International Human

Resource Management

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page i

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page ii

International Human

Resource Management

SAGE Publications

London l Thousand Oaks l New Delhi

second edition

edited by

Anne-Wil Harzing

Joris Van Ruysseveldt

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page iii

© Anne-Wil Harzing and Joris van Ruysseveldt, 2004

First published 2004

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research

or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this

publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted

in any form, or by any means, only with the prior

permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of

reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms

of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms

should be sent to the publishers.

SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Olivers Yard

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B-42, Panchsheel Enclave

Post Box 4109

New Delhi 100 017

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 0 7619 4039 1

ISBN 0 7619 4040 5 (pbk)

Library of Congress Control Number available

Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page iv

Contents

Acknowledgements vii

Foreword by Nancy J. Adler viii

Contributor Biographies x

Abbreviations xvi

Introduction 1

PART 1 INTERNATIONALIZATION: CONTEXT, STRATEGY,

STRUCTURE AND PROCESSES 7

1 Internationalization and the international division of labour 9

Anne-Wil Harzing

2 Strategy and structure of multinational companies 33

Anne-Wil Harzing

3 International human resource management: recent developments

in theory and empirical research 65

Hugh Scullion and Jaap Paauwe

4 Human resource management in cross-border mergers and acquisitions 89

Günter K. Stahl, Vladimir Pucik, Paul Evans

and Mark E. Mendenhall

Part 2 HRM FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE 115

5 Cross-national differences in human resources and organization 117

Arndt Sorge

6 Culture in management: the measurement of differences 141

Laurence Romani

7 HRM in Europe 167

Christine Communal and Chris Brewster

8 HRM in East Asia 195

Ying Zhu and Malcolm Warner

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page v

Contents

vi

9 HRM in developing countries 221

Terence Jackson

PART 3 MANAGING AN INTERNATIONAL STAFF 249

10 Composing an international staff 251

Anne-Wil Harzing

11 Training and development of international staff 283

Ibraiz Tarique and Paula Caligiuri

12 International compensation and performance management 307

Marilyn Fenwick

13 Repatriation and knowledge management 333

Mila Lazarova and Paula Caligiuri

14 Women’s role in international management 357

Hilary Harris

PART 4 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS: A COMPARATIVE

AND INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE 387

15 The transfer of employment practices across borders in

multinational companies 389

Tony Edwards

16 Varieties of capitalism, national industrial relations systems

and transnational challenges 411

Richard Hyman

17 Industrial relations in Europe: a multi-level system in the making? 433

Keith Sisson

18 The Eurocompany and European works councils 457

Paul Marginson

Author Index 482

Subject Index 490

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page vi

Acknowledgements

So much has changed since the 1st edition. We cannot even begin to encompass

the changes which have occurred in our now ‘globalized’ world. However, the

nature of academic work has also changed considerably since the 1st edition of

this book was published in 1995. Internet access and email have transformed

our daily working lives. Internet access means having information at our

fingertips. However, it also means an increasing challenge in assessing the

relevance of all this information. The contributors of this book have done an

excellent job in sifting the wheat from the chaff. The use of email has made it

much easier to communicate with authors. While for the 1st edition, much of

our editorial work was done via fax or even personal meetings with the chapter

authors, the current edition was based on email contact alone (a lot of it!). This

has made it possible to involve authors from a far wider range of countries than

before.

Much has stayed the same as well. First, our philosophy that the book be

developed as a research-based textbook has remained constant. The book

reflects the characteristics of the transnational MNC in that we think it com-

bines the benefits of knowledge transfer (authors who are experts in their

field), integration (a coherent textbook) and local responsiveness (authors from

many different countries as well as chapters specific to Asia, Europe and Africa).

What never changes is the fact that for such an undertaking many people

deserve acknowledgements. First of all we would like to thank Arndt Sorge for

encouraging us to embark on a 2nd edition. If he had not spoken so convinc-

ingly about our duty to the field, this 2nd edition may never have materialized.

Second, we owe a big vote of thanks to our authors. Given the scale of the task

of coordinating the editing of 18 chapters from around the globe, Anne-Wil

would particularly like to acknowledge their wonderful responsiveness to the

repeated requests for text revision. Their cooperation in working within the

deadlines made the job so much easier. Anne-Wil’s research assistant, Sheila

Gowans, performed her job as proofreader with a perfect blend of commitment

and conscientiousness.

At Sage, Kiren Shoman was the first to believe in the book and convinced

the Sage board of the need for a 2nd edition. She was later joined by Keith Von

Tersch and together they made a perfect team. Seth Edwards then ensured that

the book moved through the production process smoothly, while Ben

Sherwood took care of the all important promotion of the book.

Anne-Wil Harzing

Joris Van Ruysseveldt

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page vii

Foreword by Nancy J. Adler

1

Which is farther, the sun at sunrise or the sun at noon? The first sage argued,

‘At sunrise, of course, the sun is closest when it is largest.’ The second sage

vehemently disagreed, ‘No, at noon, of course! The sun is closest when it’s

warmest.’ Unable to resolve the dilemma, the two sages turned to

Confucius.com for help. Feeling the sun’s fading warmth as it lowered itself

into a blazing sunset, Confucius remained silent.

2

Myth, misinformation, and silence have pervaded the field of international

human resource management (HRM) since its inception.

3

Understanding the

dynamics of people in organizations has always been challenging. However,

never prior to the twenty-first century has the intensity of globalization inter-

acted so profoundly with organizations and the people who lead them and

work in them. To understand the challenges of twenty-first century organi-

zational efficacy is to address the myriad of dilemmas facing people who con-

stantly work outside their native country with people from wider and wider

ranges of the world’s cultures.

Can we allow ourselves to continue to be guided by myth, misinformation,

and silence? No. Do we, as scholars, researchers, and executives, know how to

resolve the human dilemmas posed by extremely high levels of global inter-

action? No, not yet. Do we need to know? Yes. In International Human Resource

Management, the editors have brought together an eminent group of scholars

from around the world to report on state-of-the-art international HRM

research. Unlike Confucius, they have chosen not to remain silent in the face

of dilemmas that were heretofore unresolvable. They offer research results and

recommendations that can and should guide our scholarly and executive

appreciation of global diversity and its impact on human system functioning.

