the United States and Mexico. The first releases of Mexican wolves occurred in

March 1998 on the Alpine and Clifton Ranger Districts of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest,

Arizona. In 2022, the wild population minimum count increased to 242 wolves; this report

summarizes the results of Mexican Wolf IFT activities during 2022. The objective of this report is to

document progress towards recovery goals set out in the 2022 Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan,

Second Revision (Recovery Plan) for the United States population.

More information on population metrics can be found at: https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-

mexican-wolf/library.

a. Background

The Recovery Plan establishes several important metrics to gage relative progress towards recovery.

First, the recovery criteria call for an average of at least 320 wolves over eight years in the United

States population. Thus, a growing population is an important measure of success. The population

viability model Miller (2017) used to help determine recovery criteria show scenarios with mean

adult mortality rates less than 25 percent, combined with mean sub-adult mortality rates less than 33

percent and mean pup mortality (for radio-marked pups greater than four months old) less than 13

percent resulted in an increasing population that will meet the population abundance recovery

criteria, under certain management regimes. In particular, Miller (2017) found that growth rates and

recovery were sensitive to small changes in adult mortality. Thus, adult mortality will be an important

metric for evaluation of the program. On a favorable note, the documented annual mortality in

2022 was the lowest since 2017 and was substantially lower than the documented annual mortality

totals in 2021 and 2020. The recovery criteria also call for 22 wolves released from captivity to

survive for one (sub-adults and adults) to two (pups) years following release. This recovery criterion

allows for the incorporation of under-represented genes from captivity into the wild population. Thus,

the survival of animals released from captivity into the population will need to continually be

monitored.

Evaluations will be conducted five and ten years from the publishing of the 2017 Recovery Plan, First

Revision to determine the progress of the Mexican wolf population toward recovery goals. The five-

and ten- year evaluations will assess the status of the United States and Mexico populations toward

recovery. The interim abundance target at the end of 2022 is 145 wolves in the United States and

100 wolves in Mexico. The interim release and translocation target at the end of 2022 is nine

released wolves surviving to breeding age in the United States and 25 released or translocated

wolves surviving to breeding age in Mexico. The interim abundance target in 2027 is 210 wolves in

the United States and 167 wolves in Mexico. The interim release target in 2027 is 16 wolves

released from captivity surviving to breeding age in the United States and 37 released or

translocated wolves surviving to breeding age in Mexico. These evaluations will determine if the

recovery strategy is proving effective and feasible or needs to be revised.

19

Management of wolves

in the MWEPA is conducted in accordance with an experimental population

Final Rule (Service 2022; 2022 10(j) Rule). This rule designates the reintroduced population as

experimental and nonessential and establishes the MWEPA within historical range south of Interstate

40 to the United States-Mexico border in Arizona and New Mexico, inclusive of three management

areas (Zone 1, 2, and 3; Figure 1). Mexican wolves can occupy any portion of the MWEPA (Zones

1-3), can be released into Zone 1 (or in accordance with tribal or private land agreements in Zone

2), and/or translocated into Zones 1 and 2 (note: fostering―considered a release―may be

conducted in Zone 1 and on Federal lands in Zone 2). Zone 1 includes all the Apache-Sitgreaves

and Gila National Forests; the Payson, Pleasant Valley and Tonto Basin Ranger Districts of the

Tonto National Forest; and the Magdalena Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest. In 2000,

the WMAT agreed to allow free-ranging Mexican wolves to inhabit the Fort Apache Indian

Reservation (FAIR). The FAIR is in east-central Arizona and provides 2,440 mi

2

(6,319 km

2

) of area

that wolves may occupy. See the Final Rule (Service 2022; 2022 10(j) Rule) for more information.

Figure 1: The Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area (MWEPA) and Zones 1-3 in Arizona and

New Mexico as described in the Final Rule.

20

Wolf age and sex abbreviations used in this document:

A = alpha/breeder (wolf that has successfully bred and produced/sired at least one pup)

M = adult male (24 months or older)

F = adult female (24 months or older)

m = subadult male (younger than 24 months)

f = subadult female (younger than 24 months)

mp = male pup (born in the most recent spring)

fp = female pup (born in the most recent spring)

Specific information regarding wolves on the FAIR and the San Carlos Apache Reservation (SCAR) is

not included in this report in accordance with tribal agreements. However, wolves occurring on the

FAIR and SCAR are included in total counts for depredations and population metrics.

3. POPULATION STATUS

a. Definitions

Breeding pair: a pack that consists of an adult male and female and at least one pup of the

year surviving through December 31.

