“Not an Idea We Have to Shun”: Chinese Overseas

Basing Requirements in the 21

st

Century

by Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici

with Scott Devary and Jenny Lin

CHINA STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 7

Center for the Study of Chinese Military Aairs

Institute for National Strategic Studies

National Defense University

Institute for National Strategic Studies

National Defense University

The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National

Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes

the Center for Strategic Research and Center for the Study of Chinese

Military Affairs. The military and civilian analysts and staff who com-

prise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by perform-

ing research and analysis, publication, conferences, policy support,

and outreach.

The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary

of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified

Combatant Commands, to support the national strategic components of

the academic programs at NDU, and to perform outreach to other U.S.

Government agencies and to the broader national security community.

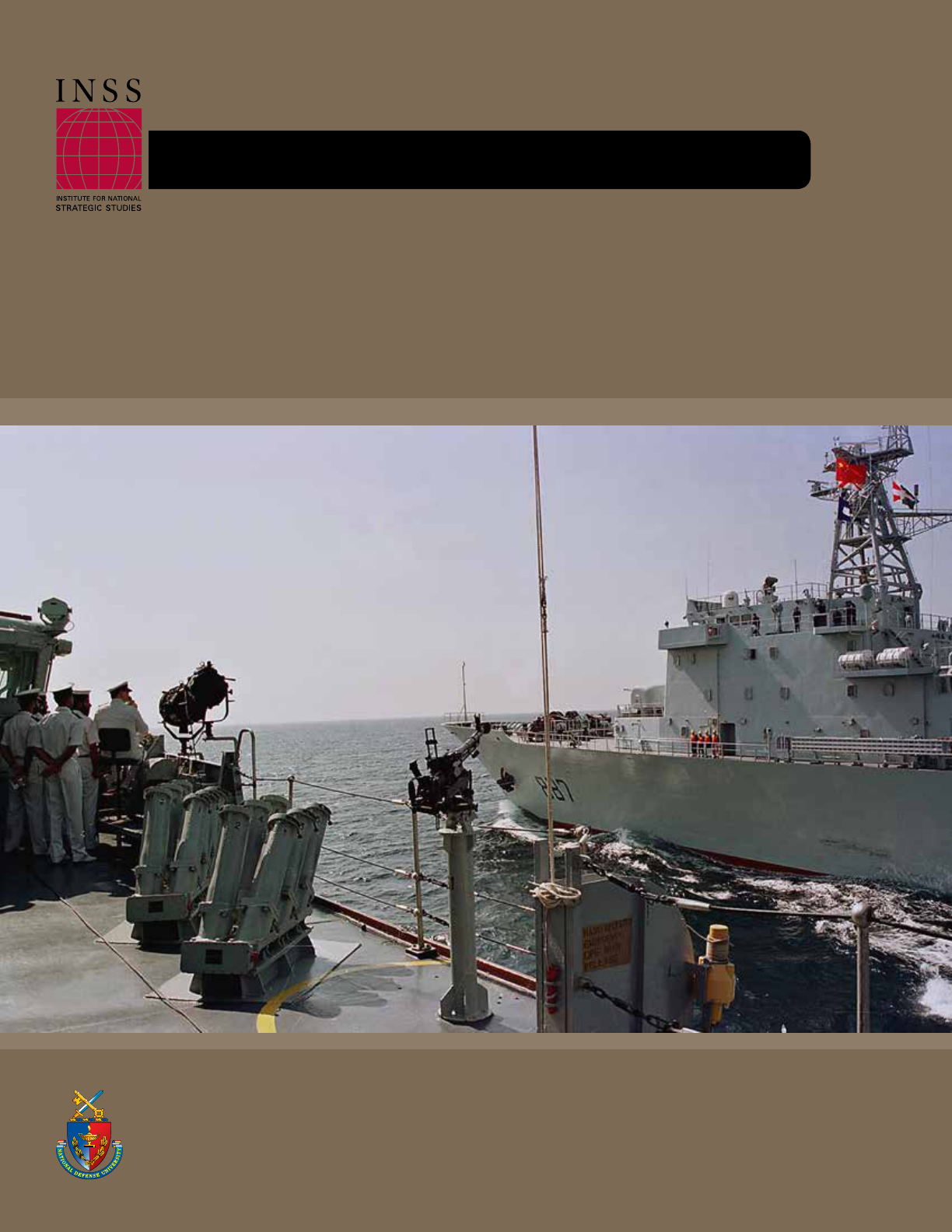

Cover photo: Pakistan and Chinese navy ships during joint maritime exercise

in Arabian Sea, November 24, 2005. Pakistan and China hold naval exercises,

particularly in nontraditional security fields to strengthen their defense

capability and enhance professional skills

(AP Photo/Inter Services Public Relations/HO)

“Not an Idea We Have to Shun”

Center for the Study of Chinese Military Aairs

Institute for National Strategic Studies

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Series Editor: Phillip C. Saunders

National Defense University Press

Washington, D.C.

October 2014

by Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici

with Scott Devary and Jenny Lin

“Not an Idea We Have to Shun”:

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

in the 21

st

Century

For current publications of the Institute for National Strategic Studies, please visit the NDU Press Web site at:

www.ndu.edu/press/index.html.

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those

of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any

other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited.

Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a

standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints

or reviews.

First printing, October 2014

Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 1

Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3

China’s Overseas Interests, Missions, and Likely Base and Facilities

Support Requirements ....................................................................................... 5

Six Alternate Models of Basing: e Deductive Approach ......................... 12

Dual Use Logistics Facility versus the String of Pearls:

e Inductive Approach ..................................................................................25

Could the String of Pearls Support Major Combat Operations? ...............33

Additional Considerations for a PLAN Logistics Base ...............................39

Conclusion and Policy Implications ..............................................................46

Appendix 1. “String of Pearls” Distance to Chinese Bases in

Nautical Miles ...................................................................................................50

Appendix 2. Required PLAN Force Structure for an Indian

Ocean Region Conict ....................................................................................51

Appendix 3. U.S. DOD Port Requirements Applied to Zhanjiang ............52

Appendix 4. Citizen and Netizen Public Opinion on

Overseas Basing ................................................................................................ 53

Notes .................................................................................................................. 54

About the Authors ............................................................................................61

1

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

Executive Summary

China’s expanding international economic interests are likely to generate increasing demands

for its navy, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), to operate out of area to protect Chinese

citizens, investments, and sea lines of communication. e frequency, intensity, type, and location

of such operations will determine the associated logistics support requirements, with distance

from China, size and duration, and combat intensity being especially important drivers.

How will the PLAN employ overseas bases and facilities to support these expanding

operational requirements? e assessment in this study is based on Chinese writings, com-

ments by Chinese military ocers and analysts, observations of PLAN operational patterns,

analysis of the overseas military logistics models other countries have employed, and inter-

views with military logisticians. China’s rapidly expanding international interests are likely

to produce a parallel expansion of PLAN operations, which would make the current PLAN

tactic, exclusive reliance on commercial port access, untenable due to cost and capacity fac-

tors. is would certainly be true if China contemplated engaging in higher intensity combat

operations.

is study considers six logistics models that might support expanded PLAN overseas

operations: the Pit Stop Model, Lean Colonial Model, Dual Use Logistics Facility, String of

Pearls Model, Warehouse Model, and Model USA. Each model is analyzed in terms of its abil-

ity to support likely future naval missions to advance China’s expanding overseas economic,

political, and security interests and in light of longstanding Chinese foreign policy principles.

is analysis concludes that the Dual Use Logistics Facility and String of Pearls models most

closely align with China’s foreign policy principles and expanding global interests.

