Audit Report

The Social Security

Administration’s Expansion of

Health Information Technology to

Obtain and Analyze Medical

Records for Disability Claims

A-01-18-50342 | January 2022

MEMORANDUM

Date: January 3, 2022

Refer To: A-01-18-50342

To:

Kilolo Kijakazi

Acting Commissioner

From:

Gail S. Ennis,

Inspector General

Subject:

The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of Health Information Technology to Obtain and

Analyze Medical Records for Disability Claims

The attached final report presents the results of the Office of Audit’s review. The objective was

to assess the Social Security Administration’s efforts to expand the use of health information

technology to obtain and analyze medical records for disability claims.

If you wish to discuss the final report, please contact Michelle L. Anderson,

Assistant Inspector General for Audit.

cc: Trae Sommer

Attachment

The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of

Health Information Technology to Obtain and Analyze

Medical Records for Disability Claims

A-01-18-50342

January 2022 Office of Audit Report Summary

Objective

To assess the Social Security

Administration’s (SSA) efforts to

expand the use of health information

technology (health IT) to obtain and

analyze medical records for disability

claims.

Background

To make disability determinations,

SSA (a) manually requests medical

records and receives them in paper

format (mail or fax) or through

Electronic Records Express (ERE),

which is SSA’s secure web portal, or

(b) requests and receives them

automatically from health IT.

Health IT is a broad concept that uses

an array of technologies, such as

electronic health records and

exchange networks, to record, store,

protect, retrieve, send, and receive

medical records securely over the

Internet.

It can take SSA days, week, or months

to obtain paper records. SSA does not

track the time from when it requests

and receives ERE records; whereas

health IT records arrive in seconds or

minutes.

SSA uses its Medical Evidence

Gathering and Analysis through Health

Information Technology (MEGAHIT)

software to automatically request and

receive health IT records and perform

data analysis.

Conclusion

Despite spending more than 10 years trying to increase the

number of medical records received through health IT, SSA still

receives most records in paper or ERE format. In the Fiscal

Year (FY) that ended on September 30, 2020, SSA received only

11 percent of medical records through health IT.

SSA experienced a decreasing trend in adding new health IT

partners from 56 in FY 2018 to 12 in FY 2021 (as of August).

During this time, SSA reduced the number of staff and contractors

involved in health IT outreach and did not fully fund projects to

increase electronic medical evidence. Also, expanding the number

of health IT records by adding new partners is not a unilateral

decision made by SSA, as prospective partners must be willing

and able to meet SSA’s technical requirements, and COVID-19

was a factor. In October 2021, SSA informed us it was (a) working

on Memorandums of Understanding with 3 entities to exchange

health IT records with over 30 large health IT organizations and

(b) adding more staff to develop and implement strategies to

expand health IT.

Challenges in expanding the number of health IT records include

some partners’ inability to send sensitive medical records,

acceptance of SSA’s authorization form to release records to the

Agency (Form SSA-827), and medical industry-wide differences in

patient-identifying data fields.

Additionally, SSA has had limited success analyzing medical

records because MEGAHIT is limited to analyzing only structured

data. MEGAHIT generated data extracts on only 7.3 percent of the

1.6 million health IT records SSA received in FY 2020. The

extracts assist SSA disability examiners in making accurate

disability determinations. Since 2018, SSA has been developing

and testing the Intelligent Medical-Language Analysis GENeration

application with new capabilities for reviewing medical records. As

of August 2021, SSA was still testing and rolling out this application

to its offices.

Recommendation

We recommend SSA intensify efforts to increase the number of

health IT partners. SSA agreed with the recommendation.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Objective ............................................................................................................................... 1

Background .......................................................................................................................... 1

The Social Security Administration’s Process for Obtaining Medical Records ............ 2

Benefits of Health Information Technology.................................................................. 4

Prior Report on Health Information Technology ......................................................... 5

Scope and Methodology ................................................................................................. 5

Results of Review ................................................................................................................ 5

The Agency’s Evolving Strategy for Obtaining and Analyzing Medical Records ......... 6

Challenges the Agency Faces in Obtaining and Analyzing Health Information

Technology Medical Records ......................................................................................... 8

Challenges with Obtaining Sensitive Records ........................................................ 11

Challenges with the Agency’s Authorization Form to Obtain Health Information

Technology Records ................................................................................................ 11

Challenges Matching Patient-identification Information ......................................12

Challenges in Analyzing Medical Evidence Electronically ..................................... 13

The Agency’s Plan for Increasing Electronic Medical Records for Fiscal Year 2021

and Beyond ...................................................................................................................14

Recommendation ...............................................................................................................14

Agency Comments .............................................................................................................. 15

– The Social Security Administration’s Medical Record Payment Rates .... A-1

– Prior Report Recommendation Status ...................................................... B-1

– Scope and Methodology ............................................................................ C-1

– Timeline of the Social Security Administration’s Use of Health

Information Technology .............................................................................. D-1

–Summary of Federal Health Information Technology Legislation ........... E-1

– Agency Comments ..................................................................................... F-1

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342)

ABBREVIATIONS

C.F.R. Code of Federal Regulations

DDS Disability Determination Services

ERE Electronic Records Express

Form SSA-827 Authorization to Disclose Information to the Social Security Administration

FY Fiscal Year

GAO Government Accountability Office

Health IT Health Information Technology

HHS-ONC The Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National

Coordinator for Health Information Technology

IMAGEN Intelligent Medical-language Analysis GENeration

MEGAHIT Medical Evidence Gathering and Analysis through Health Information

Technology

OIG Office of the Inspector General

POMS Program Operations Manual System

Pub. L. No. Public Law Number

SSA Social Security Administration

Stat. Statutes at Large

U.S.C. United States Code

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 1

OBJECTIVE

Our objective was to assess the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) efforts to expand the

use of health information technology (health IT)

1

to obtain and analyze medical records for

disability claims.

BACKGROUND

SSA provides Disability Insurance benefits

and Supplemental Security Income disability

payments to eligible individuals.

2

The SSA field office generally forwards the claim to the

disability determination services (DDS) in the State or other office with jurisdiction to determine

whether an applicant is disabled under SSA’s criteria.

3

Disability applicants must inform SSA

about or submit all evidence known to him/her that relates to whether he/she is blind or

disabled.

4

An applicant or his/her representative can submit records directly to SSA. An

applicant can also sign a Form SSA-827, Authorization to Disclose Information to the Social

Security Administration,

5

to allow SSA to obtain copies of medical records from health care

providers that have evaluated, examined, or treated him/her. SSA’s policy states, “Before we

make a determination that the claimant is not disabled, we will . . . [m]ake every reasonable

effort to develop the claimant’s complete medical history.”

6

There are approximately 624,000 physicians and 6,000 hospitals in the United States.

7

In the

Fiscal Year (FY) ended September 30, 2019, health care organizations provided approximately

80.7 percent of the records SSA used to make disability determinations (see Table 1).

1

SSA uses health IT to automatically request and receive disability applicants’ medical information electronically.

2

42 U.S.C. §§ 423 and 1381a.

3

42 U.S.C. §§ 421 and 1383b(a); 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.1601 and 416.1001.

4

20 C.F.R. § 404.1512(a)(1) and 416.912(a)(1).

5

Form SSA-827 serves as a claimant’s written request to release information. SSA, POMS, DI 11005.055,

(October 9, 2014).

