Colby College Colby College

Digital Commons @ Colby Digital Commons @ Colby

Honors Theses Student Research

2022

The New Mainers: An Exploratory Analysis of Healthcare The New Mainers: An Exploratory Analysis of Healthcare

Experiences in the Somali Bantu Community Experiences in the Somali Bantu Community

Jordan R. McClintock

Colby College

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses

Part of the Public Health Commons

Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this

site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial

purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

McClintock, Jordan R., "The New Mainers: An Exploratory Analysis of Healthcare Experiences in

the Somali Bantu Community" (2022).

Honors Theses.

Paper 1384.

https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/1384

This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital

Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital

Commons @ Colby.

The New Mainers: An Exploratory Analysis of Healthcare Experiences in the

Somali Bantu Community

An Honors Thesis

Presented to

The Faculty of the Department of Science, Technology, and Society

Colby College

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

Degree of Bachelor of Arts

By

Jordan Rhyse McClintock

Waterville, Maine

May 13, 2022

1

Signature Page

Examined and Approved on

By

Advisor

Department Chair

Reader

2

Abstract

Healthcare inequities within the United States’ Western model of medicine have

existed for hundreds of years. The purpose of this year-long project was to analyze the

existing qualitative and quantitative studies of healthcare barriers for the Southern Maine

Somali Bantu population, as well as compiling narrative pieces from Maine

non-governmental organizations that provide community resources. In doing so, the idea of

healthcare access and literacy was analyzed through means of understanding systemic

barriers. Overall, the findings of this exploratory project point to a lack of cultural humility

within medicine, the importance of recognizing intersectional identities in quality of

healthcare, and the usage of healthcare literacy as a means for the healthcare system to

exclude the Somali Bantu community from receiving equitable care.

3

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Ashton Wesner for her continued guidance and support

throughout the academic year. Without her, I would never have been able to reach deep

within myself and create a project that encapsulates my history and the amazing healthcare

advocacy work being done for marginalized communities. Another thank you to Professor

Aaron Hanlon for providing academic support as my STS departmental advisor; he and

Professor Wesner definitely believed in me more than I did in myself. A further thank you to

Professor Nadia El-Shaarawi for being my outside reader and being one of the first to

introduce me to the New Mainers generation, as well as their experience with access to

healthcare. To my wonderful STS seniors, thank you for the valuable feedback and the

motivation during class periods. I would also like to give a huge thanks to Mohammed

Hassan from the Main Immigration Access Network (MAIN) and Muhidin Libah of the

Somali Bantu Community Association for their invaluable anecdotes about empowerment

and advocacy within the Somali Bantu healthcare experience. Lastly, I would like to thank

my mother Jenssie Flores-McClintock for not only inspiring my thesis but inspiring me to

continue advocating for healthcare rights in marginalized communities. Her incredible and

moving story as a displaced child arriving in the United States without healthcare advocates

is a testament that change must happen.

4

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 5

Introduction 6

Literature Review 9

Methods 14

Anecdotes 28

A Field Analysis of Maine Access Immigration Network 31

A Field Analysis of the Somali Bantu Community Association 39

Conclusion 42

Bibliography 44

Appendix A: Outreach Materials 51

Appendix B: Somali Healthcare Infographics 54

5

Introduction

A History of Somalis in Maine

Violence, prejudice, and injustice. All are rooted into the history of the Somali

Bantu people and the stigma surrounding their forced enslavement. In the late 20th

century, a civil war broke out in Somalia and the Bantu group was immediately targeted.

For historical context, the Bantus are a minority group in Somalia that have been

discriminated against for being culturally, ethnically, and socially different from the

majority Somali group. As early as the 16th century, ancestors of the modern-day Bantu

groups were forcibly brought from Zanzibar as enslaved laborers on plantations. The

effects of colonization were apparent in the treatment of the Bantus in the years to come.

Italy, which gained control of Somalia in the late 19th century, had made the state a part

of the protectorate Italian Somaliland and allowed for the continued enslavement of

Bantus in agricultural labor.

Due to the years of stigma surrounding the Bantus, the Italians also treated Bantu

as inferior to the ethnic Somalis. Feelings of negative sentiment and animosity had

perpetrated violence for centuries and it came to a sudden head in the late 20th century. In

the aftermath of the Cold War, Somalia’s dictator-president Siad Barre had nationalized

land, which disenfranchised Bantu farming communities across Somalia. His plans to

invest in different areas across Somalia through educational, infrastructural, and

healthcare reforms tactically excluded Bantu-centered areas. Barre’s reign in Somalia was

6

marked by turmoil and his relationship with the United States directly affected the

country’s stability. The United States had provided military and economic support to

Somalia due to its strategic position in terms of its location between the Persian Gulf and

the Indian Ocean (SBCA). After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the United States severed all

support to Somalia and Barre was forced to abdicate power to anti-government coalitions

and fled to Kenya. The Bantus, under Barre, had faced prejudice in all forms but his

military support had somewhat quelled extremists who sought to target them. With his

government left in shambles, the Bantus were the first to be targeted. The Somali Civil

War yielded heinous war crimes that, to this day, have not been given proper attention

within the international justice system. At the time, it was identified as, “The worst

humanitarian disaster in the world today” by the former director of the U.S. Office of

Foreign Disaster Assistance Andrew Natsios. Bantu families were forcefully evicted from

their land and subjected to cruel and violent torment. Between anti-government militia

movements and famine, the Bantus were forced from their homes and displaced both

physically and mentally. Many of them fled across domestic borders towards Kenya.

Even more fled the African continent and found temporary placement in other countries.

Families looked towards the United States and, after months of research, ultimately chose

Maine (MAIN).

The United States’ most northern state was an ideal relocation because of low

crime rate, affordable housing rates, and structured education. Here, the Somali Bantu

community could start fresh after being faced with violent backlash in their home

country. When they traveled 7,237 miles away to the greater Lewiston area, what they

7

found was a little more than they bargained for (Iftin 2015). They arrived in the New

England metropolitan area and were immediately met with obstacle after obstacle as they

tried to settle within the new healthcare system. Families, young adults, and elderly all

struggled to find and access safety nets of hospitals, clinics, and other providers. The

question that came about was: How could the United States accept a community of

people that they could not- and would not- provide equitable access to healthcare for?

Structurally, United States healthcare is built upon a bureaucratic system of an established

hierarchy that prioritizes market-based regulations and lacks the ability to provide

universal quality care for even its citizens.

In terms of the Somali Bantu community of Maine, the important questions

regarding healthcare access and literacy can become convoluted in regional policies and

dominant hegemonic narratives. In approaching their healthcare experiences, there can be

a few derived hypotheses.

Firstly, Somali Bantu healthcare literacy and access is affected by the systemic

prejudice present in the domestic healthcare system. This looks like a few different

things; there is the way providers are trained in medical school in terms of excluding

intersectional education and considering the differences between patients. There is also

the idea of community healthcare workers not being available in quantities to meet the

needs of the Somali Bantu community.

The second piece surrounding the focus of the thesis is healthcare literacy being

used as an “othering” technique by the system, which produces the highlighted barriers of

this paper. Essentially, health literacy is the ability of an individual to understand and

8

navigate their health options and navigate. In terms of the Somali Bantu community, it is

used as a way to alienate them further from general healthcare access. Rather than

reconcile with the reality that literacy coincides with transparency and access from the

providing government, it is used as a way to blame and reinforce the existing barriers. In

terms of the Science, Technology, and Society role on how to address this plight and its

role within a medical setting, there is the societal aspect of ingrained medical racism that

affects access and health literacy. On a larger scale, the technology piece of how language

translation and other intersectional health techniques could be utilized to create a more

equitable healthcare system. Piecing together the different aspects that surround the

Somali Bantu community’s healthcare experience, this thesis is a contextual analysis of

the healthcare experience and how the industry disadvantages The New Mainers.