To assess which alternative China is likely to pursue, the study reviews current PLAN

operational patterns in its Gulf of Aden counterpiracy operations

1

to assess whether the

PLAN is currently pursuing one model over the other and to provide clues about Chinese

motives and potential future trajectories. To ensure that this study does not suffer from

faulty assumptions, it also explicitly examines the strategic logic that Western analysts asso-

ciate with the String of Pearls Model in light of the naval forces and logistics infrastructure

that would be necessary to support PLAN major combat operations in the Indian Ocean.

Both the contrasting inductive and deductive analytic approaches support the conclusion

that China appears to be planning for a relatively modest set of missions to support its

overseas interests, not building a covert logistics infrastructure to fight the United States or

India in the Indian Ocean.

2

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Key ndings:

ere is little physical evidence that China is constructing bases in the Indian Ocean to

conduct major combat operations, to encircle India, or to dominate South Asia.

China’s current operational patterns of behavior do not support the String of Pearls

thesis. PLAN ships use dierent commercial ports for replenishment and liberty, and the

ports and forces involved could not conduct major combat operations.

China is unlikely to construct military facilities in the Indian Ocean to support major

combat operations there. Bases in South Asia would be vulnerable to air and missile at-

tack, the PLAN would require a much larger force structure to support this strategy, and

the distances between home ports in China and PLAN ships stationed at the String of

Pearls network of facilities along its sea lines of communication would make it dicult

to defend Chinese home waters and simultaneously conduct major combat operations in

the Indian Ocean.

e Dual Use Logistics Facility Model’s mixture of access to overseas commercial facili-

ties and a limited number of military bases most closely aligns with China’s future naval

mission requirements and will likely characterize its future arrangements.

Pakistan’s status as a trusted strategic partner whose interests are closely aligned with

China’s makes the country the most likely location for an overseas Chinese military base;

the port at Karachi would be better able to satisfy PLAN requirements than the new port

at Gwadar.

e most ecient means of supporting more robust People’s Liberation Army (PLA)

out of area military operations would be a limited network of facilities that distribute

functional responsibilities geographically (for example, one facility handling air logis-

tics support, one facility storing ordnance, another providing supplies for replenishment

ships).

A future overseas Chinese military base probably would be characterized by a light

footprint, with 100 to 500 military personnel conducting supply and logistics functions.

Such a facility would likely support both civilian and military operations, with Chinese

3

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

forces operating in a restrictive political and legal environment that might not include

permission to conduct combat operations.

Naval bases are much more likely than ground bases, but China might also seek to

establish bases that could store ordnance, repair and maintain equipment, and provide

medical/mortuary services to support future PLA ground force operations against terror-

ists and other nontraditional security threats in overseas areas such as Africa.

A more active PLA overseas presence would provide opportunities as well as challenges

for U.S.-China relations. Chinese operations in support of regional stability and to address

nontraditional security threats would not necessarily conict with U.S. interests and may

provide new opportunities for bilateral and multilateral cooperation with China.

Long-term access to overseas military facilities would increase China’s strategic gravity

and signicantly advance China’s political interests in the region where the facilities are

located. To the extent that U.S. and Chinese regional and global interests are not aligned,

the United States would need to continue to use its own military presence and diplomatic

eorts to solidify its regional interests.

A signicantly expanded Chinese military presence in the Indian Ocean would compli-

cate U.S. relations with China and with the countries of the region, compel U.S. naval and

military forces to operate in closer proximity with PLA forces, and increase competitive

dynamics in U.S.-China and China-Indian relations.

Finally, if some of the countries of the Indian Ocean region and elsewhere agree to host

PLA forces over the long term, their decision will imply a shi in their relations with the

United States, which may ultimately need to rethink how it engages and interacts with

these countries.

Introduction

is is the second report by the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Aairs assess-

ing the future trajectory of China’s out of area naval operations. A December 2010 report

used case studies of past Chinese operations, considered how other navies conducted out of

area operations, identied obstacles that all navies confronted in operating out of area, and

analyzed possible solutions the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) may undertake to

4

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

conduct out of area operations more eectively.

2

is report focuses on the logistics require-

ments for PLAN overseas operations in support of China’s expanding global interests and the

facilities and basing arrangements the PLAN might employ to support these missions over

the next 25 years.

This report is organized in five sections. The first section examines China’s expand-

ing international economic interests, which are likely to generate increasing demands for

the PLAN to operate out of area to protect Chinese citizens, investments, and sea lines of

communication (SLOCs). The second section establishes six alternative logistics and sup-

port models the PLAN could potentially use to support its expanded operations. It evalu-

ates each model against Chinese foreign policy and national security interests and then

considers its compatibility with established Chinese foreign policy principles. This section

employs a deductive approach: assessing China’s future overseas interests and likely mili-

tary operations and then identifying which basing/access arrangements would best support

those interests. The next section approaches the same issue with an inductive approach,

examining potential basing/access arrangements through the prism of Chinese activities in

the Indian Ocean and the operational patterns of Chinese military behavior in current out

of area operations.

e fourth section takes a closer look at the supposed strategic rationale for the String

of Pearls alternative and asks several questions: If China were intent on conducting major

combat operations in the Indian Ocean and elsewhere, what force structure and logistics in-

frastructure would be necessary? What indicators would be present if China were to embark

on this path? Are there indications that this is taking place? Would the Chinese consider this

a sound strategic option?

e h section draws on interviews with U.S. military logisticians and Chinese writings

to assess how China might implement logistics support arrangements that involve an overseas

logistics support base, including speculation about potential base sites.

e conclusion explores the strategic implications of the analysis. What do these ndings

suggest the United States should do with regard to its relationship with the other countries of

South Asia and the Indian Ocean region (IOR)? What do these ndings suggest about the future

of the U.S. relationship with China? What activities should the United States military engage in,

given the presence of Chinese military forces in facilities in the Indian Ocean and elsewhere?

What do the ndings of this report suggest about China’s future ambitions as a global or re-

gional military power?

5

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

China’s Overseas Interests, Missions, and Likely Base and Facilities

Support Requirements

Observers of Chinese foreign policy have long asserted that Chinese international eco-

nomic interests are expanding and that its foreign policy and security interests will inevitably

follow.

3

e growth in China’s global economic ties over the past decade has been dramatic.

e desire of foreign rms to tap inexpensive Chinese labor and access the Chinese market

produced a ow of foreign direct investment into China in the 1980s and 1990s, building new

production networks that integrated China into the regional and global economy. China’s

trade ties with both suppliers and markets grew rapidly as production of many goods relo-

cated to sites in China. Over the last decade, Chinese state-owned enterprises and private

companies have become signicant international actors in their own right, making interna-

tional investments to build factories and develop energy and mineral resources, acquiring

foreign rms, and building major infrastructure projects everywhere from Latin America to

Southeast Asia.

4

is activity has increased China’s overseas economic presence and made its

domestic growth—and thus its internal stability—dependent on the ability to access global

markets and resources.

From 2003 to 2014, Chinese foreign trade nearly quintupled, growing from $851 billion

to more than $4.16 trillion. China became a major exporter to developed country markets in

North America and Europe and also to developing countries in Africa, Latin America, and

the Middle East. At the same time, China began to import large volumes of oil and natural gas

(surpassing the United States as the world’s largest oil importer in September 2013).

5

e Chi-

nese economy also imported large quantities of minerals, metals, foodstus, and other natural

resources, becoming the most important driver of a global boom in commodity prices. Chinese

imports from resource-rich countries in Africa, Latin America, North America, and the Middle

East grew even faster than China’s overall trade, producing a new dependence on the mari-

time trade routes that connect China to regions outside Asia. In 2011, more than 60 percent of

China’s trade traveled by sea.