6

SSA, POMS, DI 22505.001, B.2 (September 17, 2020). SSA will request medical records and follow-up between

10 and 20 calendar days if it does not receive them. 20 C.F.R. § 404.1512(b)(1) and 416.912(b)(1). See also

42 U.S.C. §§ 423(d)(5)(B) and 1382c(a)(3)(H)(i).

7

Department of Health and Human Services, The Number of Practicing Primary Care Physicians in the United

States, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, ahrq.gov (July 2018) and American Hospital Association, Fast

Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2021 Edition, aha.org (January 2021).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 2

Table 1: Sources of SSA Medical Records - FYs 2017 Through 2019

Source of Medical Records

FY 2017

Number and Percent

of Medical Records

FY 2018

Number and Percent

of Medical Records

FY 2019

Number and Percent

of Medical Records

Health Care Organization,

such as Hospitals and

Physicians

16,832,126 77.5% 16,496,321 78.3% 14,084,934 80.7%

Claimant Representative

8

2,299,553

10.6%

2,156,029

10.2%

1,403,692

8.1%

Consultative Examination

9

2,271,736

10.4%

2,092,081

10.0%

1,757,895

10.1%

Claimant

277,467

1.3%

276,571

1.3%

163,070

0.9%

Educational Facilities

10

50,881

0.2%

49,066

0.2%

42,421

0.2%

TOTAL

21,731,763

100%

21,070,068

100%

17,452,012

100%

The Social Security Administration’s Process for

Obtaining Medical Records

SSA pays approximately $500 million per year to obtain medical records by paper, Electronic

Records Express (ERE), and health IT.

11

Paper consists of medical records SSA obtains through regular mail or fax (or if dropped off

at an SSA office by a claimant or claimant representative.)

12

Paper records can take days,

weeks, or months for SSA to receive because manual processes are involved; most of the

time is spent waiting for records to arrive. This time involves:

o SSA calling, mailing, and/or faxing requests for records with a Form SSA-827;

13

o health care providers receiving requests, pulling records, and sending records to SSA;

o SSA scanning responses that are stored as unstructured data;

14

and

8

Individuals filing an application for Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance benefits or Supplemental Security

Income payments may appoint qualified individuals as representatives to act on their behalf in matters before SSA.

20 C.F.R. §§ 404.1705 and 416.1505, and SSA, POMS, GN 03910.020 (May 1, 2013).

9

SSA authorizes DDSs to purchase consultative examinations including medical examinations, X-rays, and

laboratory tests, when the existing records are insufficient to make a determination. POMS, DI 39545.120, A. (June

5, 2017).

10

Educational facility (such as school) records may contain medical information. SSA, POMS, DI 81020.040, B.3 (d)

(February 11, 2019).

11

SSA, Operations Analysis: Electronic Evidence Acquisition, p. 3 (April 2020).

12

If SSA employees receive medical evidence via email, Agency policy requires they inform the sender that email is

not secure and advise them to mail or fax copies of the records or use the ERE Website. SSA, POMS, DI 81020.060,

B. (June 7, 2011).

13

SSA, POMS, DI 22505.006, B.2 (March 15, 2017). For telephone requests, SSA will mail or fax the

Form SSA-827. SSA, POMS, 22505.030, B.1 (b)(1) (April 2, 2021).

14

Unstructured data cannot be easily organized using pre-defined structures. Examples specific to healthcare

include radiology images or text files, like a physician’s notes in the electronic health record. Healthcare Structured

vs. Unstructured Data, https://partners.healthgrades.com/blog/deep-data-dive-structured-and-unstructured-data-in-

healthcare-marketing (May 10, 2021).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 3

o SSA paying for records by individual check (see Appendix A for State payment rates for

medical records obtained via paper or ERE.)

ERE allows organizations to upload records directly into claimants’ unique SSA electronic

folders

15

via SSA’s secure Website using a barcode SSA provides.

16

According to SSA, it

receives ERE medical records faster than paper records because of the electronic exchange

process for receiving the records. However, SSA does not track the time from when it

requests and receives ERE records.

Health IT uses an array of technologies—such as electronic health records and health

information exchange networks

17

—to record, store, protect, retrieve, send, and receive

medical records securely over the Internet. SSA requests and receives health IT records in

seconds or minutes because of the automated process, which involves an SSA system:

identifying health IT partner(s);

sending an electronic request and Form SSA-827 via a health data exchange network;

receiving health IT records as both structured

18

and unstructured data from health IT

partners; and

o electronically paying the federally approved rate of $15 per successful transaction.

In August 2008, SSA partnered with a medical provider to pilot a prototype application called

Medical Evidence Gathering and Analysis through Health Information Technology (MEGAHIT)

and developed standards for the patient-authorized release of health IT records.

19

SSA uses

MEGAHIT to automatically request, receive, and analyze health IT records from partner

organizations. SSA’s health IT partners consist of healthcare organizations, health information

exchanges, and other Federal agencies. MEGAHIT’s data analytics function uses a set of

business rules based on SSA’s Listing of Impairments.

20

MEGAHIT business rules include

rules for cancers, blindness, amputations, transplants, etc. This functionality analyzes the

medical information by looking at diagnosis codes, treatment codes, and other factors and alerts

the examiner to significant information. For example, MEGAHIT creates an alert, such as

15

SSA’s electronic folder contains a claimants’ disability information. SSA, POMS, DI 81001.005, B

(September 11, 2020).

16

SSA, Use Electronic Records Express to Send Records Related to Disability Claims, Publication 05-10046

(September 2020). Some providers use vendors to release records to SSA via secure file transfers or web services.

17

A health information exchange network allows health care organizations to appropriately access and securely

share patients’ medical information electronically.

18

Structured data can be found in any healthcare database and may include details like customer names and contact

information, lab values, patient demographic data and financial information. Healthcare Structured vs. Unstructured

Data, https://partners.healthgrades.com/blog/deep-data-dive-structured-and-unstructured-data-in-healthcare-

marketing (May 10, 2021).

19

SSA, OIG, Health Information Technology Provided by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and MedVirginia, A-

01-11-11117 (October 2011).

20

SSA’s Listing of Impairments describes, for each of the major body systems, impairments that the Agency

considers to be severe enough to prevent an individual from performing gainful activity, regardless of his or her age,

education, or work experience. 20 CFR §§ 404.1525(a) and 416.925(a). An impairment medically equals a Listing if

it is at least equal in severity and duration to the criteria of any listed impairment. 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.1526(a) and

416.926(a). If a condition meets or medically equals a Listing, and the claimant is not performing substantial gainful

activity, SSA will find the claimant disabled. 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.1520(b) and (d) and 416.920(b) and(d). SSA, POMS,

DI 24508.010 (February 13, 2018); DI 24508.005 (April 2, 2018); and DI 34000.000 (July 22, 2021).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 4

“. . . preliminary computer analysis indicates that ‘specific listing’ should be considered in this

case.” As additional health IT documents are added to the claimant’s electronic folder, the rules

are rerun across both the new and existing health IT documents looking for matches. See

Figure 1 for a flowchart of SSA’s processes to obtain and analyze medical records.

Figure 1: SSA’s Processes to Obtain and Analyze Medical Records

Benefits of Health Information Technology

As shown in Table 2, SSA makes disability determinations quicker with health IT records; and a

faster allowance determination by SSA means disabled beneficiaries have quicker access to

cash benefits and health care coverage. In a prior review, we concluded the wait for benefits

affected at least one aspect of a disability claimant’s life, such as their finances, access to

medical care, and relationships.

