159159

5

c h a p t e r

This chapter investigates whether fiscal policy should

be used to combat business cycle fluctuations, especially

downturns. Can discretionary fiscal policy successfully

stimulate output? Or does it do more harm than good?

New evidence presented here, from emerging as well as

advanced economies, indicates that the effects of fiscal

stimulus can be positive, albeit modest. But policymak-

ers must be very careful about how stimulus pack-

ages are implemented, ensuring that they are timely

and that they are not likely to become entrenched and

raise concerns about debt sustainability. The chapter

concludes with a discussion of how automatic stabiliz-

ers could be made more effective and how governance

improvements could reduce “debt bias” concerns related

to discretionary actions.

I

n recent months, as economies have been

buffeted by falling asset prices, rising costs

for raw materials and credit, and waning

confidence, there have been renewed calls

for governments to actively use fiscal policy to

support efforts taken by central banks to prevent

sharp declines in activity. Once again, there is a

lively debate about the appropriate role of fiscal

policy in managing the business cycle, especially

during a downturn: Are discretionary fiscal

actions helpful, or do they sometimes do more

harm than good? When is a discretionary pack-

age most effective? When is it better simply to

let automatic stabilizers do the job?

The debate over the appropriate role of fis-

cal policy in managing the business cycle has

persisted for many years. One school of thought

argues that taxes, transfers, and spending can

be used judiciously to lean against fluctuations

in economic activity, especially to the extent that

economic fluctuations are mainly due to mar-

kets falling out of equilibrium instead of react-

ing to changes in fundamental factors such as

productivity. Others contend that fiscal policy

actions are generally either ineffective or make

things worse, because the actions are ill timed

or they create damaging distortions. This latter

point of view has dominated the debate over the

past two decades; consequently, fiscal policy has

taken a backseat to monetary policy. But there

also has been a recognition that there are times

when monetary policy needs the support of fis

-

cal stimulus, such as when nominal interest rates

approach zero or the channels of monetary

policy transmission are in some way impeded.

Against this background, this chapter takes

a fresh look at the role of fiscal policy during

economic downturns. The main objectives are

to (1) analyze how fiscal policy has typically

responded during downturns; (2) examine the

effects on economic activity of fiscal stimulus

during downturns; (3) identify the main fac-

tors that affect the outcomes of fiscal policy

interventions; and (4) offer policy suggestions,

in light of both empirical evidence and insights

from theoretical work, on (a) whether and when

to use discretionary fiscal policy, (b) the implica

-

tions of using various fiscal policy instruments,

and (c) the appropriate balance between auto-

matic stabilizers and discretionary actions.

This chapter seeks to contribute to the con-

siderable literature on fiscal policy as a counter-

cyclical tool in three ways. First, it specifically

evaluates whether discretionary fiscal policy

responses to downturns have been timely and

temporary. Second, whereas most previous

studies have focused on the effects of policy in

advanced economies, this chapter also looks

at evidence for emerging economies. Finally,

the chapter complements the empirical analy-

sis with simulation analysis designed to assess

how fiscal multipliers depend on the choice of

The main authors of this chapter are Alasdair Scott

(team leader), Steven Barnett, Mark De Broeck, Anna

Ivanova, Daehaeng Kim, Michael Kumhof, Douglas

Laxton, Daniel Leigh, Sven Jari Stehn, and Steven

Symansky, with support from Elaine Hensle, Annette

Kyobe, Susanna Mursula, and Ben Sutton.

FISCAL POLICY AS A COUNTERCYCLICAL TOOL

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

160

fiscal instruments and the characteristics of the

economy.

The policy record shows that discretionary

fiscal policy has been more timely than some

critiques suggest. But there are valid concerns

about whether fiscal stimulus packages will be

temporary and the implications for the path

of government debt. Empirical evidence sug-

gests that discretionary fiscal stimulus has a

moderately positive effect on output growth

in advanced economies. However, the effects

appear to be constrained in emerging econo-

mies. This might be because of credibility

issues, especially debt concerns. Simulation

experiments show that fiscal multipliers can

vary considerably, depending on the instrument

used, the degree of monetary policy accom-

modation, and the type of economy. Consistent

with the empirical evidence, increases in interest

rate risk premiums as a result of debt concerns

can render fiscal multipliers negative, suggesting

that discretionary fiscal stimulus may do more

harm than good.

Does this mean there is no role for counter-

cyclical fiscal policy? In practice, the extent of

automatic stabilizers has been related to the size

of government, but more extensive government

is generally associated with lower growth. Given

this dichotomy, it is worth investigating further

whether countercyclical fiscal rules and the fiscal

policy framework can be designed to increase

the ability of fiscal policy to smooth fluctua-

tions in output and income over the course of

business cycles—without increasing the size of

government or placing debt stability at risk.

The chapter is organized as follows. The next

section provides a brief review of the empirical

and theoretical literature on the role of fiscal

policy in stabilizing output. The following two

sections present, first, the results of new empiri-

cal work that characterizes how fiscal policy

has been used in both advanced and emerging

economies and then an analysis of its effects.

The subsequent section uses formal simula-

tion-based analysis to examine the effectiveness

of various stimulus options and the effects of

various macroeconomic factors when the policy

is implemented. The concluding section offers

some policy suggestions.

Understanding the Fiscal Policy Debate

Fiscal policy can work in two general ways to

stabilize the business cycle. One way is through

automatic stabilizers, which arise from parts of

the fiscal system that naturally vary with changes

in economic activity—for example, as output

falls, tax revenues also fall and unemployment

payments rise.

1

Discretionary fiscal policy, on the

other hand, involves active changes in policies

that affect government expenditures, taxes, and

transfers and are often undertaken for reasons

other than stabilization.

By their nature, automatic stabilizers play an

immediate role during downturns. But they are

usually by-products of other fiscal policy objec-

tives. As such, the size of automatic stabilizers

tends to be associated with the size of govern-

ment (see, for example, Fatás and Mihov, 2001),

suggesting that an increase in the size of govern-

ment can help dampen output volatility (see

Galí, 1994). However, many argue that a larger

government acts as a drag on growth over the

longer term. Hence, there is a potential con-

flict between increasing stability and increasing

economic efficiency. Moreover, the effectiveness

of automatic stabilizers may be more a matter of

proper design than size.

Because automatic stabilizers are often limited

in scope—Box 5.1 reviews the extent of auto-

matic stabilizers across economies—the active

use of discretionary fiscal measures is often

promoted as a countercyclical tool. Skeptics,

however, question governments’ ability to deliver

well-timed measures as well as the macroeco-

nomic effects of discretionary fiscal measures

and the longer-term implications for fiscal

sustainability.

1

Hence, the strength of automatic stabilizers depends

on the size of transfers (such as the scope of unemploy-

ment insurance), the progressivity of the tax system, and

the effects of taxes and transfers on labor participation

and demand for workers and capital.

161

How important are automatic stabilizers?

This box looks at their quantitative impact

on the fiscal balance, especially in compari-

son with discretionary fiscal policy. First, the

impact of automatic stabilizers on the primary

balance varies across countries. The volatil-

ity in the primary balance is more a result of

changes in discretionary policy than of auto-

matic stabilizers. However, for many countries,

changes in discretionary policy are not well

synchronized with the business cycle, suggest-

ing that automatic stabilizers are often a more

important source of systematic countercyclical

policy actions.

Automatic stabilizers are measured using

the change in the cyclical balances estimated

in the event analysis in the main text of this

chapter.