Literature Review

Identifying and Categorizing General Barriers

Concerning the framework of my project, some of the cornerstones include

Central Maine publications. The Bowdoin-based CORE piece overviews some of the

most important aspects of my research, including the facets that exclude the Somali

Bantu community from healthcare options on both a regional Maine and national level. It

9

is the framework of my own research in terms of what questions I asked. It offers

valuable stakes in the argument because it provides contacts I utilized within my field

research. In addition to providing insight on the Maine-based healthcare system’s

relationship with the Somali Bantu community, it analyzes the substandard provider

training available. This is where Warwick Anderson’s piece on “Teaching Race in

Medical School” comes into play as an important STS perspective in the difference

between race and ethnicity in medicine. The fine line is seldom understood by providers

and can serve as an additional barrier to marginalized patients. This aspect in my

literature review can be tied nicely together with the work of Hayley Fitzgerald, who

discusses the six main stressors on Maine-based Somali Bantus; “economic stressors,

discrimination, difficulties with acculturation due to language differences, parenting

differences, and pressure to find employment.” Together, these pieces bring together a

resulting analysis that coupled with my own research.

Healthcare Narratives

The backbone of my research centers around narratives from Somali residents

themselves about what they have experienced. Northeastern University- based Ashley

Houston conducted a study on young Somali adults trying to make their way through a

broken system that gives tremendous insight on how there are inequities that contribute to

the societal hierarchy. Houston’s piece shows that there is inequity for those of median

age. Additionally, this section of my research is where autobiographies play a very

10

important role in shaping these types of experience. They also helped supplement

arguments posed by publications that focused on Somali Bantu mothers, who had

valuable commentary on provider’s verbal etiquette. Abdi Nor Iftin’s acclaimed

autobiography details a young man’s journey to Yarmouth, Maine amidst the turmoil of

his home country and new country. His struggles within the system give narrative

perspective on what the studies show through logistics. After interviewing the

agricultural organization the Somali Bantu Community Association, Iftin’s unfamiliarity

with the United States’ frigidity towards identity becomes clear with the system’s

inability to shift towards more open conversations about healthcare access and literacy.

Cultural Humility: A Lack of Compromise in the Western Medical Model

The word cultural humility was not officially recognized until the late 1990s. As

the Boston Medical Center explains in their Policy and Industry piece, cultural humility

“involves understanding the complexity of identities - that even in sameness there is

difference- and that a clinician will never be fully competent about the evolving and

dynamic nature of a patient's experiences”. In approaching medicine with this mindset,

ideally, there will be a reduced amount of bias within practicing medicine because of the

physician’s awareness of their own implicit prejudices. While not a perfect solution to the

large abyss that is health inequity, it does allow for physicians to somewhat embrace both

11

sides of the provider-patient interaction through an understanding of identities. In terms

of the patient, it recognizes what the patient needs as opposed to the mentality that

provider training is flawless.

A valuable piece that offers up an interdisciplinary approach in recognizing what

is important to the patient in healthcare is “Caring for Somali women: implications for

clinician-patient communication” by Jennifer Caroll and a Rochester-based team that

interviewed 34 Somali women in Rochester, New York. This study focuses on the

alternatives for the existing Western medical model that excludes BIPOC individuals-

including women- that may offer potential solutions to the obstacles faced. Increased

patient-provider interaction, which included language interpretation and health literacy

within the clinical setting were found to be successful cornerstones. It couples well with

Susan Bell’s piece on how language interpretation in clinical settings was very effective

in fusing together provider-patient relationships within Somali Bantu communities. This

type of tool is very important in healthcare because being able to understand the patient

in every sense of the word can allow for a more efficient procedure. An interesting part of

the alternative side of medicine comes through the integration of more healthcare workers

within the Somali Bantu community that are designated as community health workers

(Cowenhoven 2017). With this, it is important to understand what a community

healthcare worker is. A large umbrella term, community health workers wear a few

different hats. They are often synonymous with outreach workers, family advocates,

health educators, medical liaisons- among other titles. Essentially, their job is to connect

marginalized communities with health organizations and clinics. They may provide

12

translation or interpretation services and are a pipeline to different health. What this

recommendation brings is a fascinating perspective where perhaps MD and DO

practitioners should not be at the forefront of health. It should in fact be workers who are

trained in specific Somali Bantu healthcare.

From a historical point of view, the Black Panther Party’s creation of the Peoples’

Free Medical Clinics was something that resonated with some of the opinion pieces

within my research. In a sense, the people run the medical system and do it in spite of the

existing hegemonic system. While the situation between The Black Panther Party and the

Somali Bantu community differ in historical context, they have the same issues present.

That being there was a lack of support and specialized care from the government for

Black bodies, which meant there were people needing to take community healing support

into their own hands. As of right now, there is no universal model of medicine that is

conducive to all different races and ethnicities. Particularly in the United States, the

medical industry thrives on making sure all practices and training are completely

uniform. With uniformness comes a lack of recognizing identity.

Fatuma Hussein of the Immigrant Resource Center of Maine and the United

Somali Women of Maine stated it perfectly when she discussed the idea of community

and ancestral healing finding a balance with Western healthcare in her keynote lecture at

the University of New England. The way Fatuma looks at it, when a child is fussing or

does not feel well- parents may read the Quran to them as a way to facilitate the

community’s spiritual healing. In the Western version of healthcare, culture is not

embraced as a factor into how healthcare or wellness is perceived. Spirituality and

13

community healing is not embraced within medicine, which is not only challenging for

different marginalized communities to understand but, it also perpetuates the idea that

there is only one right way to practice medicine and understanding your patient is not at

all something to consider nor think about.

Methods

A General Overview of Literature Analysis

Analyzing existing studies that encapsulate healthcare inequities through

quantitative and qualitative data, I also consulted Maine non-for-profits, governmental

organizations, and representatives from the Somali Bantu community. Combining both

into a capstone project that looks at barriers through an STS lens of how advancing

medical practices still exclude marginalized communities through inadequate provider

training. In terms of procedure for my study, I analyzed existing studies that specifically

look at different experiences in the Somali Bantu community. Anecdotal evidence points

to the idea that Somali Bantu community members within the Southern Maine area have

experienced healthcare experiences. From families, young adults, to elderly, it is clear

across the board that there are discrepancies in the quality and security of their

healthcare. Identifying different commonalities across each correspondence and

identifying the most prevalent barriers and how they structure into healthcare

14

experiences. Each representative received a flexible questionnaire with guiding questions

that allowed for a more informal conversation to take place. The latter was centered

around a few central questions that coincide with my research hypotheses: In terms of

identities, do Southern Maine healthcare providers have training that specializes in

cultural humility? Describe the differences in obtaining clinical care within the Somali

Bantu community between someone with documentation and someone without. What

does representation look like in terms of care providers that speak Somali? These

inquiries helped loosely guide their responses for insight into the healthcare experiences

of Somali Bantus as providers and non-for-profits giving aid.

A Global Perspective

2000 was the year of a new millennium. Commerce, technology, and infrastructure

was advancing at a rapid rate. Consequently, it was also the turning point in the Somali

Civil War, which had begun in 1991. As previously discussed, the overthrow of the

government resulted in tens of thousands displaced Bantus from their land by militia

forces. The resettlement of Somali Bantus in the United States was a whirlwind of

activity, as about 1,000 of them set their sights on Southern Maine (Huisman 2011). Upon

their arrival, a term that was used to describe the growing Somali Bantu population in the

small cities stretching across inland and coastal Southern Maine was “The New

Mainers”. Referencing their recent settlement and new contribution to Maine’s social and

15

cultural profile, it became used to reference the new generation of Maine inhabitants that

would share their experience with the domestic community and attempt to start a new

life.