The book includes macro strategic perspectives along with micro individual-level

1

Nancy J. Adler is a professor of international management at McGill University, Montreal,

Canada.

2

Based on an ancient Chinese wisdom story as edited by Nancy J. Adler and Lew Yung-Chien

while artists in residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts, 2002.

3

For an in-depth discussion of the patterns of myths and errors undermining the field, see

A.W.K. Harzing’s ‘The Role of Culture in Entry Mode Studies: From Negligence to Myopia?’ in

Advances in International Management, Vol. 15, 2003, pp. 75–127; A.W.K. Harzing’s ‘Are Our

Referencing Errors Undermining our Scholarship and Credibility? The Case of Expatriate

Failure Rates,’ Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, February, 2002, pp. 127–148; and

A.W.K Harzing’s ‘The Persistent Myth of High Expatriate Failure Rates,’ The International

Journal of Human Resource Management, May 1995, pp. 457–475.

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page viii

perspectives. It encompasses perspectives from Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

It takes in the point-of-view of management and labour. Whereas neither this

book nor any book can answer all our questions about people working globally,

International Human Resource Management goes a long way in separating myth

and misinformation from research-based fact. It fills some of the field’s silence

with perceptive dialogue. It is a book well worth reading.

Foreword

ix

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page ix

Contributor Biographies

Chris Brewster

Professor of International Human Resource Management at Henley

Management College, UK. He had substantial experience in trade unions,

Government, specialist journals, personnel management in construction and

air transport, and consultancy, before becoming an academic. Chris has con-

sulted and taught on management programmes throughout the world and is a

frequent international conference speaker. He has conducted extensive

research in the field of international and comparative HRM; written some

dozen books and over a hundred articles. In 2002 Chris Brewster was awarded

the Georges Petitpas Memorial Award by the practitioner body, the World

Federation of Personnel Management Associations, in recognition of his out-

standing contribution to international human resource management.

Paula Caligiuri

Director of the Center for Human Resource Strategy and an Associate Professor

of Human Resource Management at Rutgers University in the United States.

She researches, publishes, and consults in the area of international human

resource management – specifically on the topics of expatriate management,

women on global assignments, and global leadership. Her research on these top-

ics has appeared in numerous journals and edited books. Dr Caligiuri is on the

editorial boards of Career Development International, Journal of Organizational

Behavior, Human Resources Planning Journal, and International Journal of Human

Resource Management and is an Associate Editor for Human Resource Management

Journal.

Christine Communal

Lecturer in International Management, Cranfield University, School of

Management, UK. Christine has the ability to enthuse people with her passion

for supporting individuals and organizations in the process of international-

ization. She has developed a unique approach to personal, managerial and

organizational development, with a strong focus on intercultural awareness.

Her early work experience was in France and Germany and encompassed vari-

ous industry sectors (petro-chemicals, mobile telephony and electricity distrib-

ution). She then moved to the UK to complete a Doctorate examining the

impact of national culture on managerial behaviour. Christine built on her

doctoral specialization to become the youngest Faculty member at Cranfield

School of Management, teaching on the MBA, Doctorate and Executive

programmes.

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page x

Tony Edwards

Lecturer in Comparative Management at King’s College, London. His research is

in the area of employment relations in MNCs. One of the themes of this research

is the diffusion of employment practices across borders within MNCs, with a spe-

cific focus on the process of ‘reverse diffusion’ in which practices are diffused from

foreign subsidiaries back to the domestic operations of MNCs. Currently he is

working on two projects, one of which is concerned with the ‘country of origin’

effect in American MNCs in the UK, while the other is concerned with the man-

agement of employment relations following a cross-border merger or acquisition.

Paul Evans

The Shell Chaired Professor of Human Resources and Organizational

Development and Professor of Organizational Behaviour at INSEAD, where he

has led INSEAD’s activities in the field of human resource and organizational

management since the early 1980s. He is co-author of Must Success Cost So

Much?, a pioneering study on the professional and private lives of executives;

Human Resource Management in International Firms: Change, Globalization,

Innovation, and The Global Challenge: Frameworks for International Human

Resource Management. He has a degree in law from Cambridge University, an

INSEAD MBA, a Danish business diploma, and his PhD is from MIT.

Marilyn Fenwick

Senior Lecturer in the Department of Management at Monash University. She was

awarded her PhD on expatriate performance management by the University of

Melbourne. She has published journal articles and book chapters in the areas of

international human resource management and international management.

Marilyn convenes a special interest group in International HRM for the Australian

Human Resources Institute in Victoria. Her research interests concern: non-

standard and virtual international assignments; human resources development

and performance management in multinationals; strategic HRM in international

inter-organizational networks and international non-profit organizations.

Hilary Harris

Director of the Centre for Research into the Management of Expatriation

(CREME) at Cranfield School of Management. Dr Harris has had extensive

experience as an HR practitioner and has undertaken consultancy with a broad

range of organizations in the public and private sectors. Her specialist areas of

interest are International HRM, expatriate management, cross-cultural man-

agement and women in management. She teaches, consults and writes exten-

sively in these areas. Hilary was one of the lead researchers on the CIPD

flagship research programme looking at the impact of globalization on the role

of the HR professional.

Anne-Wil Harzing

Associate Professor in the Department of Management at the University of

Melbourne. Her work on HQ-subsidiary relationships, staffing policies and

Contributor Biographies

xi

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xi

international management has been published in journals such as Journal of

International Business Studies, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of Organi-

zational Behavior and Organization Studies. She also published Managing the

Multinationals (Edward Elgar, 1999). Her current research interests include the

role of language in international business, the transfer of HRM practices across

borders, the interaction between language and culture in international

research, expatriates and knowledge transfer, and HQ-subsidiary relationships.