1

The impact of automatic stabiliz-

ers on fiscal outcomes varies across countries

and is positively related to both government

size and output volatility. Government size is a

good proxy for the size of automatic stabilizers,

and provides the horizontal axis in the first

figure.

2

Realized volatility in the cyclical bal-

ance—measured as the standard deviation of

the change in the cyclical balance—is roughly

equal to government size times the volatil-

ity in the output gap. The first figure shows

that even though emerging economies have

smaller governments, they tend to experience

higher volatility in the cyclical balance than

advanced economies. This is largely because

emerging economies have more volatile output

gaps. However, looking separately at emerging

economies and advanced economies (to control

for the higher output volatility in emerging

economies), there is a positive relationship

between government size and cyclical bal-

ance volatility—that is, countries with larger

The main author of this box is Steven Barnett.

1

The elasticity-based measure is used for the analysis

in this box. The sample period is 1992–2007.

2

Balassone and Kumar (2007), Box 4.2, explains

why this holds. This general finding is robust to

income elasticity assumptions.

automatic stabilizers have more variation in the

cyclical balance.

3

Changes in discretionary fiscal policy,

however, account for more of the volatility of

primary balances than automatic stabilizers. On

average, the volatility of the cyclically adjusted

balance is about three times greater than that

of the cyclical balance. This is true for advanced

economies and for emerging economies. But

the extent to which these policy changes play a

countercyclical role depends on how well they

are synchronized with the business cycle. To

examine this empirically, a measure of the cycli-

cality of fiscal policy discretion is compared with

3

Government size, however, is often found to

be negatively correlated with output volatility (for

example, Andrés, Doménech, and Fatás, 2008), which

would dampen the otherwise mechanical positive

relationship between government size and cyclical

balance volatility.

Box 5.1. Differences in the Extent of Automatic Stabilizers and Their Relationship with

Discretionary Fiscal Policy

understanding the Fiscal Policy debate

10 20 30 40 50 60

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

Volatility in Cyclical Balance

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Standard deviation of change in cyclical balance

Government size (percent of GDP)

Emerging economies

Advanced economies

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

162

the size of automatic stabilizers.

4

The second fig-

ure shows that discretionary fiscal policy tends

to be more countercyclical in advanced econo-

mies (when the countercyclicality of discretion

is greater than zero), but is often procyclical in

emerging economies (below zero). The units

on the two axes are comparable and indicate

the percentage point change in the respective

balance (after dividing by 100) for a 1 percent

-

age point increase in the output gap. If a coun-

try lies above the 45-degree line, it indicates that

discretionary policy makes overall fiscal policy

more countercyclical than automatic stabilizers

4

Cyclicality of fiscal policy is measured by a regres-

sion, run in first differences, with the cyclically

adjusted primary balance as the dependent variable

and the output gap as the explanatory one. A positive

coefficient indicates a more countercyclical policy.

This regression, however, is potentially problematic in

that it ignores the relationship (endogeneity) between

fiscal policy and the output gap.

do. As can be seen, this happens in only a few

cases, including some of the Anglophone coun-

tries with smaller governments, as well as some

of the Nordic ones with larger governments.

However, there is little systematic evidence that

countries with smaller governments compensate

for weaker automatic stabilizers by using more

discretion.

Together, these findings would suggest that

(1) automatic stabilizers have, in general,

played a more consistently countercyclical role

than discretionary fiscal policy, and (2) changes

in discretionary fiscal policy are either poorly

timed or related to factors other than output

stabilization. A caveat, however, is that fiscal

policy discretion is measured by the cyclically

adjusted balance, which, as discussed in the

main text, is an imperfect proxy, because it may

also capture factors unrelated to discretionary

changes, notably asset price fluctuations.

Asset price movements directly affect

financial transaction and capital gains taxes,

but they also have broader, indirect revenue

implications, notably through a wealth effect

on consumption. To the extent that these

movements do not fully track the business

cycle (for example, amplified fluctuations rela-

tive to those of the output gap), the revenue

effects will not be captured by conventional

tax revenue elasticities and will be part of the

cyclically adjusted component of revenue. In

an unpublished study, the IMF staff prepared

econometric estimates of the short-run sen-

sitivity of cyclically adjusted tax revenue to

house and equity price fluctuations in the G7

countries. The cyclically adjusted revenue data

are computed using the conventional adjust-

ment methods, ensuring consistency of the

results. The estimates suggest that a 1 percent

decline in both house and equity prices could

reduce total tax revenue by up to almost 1

percent, with the house price decline account-

ing for most of the drop. The estimates also

indicate that Canada, Japan, the United King-

dom, and the United States are more sensitive

to house and equity price fluctuations than

the continental European G7.

Box 5.1 (concluded)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

-100

-50

0

50

100

Cyclicality of Structural Balance

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Cyclicality of discretion

Government size (percent of GDP)

Emerging economies

Advanced economies

163

These skeptics argue that discretionary fiscal

measures cannot be delivered quickly enough

by legislatures, especially compared with the

speed with which a central bank can change

its policy rate. Hence, there is a risk that fiscal

stimulus will arrive just as the economy recovers

from a downturn. Moreover, argue the critics,

fiscal stimulus measures are not likely to be well

targeted, but are likely instead to be directed

to wasteful and distortionary public spending

and revenue measures more responsive to the

pressures of interest groups than the needs of

the economy. Furthermore, they are not likely

to be withdrawn sufficiently quickly to pre-

serve fiscal sustainability. For instance, there is

widespread evidence that fiscal policy in emerg-

ing and less developed economies is procyclical

rather than countercyclical, in part because of

political incentives to run larger deficits in good

times, when financing is available (Talvi and

Végh, 2000).

Even if fiscal stimulus can be delivered

quickly, does that justify the use of discretionary

fiscal policy? There is still considerable debate

and little theoretical consensus. A textbook

Keynesian position is that private consumption

and investment are driven by current income,

with the implication that output is highly

responsive to changes in fiscal policy. But fiscal

policy can be much less effective in an open

economy, depending on the degree of capital

mobility and the exchange rate regime, because

fiscal stimulus might simply “leak out.” In addi-

tion to the standard crowding-out arguments,

many neoclassical theorists emphasize the role

of expectations about future income and taxes,

arguing that fiscal multipliers are likely to be

small because forward-looking households will

figure out that temporary fiscal stimulus mat

-

ters little to their lifetime income; multipliers

may even be negative, if increased government

expenditures lead to offsetting reductions in

private consumption and investment.

2

By con-

2

For example, the well-known Ricardian equivalence

critique of Barro (1974) argues that households and

firms understand that deficits accompanied by future tax

trast, recent work using so-called New Keynesian

models argues that an increase in government

consumption still can have positive consump-

tion and real wage effects, if there are nominal

and real rigidities and liquidity constraints (see,

for example, Galí, 2006). These models also

suggest that not all temporary fiscal measures

are ineffective: policies that affect the incentive

to switch the timing of consumption—such as

changes in consumption taxes—are likely to be

most effective when they are understood to be

temporary rather than permanent.

In recent years, four factors may have become

increasingly relevant:

•

The extent of market rigidities: Rigidities in goods

and labor markets may have decreased over

time, as a result of microeconomic reforms,

and access to credit may have become more

widely available, reducing fiscal multipliers.

•

The monetary policy framework: The impact of

fiscal policy can be expected to increase if it

is accommodated by monetary policy, thus

alleviating the crowding-out effect.