Wolf pack: two or more wolves that maintain an established territory. In the event that one of

the wolves dies, the remaining wolf, regardless of pack size, usually retains the pack name.

New pair: a male and female wolf, traveling together for at least one month, that are likely to

form a new pack.

b. Monitoring

Techniques

The year-end minimum population count (population or population count) is derived from

information gathered through a variety of methods deployed annually from November 1

through the year-end helicopter operation. The IFT continued to employ comprehensive efforts

initiated in 2006 to make the 2022 year-end population count accurate, consistent, and

repeatable. Management actions implemented to document Mexican wolves included: surveys

and trapping for uncollared wolves, greater coordination and investigation of wolf sightings

provided through the public and other agency sources, deployment of remote trail cameras,

cameras at supplementary and diversionary food caches, and howling surveys in areas of

suspected uncollared wolves.

Wolf sign (e.g., tracks, scats) was documented by driving roads and hiking canyons, trails, or

other areas closed to motor vehicles. Confirmation of uncollared wolves was achieved via visual

observation, remote cameras, howling, scats, and tracks. Ground survey efforts for suspected

packs having no collared members were documented using global positioning system (GPS) and

geographical information systems (GIS) software and hardware. GPS locations were recorded

and downloaded into GIS software for analysis and mapping.

21

In January an

d February 2023, aircraft were used to document wolves for the 2022 year-end

population count and to capture wolves to affix radio collars. Including January and February count

data in the December 31 population count (and in this 2022 annual report) is appropriate and

consistent with previous years’ annual counts, because wolves alive in these months were also alive in

the preceding December (i.e., whelping only occurs in spring, and any wolf added to the population

via initial release or translocation after December 31 and before the end of the survey are not

counted in the year-end population count). During the year-end count, fixed-wing aircraft were

used to locate wolves and assess the potential for darting wolves from the helicopter. A helicopter

was used to obtain a visual count of uncollared wolves associated with collared wolves in all areas

and to capture priority animals (e.g., uncollared wolves, injured wolves, or wolves with failed or old

collars) where the terrain and land ownership allowed.

As part of the 2022 year-end population count, the IFT coordinated with and surveyed members of

the local public to identify possible wolf sightings. Ranchers, private landowners, wildlife managers,

USFS personnel, and other agency cooperators were contacted to increase wolf sighting data for

the database. All such sightings were reviewed to determine those that most likely represented

unknown wolves or wolf packs for purposes of completing the population count.

Documentation of wolves or wolf sign, obtained through the above methods, was also used to guide

efforts to trap uncollared single wolves or groups of wolves. The objective is to have at least one

member (preferably two) of each pack collared. These various methods also allowed the IFT to

count uncollared wolves not associated with collared wolves.

Two wolves from the Whitewater Canyon pack seen on a trial camera. Credit: Mexican Wolf Interagency

Field Team.

22

c. Minimum

Population

Count

At th

e end of 2022, the population count was 242 wolves, which was a 23 percent increase from the

previous year’s population (n=196; Figure 2). Pups comprised 34 percent of this population. Thirty-two

packs were considered breeding pairs in 2022, compared to twenty-five in 2021.

At end of 2022, the functioning collared population consisted of 109 radio-collared wolves among 56

packs, and eight single wolves, which was an overall increase from 2021 (Table 5). A total of 133

uncollared or failed collared wolves were documented at the end of 2022 (note: all the uncollared wolves

captured during the January and February 2023 helicopter operation were included as uncollared animals

associated with known packs above; Table 5).

Sixteen uncollared wolves were documented in 2022 (Figure 3) that were not associated with known

packs. Searches for uncollared wolves occurred throughout the calendar year; however, only uncollared

wolves documented between November and the end of the annual helicopter count and capture

operations are included in the population count for the year.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

No. of Wolves

Minimum Population

Figure 2: Mexican wolf minimum population counts from 1998 through 2022 in Arizona and New Mexico.

23

Figure 3: Areas searched for uncollared wolf sign within the Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area.

Areas where the uncollared wolves documented contributed to the year’s total population count are

indicated as uncollared wolves documented. Overlap of polygons with tribal lands do not necessarily

indicate sign search conducted on tribal land. Five initial release sites (dens for fostering efforts) were used

during 2022 in Arizona and New Mexico.

d. Reproduction

In 2022, 36 packs exhibited denning behavior, which included 13 packs in Arizona and 23 packs in

New Mexico. Of the 36 packs, 32 of those were considered breeding pairs at the end of the year.