When fleeing your home country to settle in an unfamiliar one, there is already an

immense amount of pressure. Adding the additional worry of how you will be perceived

in a medical setting is almost unimaginable. Now, in terms of medicine, what are the

inequity factors that drive the resulting biases in medicine?

Nina Sun discusses in her piece, “Human Rights and Digital Health Technologies”

how digital health technologies can contribute to expanding health inequity, widening the

“digital divide” that separates those who can and cannot access such interventions”.

What this entails is that racial biases perpetuate racial grouping and stereotyping that

affects the type of care they can receive. This idea is not a tangible one but, after

conducting my own research, was revealed through correspondence with the

organizations.

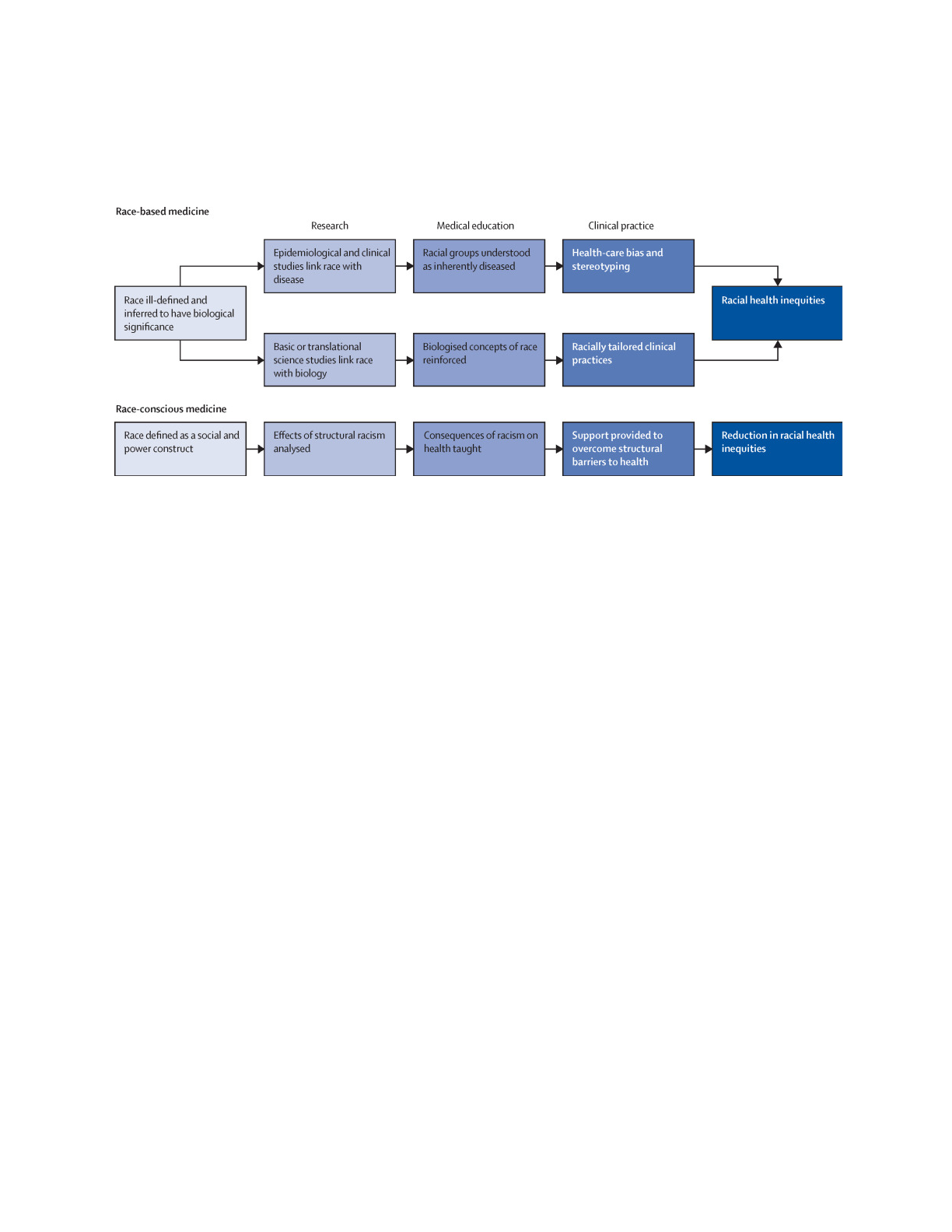

Referring to Figure 1, the difference between race-based medicine and

race-conscious medicine can be determined. The type of model that we use in the United

States is centered around race-based medicine. This type of idea referring to race as a

medical technology is something that my colleague Fariel LaMountain explored further

in her thesis. From a STS point of view, the idea of race in medical school is something

that factors heavily into how people are equipped for care. Warwick Anderson’s

“Teaching `Race' at Medical School” is an interesting look into how race and ethnicity

are often two synonmyous terms that are not usually understood. Anderson offers up the

16

notion where because of this, there is a lack of understanding concerning how people

need to be treated with this type of identity in mind.

Figure 1. A diagram that shows the difference between race-conscious medicine and race-based medicine. The idea

is to have one recognize social constructs and have providers engage in cultural humility with a recognition of

system biases.

Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to

act. Lancet. 2020 Oct 10;396(10257):1125-1128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6. PMID: 33038972; PMCID:

PMC7544456.

Thus, the small state of Maine unfortunately experiences this trickle down effect in

healthcare policies because of the societal racism that is deeply ingrained. In terms of

what types of experiences are happening in Southern Maine, there is a very good insight

in what occurs through studies done by Northeastern institutions. Ashley Houston’s

research based from Northeastern overviewed young Somali adults with ages ranging

from late teenage to adult years. Within the healthcare system, they were not afforded

equal opportunity because of socioeconomic boundaries that centered around cost. It was

17

clear that provider training did not contain any kind of cultural humility, or a respect and

understanding of different aspects of a person’s identity.

This study is not the only look into the types of barriers that exist. There are a few

other qualitative and quantitative studies that not only identify barriers but also look into

how there are alternative models for facing these issues. The truth is that the current

model is ineffective because it refuses to help marginalized communities which, in turn,

continues to perpetuate violence against non-white communities. The first thing that is

important to note about the barriers is that they can be summed up into four main

categories.