•

Globalization and openness: To the extent that

economies are more integrated—that is, an

increasing share of domestic demand falls on

imported goods—discretionary fiscal policy

will be less effective today than previously.

•

Financial innovation: Deregulation of finan-

cial markets and increased access to global

capital may have eased credit constraints on

households and firms, with the implication

that consumption and investment are less con-

strained by current income and less respon-

sive to discretionary fiscal policy measures.

However, cross-border financial integration

can also reduce the sensitivity of interest rates

to government borrowing and ease crowding-

out effects.

Unfortunately, empirical work has not settled

the theoretical debates. Estimates of fiscal multi-

rises leave them no better off in net present value terms,

and therefore they save rather than spend temporary

(lump-sum) tax cuts. Neoclassical models often exhibit

negative wealth effects following increases in govern-

ment spending that are strong enough to reduce private

consumption and investment.

how has discretionary Fiscal Policy tyPically resPonded?

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

164

Perhaps surprisingly, the empirical literature

on the effects of fiscal policy does not provide a

clear answer to the simple question of whether

discretionary fiscal policy can successfully

stimulate the economy during downturns. Esti-

mates of the effects of fiscal policy on many key

macroeconomic variables can differ not merely

in degree but in sign. This box aims to show

why demonstrating conclusively what happens as

a result of discretionary fiscal policy is, in fact,

extremely difficult.

Any empirical work on this issue faces the

following problems: (1) Every assessment of

the impact of a policy change must take into

account the economic circumstances when the

policy was implemented. (2) A fiscal stimulus

can be achieved by many different combina-

tions of taxes, transfers, and spending, each of

which can have different effects. (3) There will

sometimes be a difference between the date on

which a change in fiscal policy is measured from

the data and the date on which the policy was

common knowledge to households and firms.

(4) Policy measures and economic activity are

both endogenous—they depend on each other

at the same time—and so it is not immediately

clear what determines what just by looking

at simple correlations. This last problem is

arguably the most difficult to overcome. The

researcher must somehow strip out those parts

of changes in taxes, transfers, and spending that

occur passively (such as from automatic stabiliz-

ers) from those that represent the true policy

initiative, and use that measure of fiscal impulse

to determine the effects on economic activity.

To illustrate, suppose overall fiscal policy, g,

evolves according to

g = (a + b)y + h, (1)

where y is the output gap. For simplicity, one

can think of g as representing only government

expenditures, so that a stimulus occurs when

g is positive. There are two reactions of fiscal

policy to the state of the economy: an automatic

component, represented by a, and a system-

atic discretionary component, represented by

b. Unexpected discretionary fiscal policy is

denoted by h.

Now suppose that the output process is

y = dg + ε, (2)

where d is the fiscal multiplier and ε repre-

sents shocks independent of policy. There are

two significant problems presented by this

system. First, we have a classic simultaneity

problem—attempting to assess the effects of

fiscal policy on output by estimating (1) will

result in biased estimates. The second prob-

lem is a measurement problem—the difficulty

of distinguishing systematic discretionary

policy changes from automatic stabilizers. The

elasticity-based fiscal impulse measure can be

thought of as using OECD estimates of a and

constructing

f

~

= f – ay.

Estimating the cyclicality of this measure is

equivalent to estimating the parameter b.

1,2

When examining the effectiveness of fiscal

policy in the regression framework, a fiscal

impulse measure that mistakenly includes cycli-

cal changes generated by automatic stabilizers

will lead to invalid inferences about the effects

of discretionary fiscal policy. The second fiscal

impulse measure therefore focuses entirely

on h, the effects of unexpected fiscal policy

shocks.

3

Other approaches in the literature attempt

to address the same issues. Structural vector

autoregressions (SVARs) use statistical criteria

to estimate shocks to fiscal policy and measure

1

See also Galí and Perotti (2003) for an application

of the same method.

2

When looking at the reaction of fiscal policy in

emerging economies, it is necessary to make the

“zero-one” assumption of income elasticities of expen-

ditures and revenues, which is a cruder approach to

measuring a but conceptually the same.

3

For precise details on how the fiscal impulse mea-

sures are constructed, see Appendix 5.1.

Box 5.2. Why Is It So Hard to Determine the Effects of Fiscal Stimulus?

The main author of this box is Alasdair Scott.

165

how has discretionary Fiscal Policy tyPically resPonded?

how well those shocks can explain movements

in output that are not accounted for by other

economic shocks. Three problems are poten-

tially relevant. As with reduced-form regressions,

statistical assumptions need to be made to iden-

tify the fiscal shocks. Second, most VARs ignore

the importance of debt dynamics in condition-

ing responses (whether or not a temporary rise

in debt causes households and firms to expect

future higher taxes is a key distinction between

Keynesian and classical views on the effective-

ness of discretionary fiscal policy).

4

Finally, as

with reduced-form regressions, VARs might not

reliably be able to resolve the timing issue.

By contrast, “narrative” approaches estimate

policy-driven changes in fiscal stimulus by look-

ing directly at the historical record of legisla-

tion and public statements. The advantage of

this approach is that careful attention can be

directed to picking the timing of the shocks by

examining carefully when policy decisions were

made and announced. But such studies are very

resource intensive, making their application

across countries almost impossible. Further,

they are subjective, just as VARs and reduced-

form analysis rely on identifying assumptions. In

practice, analysis has centered around a small

number of extraordinary episodes of military

buildups, and there are questions as to how

much can be learned from such episodes about

discretionary fiscal policy during downturns.

A final approach examines specific “natural

experiments,” such as the effects of tax rebates.

4

See Chung and Leeper (2007). Favero and Giavazzi

(2007) do include debt stock.

The advantage of this approach is that it can

be directed at specific episodes for which it is

relatively easy to identify the policy change and

its intent. The corresponding disadvantage is

that, by examining a specific case, it can be hard

to draw broader lessons for policy.

This empirical work provides a mixed

picture of the ability of government spend-

ing to stimulate private demand.

5

(There is

less evidence about revenue-based measures.)

Moreover, there appears to be a pattern

between the method used and the qualitative

results obtained. The table summarizes the

results of a selection of prominent papers in

the literature in terms of the signs of responses

of key variables to discretionary increases in

government spending.

In particular, SVAR-based studies in which

fiscal interventions are identified by assum-

ing that government spending is predeter-

mined within the quarter (see Blanchard and

Perotti, 2002) tend to find relatively strong

positive effects, whereas narrative stud

-

ies that rely on the reactions to episodes of

extraordinary spending have tended to find

much weaker, and even negative, relation-

ships between episodes of fiscal stimulus and

5

Results from case studies usually find positive

effects, but the effects are generally not as strong as

those generated by VAR studies. Studies of the 1975

tax rebates generally conclude that the effects were

positive but modest (that is, short-run multipliers of

about 0.2–0.5); see Modigliani and Steindel (1977)

and Blinder (1981). Studies of the 2001 tax rebates

have generated similar results; see Shapiro and

Slemrod (2002).

Assessment of Impacts of Discretionary Fiscal Policy Stimulus by Empirical Method

Output Private Consumption

Private Investment

in Durables

Private

Capital Investment

VAR studies Neutral to positive Neutral to positive Negative to positive Negative to positive

Narrative studies Positive Negative Negative . . .

Case studies Positive Positive . . . . . .