The IFT also fostered a total of 11 captive-born pups into dens of five wild packs in Arizona and

New Mexico. A maximum of 121 pups were documented with a minimum of 82 surviving in the wild

until year-end in Arizona (n = 32) and New Mexico (n = 50), which showed that 68 percent of the

pups documented in early counts survived until the end of the year (Figure 4, Table 5).

24

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

No. of Wolves

Minimum Population Reproduction Pup Recruitment

Figure 4: Mexican wolf minimum population estimate, reproduction (maximum number of pups documented),

and recruitment (number of pups surviving at years end) documented in Arizona and New Mexico, 1998-

2022.

e. Captures

In 2022, 47 wolves were captured a total of 49 times. Thirty wolves were captured, collared for the

first time, processed, and released on site for routine population monitoring purposes. Nine wolves

were captured, re-collared, processed, and released on site, or simply released on site with the

current collar. One wolf was translocated, and three wolves were removed to captivity. Three

wolves were captured by the IFT for veterinary care, two were released after treatment, and one

wolf was humanely euthanized at the veterinary hospital. Three wolves were captured by private

trappers. Two of these wolves were released on site by the IFT. One of these wolves required

veterinary care and was released after treatment.

f. Releases and Translocations

Foster: the transfer of offspring from their biological parent(s) and placement with surrogate

parent(s). If the offspring were in captivity at the time of the transfer, this is also considered an Initial

Release (see definition below). If the offspring were in the wild at the time of their transfer this is also

considered a Translocation (see definition below).

Initial Release: the release of Mexican wolves to the wild within Zone 1 (Figure 1), or in accordance

with tribal or private land agreements in Zone 2 (Figure 1), that have never been in the wild, or

releasing pups that have never been in the wild and are less than five months old within Zones 1 or 2.

The initial release of pups less than five months old into Zone 2 allows for the fostering of pups from

the captive population into the wild, as well as enables translocation-eligible adults to be re-

released in Zone 2 with pups born in captivity (see 2022 10(j) Rule at

https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-wolf/library.

A pile of captive-born and wild-born Mexican pups mixed together during 2022 fostering efforts. Credit:

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

25

Translocations: the release of Mexican wolves into the wild that have previously been in the wild. In

the MWEPA translocations will occur only in Zones 1 and 2 (Figure 1; see 2022 10(j) Rule at https://

www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-wolf/library.

Supplemental Food Cache: road-killed native prey carcasses or carnivore logs provided to wolves to

assist a pack or remnant of a pack when extenuating circumstances reduce their own ability to do so

(e.g., one animal raising young, or just after initial releases and translocations (including fostering)).

In 2022, eleven wolves were initially released (all 11 were fostered pups; Table 1, Figure 3, Figure

5) into five packs (Buzzard Peak, Dark Canyon, Iron Creek, Rocky Prairie, Whitewater Canyon).

These captive-born pups came from five SSP facilities including: Chicago Zoological Park

(Brookfield Zoo), El Paso Zoo, Wolf Conservation Center, Sevilleta Wolf Management Facility, and

the Southwest Wildlife Conservation Center. These foster events occurred in April and May 2022.

Additionally, one wolf was translocated in 2022 (Table 1). Translocations can occur throughout the

year. We supplementally fed packs where foster events occurred. Supplemental food assists the

pack with the nutritional demand of additional pups. Of the 12 wolves that were initially released

or translocated in 2022, three were captured by the IFT, radio collared and known to be alive

during the end of year count (m2590, mp2709, mp2722), and 9 were uncollared and considered

fate unknown (mp2710, fp2717, mp2718, mp2719, mp2723, fp2724, mp2727, fp2728, fp2736)

as the IFT had not been able to capture and collar the pups, nor were they documented as a

mortality. The IFT will continue efforts to document surviving fostered pups in the following years.

26

Table 1: Mexican wolves initially released from captivity or translocated

from the wild in Arizona and New Mexico during January 1 – December

31, 2022.