Richard Hyman

Professor of Industrial Relations at the London School of Economics and

Political Science (LSE) and is founding editor of the European Journal of

Industrial Relations. He has written extensively on the themes of industrial rela-

tions, collective bargaining, trade unionism, industrial conflict and labour mar-

ket policy, and is author of a dozen books as well as numerous journal articles

and book chapters. His most recent book, Understanding European Trade

Unionism: Between Market, Class and Society, was published by Sage in 2001 and

is already widely cited by scholars working in this field.

Terence Jackson

Holds a bachelors degree in Social Anthropology, a masters in Education, and

a PhD in Management Psychology. He is Director of the Centre for Cross

Cultural Management Research at ESCP-EAP European School of Management

(Oxford-Paris-Berlin-Madrid). He edits, with Dr Zeynep Aycan, the International

Journal of Cross Cultural Management (Sage Publications) and has recently pub-

lished his sixth book International HRM: A Cross Cultural Approach. He has pub-

lished numerous articles on cross-cultural management ethics, management

learning and management in developing countries in such journals as Human

Resource Management, Human Relations, Journal of Management Studies, and Asian

Pacific Journal of Management. He is currently directing a major research project

on Management and Change in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Mila Lazarova

Recently joined the International Management Department of the Faculty of

Business Administration at Simon Fraser University in Canada. Mila’s primary

research interests are in the area of international human resource management

and, more specifically, management of global assignees. Her recent research has

been focused on issues related to retention upon repatriation and the changing

notions of international careers. She has also done research on other related

topics such as cross-cultural adjustment and the expatriate experience of

female assignees. Mila has published in the Journal of International Human

Resource Management and the Journal of World Business and her work has been

presented at conferences in North America and Europe.

Paul Marginson

Professor of Industrial Relations and Director of the Industrial Relations

Research Unit at Warwick Business School, University of Warwick. He has

Contributor Biographies

xii

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xii

researched and published extensively on the management of employment

relations in MNCs and on the Europeanization of industrial relations. Major recent

projects include studies of the agreements establishing, and the practice and

impact of, European Works Councils; the industrial relations implications of

Economic and Monetary Union; and European dimensions to sector and com-

pany collective bargaining. A book with Keith Sisson – European Integration and

Industrial Relations: Multi-level Governance in the Making – is due to be published

by Palgrave-Macmillan in 2004.

Mark E. Mendenhall

Holds the J. Burton Frierson Chair of Excellence in Business Leadership at the

University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He is past president of the International

Division of the Academy of Management, and has authored numerous journal arti-

cles in international human resource management. His most recent book is Developing

Global Business Leaders: Policies, Processes, and Innovations (Quorum Books).

Jaap Paauwe

(PhD, Erasmus University) is Professor of Business and Organization at the

Rotterdam School of Economics, Erasmus University Rotterdam. He has writ-

ten and co-authored eleven books on human resource management and pub-

lished numerous papers on HRM, industrial relations and organizational

change. Twice (1997 and 2001) he was in charge of the editing of a special issue

on HRM and Performance for the International Journal of HRM. He is research

fellow and coordinator for the research programme on ‘Organizing for

Performance’ of the Erasmus Research Institute for Management (ERIM). Fields

of interest include human resource management, industrial relations, organi-

zational change, new organizational forms and corporate strategy.

Vladimir Pucik

Professor of International Human Resources and Strategy at IMD, Lausanne,

Switzerland. Born in Prague, he received his PhD in business administration

from Columbia University in New York and previously taught at Cornell

University and the University of Michigan. He also spent three years as a visit-

ing scholar at Keio and Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. Dr Pucik teaches reg-

ularly on executive development programmes in Europe, the US and Asia, and

has consulted and conducted workshops for major corporations worldwide. His

major works include The Global Challenge: Frameworks for International HRM,

Accelerating International Growth and Globalizing Management: Creating and Leading

the Competitive Organization.

Laurence Romani

Research Associate at the Institute of International Business (IIB) of the

Stockholm School of Economics (Sweden). She studied social anthropology

and sociology at the Sorbonne in Paris. Her research interests are in the field of

cross-cultural management. She is currently preparing her dissertation, which

focuses on quantitative studies of culture and management. She addresses their

Contributor Biographies

xiii

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xiii

issues and limitations with the endeavour of improving the current theoretical

models. Her research is inspired by an interpretative approach.

Hugh Scullion

Professor of International HRM at Strathclyde University. He previously worked

at Nottingham and Warwick Business Schools. Hugh is a Visiting Professor at

the Business Schools of Toulouse and Grenoble and also at Limerick University.

He consults with leading international firms such as Rolls Royce and Bank of

Ireland. Hugh researches on international strategy and international HRM in

European multinationals and has developed a strong network of HR directors

in Europe. He has written several books and over fifty specialist articles in

International HRM. Hugh’s latest books are International HRM: A Critical Text

(Palgrave, 2004) and Global Staffing (Routledge, 2004).

Keith Sisson

Head of Strategy Development at the UK’s Advisory, Conciliation and

Arbitration Service and Emeritus Professor of Industrial Relations in the

Warwick Business School’s Industrial Relations Research Unit (IRRU), having

previously been its Director. In recent years, he has been extensively involved

in cross-national comparative research involving projects funded by the UK’s

Economic and Science Research Council and the European Foundation for the

Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, including those on the role

of direct participation in organizational change, the impact of EMU and the

handling of restructuring. A book with Paul Marginson summarising many of

the results of this work (European Integration and Industrial Relations: Multi-level

Governance in the Making) is due to be published by Palgrave in 2004.

Günter K. Stahl

Assistant Professor of Asian Business and Comparative Management at INSEAD.

Prior to joining INSEAD, he was Assistant Professor of Leadership and Human

Resource Management at the University of Bayreuth, Germany. He also held vis-

iting positions at the Fuqua School of Business and the Wharton School of the

University of Pennsylvania. Günter has (co-) authored several books as well as

numerous journal articles in the areas of leadership and leadership development,

cross-cultural management, and international human resource management. His

current research interests also include international careers, trust within and

between organizations, and the management of mergers and acquisitions.

Arndt Sorge

Professor of Organization Studies at the Faculty of Management and

Organization, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. He has mainly

worked in international comparisons of work, organization, human resources,

technical change and industrial relations. This has implied uninterrupted expa-

triation through a succession of positions at several universities and research

institutes in Germany, his native country, The Netherlands, Britain and France.