21

21

SSA, OIG, Congressional Response Report: Impact of the Social Security Administration's Claims Process on

Disability Beneficiaries, A-01-09-29084 (September 2009).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 5

Table 2: Comparison of Initial Case Processing Times with and Without Health IT

Records for FYs 2017 Through 2020

FY

Average Processing

Time for Cases

Without Health IT

Records (Days)

Average Processing

Time for Cases with at

Least One Health IT

Record (Days)

Average Processing

Time for Cases with

Only Health IT

Records (Days)

2017

89

79

59

2018

91

82

61

2019

95

88

64

2020

107

101

70

Prior Report on Health Information Technology

In a 2015 audit, we found that despite challenges, SSA continued to expand the number of

health IT partners and had 38 health care partners in 30 States and the District of Columbia. In

addition, the DDS reported they were generally satisfied with MEGAHIT; however, some

suggested SSA improve formatting for health IT records to emphasize dates of treatment and

omit retracted or repetitive information. We found that MEGAHIT received health IT records

19 days faster than paper and ERE medical records.

22

We made four recommendations that

SSA agreed with and implemented; see Appendix B.

Scope and Methodology

We reviewed SSA’s processes to obtain medical records; efforts to expand health IT; and use of

data analytics to evaluate medical records. We identified a population of 1.7 million individuals

who had a health IT request in SSA’s electronic folder with a case establishment date in

Calendar Years 2016 through 2018. From this population, we analyzed a random sample of

275 cases. We also interviewed managers and staff at the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (HHS-

ONC) about the nation-wide expansion of electronic health records. See Appendix C for our

scope and methodology.

RESULTS OF REVIEW

Although SSA has generally met its targets for increasing the use of health IT to obtain medical

records, the Agency still receives most of the medical records it needs to make disability

determinations in paper or ERE format—not as health IT, see Figure 2. (See Appendix D for a

timeline of SSA’s efforts to electronically obtain and analyze medical records.) Since FY 2018,

SSA has experienced a decreasing trend in adding new health IT partners. SSA reduced the

number of staff and contractors involved in adding new health IT partners, and the Agency did

not fully fund projects to increase electronic medical evidence. In addition, prospective partners

must be willing and able to meet SSA’s technical requirements, including an ability to send

sensitive medical records, acceptance of SSA’s authorization form to release records to the

22

SSA, OIG, The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of Health Information Technology, A-01-13-13027, p 10

(May 2015).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 6

Agency (Form SSA-827), as well as medical industry-wide differences in patient-identifying data

fields. In October 2021, SSA informed us it was increasing its efforts by working on

Memorandums of Understanding with three entities to exchange health IT records with over

30 large health IT organizations.

Figure 2: Number and Type of Medical Records - FYs 2016 Through 2020

9,372,392

9,200,753

8,656,254

6,814,388

7,056,697

5,073,931

6,980,627

6,885,301

5,864,376

6,004,051

455,174

650,746

954,766

1,406,170

1,560,916

0

1,000,000

2,000,000

3,000,000

4,000,000

5,000,000

6,000,000

7,000,000

8,000,000

9,000,000

10,000,000

FY 2016 FY 2017

FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020

Number of Records

Fiscal Years

Paper ERE Health IT

34%

3%

4%

6%

10%

11%

63%

41%

55%

42%

52%

42%

48%

41%

48%

Addi

tionally, SSA has had limited success in expanding its data analytics of medical records to

assist adjudicators in determining whether claimants are disabled. As of FY 2021, SSA was

exploring options to automatically analyze all medical record formats (paper, ERE, and health

IT).

The Agency’s Evolving Strategy for Obtaining and

Analyzing Medical Records

The Agency’s 2014 Open Government Plan included a major health IT initiative to reduce the

time to obtain medical records needed to support disability determinations and manage the

information more efficiently. Per SSA’s plan, using health IT provides:

a fully automated request and receipt process for medical evidence;

more complete and standards-based medical records; and

faster disability decisions using extensive rules-based decision support.

SSA’s plan was to continue its outreach efforts in FYs 2014 through 2016 to include additional

medical providers and collaborate on setting government-wide health IT policy, and by

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 7

participating in advisory panels, workgroups, and task forces to ensure SSA’s unique business

needs were included in national standards and policies.

23

In FY 2010, SSA set a baseline target: to increase the percentage of disability cases evaluated

using health IT.

24

In FY 2014, SSA modified the target: to increase the percent of initial

disability claims processed with health IT medical records. The percent of initial claims with

health IT grew from 3 to 14 percent, see Table 3.

Table 3: Increase the Percent of Initial Claims Processed with Health IT Medical Evidence

FYs 2014 Through FY 2017

25

FY

Target for Initial Claims

with Health IT

Percent of Initial

Claims with Health IT

Target Met

2014

2.5%

3.0%

Yes

2015

6.0%

6.1%

Yes

2016

8.0%

9.6%

Yes

2017

12.0%

14.0%

Yes

In FY 2018, SSA modified its performance target again, by combining health IT with ERE

medical records because it determined the health IT performance measure did not accurately

represent its performance in reference to the rate of electronic evidence received. However,

health IT is a fully automated process from the request and receipt of the medical records;

whereas ERE involves the manual request of the records and receipt is through fax or requires

a manual upload to SSA’s system using a bar code.

SSA met its new target for combined health IT and ERE medical records in FYs 2018

26

and

2019 but not in 2020 (see Table 4).

23

SSA, Open Government Plan 3.0 Plan Milestones and Completion Report (June 2014) and SSA, Annual

Performance Report Fiscal Years 2017 - 2019 (February 2018).

24

SSA, Annual Performance Plan for Fiscal Year 2015, Revised Performance Plan for Fiscal Year 2014 and Annual

Performance Report for Fiscal Year 2013, p. 29 (March 2014).

25

SSA’s Annual Performance Report Fiscal Years 2017 – 2019, p. 44 (February 2018).

26

In June 2018, SSA looked into the feasibility of outsourcing the collection of medical evidence to capable industry

vendors on a nation-wide basis

established a panel to determine which vendors

could meet its needs. However, after this review, SSA leadership preferred to consider other alternatives based on

emerging technologies and advances in patient health and took no procurement action related to this effort. SSA

could not provide us with a cost analysis to support this decision. SSA,

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 8

Table 4: Improve the Disability Process by Increasing the Percentage of Medical

Evidence Received from Health IT and ERE

FYs 2018 Through 2020

27

FY

Target for Initial

Claims with

Health IT or ERE

Percent of Initial

Claims with

Health IT

Percent of Initial

Claims with ERE

Percent of Initial

Claims with

Health IT and

ERE

Target

Met

2018

45.0%

6.0%

42.0%

48.0%

Yes

2019

50.0%

10.0%

42.0%

52.0%

Yes

2020

60.0%

11.0%

41.0%

52.0%

No

The actual percent of initial claims with health IT records in FYs 2018 through 2020 (Column 3,

Table 4 – 6, 10, and 11 percent) was less than the FY 2017 level (Column 3, Table 3 –

14 percent). Therefore, SSA’s updated strategy did not help it increase the number of health IT

records it received. According to SSA, several factors impacted its ability to meet its FY 2020

target, such as an increase in faxed (non-electronic medical evidence) submissions by

7.26 percent after 3 consecutive years of decreases and setbacks due to the COVID-19

pandemic (that is., Health IT partners redirecting resources).