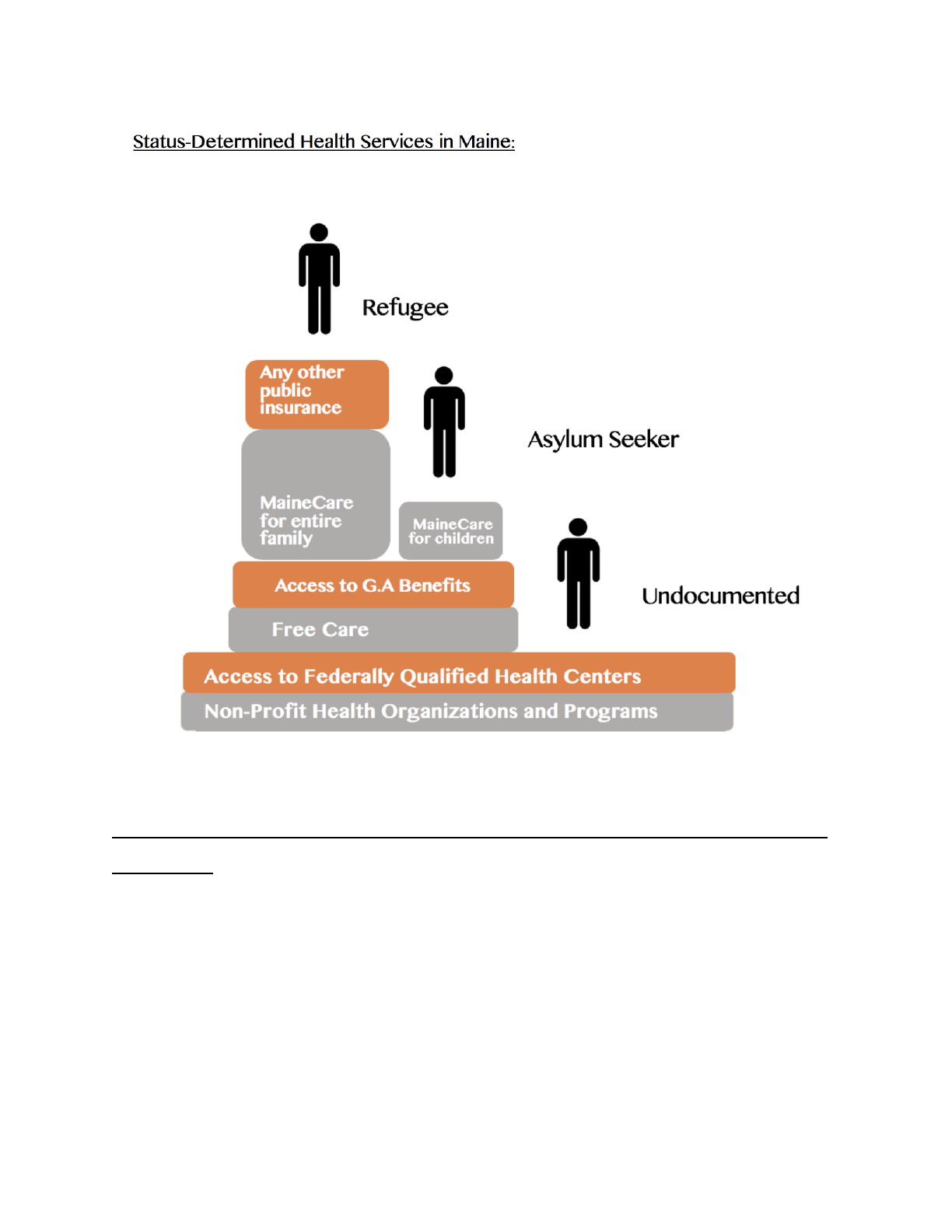

A large one is the national health care system, which of course offers a strict

criteria that cannot always be met because of documentation status. This is something of

note within the Somali Bantu community because there are different situations for

different individuals. There are three types of classifications that determine health

resources from not only the national level but the Maine level (Agrawal 2016). This

project is a cumulative analysis of the healthcare experiences through access and literacy

of the entire Somali Bantu community however in terms of what is available, it differs

between those who have specific status over others. This is the reality of Western

healthcare so, it is important to acknowledge this aspect in the overall thesis.

Figure 2 is a visual representation of what this difference looks like through a

metaphoric hierarchy. Refugees have access to national healthcare, regional healthcare,

and most public insurances with benefits for employee security. They are given this

refugee status while still outside the United States and sponsored. Asylum seekers are

18

different in that they have been status at the point of entry or after entering their new

country. They are afforded less health care opportunities than refugees in that they are

able to have regional healthcare for minors but not entire families nor are they able to rely

on employee benefits (Xin 2018). The last are undocumented individuals, who have

extremely limited access to federally funed programs.

There is a national crisis in terms of undocumented folx not receiving proper care.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, “53% of domestic

farmworkers” and laborers are undocumented. Those who utilize the existing medical

system hover between 38% and 53%. What this entails is undocumented folx, including

those in the Somali Bantu community, being afraid or untrusting to utilize resources. This

comes as no surprise, as there is generational distrust within marginalized communities

because of the systemic racism present within our healthcare system.

19

Figure 2. This diagram shows the designations between refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented folx.

https://community.bowdoin.edu/news/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Major-Barriers-to-Healthcare-Access-for-New-

Mainers-2-1.pdf

What makes this so complicated is that all three exist within the Somali Bantu

community and all three receive different levels of care. Something that was very evident

within the narratives of both Cynthia Anderson and Catherine Besteman’s novels was that

there are adjustments for not only those displaced but, those who live in communities that

20

gain new neighbors over a period of time. This type of societal reaction is something that

also factors into the psychological factor of receiving healthcare. In short, because there

are sometimes push backs against displaced individuals inhabiting a new place, it can

trickle into the quality of healthcare received. For example, within the initial surface

research conducted, there was not a percentage available of healthcare providers that

could speak Somali and engage with different aspects of their patient’s documentation

status, gender identity, income, health conditions, family accomodations, and other

aspects. Language is extremely important in giving healthcare to marginalized

communities and Bell’s piece ties in how it is so important to directly understand a

patient’s symptoms, which can be hard to do if that is a barrier.

Another layer is gender identity’s representation in the healthcare field. Jennifer’

Caroll’s overview of Somali women and a study about patient communication found that

many of the Somali women preferred having a female identifying provider in the room

during their care. This is something that is often overlooked as a patient necessity but it

factors heavily into the overall quality of care. This was further explored in Hill’s piece

on Somali natal care- specifically how expectant or current mothers have a sense of trust

in their providers when they feel they have a sense of control in their situation. Having a

sense of cultural humility and understanding of intersectionality in the workplace is

something that can be so valuable to caring for another human being.

Additionally, having an element of health literacy between patient and caregiver is

another level of comfort to the parties involved. One study method used is a parameter of

patients’ medical awareness called Patient Activation Measure (PAM). Lower PAM

21

scores from patients reflects a lower health literacy rate. According to a study done, “24%

of Portland respondents had a Level 1 score”. Level 1 is the lowest score and is indicative

of the fact that marginalized Portland communities could greatly benefit from community

health workers (Cowenhoven 2017).

Having this would lower stigma in asking for help, as well as prioritizing mental

health. Displacement effects on mental health are large parts of how people can function

in new environments. The 5 stressors that were deduced from mental health effects within

Somali communities were broken down into: “economic stressors, discrimination,

difficulties with acculturation due to language differences, parenting differences, and

pressure to find employment.” (Fitzgerald 2017). Mental health effects of marginalized

folx is something that factors into why organizations like the Black Panther Party

organized their own medical care. Alondra Nelson’s book gives a look into how social

justice and medicine goes hand in hand through the lens of dismantling systemic racism

within the hospital system. While this was decades ago, it does offer an alternative

method into creating a community healing system. Ultimately, what this project entails is

possibly exploring a model that would be better suited for the Somali community.

“Improving the wellbeing of the world’s migrants requires an intersectional lens that

focuses on the diverse circumstances and locations in which migrants are situated”

(Spitzer 2019). In other words, the only way Somali Bantu healthcare will improve is if

an intersectional approach is made.

22

Field Research: Interacting with Maine Healthcare Advocacy Partners

During the research portion of my thesis, I wanted to integrate my own

commentary into the existing literature about the Somali community. Their healthcare

access is something that has been in conversation for a long time. As a precursor, I want

to stress that I was fortunate enough to be privy to some very important anecdotal

narratives from the non-governmental organizations that represent and support the Somali

Bantu community. However, I am simply an academic that had the opportunity to do so

and in no way represent the healthcare plights of the Somali Bantu community. My

overall goal for this thesis was to have an analytical look at their experiences and

hopefully provide a platform to further amplify their voices. The advocacy done by their

community and affiliated associations for a more inclusive healthcare system is beyond

the work that I could possibly do within a year.

During the planning stages of my thesis research, I took inspiration from a few

different peer-reviewed sources in terms of how they conducted field work to collect

narratives regarding Somali Bantu healthcare in the Maine and Greater New England

area. Close attention was paid to what types of questions or hypotheses were being posed,

what specific focus of healthcare inequity was being studied, and how they analyzed their

findings.

23

When thinking about the methods used within my research, something that

distinguished Matteen Hakim’s piece is its presentation format and the fact that it actually

is a student project for a medical student in their rotation during their final year of study.