Next to writing more specialist publications, based on field research in three

Contributor Biographies

xiv

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xiv

different societal contexts, he has also edited standard Organization volumes

in the series of the International Encyclopedia of Management and Organization,

most recently Organization (London: Thomson Learning, 2002), and he was

formerly editor-in-chief of Organization Studies.

Ibraiz Tarique

PhD Candidate at the School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers

University, New Jersey, USA. His research interests include human resource

management issues in cross-border alliances and training and development

issues in transnational enterprises. His teaching interests include strategic

human resource management, international human resource management,

and developing human capital. His research has been presented at the Annual

Academy of Management Meetings and at the Society of Industrial and

Organizational Psychologist Conferences and has been published in the

International Journal of Human Resource Management.

Joris Van Ruysseveldt

Associate Professor at the Open University of The Netherlands. He studied

Sociology at The Catholic University of Leuven. His dissertation (2000) focused

on collective bargaining structures in Belgium and The Netherlands. As research

manager at the Higher Institute of Labour Studies (University of Leuven), he

conducted research on topics like quality of working life, European works

councils, organizational learning and teamwork. He presently develops courses

in the field of human resource management. He has published articles and

books on industrial relations in Europe, comparative employment relations,

quality of working life and sociology of work.

Malcolm Warner

Professor and Fellow, Wolfson College and Judge Institute of Management,

University of Cambridge. He is the Editor of the International Encyclopedia of Business

and Management (London: Thomson, 6 volumes, 1996; second edition, 8 volumes,

2002) and Co-Editor of the Asia-Pacific Business Review. Professor Warner has written

and edited over 25 books and over 200 articles on management. His most recent

book, Culture and Management in Asia, is published by Routledge Curzon, 2003.

Ying Zhu

Senior Lecturer in the Department of Management, the University of

Melbourne. He graduated from International Economics Department at Peking

University and worked as an economist in the Shenzhen Special Economic

Zone in China. He completed his PhD at The University of Melbourne in 1992.

He was invited to be a visiting scholar at International Labour Organization in

Geneva in 1997. His research interests are international human resource man-

agement, industrial development and employment relations in East Asia,

including China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam. He has published a num-

ber of books and journal articles covering Asian economies, labour, industry

and human resource management.

Contributor Biographies

xv

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xv

Abbreviations

APEC Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation

CCC Chinese Culture Connection

CCP Chinese Communist Party

CCT Cross-Cultural Training

CEE Central and Eastern Europe

CFL Chinese Federation of Labour (Taiwan)

COEs Collective-owned Enterprises

CSAs Country-specific Advantages

DPEs Domestic Private Enterprises

ECB European Central Bank

EEA European Economic Area

EEC European Economic Community

EMU Economic and Monetary Union

ETUC European Trade Union Confederation

EU European Union

EWC European Works Council

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FOEs Foreign-owned Enterprises

FSAs Firm-specific Advantages

HCN Host Country National

HQ Headquarters

HR Human Resources

HRD Human Resource Development

HRM Human Resource Management

IHRM International Human Resource Management

IR Industrial Relations

JVs Joint Ventures

KMT Kumintang (Nationalist Party in Taiwan)

LDCs Less Developed Countries

LEs Large-sized Enterprises

M&A Mergers and Acquisitions

MNCs Multinational Corporations

MOL Ministry of Labour (Japan)

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

OJT on the job training

PCN Parent Country National

PRC People’s Republic of China

QCC Quality Control Circles

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xvi

SHRM Strategic Human Resource Management

SIRHM Strategic International Human Resource Management

SMEs Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises

SOEs State-owned Enterprises

TCN Third Country National

TQM Total Quality Management

UNICE Union of Industrial and Employers’ Confederations of Europe

VFTU Vietnam Federation of Trade Unions

WTO World Trade Organization

Abbreviations

xvii

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xvii

3122-prelims.qxd 10/29/03 2:20 PM Page xviii

Introduction

WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT?

This book provides a comprehensive, research-based, integrated and international

perspective of the consequences of internationalization for the management of

people across borders. The book’s comprehensiveness is evidenced by its wide

coverage. Although we will pay due attention to expatriate management in this

book, we will also look at the role of HRM in internationalization, the link

between strategy, structure and HRM in multinational companies (MNCs) and

the role of HRM in mergers and acquisitions. In addition, a discussion of

comparative HRM, which focuses on the extent to which HRM differs between

countries and the underlying reasons for these differences, will form a major

part of this book. Finally, the book offers a detailed treatment of the collective

aspects of the employment relation by looking at industrial relations from an

international and comparative perspective.

A second distinctive feature of this book is its solid research base. All chapters

have been specifically commissioned for this book and all authors are experts

and active researchers in their respective fields. Rather than having a final

chapter with ‘recent developments and challenges in IHRM’, we have given all

authors the clear brief to supplement classic theories and models with cutting-

edge research and developments. The chapter on cross-cultural training for

instance includes a discussion on recent development in electronic CCT and in

many chapters over two thirds of the references are less than five years old.

Although the book consists of 18 chapters written by a total of 23 authors,

it has been very carefully edited to provide an integrated perspective. Even

though the book is research-based, it is not a disparate collection of research

essays. All chapters are part of a carefully constructed framework and together

provide a coherent picture of the field of International HRM.

A fourth and final distinctive characteristic of this book is that it is truly

international, both in its outlook and in its author base. Authors use examples

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 1

from all over the world and their research base extends beyond the traditional

American research literature. Although many authors are currently working at

American or British universities, virtually all have extensive international

experience and their countries of origin include: the Netherlands (2 authors),

France (2 authors), Germany (2 authors), Bulgaria, Slovakia, Pakistan, Australia

and China.

WHO IS THIS BOOK FOR?