Wolf pack

Wolf ID

Release site

Release date

Released or translocated

Buzzard Peak

mp2709 Buzzard Peak Den

4/28/2022

Released (fostered)

Buzzard Peak

mp2710 Buzzard Peak Den

4/28/2022

Released (fostered)

Dark Canyon mp2723 Dark Canyon Den 5/12/2022

Released (fostered)

Dark Canyon fp2724 Dark Canyon Den 5/12/2022

Released (fostered)

Iron Creek mp2722 Iron Creek Den

5/12/2022

Released (fostered)

Iron Creek fp2736 Iron Creek Den

5/12/2022

Released (fostered)

Rocky Prairie

mp2727

Rocky Prairie Den

5/6/2022

Released (fostered)

Rocky Prairie fp2728 Rocky Prairie Den

5/6/2022

Released (fostered)

Whitewater

Canyon

fp2717 Whitewater

Canyon Den

5/6/2022 Released (fostered)

Whitewater

Canyon

mp2718 Whitewater

Canyon Den

5/6/2022 Released (fostered)

Whitewater

Canyon

mp2719 Whitewater

Canyon Den

5/6/2022 Released (fostered)

Single

mp2590 Gila Flats 3/18/2022

Translocated

27

Figur

e 5: Mexican wolf minimum population estimates and associated releases and translocations

including: initial releases (wolves released with no wild experience), translocations (wolves re-released

from captivity back into the wild, and wolves in the wild that were captured, moved, and re-released in a

different location for management purposes such as but not limited to boundary issues and conflicts with

livestock).

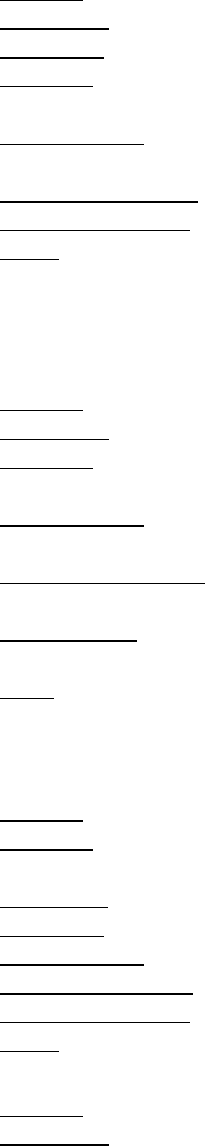

g. Home Ranges and Movements

Home ranges were calculated using ≥20 individual locations on a pack, pair, or single wolf

exhibiting territorial behavior over a period of greater than six months. Due to the large volume of

deployed GPS collars, individual wolves were selected to represent a pack’s home range territory

(Kittle et al. 2015). When possible, breeders were selected to represent the territorial behavior of

the pack with preference given to the breeding female. To maximize sample independence, two

locations per animal per day were used in the analysis. After any major pack disturbance that

affected territorial behavior (i.e., death of a breeder), GPS locations were right-censored to avoid

extra territorial movement. Home ranges were not calculated for wolves that displayed dispersal

behavior or exhibited non-territorial behavior during 2022. Individual point selection was

accomplished with program R (R Core Team 2015). Home range polygons were generated using the

95 percent adaptive kernel method (Seaman and Powell 1996) with R and the adehabitatHR

package in conjunction with ArcPro (Calenge 2019, ESRI 2018).

All wolves equipped with functioning radio collars were monitored by standard radio telemetry

opportunistically from the ground and air (White and Garrot 1990). During all or portions of the

year, 117 wolves were equipped with Global Positioning Collars (GPS) collars to provide more

detailed location information and management capability.

Home ranges were calculated for 47 packs or pairs exhibiting territorial behavior in 2022 using

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Minimum Population Releases & Translocations

28

kernel density estimation (Seaman et al. 1999). These home ranges were between 48 square miles

(Sierra Blanca pack) and 1,767 square miles (Manada del Arroyo pack), with an average home

range size of 208 square miles (Figure 6). For additional information regarding home range details

in Arizona and New Mexico please see Appendix A.

Figure 6: Mexican wolf home ranges (95 percent fixed kernel utilization distribution) for 2022 in Arizona

and New Mexico excluding tribal lands. Darker areas indicate overlap between home ranges.

29

h. Dispersals

In 2022, the IFT documented 18 collared wolves that dispersed from their natal packs (i.e., the

pack the wolf was born into or raised by). These dispersing wolves were classified into one of

three categories: 1) dispersed to form a new pack (n = 7); 2) dispersed into an existing pack (n

= 3); or 3) were still single wolves at the end of the year (n = 8).

i. Occupied Range

Occupied wolf range was calculated based on the following criteria: (1) a ten-mile radius

around all aerial locations or GPS locations of radio monitored wolves over the past year; (2)

a ten-mile radius around all uncollared wolf locations and wolf sign over the past year; and (3)

in accordance with the 2022 10(j) Rule, occupied range is calculated within the 10(j) boundary

of the MWEPA and does not include tribal lands or areas in management Zone 3.