6

Trade is not the only dimension of China’s growing international presence. Chinese com-

panies have become major investors in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe. Ocial data

indicates that the cumulative total of Chinese outbound investment grew from approximately

$33.2 billion in 2003 to more than $531.9 billion in 2012. Chinese government data shows that

as of 2012, Chinese companies had invested more than $21.7 billion in Africa, $68.2 billion

in Latin America, and $25.5 billion in North America.

7

e Heritage Foundation/American

6

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Enterprise Institute “China Global Investment Tracker,” which captures the nal destination

of Chinese investment with more precision than ocial government data, shows even higher

totals of Chinese investment outside Asia.

8

While Chinese foreign direct investment in overseas factories, mines, and energy projects

is an important and growing national interest, it also involves a signicant increase in Chinese

expatriates living and working abroad, particularly in the developing countries of sub-Saharan

Africa. Erica Downs of the Brookings Institution testied in April 2011 that:

[t]he expansion of Chinese companies around the world has increased the

number of Chinese citizens working overseas, including in countries with elevated

levels of political risk. e number of Chinese working abroad is estimated to

have increased from 3.5 million in 2005 to 5.5 million today. is has prompted

China’s foreign policy establishment to step up its eorts to ensure the safety of

Chinese citizens overseas.

9

In addition to the 5.5 million Chinese citizens working abroad, more than 60 million

travel overseas every year. Protecting these citizens—or evacuating them if the political or

security environment becomes unstable—has become an increasingly important and politi-

cally sensitive task for the Chinese government. Mathieu Duchâtel and Bates Gill note that

between 2006 and 2010, “a total of 6000 Chinese citizens were evacuated from upheavals in

Chad, Haiti, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Solomon Islands, ailand, Timor-Leste and Tonga.” In

2011 alone, “China evacuated a staggering 48,000 of its citizens from Egypt, Libya and Ja-

p a n .”

10

Both PLA Navy and PLA Air Force (PLAAF) units deployed to assist in the evacuation

of Chinese citizens from Libya.

ese trends are likely to continue, albeit at a slower pace, as the Chinese government tries

to rebalance the Chinese economy to rely more on domestic consumption to drive economic

growth. China’s dependence on imported food, minerals, metals, and especially energy will also

continue to deepen. China currently imports about 6.2 million barrels of oil a day, mostly from

the Middle East and Africa. is gure is projected to rise to 13 million barrels a day by 2035.

11

Despite government eorts to improve energy eciency and diversify supplies of oil and natu-

ral gas, a recent study by the State Council’s Development Research Center concluded that by

2030, China might import 75 percent of its oil and that dependence on overseas natural gas will

also rise rapidly. e director of the center warned that “rising risk for the energy transporta-

tion routes will pose new challenges which will be directly aected by geopolitical risks in the

7

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

neighboring regions, the Middle East and Africa.”

12

China is constructing oil and natural gas

pipelines from Kazakhstan, Russia, and Burma to mitigate some potential transport risks, but

it will remain heavily dependent on seaborne oil and liqueed natural gas supplies from the

Middle East and Africa. Andrew Erickson and Gabriel Collins conclude, “In the end, pipelines

are not likely to increase Chinese oil import security in quantitative terms, because the addi-

tional volumes they bring in will be overwhelmed by China’s demand growth; the country’s net

reliance on seaborne oil imports will grow over time, pipelines notwithstanding.”

13

Expanding Interests, Expanding Missions

Chinese civilian leaders have called upon the PLA to play a greater role in protecting Chi-

na’s overseas interests. en–General Secretary Hu Jintao used a 2004 speech to the Central

Military Commission to give the PLA four “New Historic Missions.” Daniel Hartnett summa-

rized them: “to ensure military support for continued Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule

in Beijing; to defend China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and national security; to protect

China’s expanding national interests; and to help ensure a peaceful global environment and

promote mutual development.”

14

e third mission gives the PLA new responsibilities to help

protect China’s overseas economic, political, and security interests. Examples include PLAN

participation in counterpiracy missions in the Gulf of Aden since 2008 and PLAN and PLAAF

eorts to evacuate People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizens from Libya in 2011.

Chinese ocers and scholars have begun writing openly about how expanding interests

abroad require a greater PLA role to protect those overseas interests and recommending that the

Chinese leadership consider establishing bases overseas. Retired PLAAF Colonel Dai Xu writes:

China is the world’s number-one or number-two importer of crude oil and

mineral markets. At the same time, China is a major exporter of textiles, toys,

and other goods. is import-export trade is primarily dependent upon maritime

transport, yet these sea routes are full of incredibly perilous factors. . . . Looking

at the example of the Middle East, which supplies over half of China’s oil imports,

Chinese oil transport vessels traveling from that region must pass through the

Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca, and the South China Sea.

Danger is everywhere in the Persian Gulf, pirates run amok on the Indian Ocean,

and the navies of India and the United States eye our vessels jealously. e power

of various countries crisscrosses the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea,

and pirates also hunt these areas.

15

8

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

He goes on to note:

[a]nother aspect is that, following the growth of China’s foreign exchange reserves

and the expansion of foreign investment, the amount of Chinese-held xed assets

overseas will become increasingly larger. Incidents in recent years of Chinese oil

workers being kidnapped in Africa and facilities being raided have also sounded

the security alarm. erefore, when selecting locations for overseas bases, in

addition to the needs of escorting and peacekeeping, one must also consider the

long-term protection of overseas interests.

16

East China Normal University Professor Shen Dingli argues that the Chinese public ex-

pects the government to protect overseas interests and furthermore, he argues that the issue of

an overseas base need not be considered taboo: “[Setting up overseas military bases is not an

idea we have to shun; on the contrary, it is our right. . . . As long as the bases are set up in line

with international laws and regulations, they are legal ones. . . . ere are four responsibili-

ties: the protection of the people and fortunes overseas; the guarantee of smooth trading; the

prevention of the overseas intervention which harms the unity of the country; and the defense

against foreign invasion.”

17

Shen also highlights the utility of overseas bases in protecting these

interests, including potential threats against Chinese SLOCs:

When the public discusses overseas military bases they refer to the supply base

for the navy escorting the ships cruising in the Gulf of Aden and Somalia. e

discussion shows people’s enthusiasm in defending the interests of the country.

Yet their worries are not the most important reasons for the set up of an overseas

military base. It is true that we are facing the threat posed by terrorism, but

dierent from America, it is not a critical issue. e real threat to us is not posed

by the pirates but by the countries which block our trade route.

18

The vulnerability caused by China’s increasing dependence on imported oil is of par-

ticular interest to Chinese strategists. As James Mulvenon writes, “It is no surprise that

PLA strategists would view China’s dependence on USN [United States Navy] protection

of critical SLOCs as a source of frustration and motivation and would therefore seek to

develop an independent means of securing key energy supply routes.”

19

Mulvenon notes

that this does not necessarily suggest that China will develop a full-fledged blue water navy

9

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

to protect its SLOCs unilaterally. Beijing could devise a mixture of strategies and policies

including diplomacy, maritime cooperation with countries in the IOR, and enhanced naval

capabilities.

20

A debate is under way about how China should meet the challenge of protect-

ing overseas interests.