Note: Studies placed in the vector autoregression (VAR) category include Fatás and Mihov (2001); Mountford and Uhlig (2002);

Blanchard and Perotti (2002); and Galí, López-Salido, and Vallés (2007). Studies placed in the narrative category include Ramey and

Shapiro (1998) and Edelberg, Eichenbaum, and Fisher (1999). Case studies include Johnson, Parker, and Souleles (2006).

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

166

pliers cover a wide range, from positive through

insignificant to negative.

3

One reason is that

taking account of all the appropriate condition-

ing factors can be very difficult. Another reason

is methodological. Put simply, separating out

changes in discretionary fiscal policy from auto-

matic stabilizers and evaluating their effects is

very difficult—in particular, fiscal policy simul-

taneously both responds to and causes changes

in economic activity. This “endogeneity prob-

lem” poses a major challenge for estimating the

effects of fiscal policy, as discussed in Box 5.2.

How Has Discretionary Fiscal Policy

Typically Responded?

The previous section identified two types of

critique of fiscal policy: skepticism that discre-

tionary fiscal policy can be delivered efficiently,

owing to political constraints, and doubts that

it can be effective, for economic reasons. These

critiques frame the empirical analysis in this

3

A typical range of expenditure multipliers would be

from 0.5 (for example, Mountford and Uhlig, 2002) to

about 1 (for example, Blanchard and Perotti, 2002). But

Perotti (2007) has outliers as high as 4 and Krogstrup

(2002) as low as –2.

section, which examines how fiscal policy has

typically responded to downturns.

Defining economic downturns and measur-

ing fiscal stimulus are inevitably somewhat

subjective exercises. In the analysis that follows,

downturns are defined as periods during which

either the growth rate is negative or the output

gap is unusually negative, the precise thresh-

old depending on whether quarterly or annual

data are used. This definition is arguably more

sensible than defining a downturn simply in

terms of negative growth, because that would

miss periods during which output is significantly

below potential but still rising.

The measures of fiscal stimulus used in this

chapter all start with the primary fiscal balance,

the difference between total general govern-

ment revenues and expenditure net of interest

payments on consolidated general government

liabilities. Changes in the primary balance can

arise passively, as revenues and expenditures rise

and fall with economic activity, or actively, as

governments make choices about tax, transfer,

and spending policies. What is needed, there-

fore, is a measure of the cyclically adjusted pri-

mary balance, the intuition being that changes

in the cyclically adjusted primary balance should

reflect changes in policy. The first part of this

consumption.

6

Ramey (2008) suggests that this

difference relates to the way that VARs treat

timing—if discretionary fiscal policy measures

are pre-announced, and households decrease

their spending right away (as predicted by neo-

classical theory), VARs that measure the effect

based on actual changes to fiscal balances or

components might record a rise in the growth

rate of consumption on that date. This would

support a Keynesian view of fiscal policy, but

in fact the growth in consumption is driven

6

Note, however, that narrative studies of the effects

of tax changes find very large multipliers—see Romer

and Romer (2007).

by recovery from the previous fall. Narra-

tive approaches, on the other hand, take into

account the moment discretionary measures

are announced.

7

Compared with these studies,

the reduced-form approach employed in this

chapter is conceptually closest to the SVAR

approach of Blanchard and Perotti (2002); to

the extent that the timing criticism applies to

this paper and those like it, it also applies to

our methodology. However, a comparative nar-

rative study of all 41 economies in this study is

beyond the scope of this chapter.

7

But see also the rebuttal in Perotti (2007).

Box 5.2 (concluded)

167

section looks at the responses of fiscal policy

to changes in economic activity, identifying

automatic stabilizers with changes in the cycli-

cal component of the primary balance and

discretionary fiscal policy with changes in the

cyclically adjusted primary balance.

4

Construct-

ing this measure requires two slightly different

approaches, depending on the information

available for the economies being analyzed.

Evidence on the Responsiveness of Fiscal Policy

The empirical investigation begins with

analysis of advanced economies, for which long

spans of fiscal data are available on a quarterly

basis.

5

Discretionary fiscal actions are those that

change the cyclically adjusted budget balance,

using estimates of the output gap together with

estimates of income elasticities of revenues and

expenditures to extract the cyclical component

from the budget.

6

Figure 5.1 presents a sum-

mary of policy responses in G7 economies over

the past four decades. The numbers indicate

that discretionary fiscal stimulus has been deliv-

ered in downturns, but it has been used much

less frequently than automatic stabilizers and

monetary policy. Discretionary fiscal stimulus

has been used in about 23 percent of all down

-

turn quarters—less than half as frequently as

interest-rate easing—whereas automatic stabi-

lizers are observed in well over 95 percent of

downturns (upper panel).

7

Discretionary policy

4

As defined in Box 5.1 and the event analysis, the

cyclically adjusted balance is a residual and embodies all

changes in the primary balance not removed by cyclical

adjustment. This includes many factors not necessar-

ily related to output stabilization, such as the impact of

structural reform, one-off items, and other economic

events (including asset price changes that are not cyclical

in nature and could therefore be identified as “auto-

matic” changes in the fiscal balance—see Jaeger and

Schuknecht, 2007).

5

For further details about the following analysis, see

Leigh and Stehn (forthcoming).

6

These elasticities are taken from the OECD Economic

Outlook; see Appendix 5.1 for details.

7

Note that automatic stabilizers do not necessarily

ease in all downturns, because the applied definition of

a downturn does not rule out an increase in growth or

the output gap (as long as the output gap is unusually

negative).

how has discretionary Fiscal Policy tyPically resPonded?

Discretionary fiscal policy has been used less frequently than monetary policy and

automatic stabilizers during downturns, and has taken longer to arrive.

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 20 40 60 80 100

Source: IMF staff calculations.

G7 comprises Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, and United

States.

Share of downturns with easing in:

Lag after start of downturn until policies eased

Figure 5.1. How Often and Quickly Has Fiscal Stimulus

Been Used in G7 Economies?

Group of 7 (G7) Anglophone G7 countries Other G7

Cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Cyclically adjusted

current spending

Cyclically adjusted

revenue

Cyclical primary

balance

Nominal policy

interest rate

Capital spending

Cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Cyclically adjusted

current spending

Cyclically adjusted

revenue

Cyclical primary

balance

Nominal policy

interest rate

Capital spending

Quarters

Percent

1

1

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

168

also arrives later, on average about two and a

half quarters after the onset of a downturn, and

about one and a half quarters after interest-rate

easing (lower panel). Capital spending is par-

ticularly slow, with an arrival lag of almost four

quarters. By contrast, automatic fiscal easing,

proxied by a fall in the cyclical primary balance,

occurred in almost all downturns in the quarter

of the downturn itself.

The size of discretionary fiscal easing is also

much smaller on average than that of automatic

stabilizers. Figure 5.2 shows average impulse

responses of discretionary fiscal measures,

automatic stabilizers, and interest rates for the

G7 economies, drawing from vector autoregres-

sions (VARs) estimated for two samples, an

“early” sample covering 1980:Q1–1991:Q4 and

a “late” sample covering 1992:Q1–2007:Q4.

8

In

both samples, the discretionary fiscal easing is

much smaller than the automatic stabilizers and

is slower to arrive than both changes in interest

rates and automatic stabilizers. However, a com-

parison of the two panels also suggests that the

countercyclical response of discretionary fiscal

policy has strengthened since the early 1990s.