As a textbook this book will appeal to advanced undergraduate students and

Master’s students wanting a comprehensive and integrated treatment of

International HRM that includes the most recent theoretical developments. As

a research book, it provides PhD students and other researchers with a very

good introduction to the field and an extensive list of references that will allow

them to get an up-to-date overview of the area. Finally, practitioners looking

for solutions to their international HR problems might find some useful frame-

works in Parts 1 and 3, while the chapters in Parts 2 and 4 will allow them to

get a better understanding of country differences in managing people.

WHAT IS NEW IN THE 2ND EDITION?

The underlying philosophy of this book – presenting a comprehensive,

research-based, integrated and international perspective on managing people

across borders – has not changed. However, the 2nd edition has reinforced

these four characteristics in the following ways:

• Since several reviewers commented that the comparative aspect of the

1st edition left room for improvement, Part 2 of the book has been

completely revised and the current edition includes three new chapters

on comparative HRM, covering Europe, Asia and developing countries.

Two new chapters on the role of HRM in mergers and acquisitions in

Part 1 and on repatriation in Part 3 reflect the increasing importance of

these phenomena. Part 4 features a new chapter on transfer of employ-

ment practices across borders, as well as a revised treatment of the most

important aspects of industrial relations.

• The research base has been further reinforced by attracting new authors

who are experts and active researchers in their field. This means that

International Human Resource Management

2

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 2

most chapters have been written from scratch, while the remaining

chapters (Chapters 1, 5 and 14) have been updated. In doing so, the

authors have focused even more strongly on theoretical models and

frameworks, cutting down on factual information that can easily be

retrieved from other sources, including other textbooks.

• The integrated perspective has been strengthened by even more careful

editing. Most authors went through three versions of their chapters and

many read chapters of other authors in order to avoid overlap and con-

flicting evidence. Links have been provided between chapters to further

clarify the overall structure of the book, and in order to help instructors,

discussion questions and suggestions for further reading are now pro-

vided with each chapter.

• The book has moved from a predominantly Dutch author base in the 1st

edition to a truly international group of authors, coming from or working

in more than ten different countries, in this edition. The book has main-

tained its distinctive European focus (especially in Part 4), but with new

chapters on Asia and developing countries and new authors from the

US, China and Australia, it has now reached out to other areas of the

world as well.

WHAT IS INCLUDED IN THIS BOOK?

This book consists of four clearly delineated parts. Each part can be studied as

an independent unit, so that readers may choose to study the parts most inter-

esting to them, if they so desire. Taken together, however, the four parts

present a consistent picture of the way in which international HRM can be

approached as a discipline.

In Part 1 (Internationalization: Context, Strategy, Structure and Processes)

we first place International HRM in a wider context. Chapter 1 touches upon

recent developments in the field of internationalization and offers various theo-

retical models which explain the existence of international trade and multi-

national companies. We also look at the social consequences of the increasing

internationalization of the global economy. Chapter 2 then discusses the

different options that MNCs have in terms of strategy and structure in some

detail and shows that these can be combined into a typology of MNCs that

stands up to empirical verification. We also provide a preview of the link between

strategy, structure and HRM, an issue that is further explored in Chapter 3. That

chapter also traces the development of IHRM as a research field and examines the

role of the corporate HR function in the international firm, global management

development and the roles and responsibilities of transnational managers.

Introduction

3

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 3

Finally, Chapter 4 focuses on integration processes in cross-border mergers and

acquisitions (M&A), examining the potentially critical role that cultural differences

and human resources play in the M&A process. It also systematically reviews the

key HRM challenges at different stages in the M&A process.

Part 2 (HRM from a Comparative Perspective) starts with two chapters

offering two different approaches – institutionalist and culturalist – to explain

differences in human resource management across borders. Chapter 5 intro-

duces these two approaches and explains the way in which comparative

research differs between them. The chapter then reviews the institutionalist

approach in some detail before proposing a framework – termed societal

analysis – to integrate the two approaches. Chapter 6 then focuses on the study

of cultural differences across countries that influence people in a work environ-

ment. It presents the achieved knowledge on cultural dimensions which helps

understanding and managing people from different cultural backgrounds and

reviews three major and distinctive contributions to this debate. Subsequently,

Chapters 7 to 9 discuss how HRM practices differ across countries by focusing

respectively on Europe, Asia and developing countries. All three chapters come

to the conclusion that there are no ‘one-size-fits-all best HRM practices’ and

that Anglo-American HRM models need to be adapted to be effective in other

countries. The focus in these chapters is on acquiring an analytical

understanding of cross-national differences, since any factual description of

such differences would soon be out of date.

In Part 3 (Managing an International Staff) we return to the perspective of

the MNC and discuss the issues that an international HR manager encounters

in managing people across borders. Although this part of the book has a clear

focus on the management of expatriates, many chapters explicitly broaden

their scope to include all managerial personnel. First, Chapter 10 discusses the

challenges associated with building an international workforce. It reviews

different staffing policies and the factors influencing the choice between host

country and parent country nationals as well as the underlying motives for

international transfers. It also covers recruitment and selection issues and

expatriate adjustment and failure. Chapter 11 looks at the preparation of expatriates

for their international assignments and proposes a systematic five-phase

process for designing effective cross-cultural training programmes. Chapter 12

then deals with the compensation and performance management of staff in

MNCs. It reviews the variables influencing international compensation strategy;

options for compensating staff on international transfer within MNCs; and

problems and enduring issues associated with international compensation and

integrated performance management. Chapter 13 then closes the international

transfer cycle with a look at the challenges associated with repatriation follow-

ing global assignments from both an individual and an organizational point of

view. Finally, Chapter 14 looks at the role of women in international manage-

ment, taking into account individual, organizational and socio-cultural

perspectives.