Expanded Missions for the People’s Liberation Army Navy

China’s expanding international economic interests are almost certain to generate increas-

ing demands for the PLAN to operate out of area to protect Chinese citizens, investments,

Expanded Chinese Interest Potential Corresponding PLA Missions

Protection of citizens living abroad Noncombatant evacuation operations,

humanitarian assistance/disaster relief,

counterterrorism, counterinsurgency,

training and building partner capacity,

special operations ashore, riverine

operations, military criminal investigation

functions, military diplomacy

Protection of Chinese property/assets Counterterrorism, counterinsurgency,

humanitarian assistance/disaster relief,

training and building partner capacity,

special operations ashore, military criminal

investigation, physical security/force

protection, riverine operations, military

diplomacy, presence operations

Protection of Chinese shipping against

pirates and other nontraditional threats

Counterpiracy, escort shipping, maritime

intercept operations, training and building

partner capacity, sector patrolling, special

operations ashore, visit, board, search and

seizure, replenishment at sea, seaborne

logistics, military diplomacy

Protection of sea lines of communication

against adversary states

Anti-submarine warfare, anti-air warfare,

anti-surface warfare, carrier operations,

escort shipping, maritime intercept

operations, air operations o ships,

helicopter operations, vertical replenishment,

replenishment at sea, seaborne logistics

operations, military diplomacy, mine

countermeasures

Table 1. Notional PLA Missions to Protect Chinese Overseas Interests

10

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

and SLOCs. Such tasks could include protection of PRC citizens living and working abroad,

of Chinese property or assets on foreign soil, of Chinese shipping from pirates and other non-

traditional security threats, and of SLOCs against hostile adversary states. e PLAN could be

assigned specic missions to protect those interests (see table 1).

e frequency, intensity, type, and location of operations will determine the military forces

necessary and the associated logistics support requirements, with distance from China, size

and duration of operations, and combat intensity being especially important drivers of logistics

support requirements. Most of these missions would not require PLAN forces to conduct com-

bat operations against adversary states. Accordingly, they have less demanding logistic support

requirements, with distance, size, and duration of operations being the main drivers. ese less

intensive missions are listed in the rst three rows of table 1 displayed above.

However, some missions (listed in the fourth row of table 1) necessary for the protection of

Chinese SLOCs against adversary states would require the PLAN to be prepared for high-inten-

sity conict against a modern military in waters far from China. is type of combat operations

would impose additional logistic support requirements, including large hospital and healthcare

facilities; ordnance storage and distribution; petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL) storage and

distribution; mortuary services; large ship and equipment repair facilities; air trac control;

and other air support facilities and operations.

Historically, such combat operations are best supported by well-developed bases in the vi-

cinity of the operational area. Sustaining the large naval forces needed to conduct major combat

operations against a major state in the Indian Ocean would require a sizable logistics support

infrastructure. Ships get damaged in combat, so the PLAN would need large and numerous

shipyard facilities to repair them. It is possible that the Chinese have a dierent operations

and strategic concept in mind if they are contemplating a major conventional conict with

India—possibly a short, sharp attack intended to shock the Indians into compliance. Nonethe-

less, two historic data points appear to belie this argument. First, the Chinese are aware of the

importance of logistics support and infrastructure for major conventional conicts such as the

Second World War.

21

During that conict, the United States established hundreds of shipyards

throughout the Asia-Pacic to support the war eort. A considerable amount of writing on this

subject emphasizes the importance of strategic rear areas, transportation support, and supply-

ing front lines.

22

Second, lessons taken from the Falklands/Malvinas conict have made the

Chinese intimately aware that even limited wars can impose a heavy logistical burden on com-

batants operating out of area.

23

11

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

Major combat operations typically also produce large numbers of casualties, which would

require sizeable hospital facilities in mainland China and in a forward location to treat critically

and seriously wounded soldiers and sailors. e United States relies on forward medical facili-

ties to stabilize seriously wounded soldiers before transport and also on large hospital facilities

in Europe to care for wounded personnel from Iraq and Afghanistan before sending them to the

continental United States (CONUS) for additional treatment at Walter Reed National Military

Medical Center.

e PLAN would need ordnance resupply, given the high ammunition expenditure rates

in major combat operations.

24

Ordnance could be transported from depots in China on am-

munition ships, but these ships would be vulnerable to submarine and air attacks (as happened

with Japan during its Pacic War with the United States). A country cannot rely entirely on air

or sea transport over long distances to resupply units engaged in combat. Militaries typically

store some ordnance in forward armories so it can be easily accessible and dispensed to combat

units. e long distance from China to the Indian Ocean means the PLAN would need an over-

seas base to store ordnance, especially for submarines and ships with vertical launch tubes that

cannot be reloaded at sea.

25

In addition, the PLAN would need access to petroleum, oil, other lubricants, and other

replenishments to operate away from home ports for long periods. During peacetime, these

stocks are available from commercial port facilities. However, during a conict, the laws of war

and customary requirements for neutrality prohibit port facilities or bases in neutral countries

from providing support to combatants.

26

If such a facility were supplying PLAN forces, it would

no longer be considered neutral and therefore would be subject to attack by China’s adversaries.

Finally, any military bases and logistics facilities providing support for PLAN combat op-

erations would require protection from air and missile attack. As the history of conventional

military conicts attests, from World War II to the Gulf War, if China was facing a country such

as India with signicant military capabilities, the PLA would need air bases to provide air cover

for naval forces and to defend bases and logistics facilities from attack. e PLA would also

want surface-to-air missiles with some ballistic and cruise missile defense capability to protect

air bases, naval bases, and logistics facilities from air and missile attack. is all adds up to a

substantial military footprint within the territory of a third-party host country.

e bottom line is that if China wants military dominance in the Indian Ocean (which

implies the ability to ght and win major combat operations), it would need a much larger

navy and a logistics and support infrastructure that far exceeds current capabilities. Even if we

12

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

posited the possibility of Chinese use of covert munitions storage and secret wartime access

agreements,

27

it would be insucient for sustained combat operations.

Some evidence suggests that even if its international missions do not expand, the PLAN is

already having diculty supporting current missions due to limitations in the available logistics

infrastructure. ese operational limitations are likely to eventually lead the Politburo Standing

Committee and the Central Military Commission to authorize the establishment of some kind

of overseas PLA facility. Retired PLAN Rear Admiral Yin Zhuo is an outspoken advocate for

overseas bases. Not long aer the initial Gulf of Aden deployment in October 2008, he insisted

that China consider establishing an overseas base to ease the logistical and supply strain on

PLAN forces.

28

He noted that multiple 3-month deployments aected PLAN morale and ability

to maintain readiness.

29

Yin also pointed out that diculties Chinese sailors confronted in out

of area deployments (such as lack of fresh fruits, vegetables, and potable water, problems com-

municating directly with Beijing, and lack of medical care) would be resolved if Beijing would

allow the PLAN to establish an overseas base near its forward operations.

30

en–PLA Chief of General Sta Chen Bingde also highlighted obstacles the PLAN faces

while conducting out of area operations. In a May 2011 speech at the National Defense Uni-

versity in Washington, DC, General Chen noted that continued Gulf of Aden counterpiracy

deployments would strain the PLAN and “give China great diculty.”

31

Chen also stated that

China plans to continue these deployments because the missions protect its national interests

abroad.

32

e PLAN’s operational diculties in performing current out of area operations, the

likely increase in demand for such operations in the future, and other factors such as Chinese

public support for overseas bases (see appendix 4) suggest that the PLAN cannot rely inde-

nitely on commercial facilities alone to support its overseas operations.