Hakim’s focus on the Somali community of Southern Maine- specifically Lewiston- and

the different types of barriers within the community parallels my own thesis topic. The

presentation is broken into what problems appear to be, the pecuniary implications of

public health, anonymous community perspectives, the methodology (incorporating

Somali voices into the healthcare narrative), the results (or perspectives given) from

interviews, limitations, and recommendations for future research. This piece was a really

important stake in the methodology because it does have similarities to the way I am

approaching analysis for healthcare barriers. Additionally, it mirrors the interview style of

community outreach that I hope to accomplish in my ethnographic approach to interviews

in the field. One of the main aspects of the piece that I also found to be similar to mine

was the types of people being interviewed and the approach to advocating for community

healthcare workers.The future research area of the presentation was also interesting

because I feel that expanding on the point of increased language accessibility is

something that my project looks at in my written analysis of different barriers. Hakim’s

final product is something that offers great insight on the healthcare provider side of

Somali healthcare literacy and accessibility.

24

As a methodology, it matches up with my vision and also offers up important

potential points about connecting community advocates with healthcare support

organizations for my own research. The second piece that supplements Hakim’s piece and

offers up an interesting perspective for student researchers within the Lewiston area is

authored by three graduates, who had a similar methodology to both me and Hakim in

terms of conducting field research. The one thing that makes it different is its focus on the

transportation access issues of the Somali community, which is something that I had

explored at all within my research. It is something that I feel needs to be explored within

my paper. There are points brought up about not simply just logistic access but, there is

the notion of biases within those who are supposed to provide transportation. There is

also the idea of barriers not being fully understood by domestic-based organizations,

which may not know how to collaborate with community advocates (Caldwell 5).

My thesis is simply a hybrid ethnographic-analytical look at the work they do in

conjunction with the peer-reviewed sources that provide quantitative data. The two main

organizations I had the privilege of interacting with were the Maine Access Immigration

Network (MAIN) and the Somali Bantu Community Association (SBCA). My key

contacts for each were Mohammed Hassan and Muhidin Libah, respectively. Hassan is a

community health worker originally from Somalia and later moved to Syria where he

worked with Somali refugee families. Conversational in over four languages, Hassan has

practiced medicine in Somalia, Saudi Arabia, and partnered with the United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees in Damascus, Syria. He joined the Portland-based MAIN

specifically to provide care for those that are disadvantaged by the public system because

25

he has a huge commitment to ensuring equal access for all those who do not know how to

advocate for themselves or their families.

Muhidin Libah is the executive director of the Somali Bantu Community

Association in Lewiston. He arrived in Southern Maine around 2001 and grew up in a

Kenyan refugee camp following the Somali military conflict. He attended the University

of Southern Maine and founded several non-for-profits in addition to the SBCA. His

mission upon arriving in Maine was to empower Somalis through land cultivation and a

sense of community. Agricultural wellness is a pinnacle in Somali Bantu culture and

something that was difficult upon arriving in the United States was for the community to

preserve their culture. Referencing back to Fatuma Hussein’s lecture about Western

medicine, there is a separation between patient and provider in the clinical setting that

goes far beyond just medical expertise. When a patient arrives into a space where the

provider giving them catre does not look like them, there is a high chance of implicit bias

concerning that individual’s identity and the care they can receive.

Technical Procedure

To better understand the role of the non-governmental organizations that represent

healthcare advocacy for the Somali community, my original plan was to hold interviews

with organization representatives using either the phone or a virtual software. Before the

interviews, there would be a consent form sent, which is included in this methods section.

During the actual interview, there would be guiding questions that would steer the

26

conversation but give the interviewee full autonomy and treat the prompts as a starting

off point. The questions were structured around understanding exactly what the

organizations do, the role the organization has in the healthcare conversation, the effects

on the Somali Bantu community of the medical training for providers in Maine, and the

overall experience of the Somali community in the United States’ medical system. The

idea behind this type of field research was to combine these collected narratives with the

literature analysis to better prove or disprove some of my hypotheses.

In terms of limitations, there were some challenges that did influence the way I

conducted my research. Due to COVID-19 complications and important work occurring

on a day-to-day basis for the organizations, my interactions were limited to email

correspondence. Essentially, all materials were sent over email and the questions turned

into shorter essay prompts for the representatives to answer. In an ideal world, interviews

would be conducted face-to-face, however, because of health concerns due to the

pandemic, safety had to be prioritized.

Following the correspondence, I was able to compile key points from both

Muhidin Libah and Mohammed Hassan that were incredibly beneficial to my own field

analysis. The following anecdotes from both are direct quotes in response to the

open-ended questions sent to them over email. Incredibly thorough, the answers reflect

my initial hypotheses very strongly in terms of systemic barriers factoring into the quality

of care due to existing prejudice. They also touch upon how healthcare access and

literacy is directly linked to the ease of navigating a system that does not take

intersectionality into account. An interesting aspect of both these organizations is that

27

while their missions are directly linked to forms of healthcare advocacy- whether it be

more resources to clinical care or agricultural health and wellness- they are both

incredibly different. However, their responses to the prompts yield similar themes of

access inequity and the difficulty the Somali community has in terms of a lack of cultural

humility within Western health. This was incredibly fascinating because the organizations

have different missions but nearly the same fundamental values of connecting and

empowering the Somali Bantu community. It is clear within the anecdotes provided to me

from both Hassan and Libah that the healthcare experiences of the Somali Bantu

community and the organizational approach to them operate in a variety of different

ways. For example, the SBCA’s health and wellness commitment through agricultural

empowerment was a wellness initiative that I had never been exposed to. However, after

learning more about the Somali Bantu identity and what the organization does, the

importance of health and wellness through the growing, harvesting, and celebration of

food should absolutely be recognized as a form of healthcare.

Anecdotes

Maine Access Immigration Network (Mohammed Hassan)

Explain a little about what your organization does to support the Somali

Community?

28

“We are a non-profit ethnic based community organization that helps immigrants

who speak different languages including the Somali speaking community in Maine by

providing health literacy educational meetings to communities in partnership with major

healthcare providers, helping newly arriving immigrants access to social services such

healthcare, food, housing and other needs by connecting them to providers in Maine. We

also advocate when needed to certain vulnerable individuals. We partner with providers

to help them perform research projects for the communities we serve”.

What is the experience of a newly-arrived family or individual in terms of obtaining

physicals/general health check-ups?

“Newly arrived Somalis come to the US with different immigration categories

such Refugees, Family Reunion and rarely as Asylum seekers (undocumented) . Free

health care coverage depends which category of immigration they arrive here, those who

enter as refugees can get Medicaid health insurance which covers all health and other

social services at least for the first few months until they earn income while asylum

seekers are not eligible free healthcare coverage except children and pregnant women,

same are also those who enter with family reunion visa”.

How have the communities of Southern Maine transitioned after the arrival of the

Somali community?

29

“Somali communities in Maine experience hardships due to all barriers such as

language, culture, and the weather but they transition from being an immigrant to

becoming hard working individuals with citizenship while their children enroll in higher

education and integrate with the mainstream population and we help them navigate the

complicated American health care system”.

What does representation look like in terms of care providers that speak Somali?

“Healthcare providers are mainly white and do not speak Somali language but,

providers use interpreters although lately MaineHealth is trying to diversify their

residency programs with few Somali providers who speak Somali Language”.

Describe the differences in obtaining clinical care within the Somali community

between someone with documentation and someone without.

“As mentioned above those who legally arrive are eligible to certain level of

service depending income and other factors while undocumented Somalis are not eligible

for state or federal healthcare coverage except emergency medical care that may be billed

to them”.

30

Somali Bantu Community Association (Muhidin Libah)

“Somali Bantus are people who come from rural areas where there were no

hospitals, running water [nor] medical services. When the people came to the USA they

were overwhelmed with many different Western diagnoses and treatments, which were

foreign to our community. The medical reconciliation's mission is to make sure our

people get clear information about the new medical systems.