Under this definition, Mexican wolves occupied 29,663 square miles of the MWEPA during

2022 (Figure 7). In comparison, Mexican wolves occupied 26,877 square miles during 2021.

The Mexican wolf occupied range increased by 10 percent from 2021. For additional

information on areas utilized by Mexican wolves in 2022, please see Appendix B.

Figure 7: Mexican wolf occupied range in Arizona and New Mexico during 2022.

30

i. Mortality and Removal

s

Wolf mortalities were detected via ground telemetry, GPS locations, and public reports. Mortality

signals from radio collars were investigated within approximately 24 hours of detection to determine

the status of the wolf. Carcasses were investigated by law enforcement personnel from the lead

agencies and necropsies were conducted to determine cause of death (Table 2). The IFT has

documented 253 wolf mortalities since 1998, 12 of which occurred in 2022 (Tables 2 and 3, Figure

8). The annual mortality total for 2022 was substantially lower than 2021 (25 mortalities) and 2020

(29 mortalities) and was the lowest annual total of documented Mexican wolf mortalities since 2017

(12 mortalities) when the Mexican wolf population was significantly smaller (minimum of 114 wolves).

Causes of death were classified into six categories including: 1) illegal mortality; 2) vehicle collision;

3) natural; 4) other; 5) unknown; and 6) pending necropsy. Seven of the 12 (59 percent)

documented wolf mortalities were considered illegal and accounted for the majority of deaths. Three

of the 12 (25 percent) documented wolf mortalities were caused by a vehicle collision. One of the

12 (8 percent) documented wolf mortalities died from natural causes (e.g., starvation, exposure,

interspecific competition, intraspecific competition). Cause of death could not be determined for one

of the 12 (8 percent) documented wolf mortalities. In total, 10 (83 percent) of the documented

mortalities are considered human-caused (includes illegal mortality and vehicle collision). All causes

of death should be considered minimum estimates of mortality, as uncollared wolves (of any age,

including those with failed collars) may die without those mortalities being documented.

31

Table 2: Wild Mexican wolf mortalities documented in Arizona and New

Mexico, 1998-2022.

Year

Illegal

mortality

a

Vehicle

collision

Natural

b

Other

c

Unknown

Awaiting

necropsy

Annual

total

1998 4 0 0 1 0 0 5

1999 0 1 2 0 0 0 3

2000 2 2 1 0 0 0 5

2001 4 1 2 1 1 0 9

2002 3 0 0 0 0 0 3

2003 7 4 0 0 1 0 12

2004 1 1 1 0 0 0 3

2005 3 0 0 0 1 0 4

2006 1 1 1 1 2 0 6

2007 2 0 1 0 1 0 4

2008 7 2 2 0 2 0 13

2009 4 0 4 0 0 0 8

2010 5 0 1 0 0 0 6

2011 3 2 3 0 0 0 8

2012 4 0 0 0 0 0 4

2013 5 0 0 2 0 0 7

2014 7 1 3 0 0 0 11

2015 8 0 3 0 2 0 13

2016 7 2 1 2 2 0 14

2017 6 1 4 0 1 0 12

2018 13 2 3 0 3 0 21

2019 9 1 1 2 2 0 15

2020 14 6 0 4 6 0 30

2021 12 5 4 3 1 0 25

2022 7 3 1 0 1 0 12

Total 138 35 38 16 26 0 253

a

Illegal mortality causes of death may include but are not limited to known or suspected illegal shooting with a

firearm or arrow, and illegal trap related mortalities by the public following necropsy.

b

Natural causes of death may include, but are not limited to predation, starvation, interspecific strife, lightening, and

disease.

c

Other causes of death include capture-related mortalities. legal shootings and legal trap related mortalities

by the public.

32

Wolves not

located or otherwise documented alive for three or more months are considered missing or

“fate unknown.” These wolves may have died, dispersed, or have a malfunctioned radio collar. Two

wolves last located in Arizona (2540, 2602) and four wolves last located in New Mexico (1158, 1285,

1834, 2635) were designated fate unknown (e.g., not observed via sightings, remote cameras, or radio

telemetry for >3 months during portions of 2022).

Table 3: Mexican wolf mortalities documented in Arizona and New

Mexico during January 1-December 31, 2022.