In its Annual Performance Report for Fiscal Years 2019-2021, SSA’s key initiative was to

Expand Access to Electronic Medical Evidence and it no longer included a specific target for just

health IT records.

We depend on healthcare providers to provide medical records we need to

determine whether a claimant is disabled. Expanding the use of electronic

medical evidence allows disability adjudicators to easily navigate the record to

identify pertinent information, makes it easier for medical providers to submit

evidence, and provides our agency with additional opportunities to use data

analytics to improve the disability process.

28

Challenges the Agency Faces in Obtaining and Analyzing

Health Information Technology Medical Records

The HHS-ONC reported that, in FY 2017, 80 percent of office-based physicians and 96 percent

of non-Federal acute care hospitals used certified electronic health records.

29

Although medical

providers have electronic health records, they may not be able to send those records to SSA.

27

SSA, Annual Performance Report Fiscal Year 2020, p. 20 (January 2021) and Annual Performance Report, Fiscal

Years 2019-2021, p. 18 (February 2020). SSA’s health IT goal for FY 2020 was established before the COVID-19

pandemic.

28

SSA Annual Performance Report, Fiscal Years 2019-2021, p. 18 (February 2020). SSA’s target for electronic

medical evidence includes both ERE and health IT.

29

Health IT Dashboard, United States Health IT Summary, healthit.gov (December 7, 2020). The HHS-ONC

Certification Program assures that a system meets the technological capability, functionality, and security

requirements adopted by the Department of Health and Human Services. The HHS-ONC tracks the adoption of

electronic health records for non-Federal acute care hospitals and office-based physicians in the United States, which

“. . . . comprise a majority of those providers eligible for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Promoting

Interoperability Program, and are the primary source of health care for many Americans.”

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 9

The HHS-ONC reported that, in both 2015 and 2017, “. . . about only 1 in 10 physicians

engaged in all 4 domains of interoperability,” which is the ability to send, receive, find, and

integrate health information received from outside sources and use that information to inform

clinical decision-making.

30

Additionally, the “. . . most frequent reported barrier to electronic

exchange was difficulty exchanging data across different [electronic health records] vendor

platforms.”

31

In February 2009, the President signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

into law.

32

The Act provided $40 million to SSA for health IT research and activities to facilitate

the adoption of electronic medical records, including the transfer of funds to the Supplemental

Security Income Program to carry out activities under the Social Security Act. SSA used over

$17 million of these funds to form health IT partnerships. However, according to the HHS-

ONC,

33

since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds have been completely

distributed, there are no financial incentives for organizations to offset the cost of implementing

an electronic records process.

34

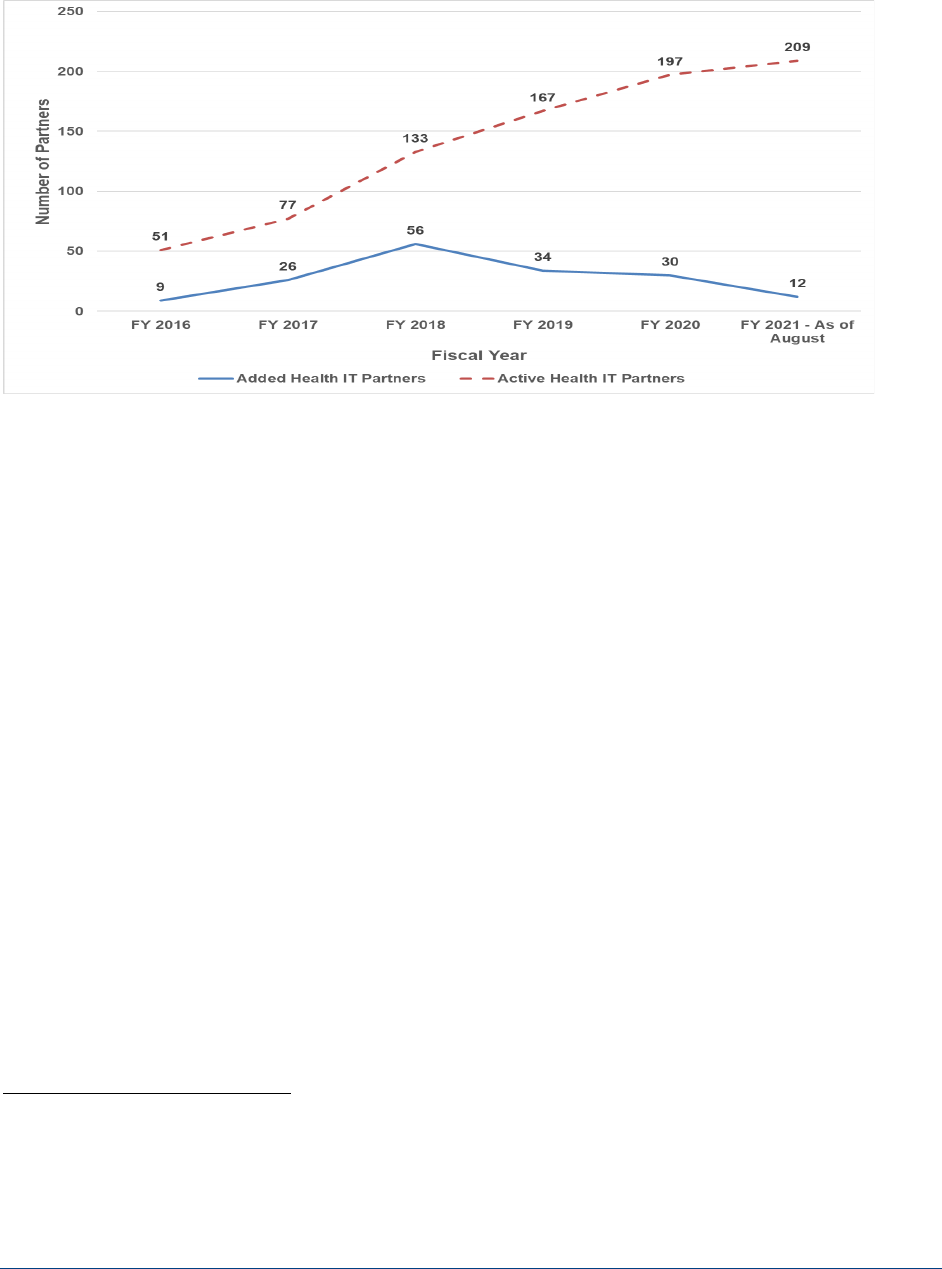

As of August 2021, SSA had added 12 new partners for a total of 209 health IT partners, that

comprised more than 26,000 health care providers in 49 States.

35

However, since FY 2018,

SSA has experienced a downward trend in adding new partners (see Figure 3). SSA informed

us that “There is no way for us to know for certain for FY 2019 [why fewer partners were added].

Adding partners is not a unilateral decision as prospective partners must be willing and able to

partner with us, and each has their own reasons for pursuing or not pursuing this

relationship . . . For FYs 2020 and 2021, we know that the COVID-19 pandemic was the main

factor. Prospective partners reacted to the pandemic and changed their priorities, as with the

rest of the health care industry.”

30

Vaishali Patel, MPH PhD; Yuriy Pylpchuk, PhD; Sonal Parasrampuria, MPH; and Lolita Kachay, MPH,

Interoperability among Office-Based Physicians in 2015 and 2017, The Office of the National Coordinator for Health

Information Technology, ONC Data Brief, No. 47, p. 1 (May 2019).