Somali Bantus were farmers in Africa, they used to live on the banks of the rivers

captivating the land and fishing, hunting, and gathering, farming comes with traditional

healing and treating diseases, farming was not only producing food, but it was also a way

of life. Everything was around farming”.

A Field Analysis of the Maine Access Immigration Network (MAIN)

The mission of MAIN is to “[address] refugee/asylee health literacy, health care

enrollment, and coordination of health care services”. They are funded by the Office of

Refugee Resettlement Ethnic Community Self Help Grant, the Maine Health Access

Foundation and the Maine Community Foundation. Partners they have around Maine are

Greater Portland Refugee and Immigrant Health Collaborative, University of New

England CHANNELS Project, Care Partners, MaineHealth, and Mercy Hospital.

Renowned for its commitment to providing a bridge between marginalized communities

31

that are newly settled in Maine and health resources and practices around the state, its

staff are passionate about making access more available. Their executive staff were all

new to Maine and its health systems so, they have a deeper empathic understanding of the

Somali Bantu community’s struggles. Their organization was one that immediately struck

me as an important outlet to consult because of the staff’s personal connection to

healthcare access, the vast resources they provide, and their plethora of community

healthcare workers available.

Mohammed Hassan is one of these community healthcare workers and he was able

to provide me with more context about MAIN and the different experiences that occur in

the healthcare system. One thing that MAIN does to address the issue of literacy and

access is providing educational meetings for those that need assistance navigating the

healthcare system. As Hassan articulated, when new arrivals enter the state of Maine,

they immediately become a number. Everything depends on status and even those who

enter Maine with some type of citizenship do not always qualify for benefits. Something

that was quite shocking that Hassan revealed was the fact that emergency services are

often the only qualified medical care for the Somali community and yet they are often

billed for it. This goes hand in hand with the idea of rooted systemic prejudice affecting

the care they can receive. Even though there are those in the Somali Bantu community

that technically qualify for Medicaid and regional healthcare, these benefits are short

term and financially unreasonable.

32

Even more limiting are the opportunities for undocumented members of the

greater Somali community. Referencing back to Darlene Ineza’s study, a direct quote

from a Maine-based physician is that “Undocumented don’t have a voice at all. In my

experience, I have never seen any undocumented patients” (18). This is echoed within

Hassan’s conversation with me; in my field research I was unable to obtain many

resources directly available to not only the undocumented members of the Somali Bantu

community but, all of Maine’s minority communities. No doubt this is a structural issue

overall in the United States, however, it seems so much more apparent in Maine because

of the state’s lower population density. The reality of the benefits available federally for

newer arrivals is that there are far and few between. Hassan’s experience is primarily

centered around connecting health services with Somali Bantu community members who

seek out guidance. Something that Hassan also does is being responsible for combing

through Maine healthcare legislation in order to better understand how best to help the

Somali Bantu community members based on their situation. This, I argue, is just another

reason why community healthcare workers are so important to marginalized

communities.

As explained in Warwick Anderson’s medical education training piece, there is so

much risk for biases when providers are simply given the general medical training that

operates on nearly a purely academic-level. There is no incorporation of socioeconomic

identity when treating patients, which is why initiatives such as the Black Panther Party’s

community clinics arose. There is so much room for error in treating patients that do not

33

have the same identity as their provider. In terms of my first hypothesis about prejudicial

influence on healthcare access and literacy, this was a watershed moment that occurred

during my research. It made me realize how far the roots of racism and classism reach

and their effect on not only the healthcare system but, the other systems that coincide

with how our medical model operates. This is a large-scale problem that has so many

controversial opinions on how to solve it but, the addition of community healthcare

workers into this pipeline eases the process of finding resources that accommodate

specific situations. Hassan’s role is a multifaceted one that takes on the role of a medical

educator, social advocate, and legal consultant. He encapsulates three very different fields

but is able to combine them into a role that specializes in providing equal access. This

type of role is the very antithesis for what the general Western healthcare provider looks

like. Rather than conforming to a homogenous-centric model of care, community

healthcare workers are responsible for zeroing in on the different communities that they

serve.

In being that healthcare advocate, Hassan’s job also focuses on essentially utilizing

whatever tools he can to bypass systemic barriers. These previously mentioned barriers

come from the existing prejudice not only in medicine but in all aspects of society. In

Kristin Langellier’s chapter of Applied Communication in Organizational and

International Contexts, the author discusses how when the Somali Bantus arrived in

Maine, Lewiston mayor Laurier T. Raymond wrote an open letter to Somali community

advocates and leaders asking for the discouragement of future arrivals. Following this, a

34

white supremist group called the World Church of the Creator held a rally in Lewiston,

declaring through anti-immigration sentiments that they were there to “save” the city. It is

with this that I argue, how could the medical system truly be impartial when our

government leaders are encouraging the exclusion of marginalized communities from

seeking safety in our country? These are the problems that community healthcare workers

such as Hassan seek to address through his advocacy work.

After having the opportunity to speak with Hassan, something that became a part

of the two-pronged hypotheses approach to my thesis was the idea of supplementing

existing medical providers with healthcare workers in the Western model. While this was

a more large-scale recommendation that I formulated after my research, it is certainly

something that I believe to be an important step towards stepping away from the idea that

literacy and access are not connected. They are both intertwined because of hegemonic

values concerning how the system makes it difficult for marginalized communities to find

and access resources while also having no sense of how to navigate the healthcare

system.

In terms of specialized branches of medicine, Hassan brought up an interesting

point about natal care for the Somali Bantu community, which was something that came

up in my preliminary analysis of literature. He discussed how there were certain

exceptions to the staunch criteria of regional healthcare for expectant mothers. There

were three main secondary sources for this thesis that looked at overall healthcare

experiences in a clinical setting for Somali women. One was a general overview of the

35

experience of Somali women in a clinical setting and the other two were more specific to

pre and post-natal care. The first publication was a qualitative study that took place in

Rochester, NY and looked at the provider-patient relationship for 34 Somali women.

While this was a study conducted in New York, it pointed to similar themes that were

found in other colleague’s publications about Somali women’s healthcare experiences in

Maine. In terms of access to emergency medical services, which often is the only one that

Somali women qualify for, one patient stated: [If I don’t] have transportation I can’t go to

the hospital. That’s the problem. And if I don’t have anybody to make the appointment

for me I can’t do it [myself]. Translators are needed.” (Carroll 340). This again ties back

to that idea of not having the ability to have access if one’s healthcare literacy is not

supported by existing systems. Another aspect of this study that touched upon the value

of understanding a patient’s identity was the level of comfort patients felt in settings that

were not male-dominated. The study found that 62% of patients were more comfortable

discussing their medical concerns if their provider was female-identifying. This is

touched upon in another piece on dynamics of both expectant and recent Somali mothers.

In a Portland-based journal article on group dynamics of Somali women, settings with

female nurses who had previously worked with the community yielded positive results in

“...[because] they had experience working with Somali women, they were able to develop

trust and comfort in the groups with a relaxed and conversational approach” (Hill et al.

74). This particular study explored the different taboo topics, such as mental health with

natal care, which is so important when talking about healthcare. It is a perfect

representation of how understanding and respecting your patient’s identity can make a

36

clinical visit run more effectively for both parties. The third piece on Somali women’s

health was a journal article from the Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health where

they discussed health literacy for a group of Lewiston-based Somali Bantu women. “The

authors found limited health literacy in a population of immigrant Somali women and

created historietas (comic-book style health education brochure) that could be utilized by

health care providers to improve communication and understanding of perinatal health,

including emergency cesareans and postpartum depression…”(Jacoby et al. 594). What

this article brings into the argument is another example of health literacy being limited

because of communication issues. These expectant mothers were not able to effectively

communicate their inquiries to providers because of a language barrier and a difference in

cultural understanding surrounding medicine. However, this is an issue that is directly

linked to how the medical model works.