International Human Resource Management

4

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 4

The fourth and final part of this book (Industrial Relations: a Comparative

and International Perspective) looks at the collective aspects of the employ-

ment relationship. First, Chapter 15 links back to Chapters 2 and 3 by

discussing the transfer of HR practices – or more generally employment prac-

tices as they are called in this chapter – within MNCs. It provides explanations

for variations between MNCs in terms of the extent of transfer and a discussion

of the likely nature of the relations between different groups within MNCs in

the transfer process. Chapter 16 then draws on the recent literature on ‘varie-

ties of capitalism’ to show that national economies can be structured in many

different ways, and that these differences are associated with different indus-

trial relations systems. It also disentangles the challenges inherent in globali-

zation, and considers whether they imply convergence towards a more

market-driven model, or whether distinctive forms of social regulation are

likely to persist. In Chapter 17, we take this analysis of convergence and diver-

gence one step further by moving to the regional level of analysis and reflecting

about the prospects for the ‘Europeanization’ of industrial relations. In the

final chapter of this book – Chapter 18 – we take our analysis back to the

company level by examining the relevance of the concept of the Eurocompany

and the role of European Works Councils within European industrial relations.

Introduction

5

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 5

Introduction.qxd 10/29/03 2:33 PM Page 6

PART 1

Internationalization: Context, Strategy,

Structure and Processes

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 7

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 8

1 Internationalization and the International

Division of Labour

Anne-Wil Harzing

1 Introduction 9

2 Statistics on internationalization trends 10

3 Determinants of international trade 11

4 The reason for multinational companies 15

5 The comparative and competitive advantage of nations 19

6 Trends in the international division of labour 24

7 The competitive advantage of multinational companies 28

8 Summary and conclusions 30

9 Discussion questions 30

10 Further reading 31

References 31

1 INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, which will set the background for the remainder of this book,

we will discuss a number of important issues with regard to internationali-

zation and the international division of labour. We will begin in Section 2 by

offering some statistical data which demonstrate the importance not only of

international trade but also of foreign direct investment (FDI). Sections 3 and

4 will next discuss a number of theories which explain these phenomena. In

Section 5, we will explore product specialization across countries. We will do

this using Porter's analysis, which explains the competitive advantage of

CHAPTER CONTENTS

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 9

nations. We will then go one step further to the global level, when, in Section 6,

we will look at the (new) international division of labour and the economic

and social consequences thereof. Finally, in the last section we will discuss the

sources of competitive advantage for multinationals.

2 STATISTICS ON INTERNATIONALIZATION TRENDS

International trade

The year 2001 saw the first decline in the volume of world trade since 1982,

mostly due to a decline of economic activity in the three major developed

markets (the USA, Japan and the European Union), the bursting of the global

IT bubble and the aftermath of the tragic events of September 11 (WTO, 2002).

However as Figure 1.1 indicates, historical data show that international trade

has become much more important in the last 50 years. The growth in inter-

national trade has consistently surpassed the growth in production. While the

world production in 2001 is seven times as high as in 1950, international trade

is more than 20 times as high.

It is important to note, however, that a lot of international trade could

more properly be called regional trade, covered by major regional trade agree-

ments such as NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), the EU

(European Union) and APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation): 43% of the

exports within NAFTA, 65% of the exports within the EU and 68% of the

exports within APEC do not leave the region (WTO, 2002). In Section 3 we will

discuss a number of theories which explain the existence of international

trade.

Foreign direct investment

Foreign investments of multinational firms are even more important than

international trade for the growth of the world economy. In 2001 the sales of

foreign subsidiaries of multinational companies (MNCs) were nearly twice as

high as world exports, while in 1990 the two were roughly equal. Although,

just like international trade flows, FDI flows have suffered a substantial decline

in 2001, the longer term prospects remain promising, with major MNCs likely

to continue their international expansion (UNCTAD, 2002). The influence of

MNCs is reflected in the increase in the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI)

and the growth in the number of multinationals and their foreign subsidiaries.

As shown in Table 1.1, the total stock of foreign investment has reached almost

$7 trillion. More than 850,000 foreign subsidiaries of about 65,000 parent firms

International Human Resource Management

10

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 10

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1950–63 1963–73 1973–90 1990–01

Trade

Production

contributed approximately $18.5 trillion to world sales in 2001, while the

number of employees in foreign affiliates has more than doubled in the last

decade. In Section 4 we will discuss a number of theories which explain the

existence of foreign direct investment.

3 DETERMINANTS OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE

In this section we will briefly consider a number of theories which explain why

countries trade with one another. We will therefore be emphasizing the coun-

try level. In the following section we will shift our discussion to theories focus-

ing on the multinational organization. These theories explain why

multinationals exist.

First, we will consider two ‘classic’ theories of trade, which are based on the

idea that country-specific factors (also known as location-specific factors) are

decisive for international trade. Such country-specific factors may offer

absolute or relative comparative cost advantages. A third theory explains why

international trade may arise even in the absence of such cost advantages. The

key term here is economies of scale. Later, in Section 5, we will explore Porter's

analysis, the latest in a long line of international trade theories reaching back

more than two centuries.

The International Division of Labour

11

FIGURE 1.1

Growth of world production and world trade (% change in volume terms) (WTO, 2002)

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 11

TABLE 1.1

Absolute and relative comparative cost advantages

This theory takes us back to the founding father of modern economics: Adam

Smith. In his book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

(1776), Smith explains that the division of labour can lead to increased pro-

ductivity, because each person does what he or she is best at or can produce

most efficiently. This applies at every level, for example within families or

within a country as a whole. An efficient division of labour between countries

is present whenever location-specific advantages, such as the presence of

certain natural resources, make it possible for one country to produce a certain

product more cheaply than another.

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to

attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than

to buy. The tailor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but

buys them from the shoemaker…What is prudence in the conduct

of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great king-

dom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity

cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with

some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way

in which we have some advantage. (Adam Smith, 1776: 424–425)

There was one problem with this theory, however. What if a country has no

location-specific advantages and therefore no cost advantages? Will it still be

in a position to trade with other countries? And even if it is, would it not end

up importing far more than it exports, so that an ever increasing amount of

money would leave the country?

International Human Resource Management

12

Selected indicators of FDI and international production, 1982–2001

Value at current prices

(billions of dollars) Annual growth rate (%)

1986– 1991– 1996–

1982 1990 2001 1990 1995 2000

FDI inward stock 734 1874 6846 15.6 9.1 17.9

FDI outward stock 552 1721 6582 19.8 10.4 17.8

Sales of foreign affiliates 2541 5479 18517 16.9 10.5 14.5

Employment of foreign

affiliates (thousands) 17987 23858 53581 6.8 5.1 11.7

Source: adapted from UNCTAD, 2002

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 12

David Ricardo (1772–1823) showed that even if a country had no absolute

cost advantages, it would still be able to grow more wealthy through interna-

tional trade. We can demonstrate this by using a simple model involving two

countries (A and B) and two commodities (x and y). Country A produces both

Commodity x and Commodity y against the lowest possible costs.