Six Alternative Models of Basing: e Deductive Approach

is report explores six possible overseas logistics support models that Chinese civilian

and military leaders may consider to support expanded overseas operations: the Pit Stop Model,

Lean Colonial Model, Dual Use Logistics Facility, String of Pearls Model, Warehouse Model,

and Model USA. Each is dened and discussed below.

e Pit Stop Model. One option is to continue the current PLAN practice of using com-

mercial port facilities to compensate for the lack of overseas bases. Some Chinese scholars and

military analysts advocate continued use of commercial ports as “pit stops” to provide basic

services such as refueling, provisioning, electrical power, and waste disposal for PLAN surface

vessels.

33

One article noted that “[s]uch arrangements are basically a commercial undertaking,

13

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

but must be negotiated government-to-government because military forces are involved. Many

nations have such arrangements in the region, particularly the Persian Gulf. Chinese sailors

coming ashore would basically be treated like tourists, and subject to local law.”

34

Some PLAN ocers appear content with current ad hoc arrangements supporting the Gulf

of Aden deployments.

35

Zhang Deshun, then-PLAN Deputy Chief of Sta, stated in 2010, “[w]e

have no agenda to set up military establishments” and no need to establish overseas bases.

36

Senior

Captain Yan Baojian, a South China Sea Fleet commander, indicated that the navy could operate

overseas and conduct out of area missions without any bases on foreign soil: “e naval force can

work extensively with China’s business operations worldwide for military supplies, in addition to

[obtaining materiel from] advanced supply ships.”

37

In a 2010 article, retired Rear Admiral Zhang

Zhaozhong noted that the commercial use of regular supply points for rest and entertainment,

food and water, ship and equipment maintenance, and medical treatment should suce.

38

Zhang

argued both the international community and host nations would welcome these kinds of activi-

ties because the supply stops support United Nations–mandated missions, and the PLAN boosts

the local economy by spending money at commercial facilities.

e Lean Colonial Model. e Lean Colonial network involves specialized bases scattered

throughout the world to support colonies. Nations that utilized this model in the 19

th

and 20

th

centuries did so to support broader economic and foreign policy objectives rather than to proj-

ect military power. e model utilizes bases within sailing distance of each other but lacking

any fortications or defenses against seaborne attack. e Lean Colonial Model can advance

national commercial interests but cannot support a naval presence strong enough to preserve

sovereignty when challenged.

Germany’s Pacic colonies, which at one time stretched from mainland China to just north

of Australia and New Zealand, illustrate the Lean Colonial Model. With the exception of the

Qingdao port in China, German colonial possessions were initially established by trading com-

panies acting without government support.

39

Germany supported these colonies nancially, but

they were viewed primarily as a source of national pride and prestige.

40

German colonies devel-

oped ports and logistics centers to support commercial operations but did not invest in defen-

sive fortications or infrastructure to support naval operations. Although equipped with nine

ships, the German Asiatic Squadron’s forays from its homeport in Qingdao were infrequent and

ill supplied.

41

e squadron’s logistics network was based on contracts with private companies,

which greatly limited its operational capacity and range in the event of a conict.

42

e Ger-

man Navy planned to use the squadron to harass British and American ships in the Pacic and

to prevent a shiing of assets to the Atlantic rather than to defend German colonies. Within

14

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

months aer the outbreak of World War I, every German colony in the Pacic was under the

control of Australia, New Zealand, or Japan.

Dual Use Logistics Facility. Some Chinese analysts and PLA ocers argue that an overseas

base would provide improved logistics and supply support to out of area PLAN ships and task

forces at lower cost and with greater capability than commercial facilities. e overseas base would

be equipped with medical facilities, refrigerated storage space for fresh vegetables and fruit, rest

and recreation sites, a communications station, and ship repair facilities to perform minor to in-

termediate repair and maintenance. In a 2010 interview, retired Rear Admiral Yin Zhou argued

that “a relatively stable, relatively solid base for re-supply and repair would be appropriate” to

support Chinese ships conducting antipiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. “Such a base would

provide a steady source of fresh fruit, vegetables and water, along with facilities for communica-

tions, ship repair, rest and recreation, and medical evacuation of injured personnel.”

43

Dai Xu, a former PLA Air Force colonel, argued in 2009 that China “needs to have power

adequate to protect world peace before it will be able to eectively shoulder its international

responsibilities and develop a good image. e fulllment of this duty requires a specic supply

facility for the provision of support.”

44

Dai argued that escorting and peacekeeping missions will

become regular PLAN missions: “How to execute these tasks in ever wider sea areas with even

lower costs and over longer periods of time is bound to become a practical issue that will have

to be dealt with by strategic decision-making departments.”

45

Military analyst Liu Zhongmin

echoes these themes: “[H]ow China will develop its overseas bases is a question that we can no

longer avoid answering. . . . Since China began to send navy convoys on anti-piracy missions to

the Gulf of Aden and the Somali coast in 2008, the lack of overseas bases has emerged as a major

impediment to the Chinese navy’s cruising eciency.”

46

e String of Pearls Model. e String of Pearls concept emerged from a 2004 Booz Al-

len Hamilton (BAH) study, “Energy Futures in Asia: Final Report.” e authors argued that if

China needed to protect its ow of energy through the Indian Ocean, it could build on its ex-

isting commercial and security relationships to establish a string of military facilities in South

Asia. At the time, press reports suggested China had contributed to construction of naval bases

in Burma, funded construction of a new port in Gwadar, Pakistan, and invested in commercial

port facilities in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. e speculative analysis in the BAH study has come

to be accepted in some Indian and U.S. policy circles as a description of China’s actual strategy

for its out of area activities.

Considered narrowly as a logistics model, the main dierence between the Dual Use Logis-

tics Facility and String of Pearls models lies in the potential for Chinese commercial investments

15

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

in port facilities to support higher intensity military and combat operations. Construction of

commercial port infrastructure could serve as cover for construction of secret munitions stock-

piles and other port infrastructure that could support combat operations. Chinese commercial

ties with host countries could potentially translate into secret agreements to allow PLAN access

to the facilities in a conict. Finally, Chinese investments in commercial port facilities (and the

resulting expansion in Chinese political inuence in host countries) might allow commercial

ports to be transformed into full-edged Chinese military bases at some point in the future.

e November 2004 BAH report marks the rst analytic reference to a so-called Chi-

nese String of Pearls strategy. e authors were asked to address the question: “If China were

confronted with a vulnerable source of energy supplies and the possibility of the United States

cutting o China’s source of energy supplies through its superior navy, what possible strategies

would the Chinese pursue and do we see any evidence that this is taking place?” e Booz Al-

len team did not extensively research Chinese sources to determine Chinese perspectives, but it

engaged in educated speculation on strategic responses China might pursue if confronted with

a “Malacca Dilemma”

47

worst-case scenario. e term String of Pearls originated with “uniden-

tied participants of a workshop conducted to support this project.”

48

e report submitted to the Oce of Net Assessment devotes only two pages to the String

of Pearls concept. In a section entitled “Sealane Strategy,” the authors note that Chinese activi-

ties in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Cambodia, and the South China Sea suggest that “China is

building strategic relationships along the sealanes from the Middle East to the South China Sea

in ways that suggest defensive and oensive positioning to protect China’s energy interests but

also serve its broader security objectives.” e report states:

participants at the Energy Futures in Asia workshop referred to this set of strategic

relationships along the sealanes as China’s ‘String of Pearls.’ . . . ese relationships,

which have been developing for years, could serve multiple strategic objectives for

the Chinese. For example, bolstering its presence in Myanmar and Pakistan hems

in India and simultaneously positioning [sic] China to address the vulnerability

to its seaborne oil shipments with either defensive or oensive tactics. A sealane

strategy positions China to take a more oensive approach to securing its energy

resources by threatening to raise the risk premium for other energy consumers.