9

The responses of spending and revenue compo-

nents in the early sample reflect a combination

of mildly procyclical revenue increases, small

countercyclical current spending increases, and

large procyclical capital spending cuts. The

greater degree of fiscal policy countercyclical-

ity observed since the early 1990s is the result

of cuts in revenues, larger increases in current

spending, and smaller procyclical cuts in capital

spending. The response of automatic stabiliz-

8

See Appendix 5.1 for more details. Note that, unlike

much of the VAR literature, the analysis presented here

does not evaluate the response of growth to fiscal policy

shocks. Rather, the focus is on the response of fiscal

policy variables to changes in growth.

9

In the early sample, discretionary fiscal policy is pro-

cyclical on impact and provides a cumulative procyclical

contraction of around 0.1 percentage point of potential

GDP over four quarters. In the later sample, even though

discretionary policy still produces no stimulus on impact,

it leads to a cumulative stimulus of 0.2 percentage point

over four quarters. This finding is consistent with, for

example, Galí and Perotti (2003) and World Economic

Outlook (September 2003).

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Early Sample (1980:Q1–91:Q4)

Late Sample (1992:Q1–2007:Q4)

Following an unexpected 1 percentage point fall in growth below potential, interest

rates and the automatic component of the fiscal balance ease on impact;

discretionary fiscal stimulus takes longer to arrive. In recent years, discretionary

fiscal policy has become more countercyclical.

Figure 5.2. How Strong Was the Fiscal Policy Response

in G7 Economies?

(Percentage point deviation; quarters on x-axis; shock occurs in period

zero)

Interest rate Discretionary policy Automatic stabilizers

169

ers remained unchanged in the second sample,

while that of monetary policy strengthened.

Figure 5.3

shows that there are noticeable

cross-country differences across advanced econo

-

mies. Discretionary fiscal policy and monetary

policy have been more timely and more coun-

tercyclical in the United States, Canada, and the

United Kingdom (the G7’s three Anglophone

countries) than in the rest of the G7. The

other Organization for Economic Cooperation

and Development (OECD) member countries

display even weaker countercyclicality than the

United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom

in both monetary and discretionary fiscal policy.

Data Uncertainties and the Risk of Debt Bias

A concern that often arises regarding coun-

tercyclical fiscal activism is that policymakers

may respond in an asymmetric manner, easing

in downturns and not tightening sufficiently in

upturns, implying a permanent increase in the

public-debt-to-GDP ratio with potentially adverse

consequences for long-run growth. To investi-

gate whether fiscal policy in G7 countries has

displayed such an asymmetric tendency, the VAR

framework is adapted to allow for an asymmetric

response to upturns and downturns (see Appen-

dix 5.1). The results suggest that both fiscal

policy and monetary policy are subject to an eas-

ing bias; that is, more easing during downturns

than tightening during upturns (Figure 5.4). In

contrast, automatic stabilizers respond in a sym-

metric way, with the easing observed in down-

turns almost exactly offset by tightening during

upturns.

Hence, although discretionary fiscal policy

has been actively used, there are valid concerns

about debt bias. For illustration, a case study

of tax-based stimulus legislation in the United

States is provided in Box 5.3. The study finds

that, although reasonably timely, 38 percent of

cyclically motivated tax cuts were permanent.

An additional concern in the analysis of

countercyclical fiscal activism is that policymak-

ers face substantial uncertainties regarding the

cyclical position and run the risk of destabilizing

are Fiscal Policy reactions diFFerent in emerging and advanced economies?

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Change in interest rate

Change in discretionary fiscal balance

Following an unexpected 1 percentage point fall in growth below potential,

Anglophone countries have provided both monetary and fiscal stimulus; the rest of

the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries have

provided a weaker monetary response and procyclical discretionary fiscal tightening.

The figure displays policy responses for the late sample (1992:Q1–2007:Q4).

Figure 5.3. How Have Fiscal Policy Responses Varied

across Advanced Economies?

(Percentage point deviation; quarters on x-axis; shock occurs in period

zero)

Group of 7 (G7)

Other G7

Anglophone G7 countries

Other OECD

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

170

the economy by responding to erroneously per-

ceived downturns. This appears to be a serious

problem, based on an assessment of the reliabil-

ity of preliminary GDP estimates produced by

national authorities.

10

There is a strong negative

relationship between preliminary growth esti-

mates and subsequent revisions. Forty percent

of preliminary estimates indicating negative

quarter-over-quarter growth were subsequently

revised to positive growth.

11

Forecast efficiency

tests find strong evidence of a bias toward pes-

simism in preliminary growth estimates.

12

To investigate how fiscal policy in G7 coun-

tries has been affected by errors in growth

estimates, the VAR framework is augmented

with growth-estimation errors (see Appendix

5.1). The results reported in Figure 5.5 confirm

that both fiscal and interest rate policy have

been affected by errors in preliminary growth

estimates, with a 1 percentage point fall in

perceived growth relative to final revised growth

associated with an easing in interest rates and

the discretionary fiscal-balance-to-potential GDP

ratio by about 0.2 percentage point. This finding

suggests that concern over policy errors is well

founded, especially as fiscal policy decisions

appear to be less easily reversed than monetary

policy decisions, and fiscal policy errors bear

potentially long-lived consequences for debt.

Are Fiscal Policy Reactions Different in

Emerging and Advanced Economies?

Some of the reservations about the applica-

tion of discretionary fiscal policy may apply

even more strongly in less advanced economies.

Unfortunately, although the data in the previous

section were available at quarterly frequency,

consistent data for a broader set of econo-

10

See Appendix 5.1. See also Cimadomo (2008) for

further analysis of fiscal policy using real-time data.

11

At the same time, 30 percent of quarters that, accord-

ing to the final data actually had negative growth, showed

positive growth in preliminary estimates.

12

While remaining statistically significant, this bias

appears to have declined in recent years, possibly reflect-

ing the more stable and predictable growth environment.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-1.0

-0.8

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Change in interest rate

Change in fiscal balances

Following a 1 percentage point shock to growth, both discretionary fiscal policy and

monetary policy are subject to an easing bias, with more stimulus during downturns

than tightening during upturns. In contrast, automatic stabilizers respond

symmetrically to upturns and downturns. The figure displays policy responses for

the late sample (1992:Q1–2007:Q4).

Figure 5.4. Is There a Bias toward Easing during

Downturns in G7 Economies?

(Percentage point deviation; quarters on x-axis; shock occurs in period

zero)

Upturn Downturn

Automatic stabilizers

Discretionary policy

Automatic

stabilizers

Discretionary policy

171

mies are available only at annual frequency.

In what follows, the analysis uses a sample of

21 advanced economies and 20 emerging econo

-

mies, covering the period from 1970 to 2007.

13

The definition of “downturn” is conceptually

the same as used previously with the quarterly

data, but “unusually negative” is now defined

as below –0.5 standard deviation of the output

gap, on account of the use of annual data.

14

For advanced economies, OECD estimates of

income elasticities of revenues and expendi-

tures are used to calculate the cyclical balance.

However, such estimates are not available for

emerging economies, and so it is assumed

that revenues move one-for-one with the busi-

ness cycle, but expenditures do not—that is,

the income elasticity of revenues is 1 and the

income elasticity of expenditures is zero (see

Appendix 5.1 for details). A fiscal expansion is

then defined as a negative change in the cycli-

cally adjusted primary balance of more than

0.25 percentage point and a fiscal contraction

as a positive change of more than 0.25 percent

-

age point. When the change in the cyclically

adjusted primary balance is less than 0.25 per

-

centage point (either positive or negative), fiscal

policy is considered neutral. Hence, we have

three states for the fiscal stance: stimulus (397

episodes), neutral (155 episodes), and tighten-

ing (437 episodes).