Wolf ID Pack

Age

(years)

Date found Cause of death

m2520

Single

1

1/1/2022

Illegal

F1791

Prime Canyon

3

1/21/2022

Unknown

M1290

Hoodoo

10

3/30/2022

Vehicle collision

m2594

Lava

1

7/13/2022

Illegal

F2751

New Pack AZ

2

7/17/2022

Illegal

m2605

Hoodoo

1

7/28/2022

Natural

F1837

Beaver Point

3

7/29/2022

Illegal

M1693

Seco Creek

4

10/7/2022

Illegal

m2761

Uncollared wolf

1

10/26/2022

Vehicle collision

mp2699

Uncollared wolf

<1

11/5/2022

Vehicle collision

F1684

Whitewater Canyon

5

12/9/2022

Illegal

F1701

Owl Canyon

4

12/20/2022

Illegal

For wolves equipped with radio collars, mortality, missing, and removal rates were calculated using

methods presented in Heisey and Fuller (1985). Missing animals were censored at the date of the last

signal/location of a functioning collar and classified as likely alive or dead based on the totality of

the information associated with the failure (e.g., do we have subsequent photos of the animal, did the

collar malfunction suddenly or fail in a predictable manner, etc.).

Management removals can have an effect equivalent to mortalities on the population of Mexican

wolves (Paquet et al. 2001). Thus, yearly cause-specific removal rates were calculated for wolves

equipped with radio collars. Wolves are removed from the population for four primary causes: 1)

livestock depredations; 2) nuisance to humans; 3) wolves are outside the boundary (e.g., north of I-40

or requested removal from tribal lands (these wolves are generally translocated within the U.S. or

Mexico)); and 4) other (e.g., pair with other wolves, veterinary treatment, move a wolf to a more

appropriate area without any of the other causes occurring first). Each time a wolf was moved, it was

considered a removal, regardless of the animal’s status later in the year (e.g., if the wolf was

translocated or held in captivity). Fourteen wolves equipped with functioning radio collars were

considered removed (n = 3), dead (n = 8), or missing (n = 3). Uncollared wolves and individuals with

33

failed collars (documen

ted dead n = 4; removed n = 1) were not included in the analysis of

management removals.

An overall failure rate of wolves was calculated by combining mortality, missing (only those wolves

that went missing under questionable scenarios), and removal rates to represent the overall yearly

rate of wolves affected (i.e., dead, missing, or managed) in a given year. Uncollared or failed-

collared wolves that were found dead or removed were not included in the survival analyses because

these wolves were not consistently monitored throughout the year (e.g., animals may die without being

found and the individuals that are found are random occurrences that do not reflect overall

population dynamics). In addition, wolves that died as a result of handling (no wolves with functioning

radio collars died as a result of handling in 2022) were right-censored at the time of their death (e.g.,

radio days were counted until their death, but the death was not counted in survival estimates) in

accordance with standard survival analyses methodology (Heisey and Fuller 1985, Smith et al. 2010).

The overall survival rate was 0.89 with a corresponding failure rate of 0.11. The overall failure rate

was composed of human caused mortality rate (0.07; n = 8), natural mortality rate (0.00; n = 0),

unknown/awaiting necropsy mortality rate (0.00; n = 0), boundary removal rate (0.01; n = 1),

missing wolves’ rate (0.01; n = 1), livestock depredation removal rate (0.00; n = 0), nuisance removal

rate (0.01; n = 1), and other removal rate (0.01; n = 1). Much of the mortality was concentrated on

sub-adult (radio days = 9,825, failures = 5, survival rate = 0.83), and pup (radio days = 1,938,

failures = 1, survival rate = 0.83) components of the population relative to the adults (radio days =

26,455, failures = 6, survival rate = 0.92).

Based on meta-analysis of gray wolf literature, Fuller et al. (2003) identified a 0.34 mortality rate as

the inflection point of wolf populations. Theoretically, wolf populations below a 0.34 mortality rate

would increase naturally, and wolf populations above a 0.34 mortality rate would decrease. The

Mexican wolf population had an overall failure (mortality plus removal plus missing rate) rate of 0.11

in 2022. Following Fuller et al. (2003), our failure rate would predict an increasing population which

was the case in 2022. Further, Miller (2017) found that population growth was particularly sensitive to

adult failure rates, which were lower in our population (0.08) than other components (sub-adults 0.17,

pups 0.17) in 2022. High number of pups recruited in the last two years 56 and 82 in 2021 and

2022, respectively, contributed to the rapid increase of the population in 2022. The number of

management removals has remained low in the recent past with the majority of the population losses

in 2022 being due to human-caused mortalities. The overall failure rate was extremely low 2022

which also contributed to the high growth rates observed in 2022.