31

Yuriy Pylpchuk, PhD; Christian Johnson, MPH; Vashali Patel, PHD MPH, State of Interoperability among U.S. Non-

federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2018, The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, ONC

Data Brief, No. 51, p. 4 (March 2020).

32

Pub. L. No. 111-5, 123 Stat. 115, 186 (2009).

33

The HHS-ONC—in the Department of Health and Human Services—is the principal Federal entity charged with

coordinating nation-wide efforts to implement and use the most advanced health IT and the electronic exchange of

health information.

34

See Appendix E for a summary of Federal legislation that promotes health IT expansion.

35

SSA does not have health IT partners in Maine. According to SSA, its Health IT Outreach Team contacted

healthcare providers and health information organizations in Maine as far back as 2014. Many of these organizations

have not been able to meet its clinical information requirements or were not interested in sharing electronic health

information with SSA.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 10

Figure 3: Number of Health IT Partners

SSA identifies potential partners from multiple sources including health IT conferences, SSA

regional office staff, DDS referrals, and direct referrals. According to SSA, “Outreach and

relationships are essential to our success. Because we do not have financial incentives, such

as grants, to help healthcare organizations who wish to connect with us, we must build and

maintain relationships with partners, technology vendors, and the DDS.”

36

SSA informed us

that it could onboard approximately 50 partners in an FY, assuming it can get that many to

agree to partner with SSA.

According to SSA, in FY 2021, it had eight staff working on health IT outreach and one subject

matter expert focused on developing strategies to expand health IT. However, around 2018,

when SSA was bringing more partners on board (as seen in Figure 3), it had more staff working

on outreach. Staff used to range from 8 to 10 (4 or 5 full-time employees and 4 or 5

contractors). The most was 12 (8 full-time employees and 4 contractors). In October 2021,

SSA informed us that it was re-starting its efforts to expand health IT and its overall strategy is

to add two more experts. The experts will advise the Agency on further developing health IT

strategies to increase health IT medical records. SSA stated it will continue partnering with

organizations that use Epic

37

software and the eHealth Exchange network, but that it was

developing new strategies for expanding the health IT records beyond this. SSA prioritizes

adding partners who use Epic electronic health record software because Epic provides broad

support for the data elements SSA needs to make disability determinations. According to SSA,

36

SSA, Office of Systems, Systems F.A.C.T.S. – January 2020, Health IT: HITting a Home Run, p. 1 (January 2020).

DDSs are generally State-run agencies that make disability determinations for SSA using the Agency’s regulations,

policies, and procedures; 42 U.S.C. §§ 421 ((a)(2) and 1383b (a).

37

Academic medical centers, community hospitals and other health care providers use Epic electronic health record

software to store patients’ records.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 11

“Epic is … an early adopter of the eHealth Exchange,

38

which creates a natural synergy as it is

the primary network that we use to onboard new organizations.”

Challenges with Obtaining Sensitive Records

Some potential health IT partners restrict sharing health records for anyone under age 18, while

others cannot provide such sensitive records as substance abuse and mental/behavioral

records. According to the HHS-ONC, “. . . because of State or local privacy and security laws,

sensitive records may not be sent through Health IT.” The HHS-ONC has set the minimum

clinical requirement for sharing health information electronically. Many healthcare

organizations, along with their associated electronic health record systems, look to the HHS-

ONC to establish additional standards and specifications to enable electronic sharing of more

types of clinical information electronically. According to the HHS-ONC, the basic requirements

to expand data elements should come online over the next few years.

From our 275-case sample, we identified 13 unsuccessful MEGAHIT requests for sensitive

records. For instance, on August 24, 2018, MEGAHIT requested a Colorado child’s speech

therapy records. The partner’s system responded with “no patient match.” After reviewing

SSA’s electronic records for this claimant, we could not determine why MEGAHIT’s response

was unsuccessful. However, the claimant was 3- years-old when the application was filed. On

October 2, 2018, SSA mailed a follow-up request and received the medical records via paper

(not health IT) on October 5, 2018. Instead of receiving the records via health IT on August 24,

2018 when it initially requested them, it took 42 days for SSA to receive the records.

Challenges with the Agency’s Authorization Form to Obtain

Health Information Technology Records

SSA has also experienced challenges with health record providers not accepting its Form SSA-

827. Some health IT partners:

only accept Form SSA-827s with a wet signature or eAuthorization;

will only release records that are dated before the date the claimant signed the Form SSA-

827;

will not release records if the Form SSA-827 signature is older than 60 days;

require a signature on their own release form in addition to the Form SSA-827; and

may ask for an updated Form SSA-827 signed by someone applying on the claimant’s

behalf.

In November 2019, SSA issued a reminder for staff to review Forms SSA-827 to ensure they

are correctly completed, legible, signed, and dated before transferring the case to the DDS.

39

MEGAHIT will not generate a request if the Form SSA-827 is not in the electronic folder within

38

The eHealth Exchange is the largest healthcare information network in the country and is active in all 50 States.

The eHealth Exchange is a network connecting Federal agencies and non-Federal healthcare organizations so

medical data can be exchanged nationwide to improve patient care and public health (ehealthexchange.org

[May 11, 2021]).

39

SSA, AM-19031 REV (November 20, 2019).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 12

5 hours of the system first searching for it, is restricted, or is expired. If the Form SSA-827

prevents an automated MEGAHIT transaction, the system will generate a health IT response

document alerting staff there is an issue, and the request for health IT will not process.

For our sample, we concluded MEGAHIT was working properly because the system generated

an alert notifying staff of invalid information on the Form SSA-827. For example, we identified

six cases where MEGAHIT generated a health IT response document alerting staff there was an

issue with Form SSA-827. For these six cases, MEGAHIT did not send a request for health IT

medical records because it could not identify a Form SSA-827 in the file (two cases), the health

IT partner (Department of Veteran’s Affairs) only accepts wet signatures (three cases), and the

wet-signature was more than 9-months old (one case). For the case where the wet-signature

was too old, the evidence showed that an SSA employee initiated a user triggered request for

health IT records, but MEGAHIT prevented the request because the Oregon claimant’s

signature on Form SSA-827 was more than 9 months old. SSA obtained an updated Form

SSA-827 and then requested the medical records. To mitigate these Form SSA-827 issues,

SSA plans to develop and implement a tool sometime after FY 2021 to automatically validate

paper Forms SSA-827 and flag those with invalid inputs.

Challenges Matching Patient-identification Information

Another obstacle limiting the expansion of health IT records is differences in patient-identifying

data between SSA and its partners. When SSA requests records, it provides its health IT

partners with the claimant’s name, date of birth, Social Security number, address, and gender.

However, the partner decides how to use the data to identify the claimant in its system. To

avoid disclosing the wrong individual’s health record, partners typically provide electronic

records for only exact data-request matches.

From our sample, we identified 31 MEGAHIT requests that were unsuccessful because of

differences between partner and SSA data. For all cases, SSA needed to follow up with a

manual request to obtain the medical records. For example, on March 24, 2017, MEGAHIT

requested a Kentucky claimant’s records. The health IT partner responded with a “no patient

match” document. On April 24, May 11, and May 26, 2017, SSA followed up by manually

triggering MEGAHIT requests and received the same “no patient match” response. On

May 26, 2017, SSA faxed a request for records. On June 5, 2017—73 days after the initial

MEGAHIT request—SSA received records from the partner. The initial MEGAHIT requests

failed because the individual’s first name in SSA’s system, Jane Lyn, did not match that in the

partner’s system, Janelyn.