In addition to the assumptions necessarily

imposed when choosing data sets and defini-

tions, a number of caveats apply to analysis using

these measures. In particular, the use of annual

data limits the ability to accurately characterize

fiscal interventions that begin and end within

a year. Second, what is relevant is policymak-

ers’ perceptions of the state of the economy in

real time, which might differ substantially from

inferences made using revised data, but, in the

13

See Appendix 5.1 for a list of economies and episodes

of downturns.

14

Correspondingly, upturns are defined as episodes

during which the output gap is above 0.5 standard devia-

tion. Potential output is measured using the Hodrick-

Prescott filter, with λ set to 6.25, the value recommended

in Ravn and Uhlig (2002).

the macroeconomic eFFects oF discretionary Fiscal Policy

Following an erroneously perceived 1 percentage point fall in growth, both

discretionary fiscal policy and monetary policy have eased, particularly in

Anglophone countries. The figure displays policy responses for the late sample

(1992:Q1–2007:Q4).

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.25

-0.20

-0.15

-0.10

-0.05

0.00

0.05

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Change in interest rate

Change in fiscal balances

Figure 5.5. Did G7 Economies Respond to Erroneously

Perceived Downturns?

(Percentage point deviation; quarters on x-axis; shock occurs in period

zero)

Group of 7 (G7) Other G7Anglophone G7 countries

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

172

This box takes a closer look at whether fiscal

interventions in the United States have been

timely, temporary, and targeted (TTT). A

recent data set compiled by Romer and Romer

(2007) of all significant tax changes signed

into law since 1945 permits a detailed analysis

of this issue. By consulting official documents,

Romer and Romer distinguish tax changes

that were explicitly motivated by cyclical

considerations from those motivated by other

factors, including long-run growth support,

debt reduction, and the financing of additional

expenditures. Of all the 50 significant federal

tax actions identified, 7 were assessed as cycli-

cal, and, of these, 5 were tax cuts designed to

stimulate short-run growth.

This box focuses on these five tax cuts,

implemented between 1970 and 2002, as well

as the Economic Stimulus Act, signed into law

in February 2008. The box assesses how quickly

after the onset of a downturn the tax cuts were

legislated and implemented, how temporary

they were, and how well targeted they were. In

assessing how close to a downturn the tax cuts

arrived, the analysis defines a downturn as in

the main text. Growth data to assess the 2008:

Q2 stimulus are not yet available.

The main results are as follows:

•

Timeliness: Four out of the five cyclically moti-

vated tax cuts occurred within one quarter of

a downturn (see table). In the case of 2002,

the stimulus arrived three quarters after the

downturn. The average implementation lag of

tax cuts; that is, the delay between the signing

of the legislation into law and its impact on

revenue, was one quarter.

•

Temporariness: Although only one of the six

cyclically motivated tax cuts was permanent,

the remainder contained a permanent

component (see table). In particular, about

79 percent of the tax cuts were designed to be

temporary, with an average planned dura-

tion of two quarters. Some of the tax cuts

were subsequently extended, so that a smaller

proportion—62 percent—actually ended up

Box 5.3. Have U.S. Tax Cuts Been “TTT”?

The main authors of this box are Daniel Leigh and

Sven Jari Stehn.

How Timely, Temporary, and Targeted Were the Tax Cuts?

Legislated Tax Cut

Timeliness

Temporariness

1

Targeting

Date

stimulus

arrived

Name of

act

Size of

stimulus

(percent

of GDP)

Date of

nearest

downturn

2

Inside

lag

(quarters)

3

Proportion temporary

Duration of temporary

portion (quarters)

Bang-

for-the-

buck score

4

Planned Actual Planned Actual

1970:Q1 Tax Reform 1.2 1970:Q1 1 0 0 permanent 1.0

1975:Q2 Tax Reduction 3.6 1975:Q1 1 97 78 2.3 1.0 2.5

1977:Q3 Tax Reduction

and Simplification

1.0 1977:Q4 1 77 67 1.3 1.0 1.9

2001:Q3 Economic Growth

and Tax Relief

Reconciliation

1.7 2001:Q3 1 100 100 1.3 1.3 2.4

2002:Q2 Job Creation

and Worker

Assistance

1.7 2001:Q3 1 100 67 3.7 4.0 1.3

2008:Q2 Economic Stimulus 1.1 . . . 1 100 . . . 1.6 . . . 2.7

Mean 1.6 . . . 1 79 62 2.0 1.8 2.0

1

Temporary stimulus is defined as a stimulus that expires. Actual duration may exceed planned duration because of legislated

extensions.

2

Downturn is defined as a quarter with negative or below-trend growth and an output gap more than one standard deviation below

zero.

3

Inside lag denotes the period between the date the stimulus was signed into law and the date it was implemented (quarter in which

tax liabilities actually changed).

4

Bang-for-the-buck score (3 = high, 2 = medium, 1 = low) indicates the degree of cost-effectiveness according to CBO (2008)

classification.

173

absence of consistent real-time vintages of data,

it is difficult to adjust for this difference.

Bearing these caveats in mind, the analysis

identified the following stylized facts:

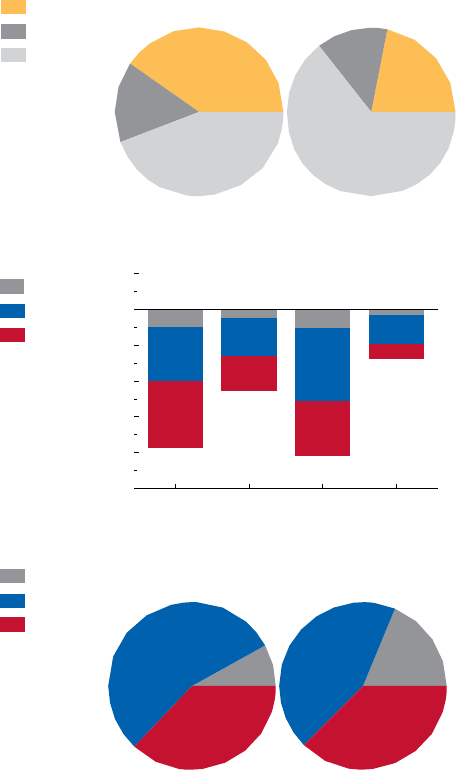

• Emerging economies respond during down

-

turns with fiscal stimulus only half as fre-

quently as advanced economies: 22 percent

versus 41 percent (Figure 5.6, top panel).

When emerging economies do implement fis-

cal stimulus, the response is slightly higher, as

measured by changes in the cyclically adjusted

primary balance as a percent of potential

GDP (Figure 5.6, middle panel, first and third

bars). But this is because downturns are larger

(Figure 5.6, middle panel, second and fourth

bars).

• In just over one-third of episodes, fiscal stimu

-

lus involved a mixture of revenue and expen-

diture changes. Of those that relied mainly on

one kind of stimulus, expenditure measures

dominate for both advanced and emerging

economies (Figure 5.6, bottom panel).

• In emerging economies, changes in the over

-

all primary balance are usually procyclical,

despite countercyclical effects from automatic

stabilizers (Figure 5.7, top panel).

15

And they

are more procyclical in downturns when

15

This finding is consistent with Kaminsky, Reinhart,

and Végh (2004) and a number of other studies. It holds

advanced economies are simultaneously expe-

riencing downturns, consistent with rises in

external financing premiums (Figure 5.7, bot

-

tom panel). In advanced economies, changes

in the primary fiscal balance are, on average,

countercyclical, mostly because of automatic

stabilizers, as measured by changes in the

cyclical balance.