Another important piece of the argument concerning health literacy that Hassan

provided more context to was the idea of language interpretation. According to Hassan,

most health providers do not speak Somali and are white-identifying. However, large

regional medical institutions, such as MaineHealth are attempting to bring in more

interpreters that can effectively aid in provider-patient interactions. Examples of how

non-for-profits are partnering with large health partners to create more translated

resources can be seen in Appendix B. Figures 3 and 4 refer to COVID-19 vaccine

information and safety protocols about how to respond if one were to come into close

37

contact with an individual who tested positive. It also gives helpful background on the

vaccines and where it is possible to get it administered around the state of Maine.

Figure 5 is an infographic that details the COVID-19 Vaccine Initiative within the

City of Portland Public Health’s Minority Health Program. The latter was founded to

include marginalized voices in the conversation about the COVID-19 pandemic and how

to provide access to prevention resources, as well as provide more information regarding

the available vaccines. These flyers were distributed to the greater Southern Maine area

where there is the highest concentrated population of Somali Bantus. There is a push

from those that have been advocating for the community for years to incorporate

technology such as language translation and interpretation. And, as Hassan stated, this

change is starting to happen. There is a need for even more providers that can speak

Somali or have an assistant interpreter because it is a human right to receive medical care

that is equitable in all sense of their identity.

This technology solution to the societal problem surrounding science is one that,

after conversing with Hassan, began to take shape as a possible response to my second

initial hypothesis regarding how access and literacy are directly linked to large governing

bodies. It becomes more clear that it is less about the fault of the communities on whether

or not they actively seek out medical resources but, it is a reflection of institutions

shifting the burden onto them.

38

In connecting with Hassan and MAIN, I was not only able to get more insight into

how the healthcare system of Maine disadvantages the Somali Bantu community but, it

gave me even more context into the Western model of medicine.

A Field Analysis of the Somali Bantu Community Association

The Somali Bantu identity is a unique and complex one that the Somali Bantu

Community Association (SBCA) was founded to both celebrate and give the New

Mainers an outlet in which they could have full autonomy over the food they grow to

sustain and nourish their bodies. Farming, as Libah describes, is a pinnacle in the Somali

Bantu identity. Before they arrived in the United States, farming was essentially “life”. In

their home country, agriculture was the main source of sustainability for the Somali

Bantus. His response to the provided prompts was a combination of how medical

reconciliation with their agricultural identity has blossomed into an organization that

values community empowerment as a cornerstone of a holistic medical system. The

SBCA reclaims their narrative through land cultivation. When they faced discrimination

on a structural and military level, they were stripped of their ancestral lands. It was on

these lands that they grew crops, which nourished them and provided them a space for

community healing. After this was taken from them, they arrived in Maine where they

were met with further systemic violence. After the Somali Bantus arrived in Maine, they

faced both a lack of food and security. Those who qualified relied on food stamps and

39

community pantries to sustain their families. In terms of land ownership, there were often

retracted leasing offers that reflected the somewhat hostile response to their arrival. A

Yarmouth resident noted that, “Cultural differences, misunderstandings and

miscommunications” had sometimes prompted landlords to terminate the lease” (Lim 2).

However, regardless of intention, the Somali Bantu community was isolated from the

domestic community. However, Muhidin Libah had a vision that they would succeed in

their vision to gain land and rebuild their farming community. He founded Little Jubba

farms and the SBCA, which finally found stretches of agrarian green to begin their

cultivation of staple crops just in time for the spring bloom.

Their interesting contribution to the healthcare narrative about access is one that

truly builds from the ground up. The biggest access barriers to sustainable agricultural

health is a lack of land ownership. Recounting the emotion of being able to plant the first

seeds in the Maine soil following the SBCA’s founding, members reflected back on their

roots as farmers who lived and healed off the land. The impact of having the ability to

farm in Maine was enormous because it meant that the Somali Bantus would be able to

have a stake in their own health. Their story is one that speaks volumes about having

autonomy over one’s own health. In clinical settings where they are unfamiliar with

certain practices and procedures, having the ability to feed their body with food that they

have grown is a step towards medical reconciliation between the West and other cultures.

The SBCA’s narrative is very similar to the small seeds that they plant into the ground; it

grows long branches that stretch far into the soil around it. In creating a space where

40

health and wellness meet, future generations will be positively affected by the advocacy

done by those that came before them with a simple dream.

In addition to bridging access gaps with agricultural wellness, SBCA also provides

many different resources for preemptive health education. They address nutrition,

exercise, managing diabetes, information about prescription medications, and insurance

coverage through their medical reconciliation program. Their approach in combining

traditional Somali healing techniques and Western diagnoses is an interesting model that,

after my research, would be a fascinating potential medical education compromise.

Anew, there is an aspect of my research that directly correlates with the thesis’ two main

hypotheses. By interpreting health literacy through their own lens, the SBCA garners

health access by distributing their own healthcare narratives to better advocate for a more

inclusive system. They also take the burden that has been shifted onto them by the system

and create their own well of resources that can be accessed by Somali Bantus across

Maine and serve as that aforementioned holistic model to medical providers.

All in all, Muhidin Libah’s testament about his own creation was not only

enlightening but gave this thesis more depth in terms of the spectrum that healthcare

alternatives can have. The SBCA’s approach certainly echoed the points made by

MAIN’s push for more specialized healthcare workers and the importance of

incorporating identity into how health is viewed.

41

Conclusion

Intertwining scholarly literature and my own field work, my thesis was meant to

act as supplemental structuring for the Southern Somali community’s healthcare

narratives. In terms of my findings, it is clear that the established health literacy dilemma

stems from prejudicial structures within medicine. However, the problem does not simply

start and end with how providers are taught. It involves how marginalized communities,

such as the Somali Bantu communities are viewed in the scheme of health access and

literacy. A bulk of the burden concerning their lack of options is shouldered onto their

community. The organizations that I developed ties with are both instrumental to not only

addressing the systemic issues but provide their own identity-based solutions. The reality

is that because they are disadvantaged in the mainstream system, they are at risk for

developing health issues that are not properly treated. Within the Somali Bantu

community, some of the biggest health concerns were “health behaviors (22.7%),

diabetes (18.2%), and hypertension (14.4%), while those of the community were diabetes

(22.5%), hypertension (18.8%) and weight (15.9%)” (Mohamed et al. 458). These

conditions are all treatable, however, the lack of clarity from the health industry make it

difficult for this New Mainers generation to have a strong support system. The existing

barriers are due to medical school education failing to understand intersectional identities,

not following a community health worker- centered model for newly established

communities, and failing to acknowledge a medical reconciliation model that favors

cultural humility. Provided historical context, the Somali Bantus have been discriminated

42

against in their own country and experienced the same type of sentiments in the United

States. The contemporary Western healthcare model is complex and faceless. However, I

believe that it is possible to refrain from placing blame and giving the burden of

healthcare navigation. It is possible to embrace identity through healthcare and utilize

healthcare workers and agricultural advocates to ensure a more equitable future. To be

privy to the community narratives and have the ability to garner insight from community

organizations was extremely humbling. This thesis is an extension of the passion I have

for bettering healthcare and giving different communities the platform they deserve to

ensure a better tomorrow for their future generations.

43

Bibliography

1. Agrawal, Pooja, and Arjun Krishna Venkatesh. “Refugee Resettlement Patterns

and State-Level Health Care Insurance Access in the United States.” American

journal of public health vol. 106,4 (2016): 662-3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.303017

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4816078/

2. Anderson, Cynthia, Home Now: How 6,000 Refugees Transformed an American

Town (New York: Public Affairs, 2019).