Using its strategic positioning along the sealanes, China could pursue a deterrence

strategy if it believed that its energy ows were in danger of being interdicted or

threatened by the United States or others.

16

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Such a deterrence strategy “would entail posing a credible threat to any ship in the seal-

anes, thereby creating a climate of uncertainty about the safety of all ships on the high seas.

Whether or not China will have the capacity to pose a credible threat is uncertain and a point

of debate; China would require both robust military capabilities and permission from the host

countries to allow it to undertake oensive operations from their territories.” e report in-

cluded a map labeled “China’s Activities Along the Sealanes” that “highlights Gwadar and Pasni,

Pakistan; three locations in Myanmar; the potential location of a Kra Canal in ailand; Woody

and Hainan Island in the South China Sea.”

Other defense analysts subsequently adopted the term “String of Pearls,” oen treating

it as a description of China’s actual strategy rather than speculative analysis. For example,

the author of a 2006 report titled “String of Pearls: Meeting the Challenge of China’s Rising

Power Across the Asian Littoral” published by the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Studies

Institute asserted:

Each “pearl” in the “String of Pearls” is a nexus of Chinese geopolitical inuence

or military presence. Hainan Island, with recently upgraded military facilities, is a

“pearl.” An upgraded airstrip on Woody Island, located in the Paracel archipelago

300 nautical miles east of Vietnam, is a “pearl.” A container shipping facility in

Chittagong, Bangladesh, is a “pearl.” Construction of a deep water port in Sittwe,

Myanmar, is a “pearl,” as is the construction of a navy base in Gwadar, Pakistan.

Port and aireld construction projects, diplomatic ties, and force modernization

form the essence of China’s “String of Pearls.” e “pearls” extend from the coast

of mainland China through the littorals of the South China Sea, the Strait of

Malacca, across the Indian Ocean, and on to the littorals of the Arabian Sea and

Persian Gulf.

49

e report argued that Chinese eorts to establish a presence in the Indian Ocean are a response

to concerns about access to energy shipments from the Persian Gulf:

To sustain economic growth, China must rely increasingly upon external sources

of energy and raw materials. Sea lanes of communication (SLOC) are vitally

important because most of China’s foreign trade is conducted by sea, and China

has had little success in developing reliable oil or gas pipelines from Russia or

Central Asia. Since energy provides the foundation of the economy, China’s

17

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

economic policy depends on the success of its energy policy. Securing SLOCs for

energy and raw materials supports China’s energy policy and is the principal

motivation behind the “String of Pearls.”

50

Considered in terms of logistics and military capability, the String of Pearls Model would

oer some advantages. It could be less costly than a dedicated network of overseas military

bases, since commercial investments in port infrastructure would generate some economic re-

turns that military bases would not. Commercial investments are less likely to provoke negative

international reactions than military bases or base access agreements. is model could also

potentially oer a stepping stone toward a future network of dedicated military bases, with

commercial investments helping to build the political relationships necessary for countries to

provide China with base access or permit Chinese bases on their territory.

e String of Pearls Model would have signicant operational drawbacks as well. Com-

mercial port facilities would not oer ammunition storage, prepositioned spare parts for mili-

tary vessels, or maintenance specialists. ey would provide less operational security and be

vulnerable to attack in event of a conict. Even if China were able to covertly preposition mili-

tary supplies or negotiate secret base access agreements with host countries, Beijing would like-

ly have diculty securing permission to use such bases to support combat operations against

major countries. Some of these operational drawbacks could be overcome by improvements

in facilities and port security, but beyond a certain point such improvements would transform

commercial “pearls” into overt Chinese military bases.

Warehouse Model. e Warehouse Model developed by the British between the two world

wars demonstrates a h potential way for a naval power to maintain a eet far from home.

Aer considering their economic situation and war plans, the British decided a few defensible

ports with large oil supplies and fully capable repair facilities were the best method to support

naval operations in the Far East. e Royal Navy decided to stockpile oil at its naval base in

Singapore rather than upgrading the coal-based infrastructure at smaller ports or investing in a

costly tanker procurement program.

51

Singapore was supplied with all the necessary stores and

dock facilities to act as the base of operations for the Far East Fleet. Ports west of Singapore were

never adequately updated to support major eet operations.

52

e Royal Navy relied entirely on

oil stores within its main ports. In 1921, the British did not operate a single oil tanker east of the

Suez Canal.

53

Singapore was chosen due to its location protecting the main SLOC to India and

because it was more defensible than alternatives such as Hong Kong. It was expected to be able

to hold out for 3 months against superior Japanese forces until reinforcements could arrive from

continued on page 20

18

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Broader Interpretations of the “String of Pearls”

e meaning of the term String of Pearls has broadened over time to go well

beyond a speculative description of how China might use commercial investments to sup-

port naval operations in the Indian Ocean. Some analysts now use the term to refer to any

Chinese blue water navy capability developments, any activity the Chinese navy has taken

part in outside of the Asia-Pacic Region (for example, the PLAN’s Gulf of Aden deploy-

ments), and any eorts China may undertake to ensure continued access to oil and raw

materials coming from Africa and the Middle East.

Some assessments assign motives that go far beyond concerns about access to

energy and raw materials. One assessment argues: “e ‘String of Pearls’ strategy . . .

provides a forward presence for China along the sea lines of communication that now

anchor China directly to the Middle East. e question both the United States and India

have is whether this strategy is intended purely to cement supply lines and trade routes, or

whether China will later use these in a bid for regional supremacy.”

1

Other assessments, especially from Indian think tanks and defense organizations,

state unequivocally that the objective of China’s String of Pearls strategy is to dominate

the Indian Ocean region. Consider this analysis from the Indian Army’s Centre of Land

Warfare Studies:

China’s strategy to acquire port facilities for its navy in Pakistan,

Myanmar, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, is well known and has been called

China’s “string of pearls” policy by western analysts. Beijing’s game plan

appears to be to isolate India and dominate the SLOCs from the Indian

Ocean to the South China Sea. Notwithstanding that Beijing is actively

pursuing initiatives to tie down India in its neighborhood, it lodged

protests in May 2006 over a new “quadrilateral” initiative held in Manila

between the U.S., Japan, India and Australia.

2

e String of Pearls concept has shaped how many analysts think about China’s

activities in South Asia and the potential for the PLA Navy to operate overseas. A Google

search for China and String of Pearls results in almost 300,000 hits. e Congressional

Research Service’s periodic assessment of Chinese naval capabilities specically mentions

19

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

the String of Pearls concept as a possible future path for Chinese military operations.

3

e String of Pearls was also mentioned in the Department of Defense’s Joint Operating

Environment 2008, which includes a map entitled “e String of Pearls: Chinese political

inuence or military presence astride oil routes.” e map is of China, the Indian Ocean,

and the Persian Gulf with areas in South Asia demarcated as potential “pearls.”

4

Supporters of a more expansive String of Pearls concept argue that China’s invest-

ment and construction of both commercial and military sites in South Asia and broader

development of strategic relations in the region are designed to:

assure access to energy supplies and raw materials coming in from the Middle East

and the Persian Gulf

exert Chinese political inuence in the Indian Ocean region

encircle, dominate, or hem in India

militarily dominate the Indian Ocean region

deter the United States, India, or other powers in South Asia from interdicting

Chinese shipping coming from the Persian Gulf.

1

Chris Devonshire-Ellis, “China’s String of Pearls Strategy,” in China Brieng.com, March

18, 2009, available at<www.china-brieng.com/news/2009/03/18/china%E2%80%99s-string-of –

pearls-strategy>.