The Macroeconomic Effects of

Discretionary Fiscal Policy

Having defined downturns and episodes of

fiscal stimulus, this section turns to the central

question: What are the macroeconomic effects

of discretionary fiscal policy, especially during

downturns? An event analysis identifies some

of the basic patterns, using the same elasticity-

based fiscal impulse measure as in the previous

section, and then regressions provide a more

systematic assessment of cause and effect.

An Event Analysis of Episodes of Downturns and

Fiscal Stimulus

The event analysis shows the dynamics of key

macroeconomic variables—real GDP growth, the

across both fixed and floating exchange rate regimes at

the time of the episode.

the macroeconomic eFFects oF discretionary Fiscal Policy

being temporary, and 38 percent became

permanent.

•

Targeting: The targeting efficiency of each

tax cut package is assessed using the cost-

effectiveness classification scheme of the

Congressional Budget Office (CBO, 2008),

which indicates the likely bang-for-the-buck

impact on aggregate demand of a range of

possible fiscal stimulus tools. Based on this

classification scheme, three out of the six

cyclically motivated tax cuts are classified as

cost-effective. More than half of the content

of these three tax packages consisted of per-

sonal direct transfers and personal lump-sum

rebates—two fiscal tools assessed as being

the most cost-effective by the CBO. The most

recent, 2008, stimulus scored highest on this

account, followed by 1975 and 2001. The

least cost-effective stimulus measures were

the 1970 and 2002 tax reductions, the bulk

of which consisted of corporate lump-sum

rebates and personal and corporate tax-rate

reductions.

Hence, for the most part, fiscal interventions

in the United States have been timely, but not

always temporary or well targeted.

Box 5.3 (concluded)

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

174

debt-to-GDP ratio, inflation, exchange rates, the

current account, and money growth—around

episodes of downturns. Table 5.1 and Figure 5.8

show how macroeconomic variables move

together with fiscal stimulus before, during, and

after downturns. As expected, the debt-to-GDP

ratio increases following a fiscal stimulus and

improves when it tightens, while current account

balances improve in the downturn year when

there is tightening and deteriorate when there is

stimulus. But for other variables, the results are

generally ambiguous. In particular, growth rates

are larger in episodes without fiscal stimulus, but

the change in growth rates from the downturn

year to the first year after the downturn is some-

what larger when there is fiscal stimulus. These

observations are common across advanced and

emerging economies.

Table 5.2

shows median values of real GDP

growth across all economies during episodes

of downturns and fiscal stimulus for a num-

ber of variables that theory suggests could

have important effects: public debt, current

account balances, trade openness, and the

exchange rate regime.

16

Figure 5.9 shows the

difference between growth rates in the year of

the downturn and the year following. Looking

across these conditioning factors, there is little

discernible difference in the impact of fiscal

policy from variations in the current account

balance, openness to trade, and the exchange

rate regime, despite what theory suggests. How-

ever, the level of public debt does appear to be

associated with consistent differences in growth

outcomes—economies that implement fiscal

stimulus and have high public debt going into

a downturn typically experience lower growth

rates before and after the downturn year and

16

For the first three of these variables, the results are

divided into “high” and “low” cases, based on the average

for that variable three years before the recession episode.

The thresholds for high and low are the median values of

the overall sample, except debt, for which the threshold

for high debt is 75 percent for advanced economies

and 25 percent for emerging economies. Exchange

rate regimes are categorized according to whether the

exchange rate was fixed or floating in the first year of the

downturn.

Advanced

economies

Emerging

economies

Both

Expenditure

Revenue

Total number of responding economies that pursued stimulus driven by:

-2.5

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

Figure 5.6. Composition of Fiscal Stimulus during

Downturns for Advanced and Emerging Economies

The pie charts at the top show the types of fiscal policy response—stimulus,

neutral, or tightening—during episodes of downturns for advanced economies and

emerging economies. The bar chart indicates the average size of fiscal stimulus.

Areas indicate the average proportion of the total sample stimulus from changes in

revenues only, changes in expenditures, or both. The pie charts at the bottom

indicate the frequency of using revenue only, changes in expenditures, or both for

advanced economies and emerging economies.

Average change in cyclically adjusted primary balance during downturns

Emerging

economies

Advanced

economies

Total number of fiscal responses during downturns

6

34

23

5

3

7

Tightening

Neutral

Stimulus

47

24

68

64

16

10

Both

Expenditure

Revenue

1,2

Emerging

economies

Advanced

economies

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Average change in cyclically adjusted primary balance associated with various types of

fiscal stimulus weighted by the share of fiscal stimulus cases of a particular type among

countries that responded with fiscal stimulus during downturns.

For each group of economies the left-hand column is the change in cyclically adjusted

primary balance in percent of GDP. The right-hand column is the change in cyclically

adjusted primary balance in percent of GDP scaled by the standard deviations of changes

in output gap.

1

2

Unadjusted Scaled

Unadjusted Scaled

175

less of a pickup in growth in the year following

fiscal stimulus, whereas high-debt economies

that implement fiscal tightening experience

stronger gains in growth.

Turning to the ways fiscal policy was imple-

mented, economies that employed a combi-

nation of revenue and expenditure stimulus

experienced less-severe downturns compared

with those that relied on revenue or expenditure

measures alone, although revenue-based policies

were associated with faster recoveries and higher

growth in the years following (Table 5.3).

17

Con-

versely, expenditure-based fiscal tightening was

associated with higher growth in years following

the downturn.

In summary, the event analysis indicates that

taking into account debt and the composition

of fiscal stimulus could be important to under-

standing the effects of fiscal policy. Conversely,

it is difficult to see clear patterns with other vari-

ables that theory indicates could be important.

Regression Analysis

Event analysis records only associations

between fiscal stance and the dynamics of

the macroeconomic variable in question, but

indicates nothing about causation between the

variables.

18

Further, by characterizing variables

according to simple categories and considering

them one by one in isolation from one another

might hide important information about the

size of and interaction between variables. A

regression framework is used to address this.

The conceptual framework for these

regressions is an examination of the effects

of discretionary fiscal policy on real GDP growth,

while controlling for the potential effects from

monetary policy and other sources of demand

17

The small sample size of episodes involving revenue

impulse, however, warrants caution in interpreting these

results.

18

Growth associations are a prime example: If there are

lower growth rates in downturns when fiscal policy was

very aggressive, is the appropriate conclusion that fiscal

policy is not effective or that fiscal policy had to be very

aggressive because the downturn was very severe?

the macroeconomic eFFects oF discretionary Fiscal Policy

ADV EME ADV EME ADV EME

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Average change in the balance scaled by the standard deviations of changes in output

gap. A good year is defined as a year in which the GDP-weighted average gap of advanced

economies is below the median GDP-weighted average gap of advanced economies across

all years.

Responses of advanced and emerging economies, depending on position in cycle

The upper bar chart shows average fiscal policy responses for advanced (ADV) and

emerging (EME) economies in (left to right) GDP downturn episodes, neutral

episodes, and upturn episodes. A negative number indicates fiscal stimulus.

Discretionary fiscal policy is associated with the cyclically adjusted primary balance.

The lower bar chart shows average fiscal policy responses in emerging economies

when advanced economies are in upturns and downturns. In both charts, the

average change in the balance is scaled by the standard deviations of changes in the

output gap.