Country A Country B

Commodity x costs 5 12.5

Commodity y costs 20 25

The difference between Country A and Country B is larger for Commodity x,

however, than it is for Commodity y. If we consider the terms of exchange (the

number of units of Commodity x exchanged for one unit of Commodity y and

vice versa), we can construct the following table.

Country A Country B

1x =

1

4

y 1x =

1

2

y

1y = 4x 1y = 2x

We see that the inhabitants of Country A can profit by buying Commodity y

in Country B. In Country B they only have to pay 2x, while in their own country

they have to pay 4x. Inhabitants of Country B would do well to buy their

Commodity x in Country A. In doing so they only have to pay

1

4

y, while in

their own country it would cost them

1

2

y. We can say that Country A has a rel-

ative comparative cost advantage in producing Commodity x, while Country

B has a relative comparative cost advantage in producing Commodity y.

Inhabitants of Country A will therefore try to exchange their Commodity x for

the Commodity y of Country B. The inhabitants of Country B would be very

willing to do so because this exchange is also to their benefit. This is how inter-

national trade was born. To comply with the extra foreign demand, Country A

would have to specialize in producing Commodity x and Country B in pro-

ducing Commodity y. According to Smith and Ricardo, international trade

arose because of the existence of comparative cost advantages, whether

absolute or relative.

The Heckscher–Ohlin theorem

This brings us to the question: where do such cost differences come from? One

answer, known as the Heckscher–Ohlin (H–O) theorem, was introduced by the

Swedish economists Heckscher and Ohlin. Comparative cost differences are the

result of differences in factor endowments (labour, land and capital). Some coun-

tries, for example, have a relatively large quantity of capital and relatively small

The International Division of Labour

13

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 13

labour force (for example, Western nations). Other countries have relatively little

capital and a large labour force (for example, most of the developing nations).

Note that it is the relative position of these production factors with respect to one

another that counts. We would not, for example, say that Zaire has more labour

than the US (which is untrue) or that it has more labour than capital (how would

one go about measuring that?). We can, however, say that Zaire has more labour

available per quantity of capital than the United States does.

Production factors available in relatively large quantities will be inexpen-

sive, and vice versa. (For the time being we will not consider the demand con-

ditions. A country may, for example, have absolutely no demand for a domestic

good produced with scarce production factors, resulting in a low price.) In a

country that possesses a relatively large amount of capital and very little labour,

capital-intensive products will be cheap and labour-intensive products expen-

sive. The reverse will be true for a country with a relatively small amount of

capital and a large labour force. The same arguments can be offered for the

production factor ‘land’. The impact on international trade is that

commodities requiring for their production much of [abundant

factors of production] and little of [scarce factors] are exported in

exchange for goods that call for factors in the opposite propor-

tions. Thus indirectly, factors in abundant supply are exported

and factors in scant supply are imported. (Ohlin, 1933: 92)

In global terms, we can explain international trade flows rather well using this

theorem. Japan, a country with a relatively limited amount of land, imports

many of its primary products. Third World countries with a relatively large

body of (unskilled) labour export labour-intensive products such as textiles and

shoes.

There are, however, two postwar trends that have presented a considerable

challenge to the H–O theorem. Firstly, there is the fact that a large and increas-

ing share of international trade takes place between countries with similarly

large incomes. Secondly, a large and increasing share of international trade

consists of two-way trade involving similar manufactured products (known as

intra-industry trade). As a result, new theories of trade have been introduced

which reject country-specific factors to a certain extent and which turn instead

to sector- or company-specific factors that might lead to a strong competitive

position. The key term in such new theories is ‘economies of scale’.

Economies of scale

We have not yet mentioned an important assumption underlying the classic

trade theories: yield remains constant regardless of the scale of production.

In other words, the average cost per product will remain the same. In actual

practice, however, we see economies of scale in many branches of industry – as

International Human Resource Management

14

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 14

the scale of production increases, the average cost per product decreases. These

economies of scale might appear in production, in R&D, in purchasing, in

marketing or in distribution. A very simple case of economies of scale are the dis-

counts offered on quantity purchases (which are in turn based on the supplier’s

economies of scale). Economies of scale in production may be the result of a

division of labour and specialization or of cost-cutting measures (for example,

robots in auto manufacturing) which only become profitable at a certain

minimum production level. After all, it would hardly pay to set up a robot

assembly line if you are only going to produce three cars.

In addition to these economies of scale, which are known as internal

economies of scale (in other words, within one company), there are also external

economies of scale. These are closely related to the size of an industry and not to

the size of the individual company. A concentration of companies in a particular

region, for example semiconductor manufacturers in Silicon Valley in California,

may give rise to a good infrastructure, a specialist labour force and a network of

suppliers (see also Porter’s analysis in Section 5). This means that individual com-

panies within this industry can achieve economies of scale, despite the fact that

large companies produce no more efficiently in the sector than small companies.

How do such economies of scale affect international trade? We noted previ-

ously that international trade depends on absolute or relative comparative cost

advantages, which are the result of differences in factor endowments. According

to the classic theories of trade, countries with comparable factor proportions will

not trade with one another because they will not be able to gain absolute or

relative comparative cost advantages. However, when economies of scale are

applied, a system in which one country produces one product and a second

country produces another can nevertheless offer advantages. Because production

can take place on a larger scale, the average costs of both products will drop. Both

countries can therefore gain through specialization and international trade.

How can we predict which country will produce which product if neither

country can gain a cost advantage? The answer is: we can’t. It is frequently a

combination of serendipitous factors which leads to a certain industry setting

up first in a certain country. Through internal and/or external economies of

scale, this country will be able to build up such an advantage that it becomes

very difficult for anyone else to catch up.