SSA has been an active partner with the HHS-ONC in creating and setting national

interoperability standards. In 2018 and 2020, SSA participated in HHS-ONC organized patient

matching working sessions to address the industry-wide issue of differences in patient-

identifying data. According to the HHS-ONC, it and its Federal partners are working on a

Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement, which is mandated by the 21

st

Century

Cures Act.

40

Once finalized, this Framework and Agreement should help enable nationwide

exchange of electronic health information across disparate health information networks, and will

outline a common set of principles, terms, and conditions. HHS-ONC’s goal is to have the

Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement finalized in 2022.

40

21

st

Century Cures Act, Pub. L. No. 114-255, § 4003, 130 Stat. 1033, 1165 (2016).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 13

Challenges in Analyzing Medical Evidence Electronically

A challenge SSA faces in enhancing its data analytics is MEGAHIT’s limitation of analyzing only

structured health IT data. SSA receives both structured and unstructured data from health IT

partners. Per SSA, “. . . the more structured documents (non-image) we receive from partners,

the easier it is to execute our business rules…We encourage our partners to provide as much

structured dat[a] or as many coded documents as possible.”

According to SSA, the number of business rules limits the extracts MEGAHIT can generate.

MEGAHIT generated an extract for 7.3 percent of the approximately 1.6 million health IT

records in FY 2020. In our sample review, MEGAHIT generated a health IT extract for 14 of

275 cases (5 percent). The extracts assist SSA disability examiners in making disability

determinations. While SSA has no technical barriers to adding more business rules, it has not

added new rules since 2020 and does not have plans to do so. Instead, in 2018, SSA began

testing a new application called Intelligent Medical-language Analysis GENeration (IMAGEN),

which would:

enable adjudicators to visualize, search, and more easily identify relevant clinical content in

medical records;

directly correlate clinical information from medical evidence to SSA’s disability impairment

listings; and

improve speed and consistency of medical determinations and decisions.

41

IMAGEN automates the analysis of medical record content, provides decisional support to

disability adjudicators, and will create efficiencies and new knowledge in disability case

processing and determinations by using:

optical character recognition to convert imaged documents into machine-readable text;

natural language processing to convert text into structured data;

machine learning and artificial intelligence to mine and model structured data to provide

intelligent insights based on historical claim outcomes; and

a user-interface to provide advanced search, filtering, alerting, annotation, charting,

explanation, and medical record summarization features.

Whereas MEGAHIT business rules are limited to analyzing structured health IT medical

evidence, SSA is designing IMAGEN to retrieve medical records (both unstructured and

structured) in the disability electronic folder and convert them into machine-readable formats.

As of August 2021, SSA continued to test and roll out IMAGEN at its offices and at State

disability determination services.

41

SSA, Office of Systems, Systems Talks, Connecting Through Conversations, IMAGEN (June 19, 2019).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) 14

The Agency’s Plan for Increasing Electronic Medical

Records for Fiscal Year 2021 and Beyond

As part of SSA’s IT planning for FY 2021 and beyond, in April 2020, SSA’s Deputy

Commissioner for the Office of Retirement and Disability Policy submitted a proposal to spend

$60.1 million over 5 years for electronic evidence acquisition. The proposal included plans to

explore and prototype options to automatically exchange all medical record formats—paper,

ERE, and health IT—and retrieve medical records from the most appropriate sources in real

time to reduce manual intervention, additional requests, and duplicate records.

42

SSA expects

this strategy will help it attain its targets of moving away from non-electronic records, decreasing

disability determination times, reducing customers’ burdens at claim filing, and reducing

acquisition costs. While board members of SSA’s Information Technology Investment Process

voted to approve the proposed investment, ongoing planning discussions resulted in an overall

program budget reduction. According to SSA, the project’s budget was cut, and therefore, it has

been scaled back. Depending on SSA’s FY 2022 budget, the project will be restarted or left on

pause.

In October 2021, SSA informed us it was jump-starting its efforts to expand health IT. SSA was

working on Memorandums of Understanding with 3 entities to exchange health IT records with

over 30 large health IT organizations. SSA was also planning to:

analyze geographic variations to identify areas of poor coverage to enable outreach and

onboarding of new sources to increase electronic medical records;

identify large non-electronic providers to try to transition them to providing electronic medical

records;

measure medical source performance (response rates, content quality, etc.) to forecast

growth and inform outreach strategy; and

implement automated notifications based on pre-defined conditions (for example, a decline

in medical source response rate, a decline in medical source volume, etc.;) to actively

engage partners.

Should additional funding become available, SSA plans to evaluate acquiring structured medical

evidence directly from claimants, bypassing the need for lengthy provider onboarding

processes.

RECOMMENDATION

We recommend SSA intensify efforts to increase the number of health IT partners.

42

SSA, Operation Analysis Electronic Evidence Acquisition, (April 2020).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342)

APPENDICES

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) A-1

– THE SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION’S

MEDICAL RECORD PAYMENT RATES

The Social Security Administration (SSA) will pay a fee for medical records obtained from health

care organizations.

1

For health information technology (health IT) records, SSA pays a $15 flat

rate for each successful transaction. For medical records obtained via paper (mail or fax) or

Electronic Records Express, SSA pays $1 or more based on actual State payment rates.

2

See

Table A–1.

Table A–1: State Payment Rates for Medical Records Obtained via Paper or Electronic

Records Express as of June 2020

State General Payment Rates Medical Records

Alabama

Flat fee of $18.00

Alaska

Average payment of $35.00 with a range $30.00-$50.00

Arizona

Flat fee of $13.15

Arkansas

Flat fee of $15.00

California

Range $14.05 to $21.60 dependent on number of pages. Medical records and narrative

reports from the treating physician or other medical source pay the lesser of: $35.00

(maximum) or billed amount

Colorado

Flat fee of $22.00 (additional $8 payment if received within 5 days of request). $30.00 for a

narrative

Connecticut

Payment of $20, if records received in 30 days or less and no payment for records received

after 30 days

Delaware

Flat fee of $15.00

District of

Columbia

Payment of $25.00, if records received within 20 days; $10.00 if records received after

20 days; and no payment if records received after 60 days

Florida

Flat fee of $14 for all medical evidence. Teacher and speech-language pathologist

questionnaires are a flat rate of $16.00.

Georgia

Payment of $15.00; $10.00 per State of Georgia Health Department’s service time; and

$25.00 for completion of Mental Impairment Questionnaire and Denver Childhood

Questionnaire

Guam

Payment of $35.00; $1.00 for Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands first page and

$.25 page thereafter; and $25 for Samoa

Hawaii

Payment of $15.60 and $31.20 for completion of psychiatric questionnaire

Idaho

$15.00 for records or narrative reports, or up to $15.00 if billed less than that

Illinois

Flat fee of $20.00

Indiana

Payment of $14.00 for copies of medical records; $40 completion of mental questionnaire;

and $25.00 for other questionnaires

Iowa

Payment of $35.00 (or as billed if less than $35.00) and for search fee “no records found”

Kansas

$30.00 per response

Kentucky

Payment up to $15.00

Louisiana

Flat fee of $20.00

Maine

Flat fee of $15.00 (or as billed if less than $15.00)

1

SSA, POMS, DI 11010.545 (February 14, 2017).