Figure 5.7. Fiscal Policy Responses in Downturns and

Upturns

(Average change, percent of GDP)

Change in primary balance

Change in cyclically adjusted primary balance

Change in cyclical balance

Downturn Neutral Upturn

1

Good year Bad year

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Response of emerging economies to downturn, depending on position of

advanced economies in cycle

1

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

176

stimulus, and taking into account factors that

might affect the transmission of fiscal stimulus.

The main regressor of interest is the fiscal

impulse measure.

19

Ideally, the fiscal impulse

measure would pick up all discretionary changes

in fiscal stance, whether from systematic reac-

tions to the state of the economy or nonsystem-

atic (that is, unexpected) discretionary actions.

The systematic component of the fiscal impulse

measure is, however, endogenous, which leads

to problems with statistical inference. Moreover,

as discussed in Box 5.2, it is very difficult to

distinguish systematic changes in fiscal policy

from automatic stabilizers. In principle, the

elasticity-based fiscal impulse measure used in

the previous section should achieve this, but

19

Note that all the variables are now continuous and no

longer use the categories of the event analysis.

unless the elasticities are perfectly accurate for

each period—and potential output is measured

correctly—this type of fiscal impulse measure

will likely suffer from additional, measurement-

error-related endogeneity, undermining the

validity of the regressions.

To reduce these endogeneity problems and

check for robustness, a second fiscal impulse

measure is used that focuses exclusively on

the nonsystematic component of discretion-

ary fiscal policy (as is also the case in the fiscal

literature that uses structural vector autoregres-

sion (SVAR) and “narrative” approaches; see

Box 5.2). This measure aims to identify unex

-

pected changes in fiscal stance, based for each

country on separate regressions of revenues

and expenditures on output growth and a time

trend—see Appendix 5.1 for details. (In what

follows, this measure will be referred to as the

Table 5.1. Macroeconomic Indicators around Downturns, with and without a Fiscal Impulse: All

Economies

1

Median

Number of

Observations

in Downturn

Three-Year

Average before

Downturn

One Year

before

Downturn

Year of

Downturn

One Year

after

Downturn

Four-Year

Average after

Downturn

Real GDP growth

Fiscal stimulus 51 3.1 2.2 –0.1 3.6 3.2

Fiscal tightening 83 2.5 2.8 0.7 4.2 3.6

Change in debt-to-GDP ratio

Fiscal stimulus 43 –1.4 –0.5 2.2 1.1 0.8

Fiscal tightening 61 1.4 1.5 1.2 –0.9 –1.2

Change in cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Fiscal stimulus 51 0.0 –0.2 –1.1 0.0 0.2

Fiscal tightening 83 0.0 0.1 1.6 –0.2 0.2

Inflation

Fiscal stimulus 48 5.6 5.5 4.7 3.0 2.7

Fiscal tightening 78 7.1 6.2 5.2 5.0 5.1

Change in nominal exchange rate

2

Fiscal stimulus 41 –0.6 0.0 2.9 –0.5 0.1

Fiscal tightening 72 4.6 3.3 7.9 3.5 2.3

Current account surplus

Fiscal stimulus 51 –2.4 –2.9 –0.8 –0.9 –1.2

Fiscal tightening 81 –0.9 –0.8 0.0 0.2 –0.1

Real money growth

Fiscal stimulus 32 5.0 2.6 1.7 4.2 4.8

Fiscal tightening 54 4.6 4.3 3.3 4.9 5.0

Note: For each variable, the median is recorded for the three categories of fiscal stance during the first year of the downturn: stimulus, neutral

policy, and tightening. In each case, values are recorded for the average of the median three years before the downturn, one year before the

downturn, the first year of the downturn itself, one year after the whole downturn episode, and the average for the four years after the downturn

episode. Note that some downturns last for more than one year. In a multiyear downturn, the year after the downturn is the first year after the

last downturn year.

1

Fiscal impulse identified during the first year of a downturn as a decline in the cyclically adjusted primary balance to GDP below 0.25 percentage

point of GDP.

2

Exchange rate is given as local currency/U.S. dollars (+ sign denotes a depreciation).

177

the macroeconomic eFFects oF discretionary Fiscal Policy

regression-based fiscal impulse measure, to dis-

tinguish it from the elasticity-based measure.)

Other regressors include two lags of real GDP

growth, to control for endogenous inertia in the

economy; real money growth (contemporaneous

and two lags), as a measure of monetary policy;

changes in foreign demand (contemporaneous

and two lags); and government size. These were

found to be significant at the 10 percent level

and were retained in all regression specifications

that follow.

Table 5.4

presents the key results in terms

of responses of real GDP to a 1 percent fiscal

impulse, using both the elasticity-based and

regression-based fiscal impulse measures.

20

The

values show the output effects in the year of the

fiscal intervention and three years later, with a

positive number indicating that positive fiscal

stimulus raises output.

21

The results for the base-

line specification are presented in the first row.

For both fiscal impulse measures, the estimated

effect of fiscal stimulus on output growth in the

baseline specification is weak—closer to zero

than the Keynesian assumption of 1 or more—

and turns negative after three years. However, as

can be seen in the second and third rows of the

table, this conceals important differences across

countries. In advanced economies, the multipli-

ers are statistically significant and moderately

positive—a 1 percentage point fiscal stimulus

leads to an increase in real GDP growth of about

0.1 percent on impact, and up to 0.5 percent

above its level in year 0 after three years. This is

broadly comparable with the effects found from

previous SVAR studies and case studies. By con-

trast, although emerging economies see impact

effects similar to those of advanced economies,

the effects on output in the medium term are

consistently negative across both fiscal impulse

measures—for these economies, discretionary

20

See Appendix 5.1 for tables of coefficient estimates

and regression diagnostics.

21

Note, however, that the regressions underlying the

first nine rows do not distinguish between fiscal stimulus

and fiscal tightening—a negative effect on output from

fiscal tightening is therefore assumed to be consistent

with a positive effect from fiscal stimulus.

Figure 5.8. Macroeconomic Indicators after Downturns,

with and without a Fiscal Stimulus

The bar charts indicate changes in macroeconomic indicators from the year of

downturn to the first year after downturn.

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Fiscal stimulus during the first year of a downturn is defined as a decline in the cyclically

adjusted primary balance to GDP below 0.25 percentage point of GDP.

Exchange rate is given as local currency/U.S. dollar (+ sign denotes a depreciation).

Value for emerging economies with fiscal stimulus is –10.5; with fiscal tightening, –21.2.

Fiscal tightening

1

-8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6

Emerging economies

Advanced economies

All

Fiscal stimulus

Neutral fiscal policy

64

2

0-2

-4

-6-11

Change in current

account balance

Change in nominal

exchange rate

Change in inflation

Change in real GDP

growth

Debt-to-GDP ratio

Cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Real money growth

2

2

1

64

2

0-2

-4

-6-22

Change in current

account balance

Change in nominal

exchange rate

Change in inflation

Change in real GDP

growth

Debt-to-GDP ratio

Cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Real money growth

2

Change in current

account balance

Change in nominal

exchange rate

Change in inflation

Change in real GDP

growth

Debt-to-GDP ratio

Cyclically adjusted

primary balance

Real money growth

2

CHAPTER 5 Fiscal Policy as a countercyclical tool

178

fiscal policy does indeed appear to do more

harm than good.

The output responses shown in the next six

rows of the table indicate that, overall, rev

-

enue-based stimulus measures seem to be more