2

Gurmeet Kanwal and Monika Chansoria, “Breathing Fire: China’s Aggressive Tactical

Posturing,” Centre for Land Warfare Studies Issue Brief no. 12, October 2009, 5.

3

Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implication for U.S. Navy Capabilities—

Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service report RL33153, October 17,

2012, 43.

4

As found in e Joint Operating Environment 2008: Challenges and Implications for the

Future Joint Force (Norfolk, VA: U.S. Joint Forces Command, November 25, 2008), available at

<www.scribd.com/doc/10537915.joe-2008>.

20

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Europe. Britain had two smaller bases located closer to Japan, both of which relied on Singapore

as a logistics center.

e Royal Navy’s Logistical Model—a few very large bases intended to provide “one stop

shopping”—directly led to its naval diculties during World War II. ese ports established

British control over critical sea lines of communication, but the vast distances between them

made reinforcement extremely dicult during the initial stages of a conict. e Royal Navy re-

lied too heavily on Singapore and subsidiary bases and neglected the procurement and elding

of the necessary eet auxiliaries and support ships for aoat logistics and replenishment at sea.

54

When the British war plan failed and Singapore was captured, other British bases could not be

utilized eectively because they were too distant from intended operational areas or lacked the

necessary infrastructure.

55

Furthermore, once one of these mega bases fell, the lack of interme-

diate logistic centers made staging an oensive operation exceedingly dicult.

e Warehouse Model does have a few distinct advantages. e largest is its low interna-

tional prole; relying on only a few well-equipped and dispersed bases limits the number of

reliable allies needed and reduces the political ramications of basing troops abroad. is was

not a problem for Imperial Britain, but it was a serious consideration for the Soviets, who built

a similar naval infrastructure during the Cold War using ports in Egypt, Somalia, and its satel-

lite countries. A second advantage is cost. It is cheaper to build and maintain a few major bases

than to develop and maintain a global network of well-equipped bases. Finally, large bases can

have defensive capabilities and, if successfully defended, provide an excellent in-theater staging

point for oensive operations.

Model USA. International experts consider the U.S. logistics model the most successful meth-

od to maintain large-scale military operations abroad. e terrestrial network combines large bases

with minor bases/port access agreements to support U.S. naval and air forces and allow for exible

resupply. In addition to established infrastructure, the U.S. Navy currently maintains the largest aux-

iliary ship eet in the world. e result is unprecedented capabilities to resupply ships while under-

way and to support prolonged ground operations from the sea. In addition to more than 30 naval

bases and naval support facilities, the U.S. Military Seali Command has 110 active service ships

supporting eet operations.

56

e United States currently maintains a signicant base operations

network in every major ocean and sea and thus possesses a logistics system that can support opera-

tions anywhere in the world. e large auxiliary eet means that the loss of any single base or even a

series of bases does not automatically reduce the Navy’s operating range or capacity.

e U.S. response to the tsunami that struck the IOR on December 26, 2004, demonstrates

the logistic system’s exibility. Immediately aer the tsunami struck, the U.S. Air Force quickly

21

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

mobilized to create a forward logistics base in ailand some 8,000 miles from CONUS.

57

e

Air Force transported approximately 24.5 million pounds of supplies over 47 days.

58

e Navy

also contributed greatly to the relief eort. By January 1, 2005, the USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN

72) Carrier Strike Group was providing logistical support, along with a Marine Expeditionary

Unit that arrived on January 4.

59

A U.S. Navy hospital ship sailed from San Diego and arrived

in waters near Aceh within 2 weeks of the disaster. Forty-nine percent of the xed wing aircra,

55 percent of the helicopters, and 25 percent of the ships used in the humanitarian relief eort

were of U.S. origin.

is exible logistics system allows the U.S. military to surge troops, supplies, and logistics

support quickly and to support operations far from CONUS because it maintains logistics hubs

scattered throughout the world. Yet the U.S. logistics model derives its strength mainly from its

large auxiliary eet and airli capacity. e sheer number of platforms and amount of li capac-

ity support a wide variety of operations far from U.S. soil.

One major shortcoming of the U.S. logistics model is the high cost of building and main-

taining large and complex bases, ports, and ships, making it economically infeasible for less

auent countries. Maintaining a geographically distributed and extensive system of bases also

requires immense diplomatic and political capital. Finally, countries that choose to pursue such

an extensive and capable logistics network may raise international concerns about potential

interventionist ambitions. From a purely military perspective, however, the American logistics

model is unrivaled in terms of capability.

e Chinese Foreign and Defense Policy Interest Framework

Which logistics model is China most likely to adopt to support its expanding international

interests? Table 2 examines each model against criteria important to Chinese foreign and de-

fense policy interests to assess the likelihood that Beijing will pursue a particular model.

Three of the six logistics support models do not satisfy China’s broad foreign policy

interests as enunciated by Beijing throughout its history of foreign relations. The Lean

Colonial, Warehouse, and USA models all violate two of China’s most important foreign

policy principles: noninterference in the internal affairs of other countries and not acting

like an imperialist or hegemonic power. The Lean Colonial Model is simply not applicable

to a postcolonial world of sovereign states. Given China’s self-image as a champion of the

developing world and a positive alternative to other global powers, it is highly unlikely to

pursue models that involve large overseas military bases or extensive networks of facilities

on the sovereign territory of other states. Beyond the rationale that China is unlikely to

22

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

Pit Stop Lean

Colonial

Dual Use

Logistics

Facility

String of

Pearls

Warehouse Model

USA

Does not

threaten China’s

“peaceful rise”

image

Ye s No Ye s Ye s No No

Does not pose

a risk to China’s

relationship with

host nation

Ye s Ye s Ye s Yes No No

Neighboring

countries will not

feel threatened

Ye s Ye s Ye s Yes No No

Helps China

address a wide

range of military

contingencies

No No Ye s Ye s Ye s Ye s

Helps China

protect its

overseas

economic

interests

No No Ye s Ye s Ye s Ye s

Relatively

inexpensive

No Yes No No No No

Satises

expectations of

ordinary Chinese

citizens

No No Ye s Ye s Ye s Ye s

Does not

generate

excessive friction

with the United

States

Ye s Ye s Ye s Yes/No No No

Protected against

external attack

No No No No Ye s Ye s

Does not require

large amounts of

transportation

assets

Ye s Ye s No No Ye s No

Table 2. Assessments of Chinese Logistics Models and International Interests

23

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

violate foreign policy principles that it has established as a foundation for its foreign and

defense policy behavior, there is an even stronger reason that China will not establish these

kinds of overseas bases. They would threaten China’s image as a peaceful rising power and

could imperil China’s future economic growth, if the international community interprets

such bases as evidence of malign Chinese long-term intentions.

In contrast, the Pit Stop Model closely conforms to China’s foreign policy principles. How-

ever, for reasons discussed below, this model is unlikely to support China’s national security

interests over the long term.

Does the Pit Stop Model Serve Chinese Long-Term Security Interests?

Today’s limited out of area PLA operations are consistent with Chinese foreign policy and

national security interests. China’s policy species that it will not set up military bases in other

countries. Ocial policy states that China does not take part in operations far from China’s

shores except at the invitation of a host country or when mandated by an international organi-

zation like the United Nations. China’s ocial overseas basing policy is consistent with eorts

to portray China’s rise as “peaceful” to the international community. Even given these policy

limitations, the PLAN has been able to conduct Gulf of Aden counterpiracy operations success-

fully since late 2008.

e Gulf of Aden deployment demonstrates that the Chinese military remains at the very

nascent stages of out of area combat operations.