34

Figure 8: Mexican wolf minimum population estimates and associated removals and mortalities, 1998-2022.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Minimum Population Mortalities Removals

35

4. CONFLICT

MANAGEMENT

Reports of wolf-caused livestock depredations are investigated and classified by USDA-WS as

confirmed wolf, probable wolf, or determined as not having wolf involvement. A depredation is

defined as a confirmed killing or wounding of lawfully present domestic animals by one or more

Mexican wolves. A depredation incident is defined as the aggregate number of livestock killed or

mortally wounded by an individual wolf or by a single pack of wolves at a single location within a

one-day (24 hr.) period, beginning with the first confirmed kill, as documented in an initial IFT

incident investigation. Depredation investigations of injuries of animals that survive that are confirmed

or probable are not considered depredation incidents. Depredation investigations where an animal

is killed, and the investigator determines the death was probably caused by wolves are also not

considered depredation incidents.

USDA-WS investigated suspected wolf depredations on livestock, including dead and injured

livestock within 24 hours of receiving a report unless rare circumstances prevented arrival within 24

hours. Not all dead livestock were found or found and reported in time to document cause of death.

Accordingly, depredation numbers in this report represent the minimum number of livestock confirmed

by USDA-WS to have been killed by wolves.

a. Depredations

In 2022, investigators confirmed that wolves were responsible for the death of 136 cattle, and one

horse and injuries to 12 cattle and one dog. Additionally, nine cattle were identified as probable

wolf-caused deaths and two cattle were identified as probable wolf-caused injuries (Table 4). In

2022, the total number of confirmed depredation incidents increased by 8 percent from 2021

(Figure 9). Investigations of dead and injured livestock conducted by USDA-WS that were

determined to be from causes other than wolves (i.e., vehicle strike, illness, coyote predation, bear

predation, or unknown cause) are not listed.

Table 4: USDA-WS confirmed and probable wolf depredations by type

of incident and state in 2022.

Confirmed Wolf

Probable Wolf

Killed or died

from injuries

Injured

Killed or died

from injuries

Injured

Arizona

49

8

3

2

New Mexico

88

5

6

0

Total

137

13

9

2

36

Figure 9: Total number of confirmed depredation incidents (animal killed or died from injuries) by state

2017-2022.

From 2012 to 2021 (10-year average), the mean number of cattle confirmed killed by wolves per

year is 77.4 which extrapolates to 60.37 cattle killed per year per 100 Mexican wolves (Figure

10). The mean of cattle killed per year per 100 wolves is useful for comparison purposes in 2022.

The depredation rate for 2022 extrapolates to 56.20 confirmed cattle killed per 100 wolves using

the number of confirmed killed cattle compared to the final population count. Furthermore, the 2022

rate is slightly below the previous 10-year average (2012 to 2021) mean of 60.37 confirmed

killed cattle/100 wolves/year, and the 2022 depredation rate decreased by 10 percent from

2021.

15

33

55 55

48

4919

73

122

105

79

88

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

No. of Confirmed Depredation Incidents

Years

Arizona New Mexico

37

Figure 10: Mean number of cattle killed per year per 100 Mexican wolves, 2009-2022.

b. Wolf-Human

Conflict

Wolf-human conflict incidents are categorized as: imminent threat to humans, potential threat to

humans, or nuisance incidents in which a report is taken of unacceptable wolf behavior or a wolf

sighting in an unacceptable area, such as near a residence, but not posing an imminent or potential

threat to humans. Though wolf attacks on humans are very rare in North America, we recognize there is

potential for wolves, as with all large predators, to pose a risk to human safety. For this reason and to

build social tolerance of wolves, every effort is made to investigate such reports in a timely manner,

determine what wolf/wolves were involved in the incident and implement management efforts to avert

or resolve credible reports of wolf-human conflict. Some wolf-human conflict reports are determined to

involve animals that are not wolves, such as dogs or coyotes. Other reports are classified as unknown if

it cannot be determined that wolves were present or responsible.

In 2022, the IFT fielded 34 wolf-human conflict reports. Of the 34 reports, the IFT determined 21

reports (Figures 11 and 12) involved or may have involved Mexican wolves, 12 reports involved

species other than wolves (domestic dogs, coyotes, etc.) and one report the IFT was unable to determine

if wolves were involved or not. Of the reports that involved or may have involved wolves, all 21 were

determined to be nuisance incidents not posing an imminent or potential threat to humans.