3. Anderson, Warwick. “Teaching `Race' at Medical School.” Social Studies of

Science, vol. 38, no. 5, 2008, pp. 785–800.,

https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312708090798.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306312708090798

4. Bell, Susan E. "Interpreter assemblages: Caring for immigrant and refugee patients

in US hospitals." Social Science & Medicine. 226 (2019): 29-36.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.031. Epub 2019 Feb 26. PMID: 30831557.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30831557/

5. Besteman, Catherine, Making Refuge: Somali Bantu Refugees and Lewiston,

Maine (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016)

44

6. Caldwell, Josh; Metsch-Ampel, Dylan; and Moise, Isa, "Addressing Barriers for

New Mainers in Understanding and Utilizing Transportation Resources to Access

Medical Care and Finding Culturally Appropriate Solutions for the Barriers" .

Community Engaged Research Reports (2018). 60.

https://scarab.bates.edu/community_engaged_research/60

7. Carroll, Jennifer et al. “Caring for Somali women: implications for

clinician-patient communication.” Patient education and counseling vol. 66,3

(2007): 337-45. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.008

8. Cowenhoven, Julia Lane. "Educating Providers on the Value of Community Health

Outreach Workers in the New Mainer Population." University of Vermont Larner

College of Medicine. (2017).

https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1291&context=fmclerk

9. Fitzgerald, Hayley. “Barriers to mental health treatment for refugees in Maine: an

exploratory study.” Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices (2017).

https://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2969&context=theses

45

10. Hakim, Matteen, "Identifying Barriers to Healthcare Access for the Somali

Population at CMMC" (2016). Family Medicine Clerkship Student Projects.

11. Hassan, Mohammed. "Re: Hello from Colby College: Honors Thesis." Received

by Jordan McClintock, April 6, 2022.

12. Hill, Nancy, Emmy Hunt, and Kristiina Hyrkäs. “Somali Immigrant Women’s

Health Care Experiences and Beliefs Regarding Pregnancy and Birth in the United

States.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 23, no. 1 (January 2012): 72–81.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659611423828.

13. Houston, Ashley R., et al. “You Have to Pay to Live: Somali Young Adult

Experiences With the U.S. HealthCare System.” Qualitative Health Research, vol.

31, no. 10, Aug. 2021, pp. 1875–1889, doi:10.1177/10497323211010159.

14. Huisman, Kimberly A. Editor; Hough, Mazie Editor; Langellier, Kristin M. Editor;

and Nordstrom Toner, Carol Editor, "Somalis in Maine: Crossing Cultural

Currents" (2011). Faculty and Staff Monograph Publications. 48.

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/fac_monographs/48

46

15. Iftin, Abdi Nor, Call Me American (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing

Group, 2015)

16. Ineza, Darlene et al. “Barriers to Healthcare Access for New Mainers.” CORE.

(2019).

https://www.bowdoin.edu/news/2018/pdf/major-barriers-to-healthcare-access-for-

new-mainers-2-1.pdf

17. Jacoby, Susan D et al. “A Mixed-Methods Study of Immigrant Somali Women's

Health Literacy and Perinatal Experiences in Maine.” Journal of midwifery &

women's health vol. 60,5 (2015): 593-603. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12332

18. Khan, Shamaila. “Cultural Humility vs. Competence - and Why Providers Need

Both.” HealthCity, Boston Medical Center, 9 Mar. 2021,

https://healthcity.bmc.org/policy-and-industry/cultural-humility-vs-cultural-compe

tence-providers-need-both.

47

19. Langellier , Kristin M. “ICC 2006: 20th International Colloquium on

Communication - Applied Communication in Organizational and International

Contexts - Table of Contents.” Virginia Tech Scholarly Communication University

Libraries, Digital Library and Archives of the Virginia Tech University Libraries,

2006, https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ICC/2006/.

20. Libah, Muhidin. “Re: Hello From Colby College: Honors Thesis.” Received by

Jordan McClintock. April 4, 2022.

21. Liebman, A. et al. “Agricultural Health and Safety: Incorporating the Worker

Perspective”, Journal of Agromedicine, 15:3, 192-199, (2010), doi:

10.1080/1059924X.2010.486333

22. Lim, Audrea. ““We’re trying to re-create the lives we had”: the Somali migrants

who became Maine farmers”. The Guardian, 25 Feb 2021.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/feb/25/somali-farmers-maine

23. Maine Access Immigrant Network. “About Us.” MAIN,

https://main1.org/about.php.

48

24. Mohamed, Ahmed A et al. “An Assessment of Health Priorities Among a

Community Sample of Somali Adults.” Journal of immigrant and minority health

vol. 24,2 (2022): 455-460. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01166-y

25. Nelson, Alondra. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against

Medical Discrimination. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2013).

Print.

26. “Somali Bantu Community Association (SBCA).” Somali Bantu Community

Association, 2022. https://somalibantumaine.org/

27. Spitzer D L et al. “Towards inclusive migrant healthcare.” BMJ; 366 :l4256

(2019). doi:10.1136/bmj.l4256

https://www.bmj.com/content/366/bmj.l4256.abstract

28. Sun, Nina et al. “Human Rights and Digital Health Technologies.” Health and

human rights vol. 22,2 (2020): 21-32.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7762914/

49

29. Xin, Huaibo. "A Review of Refugees’ Access to Health Insurance in the USA."

Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices. 2018, 2: 119

https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100119

30. United States Department of Agriculture. “Farm Labor.” USDA ERS - Farm

Labor, 15 Mar. 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/.

50

Appendix A: Outreach Materials

Consent for Participation in Interview

I volunteer to participate in a research project for an honors thesis conducted by Jordan

McClintock from Colby College in the STS Department.

1. My participation in this project is voluntary. I have the freedom to exit the interview at

any time.

2. If I wish to remain completely anonymous: names, locations, and other details will be

changed to protect anonymity.

→ There will be no other person present in the interview apart from the

interviewer

→ Notes taken by the interviewer will never be shared

3. Participation will be approximately 45 minutes over Zoom or a phone call.

4. I understand that this research study has been reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Colby College.

51

5. I have read and understand the explanation provided to me. I have had all my questions

answered to my satisfaction, and I voluntarily agree to participate in this study.

Example Interview Questions

Non-for-profit organizations and advocacy groups

● Explain a little about what your organization does to support the Somali

community.

● What is the experience of a newly-arrived family or individual in terms of

obtaining physicals/general health check-ups?

● How have the communities of Southern Maine transitioned after the arrival of the

Somali community?

Healthcare Providers

● What does representation look like in terms of care providers that speak Somali?

● Describe the differences in obtaining clinical care within the Somali community

between someone with documentation and someone without.

● In your opinion, what type of sensitivity training (or anti-bias training) were you

given, if any, during your medical education or residency training.

Somali Community Representatives

52

● How easy it is to receive healthcare (ie: a doctor’s visit, walk-in, etc?)

● Difference in receiving care for documented vs. undocumented.

● Were healthcare resources explicitly outlined upon arrival to the US?

● Is there a discrepancy in healthcare for children- particularly displaced children

that have a sponsor but no legal guardian available?

53

Appendix B: Somali Healthcare Infographics

Figure 3. This Somali-translated infographic details COVID-19 safety protocols and vaccine resources.

https://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/View/30854/Image-COVID-19-Vaccine-60-Flyer-Somali

54

Figure 4. This infographic is a Somali-translated “Do’s and Don’ts” for those who have close contact with someone,

who has tested positive for COVID-19.

https://www.maine.gov/doe/sites/maine.gov.doe/files/inline-files/ENGLISH%20Dos%20and%20Donts%20Flyer.pn

g

55

Figure 5. This Somali-translated infographic is part of the the City of Portland Public Health Division’s Minority

Health Program regarding their COVID-19 vaccine initiative and key contacts.

https://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/View/31758/Vaccine-CHOW-Flyer-Somali?bidId=

56