60

For now, the PLAN appears to be content to

remain at this stage of low-intensity combat naval force development, which can be supported

using only commercial facilities (albeit at a higher cost than other logistics models).

An earlier NDU study on China’s out of area naval operations argued that most great pow-

ers follow a path of increasingly demanding out of area operations.

61

If China follows this path,

it will eventually participate in maritime intercept operations, engage in combat with pirates in

the high seas, and continue to escort shipping through pirate-infested waters. China is likely

to conduct freedom of navigation operations to keep its sea lines of communication open and

could potentially engage in major combat operations to defend or seize disputed territories in

the South and East China Seas or to protect natural resources associated with disputed maritime

territory. China might also have to conduct SLOC protection operations if an Indian Ocean

state such as India decides to threaten Chinese shipping with air, surface, and subsurface forces.

Some Chinese government ocials and military ocers recognize the need to resolve the pi-

racy problem on land, implying that the government could eventually employ special forces or

other military assets to deal with that problem.

62

24

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

All of these missions imply the use of PLA forces to engage in combat with pirates, ter-

rorists, insurgents, and potentially other states. However, there are a number of reasons why a

logistics support model that depends solely on commercial facilities cannot support combat

operations that result in signicant loss of materiel and manpower.

First, a country cannot assure access to commercial facilities during times of conict.

63

For

example, during the Civil and Spanish-American wars, Hong Kong and Japan would not allow

the U.S. Asiatic Squadron to access commercial port facilities. Second, commercial facilities do

not have the capability to support severely damaged warships, mortuary services for soldiers

killed in action, and medical attention for large numbers of wounded service members. Severely

damaged warships can sometimes be repaired in foreign commercial shipyards, but this could

be extremely expensive in the absence of a special arrangement with the host country, and a re-

quest could be denied due to political considerations. Even if commercial facilities agree to per-

form these operations, supporting the PLA Navy would not necessarily be their top priority if

other commercial opportunities are more lucrative or the costs of abrogating existing contracts

are too high. China cannot assume that foreign commercial port facilities would act against

their own commercial interests to support China during a regional conict.

High Costs of the Pit Stop Model

e high costs associated with an exclusively commercial logistics network will pressure

China to pursue a dierent model, especially if the scope and intensity of PLA Navy out of area

operations increase over time. Conversations with PLA ocers indicate that using commercial

ports to support the Gulf of Aden deployments has been extremely costly and time-consuming.

en-PLA Chief of General Sta General Chen Bingde indicated in May 2011 that the PLA has

encountered operational diculties in sustaining the Gulf of Aden deployment. Chen did not

explicitly cite cost, but this was likely one factor.

64

U.S. Navy logisticians suggest relying solely on commercial facilities can prove extremely

costly, especially in wartime. Experts point out that even in operations short of war, there is a

direct relationship between conict intensity and the need for security at ports and other fa-

cilities.

65

Necessary security features might include patrol boats to monitor and patrol harbors;

divers to check for saboteurs below the water line; erection of jersey barriers and other fences

around the piers serving the ships; and additional security personnel monitoring the gates.

66

A

commercial facility depends on costly private contractors or its own personnel to perform these

services. A military facility can perform these functions more eciently with military person-

nel. Ship and military equipment repair can also be extremely costly. Although a commercial

25

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

facility can repair ships damaged in low-intensity combat, these repair services would be ex-

tremely expensive.

67

e Pit Stop Model is unlikely to remain a viable logistics alternative if the

intensity of Chinese military out of area operations increases in parallel with China’s expanding

global economic, political, and security interests.

e Dual Use Logistics Facility and the String of Pearls: Two Viable Options

This analysis suggests that the Dual Use Logistics Facility and String of Pearls logistics

models are most consistent with China’s longstanding foreign policy principles and can

best support China’s expanding overseas economic and security interests. The third sec-

tion of the study examines the ability of the two models to support the most likely PLAN

operations over the next 20 years; the fourth section examines whether the String of Pearls

Model could support higher intensity combat operations as part of a long-term effort to

dominate the IOR.

Dual Use Logistics Facility versus the String of Pearls: e Inductive

Approach

e Dual Use Logistics Facility and the String of Pearls models both appear compatible

with Chinese foreign policy principles and with China’s long-term overseas interests. Both

models would involve the PLA using a mix of commercial and military facilities to project

power farther from China’s shores. China would need to develop close political and strategic

ties with at least some host nations to gain greater access to their commercial and military facili-

ties. Both models would support increased out of area operations to protect China’s expanding

overseas economic, political, and security interests.

e two models dier in two important respects (other than the site of the bases). First, the

Dual Use Logistics Facility Model is not tied to port access in specic countries, while the String

of Pearls Model requires China to have good political relations with numerous host countries.

e so-called pearls are all associated with specic facilities in specic countries that can be

examined. Second, the String of Pearls Model can potentially provide greater logistics support

for military and combat operations if overt commercial access arrangements are supplemented

with covert prepositioning of munitions and military supplies and secret diplomatic agreements

for base access in the event of a conict.

If China intends mainly to combat nontraditional threats and develop a modest power pro-

jection capability to respond to a relatively small-scale overseas contingency, such as a noncomba-

tant evacuation operation (NEO), humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) missions,

26

China Strategic Perspectives, No. 7

low-intensity conict, counterterrorism, or protection of PRC expatriates, the Dual Use Logistics

Facility is sucient. China could use dual use facilities as forward operating logistics platforms

to engage in nontraditional security operations (including special forces operations ashore) to

combat terrorists and other threats to China’s overseas operations and citizens. However, if China

seeks the capability to conduct major combat operations in the Indian Ocean, the String of Pearls

Model is more plausible.

is section explores the ability of these two models to support the most likely PLAN op-

erations in the Indian Ocean (excluding major combat operations) by examining the physical

characteristics of sites supposedly associated with the String of Pearls and studying the patterns

of current PLAN operational behavior overseas. e potential ability of the String of Pearls

Model to support the force structure China would need to dominate the Indian Ocean is ex-

plored in the next section.

Examining the Physical Evidence for the String of Pearls

In recent years, authors have started to look more critically at the physical evidence for

the existence of a Chinese “String of Pearls.” One assessment addressed persistent rumors that

China has built or is building military bases in Burma. Veteran Burma watcher William Ashton

wrote in 1997:

For all the reports on this subject which have appeared . . . few appear to draw

on rm evidence or can be traced to reliable sources. Many seem to be based

on rumours, speculation or even deliberate misinformation. ere has also

been considerable confusion over particular places, developments and military

capabilities, which has then been recycled by journalists and academics in

subsequent articles.

68

In a 2007 article, “Burma, China and the Myth of Military Bases,” Andrew Selth writes, “It

seems to have escaped the notice of most observers that at no stage had the existence of a large

Chinese SIGINT [signals intelligence] station on Great Coco Island been ocially conrmed

by any government other than India’s, which was hardly an objective observer. is includes

the U.S., which has both an interest in China’s activities in the Indian Ocean and the means to

detect them.”

69

Aer an in-depth examination of Great Coco Island and Hainggyi Island, both

reportedly candidates for China’s String of Pearls, Selth found no physical evidence of a military

facility on these islands:

27

Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements

Great Coco Island has no sheltered harbor or facilities capable of handling a

ship of any size. ere was only a small pier there until 2002, when the berthing

facilities on the island were reportedly expanded. e airstrip, while apparently

extended some time aer 1988, was also vulnerable to the region’s poor weather.

Similarly, neither the hydrography nor the topography of Hainggyi Island lent

themselves to the construction of a maritime facility of any size.

70