Following a report of wolf-human conflict, IFT members used on-site investigations, interviewing of

reporting parties, trail cameras, tracking, telemetry, GPS locations, howling, and trapping during

investigations to gather evidence of wolf involvement. Hazing was used to move wolves away from

residences, recreational areas, or domestic animals in proximity to humans. Carcasses and other

attractants were removed from affected areas when appropriate.

Wolf-human conflict reports were documented in the Mexican Wolf Recovery Program Quarterly

0.00

20.00

40.00

60.00

80.00

100.00

120.00

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Depredations per 100 Wolves

38

Updates which can be accessed on the Service’s Mexican wolf web site at

https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-wolf/library.

Figure 11: Total number of wolf-human conflict incidents by incident category and state in 2022.

0 0

18

0 0

3

0

5

10

15

20

25

Imminent Threat to Humans Potential Threat to Humams Nuisance Incident

No. of Wolf-Public Incidents

Arizona New Mexico

39

Figure 12: Number of confirmed wolf-human incidents by category 2017-2022.

c. Proactive

Management

Various proactive management activities were utilized to reduce wolf-livestock conflicts during 2022.

These management approaches and tools may include:

• Altering livestock grazing rotations: moving livestock between different pastures within USFS

grazing allotments to avoid areas of high wolf use or depredations. Project personnel met with

USFS District Rangers, biologists, and range staff to discuss livestock management options during

the wolf denning season and to address potential conflicts between livestock and wolves. During

2022, alteration of livestock grazing rotation schedules was implemented once to minimize wolf-

livestock conflict.

• Carcass Removals: attractants such as livestock carcasses are removed when the presence of

those attractants could draw in wolves and lead to increased conflict. Carcass removal is

prioritized in areas with active calving and prior to denning season to reduce the likelihood that

wolves will localize and den in an area where cattle are present. Carcass removal is not

possible in some areas due to access issues. During 2022, the IFT removed 54 livestock carcasses

to minimize wolf-livestock conflict.

• Diversionary food caches: carnivore logs or road-killed native prey carcasses provided to wolves

in areas to reduce potential wolf conflicts with livestock and potential nuisance incidents.

Diversionary food caches were established in areas where depredations had occurred or were

likely to occur for 14 known packs and one uncollared wolf area during 2022. Supplemental

food caches were established in association with 4 packs during 2022. These supplemental food

caches can also act as diversionary food caches by reducing the potential wolf-livestock conflict.

0

1

2 2 2

0

4

21

14

22

17 21

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

No. of Wolf-Public Incidents

Imminent Threat to Humans Potential Threat to Humans Nuisance Incident

40

• Hay an

d supplements: feed and mineral supplements purchased for livestock producers who opt

to contain livestock (e.g., cows with young calves) in smaller, more protected areas during

livestock calving season or wolf denning periods to reduce the potential for conflict between

wolves and cattle on grazing allotments or private property. Our partner agencies and NGOs

did not purchase hay or supplements to mitigate conflicts between wolves and livestock in 2022.

• Hazing: human presence, rubber bullets, pyrotechnics or other combinations of light and sound

used to scare wolves from an area. Wolves were hazed on foot or by vehicle in cases where

wolves localized near areas of human activity, displayed nuisance behavior, were present in

areas with recent depredations on livestock, or areas with potential for wolf-livestock conflict, or

if found feeding on, chasing, or killing livestock. When necessary, wolves were hazed to

encourage an aversive response to humans and to discourage nuisance and depredation

behavior. In 2022, the IFT conducted hazing activities for 454 personnel days (e.g., multiple

personnel hazing on the same day would count as 2 or more personnel days). These activities

resulted in successful hazing on 250 occasions.

• Livestock producer contacts: the IFT regularly contacts livestock producers via phone calls, text

messages, emails, and site visits. In particular team members directly notify affected producers

of substantial wolf management actions, including animal translocations, foster operations,

animal removals, and annual count/capture operations. The team notifies livestock producers

and landowners when a wolf dens on or adjacent to active allotments or private property.

Similarly, the IFT coordinates with affected producers when implementing conflict-management

activities and increases communications with producers experiencing conflict. In addition to direct

communication with affected stakeholders, the IFT maintains a public internet-based location

map providing buffered, offset locations that is updated every two weeks. This map allows

livestock producers, landowners, and land managers to independently stay informed on wolf

locations and movements. All IFT members are expected to be available to respond to inquiries

from affected stakeholders.

• Radio telemetry equipment: radio-collar monitoring equipment issued to livestock producers to

facilitate th

eir own proactive management activities and aid in the detection and prevention of