2

Vermont will pay $20 for medical records only if records are received within 16 days of request date.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) A-2

State General Payment Rates Medical Records

Maryland

Payment of $15.00 for copies of pertinent history, physical, and treatment records; $35.00 for

abstract and physical from treating physician, the physical examination should be within

approximately the last 6 months; and $26.00 for abstract and evaluation (within

approximately last 6 months) from treating licensed health care provider such as

Occupational Therapist, Physical Therapist, Licensed Clinical Social Worker

Massachusetts

Payment of $15.00 for report to physician; $10.00 for report to hospital (additional

$10 payment if received within 15 days of request)

Michigan

Flat fee of $15.00

Minnesota

Payment of $35.00 for all medical or psychological records; $10.00 for chiropractic,

audiology, or physical therapist records; and $0 for school, prison, Veterans Administration,

or other Government agency records

Mississippi

Payment of $14.00; $16.00 for mental health centers; and $31.00 for functional data reports

from mental health centers

Missouri

Payment of $26.06 plus $0.60 per page for paper records plus $24.40 if records maintained

off-site; $26.06 + $0.60 per page or $114.17 maximum, whichever is less, for electronic

records; and $26.06 plus $1.00 per page for Microfilm

Montana

Payment of $10.00 for hospital and schools and $25.00 for doctors, clinics, mental health

centers, private entities (payments limited by state law)

Nebraska

Payment of $20.00 for medical records plus $0.50 per page with specific sources having a

max of $100.00; Howard County Hospital - $100 cap up to 500 pages—anything over

500 pages, State will pay $0.50 per page; and $30.00 maximum for Narrative reports

Nevada

Flat fee of $15.00

New Hampshire

Payment of $1.00 per page up to $15.00 maximum for a copy of existing record and

$16.00 for narrative or completion of forms

New Jersey

Flat fee of $10.00

New Mexico

Flat fee of $18.75, (will pay less if billed less).

New York

Flat fee of $10.00

North Carolina

Flat fee of $15.00

North Dakota

Payment of $20.00 for the first 25 pages, then $0.75 for each additional page for paper

records; and $30 for first 25 pages, then $0.25 for each additional page for electronic records

Ohio

Payment of $15.00 for hospital records and $20.00 for doctor records

Oklahoma

Flat fee of $18.00

Oregon

Payment of $75.00 for full narrative reports more than 2 pages; $35.00 for brief narrative

reports; $18.00 for hospitals, doctors and copy companies, 1-10 pages and $0.25 for pages

11-20 and $0.10 for pages 21 and greater with a total maximum fee of $22.50; and $18.00 if

there is no indication of the number of pages (additional $5 payment if received within 7 days

of request)

Pennsylvania

Flat fee of $29.19

Puerto Rico

Flat fee of $25.00 for all records from non-government entities received within 40 days from

original request date

Rhode Island

Payment of $10.00 (additional $5 payment to hospitals if received within 15 days of request);

and $0 for hospitals at the reconsideration level

3

South Carolina

Flat fee of $20.00

South Dakota

Payment of $11.79 for first 25 pages and $.50 for each additional page to a maximum of

$35.00; and $25 for narrative reports

Tennessee

Payment of $20.00 for medical records and $0 for school records

Texas

Flat fee of $18.00

3

If a claimant disagrees with the initial disability determination, he/she can appeal it. 20 C.F.R. § 404.900(a) and

416.1400(a).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) A-3

State General Payment Rates Medical Records

Utah

Payment of $15.00 for copy of records; $28.00 for written summary within 12 days; and

$0 for records received after 60 days and for records from schools or Government agencies

Vermont

A provider cannot charge for a copy of a disability applicant’s medical records. Payment of

$20 expedite fee is paid if the records are sent and the invoice is dated within 16 days of

request date

Virginia

Flat fee of $15.00

Washington

Payment of $22.00 for photocopied records up to 20 pages, $.50 per page beyond 20 pages

and $22 search fee for “no records found”

West Virginia

Flat fee of $11.00

Wisconsin

Flat fee of $26.00

Wyoming

Payment of $15.00 for hospital records; $25 for doctors/clinic and child development centers;

and $0 for public school records

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) B-1

– PRIOR REPORT RECOMMENDATION STATUS

In our May 2015 report, The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of Health Information

Technology, we concluded that, despite challenges, the Agency continued expanding health

information technology (IT).

1

Table B–1 shows the status of the recommendations.

Table B–1: Prior Audit Recommendation Status

Recommendation Status/Resolution

Continue to solicit, on a regular basis, disability

determination services’ (DDS) user feedback in

Medical Evidence Gathering and Analysis

through Health Information Technology

(MEGAHIT) enhancements

In December 2015, the Social Security Administration

(SSA) implemented a communications plan that collects

and monitors recommendations from the regions/DDS’ via

surveys and a discussion board. SSA will continue

conducting periodic surveys to solicit feedback.

We obtained and reviewed documentation of

11 enhancements SSA made to MEGAHIT software.

Enhance procedures to maintain and update

MEGAHIT partner data, such as addresses.

As of April 2016, SSA was holding monthly meetings with

health IT partners to allow for partner updates as needed.

We obtained and reviewed SSA’s health IT onboarding

flowchart, its communications plan, and the call script

SSA’s employees follow for reaching out and obtaining

information from health IT partners.

Enhance methods to improve the use of

information received via health IT.

As of October 2016, SSA was implementing a process to

obtain recommendations from health IT partners and meet

regularly to discuss enhancements.

1

SSA, OIG, The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of Health Information Technology, A-01-13-13027

(May 2015).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) B-2

Recommendation Status/Resolution

Increase health IT partners—taking advantage of

nation-wide Federal efforts led by Health and

Human Services’ Office of the National

Coordinator for Health IT.

SSA coordinates with the Health and Human Services’

Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (HHS-

ONC). In addition, SSA collaborates with the Departments

of Veterans Affairs and Defense on outreach to potential

new health IT partners. SSA also participates in

public/private workgroups to ensure that its business

needs are considered and incorporated into national

policies and standards; and to gather healthcare

organization contacts to partner with SSA.

We obtained active partner information from SSA’s

internal website and determined what year the partner was

added as a participant in the health IT network. Since our

2015 report, SSA added 171 health IT partners.

We interviewed staff at the HHS ONC and reviewed

information on issues, such as inoperability, with

increasing health IT records.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) C-1

– SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY

To accomplish our objective, we:

Reviewed applicable sections of the Social Security Act as well as the Social Security

Administration’s (SSA) regulations, rules, policies, and procedures.

Reviewed prior SSA Office of the Inspector General and Government Accountability Office

reports related to electronic medical records.

Analyzed actions SSA took to implement recommendations from our May 2015 report on

The Social Security Administration’s Expansion of Health Information Technology,

A-01-13-13027.

Reviewed information on SSA’s procedures to obtain medical records and use of data

analytics to evaluate medical records as well as the sources and quantity of medical

records.

Examined SSA’s health information technology (health IT) performance and strategic

targets.

Interviewed employees at the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the

National Coordinator for Health IT, about the nation-wide expansion of electronic health

records.

Interviewed an SSA subject-matter expert on increasing electronic medical evidence.

Obtained SSA’s payment rates to States for medical records.

Obtained a file of 1,700,177 individuals whose electronic folder indicated SSA requested

health IT records in Calendar Years 2016 through 2018. We randomly sampled 275 cases

1

and:

o analyzed health IT requests on case determinations and case adjudication levels;

determined whether SSA’s Medical Evidence Gathering and Analysis through Health

Information Technology (MEGAHIT) requests were successful;

verified that SSA partners responded to MEGAHIT requests an average of less than

1 day; and

calculated case processing times.

1

To conduct this review, we used a simple random sample statistical approach. This is a standard statistical

approach used for creating a sample from a population completely at random. As a result, each sample item had an

equal chance of being selected throughout the sampling process, and the selection of one item had no impact on the

selection of other items. Therefore, we were guaranteed to choose a sample that represented the population, absent

human biases, and ensured statistically valid conclusions of, and projections to, the entire population under review.

Our sampling approach for this review ensures that our reported projections are statistically sound and defensible.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) C-2

We conducted our review between April 2020 and August 2021 in Boston, Massachusetts, and

Arlington and Falls Church, Virginia. We determined the data used for this audit were

sufficiently reliable to meet our audit objectives.

We assessed the significance of internal controls necessary to satisfy our objective. This

included an assessment of the five internal control components, control environment, risk

assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring. In addition, we

reviewed the principles of internal controls associated with our objective. We identified the

following components and principles as significant to the objective.

Component 5: Control Activities

Principle 10: Design Control Activities

Principle 12: Implement Control Activities

Component 5: Monitoring

Principle 16: Perform Monitoring Activities

The primary entity audited was the Office of Health Information Technology under the Deputy

Commissioner/Chief Information Officer, Systems. We conducted this performance audit in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require

that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a

reasonable basis for findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on

our audit objectives.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) D-1

– TIMELINE OF THE SOCIAL SECURITY

ADMINISTRATION’S USE OF HEALTH

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The Social Security Administration (SSA) began obtaining and analyzing health information

technology (health IT) medical records in 2008. Since then, the Agency has expanded its

efforts to electronically obtain and analyze medical records, see Table D–1.

Table D–1: Timeline of SSA’s Efforts to Electronically Obtain and Analyze Medical

Records

Year(s)

Status

2008

Medical Evidence Gathering and Analysis through Health Information Technology

(MEGAHIT) system implemented to obtain and analyze health IT medical records.

2009

SSA partnered with MedVirginia—a coalition of not-for-profit hospitals and physicians—

to expand the use of health IT to exchange records through the Nationwide Health

Information Network.

2011-2015

SSA added 36 health IT partners (through February 2015).

1

2015

SSA expanded to 38 health IT partner organizations in 30 States and the District of

Columbia and identified ways of enhancing health IT case processing and data

analytics.

2017

From Fiscal Years 2014 through 2017, SSA met its performance target to increase the

percent of initial disability claims processed with health IT medical records.

2018

SSA began developing and testing the Intelligent Medical-Language Analysis

GENeration (IMAGEN) application, which would automate the analysis of medical

record content and provides decisional support to disability adjudicators.

SSA changed its performance target by combining health IT with Electronic Records

Express (ERE) medical records because it no longer believed the health IT

performance measure accurately represented its performance in reference to the rate

of electronic evidence received. (ERE allows organizations to upload records directly

into the claimant’s unique SSA electronic folder via SSA’s secure Website using a

barcode SSA provides.)

2020

SSA’s Office of Retirement and Disability Policy/Office of Disability Policy submitted an

electronic evidence acquisition proposal with a key priority to obtain medical records in

electronic and structured data formats.

2021

SSA leadership is reevaluating the electronic evidence acquisition proposal due to a

budget reduction. SSA expanded to 209 health IT partners in 49 States. SSA has no

plans to create any new targeted business rules to analyze health IT records in

MEGAHIT. SSA continued to test and rollout IMAGEN at its offices.

1

For a list of the health IT partners as of February 2015, see Appendix B in SSA, OIG, The Social Security

Administration’s Expansion of Health Information Technology, A-01-13-13027 (May 2015).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) E-1

–SUMMARY OF FEDERAL HEALTH

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LEGISLATION

Table E–1

Table E–1: Summary of Federal Health IT Legislation

Legislation Summary

Health Information

Technology for Economic

and Clinical Health Act

of 2009

1

Promoted the adoption and use of health IT and established the

Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the National

Coordinator for Health IT (HHS-ONC) and other committees in

support of this Act.

American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act of 2009

2

Paid approximately $1 million per contract for organizations to

implement electronic record systems and provided that up to

$40 million to be used by the Social Security Administration for health

IT research and activities to facilitate the adoption of electronic

medical records in disability claims.

Medicare Access and

Children’s Health Insurance

Program Reauthorization

Act of 2015

3

Established the national objective to achieve widespread

interoperability with certified electronic health records and required

the Department of Health and Human Services to measure the extent

to which this objective is being met.

21

st

Century Cures Act

4

Defines interoperability and mandated the HHS-ONC develop or

support a trusted exchange framework for trust policies and practices

and for a common agreement for exchange between health

information networks.

Coronavirus Aid, Relief,

and Economic Security Act

5

In an attempt to improve public health infrastructure, the HHS-ONC

will distribute $2.5 million in CARES Act funding to health information

exchanges to support public health uses of information from health

information exchanges. These networks make it easier for health

care organizations to exchange information, ranging from case

summaries to hospital discharge data.

1

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, Pub. L. No. 111-5, § 3001 (a), 123 Stat. 115,

230 (2009).

2

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-5, 123 Stat. 115, 186 (2009).

3

Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-10,

129 Stat. 87, 139 (2015).

4

21

st

Century Cures Act, Pub. L. No. 114-255, § 4003, 130 Stat. 1033, 1160 (2016).

5

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020).

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) E-2

Legislation Summary

21

st

Century Cures Act:

Interoperability, Information

Blocking, and the Office of

the National Coordinator

Health IT Certification

Program Final Rule

6

HHS-ONC is responsible for the implementation of key provisions in

Title IV of the 21

st

Century Cures Act that are designed to advance

interoperability; support the access, exchange, and use of electronic

health information; and address occurrences of information blocking.

7

6

21

st

Century Cures Act, 85 Fed. Reg. 25642, pp. 25642-25961 (2020).

7

Information blocking is a practice by a health IT developer of certified health IT, health information network, health

information exchange, or health care provider that, except as required by law or specified by the Secretary of Health

and Human Services as a reasonable and necessary activity, is likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of

electronic health information.

SSA’s Expansion of Health IT (A-01-18-50342) F-1

– AGENCY COMMENTS

SOCIAL SECURITY

MEMORANDUM

Date:

12/27/2021 Refer To: TQA-1

To:

Gail S. Ennis

Inspector General

From:

Scott Frey

Chief of Staff

Subject:

Office of the Inspector General Draft Report - "The Social Security Administration’s Expansion

of Health Information Technology to Obtain and Analyze Medical Records for Disability

Claims" (A-01-18-50342) — INFORMATION

Thank you for the opportunity to review the draft report. We agree with the recommendation.

Please let me know if I can be of further assistance. You may direct staff inquiries to

Trae Sommer at (410) 965-9102.

Mission: The Social Security Office of the Inspector General (OIG) serves the

public through independent oversight of SSA’s programs and operations.

Report: Social Security-related scams and Social Security fraud, waste, abuse,

and mismanagement, at oig.ssa.gov/report

.

Connect: OIG.SSA.GOV

Visit our website to read about our audits, investigations, fraud alerts,

news releases, whistleblower protection information, and more.

Follow us on social media via these external links:

Twitter: @TheSSAOIG

Facebook: OIGSSA

YouTube: TheSSAOIG

Subscribe to email updates on our website.