4 THE REASON FOR MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES

The theories discussed in the previous section explain how international trade –

the conveying of goods across borders – arises and what constitutes it. A second

assumption – the first being constant returns to scale (see Section 3) – which

the classic theories make, is that the production factors present in a particular

The International Division of Labour

15

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 15

country will move about within the country itself, but not across the national

borders. According to the H–O theorem, international trade will gradually

eliminate differences between production factor rewards in the various coun-

tries. In this way, exporting labour-intensive goods to a country with a rela-

tively small labour force may have the same effect as actually relocating labour

as a production factor to this country.

In reality, however, production factors do move across borders. Cash capital

and to a lesser extent labour are becoming increasingly mobile. A large proportion

of the international flow of cash is motivated by a desire to simply invest money

to get a return on investment, just as one would do by putting money in a sav-

ings account. British investors, for example, may purchase shares on the stock

market in a Japanese company in order to gain an income from their investment

(dividends and/or gains made by stock fluctuations), either in the short term or in

the long term. However, a portion of this cash flow consists of Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI). These are investments made in foreign countries with the

explicit goal of maintaining control over the investment. By making use of FDI, a

company may, for example, be able to set up production facilities in a foreign

country, thereby joining the ranks of multinational companies.

The question, however, is why a company would choose direct investment

when it can simply export the goods produced in its own country and import

the raw materials or semi-manufactures required, or even license the relevant

know-how. Initially the answer to this question consisted of partial explana-

tions. Firstly, companies in highly protectionist countries made use of direct

investment to get around import restrictions and tariff walls. Secondly, FDI

made it possible for companies whose production relied heavily on certain raw

materials to secure the supply of such materials. A third explanation was that

the high cost of transport made exporting more expensive than establishing

foreign production facilities. Sometimes FDI can also be viewed as a strategic

market tactic. For example, American companies may invest in the Japanese

market simply to make life so difficult there for Japanese firms that they in turn

no longer have the resources left to enter the American market. None of these

arguments, however, offered a systematic explanation for the rise of the multi-

national in general. In the following sections we will discuss two theories that

do offer such an explanation: Vernon’s product life cycle theory and Dunning’s

eclectic theory of direct investment.

Product life cycle

Vernon’s product life cycle (PLC) theory (Vernon, 1995) takes its name from

the product life cycle familiar to students of marketing theory. In the first

phase, the introductory or start-up phase, the new product is introduced. It is

innovative, it has not yet been standardized and it is relatively expensive.

Because the product will evolve further throughout this phase, the producer

and the consumer must be in direct contact. Production and sales can only take

International Human Resource Management

16

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 16

place in the country where the product is being developed, for example in the

United States (in principle the PLC theory pertains to high-tech products

which, at the time this theory was introduced – the 1950s – came largely from

the US). In the expansion phase, the product becomes more standardized and

the price falls a bit. Turnover increases sharply and production costs begin to

drop. To extend this phase, a company will attempt to export its product.

Because the price is still rather steep, exports will largely go to countries which

have a similar income level, for example Europe.

At the end of the expansion phase and the beginning of the maturity

phase, the company will begin to manufacture the product in Europe.

Turnover there will have increased to such an extent that it pays to set up

foreign production, particularly in view of import tariffs and transport costs. By

this time however, the product will have become so standardized that

European companies will be jumping on the bandwagon. By setting up its own

subsidiaries in Europe then, the American company is applying a defensive

strategy designed to protect its market position.

In the end the production process will be completely standardized, making

economies of scale and mass production possible. The quality (level of skill) of

the workforce in the production process becomes less important than how

much it costs. Production will therefore increasingly take place in labour-

abundant countries. This refers to elements of the classic theories of trade.

The product life cycle model made an important contribution to explain-

ing the enormous scope of direct investment by American companies in the

1950s and 1960s (see Chapter 2). However, the model fails to answer two

important questions. Firstly, why does one company in a country become a

multinational while another does not? Secondly, why would a company

choose to maintain control of the production process by setting up sub-

sidiaries? It would be much simpler to license the know-how required to man-

ufacture the product to a foreign company. Both of these questions are

answered by Dunning’s eclectic theory, which also incorporates the location-

specific advantages proposed in the classic theories of trade.

Dunning’s eclectic theory

Dunning’s eclectic theory (Dunning & McQueen, 1982), also called the trans-

action cost theory of international production, is able to explain why firms pro-

duce abroad, how they are able to compete successfully with domestic firms and

where they are going to produce. In doing so, the theory selectively combines

elements of various other theories (hence the name ‘eclectic’). According to

Dunning, a company that wishes to set up production in a foreign country and

operate as a multinational must simultaneously meet three conditions: it must

have ownership advantages, location advantages and internalization advantages.

Ownership advantages, also known as firm-specific advantages, are specific

advantages in the production of a good or service which are unique to a particular

The International Division of Labour

17

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 17

company. The range of advantages, which can be both tangible and intangible, can

be very wide. According to Rugman (1987) they can be summarized as follows:

• proprietary technology due to research and development activities;

• managerial, marketing, or other skills specific to the organizational function of

the firm;

• product differentiation, trademarks, or brand names;

• large size, reflecting scale economies;

• large capital requirements for plants of the minimum efficient size.

The presence of ownership advantages, however, in no way fully explains the

existence of the multinational company. For example, if a company gains an

ownership advantage over other companies for a certain foreign market, it

could simply export its products to that market. That is why the second con-

dition must also be present: location advantages.

Location advantages include all of the factors which we discussed with

respect to the classic theories of trade and which we will discuss in Section 5

with respect to Porter’s analysis, ranging from an abundance of fertile land and

cheap labour to a liberal capital market and a sound infrastructure. To that we

can also add the favourable investment conditions offered by some countries in

order to attract foreign investors. These may be in the form of subsidies, tax

exemptions, or cheap housing. The benefits for the firm come from the combi-

nation of ownership advantages and location advantages. However, even if this

is the case, it will not necessarily lead to FDI and, therefore, to the establishment

of a multinational company. After all, the company can also sell its ownership

advantages or license them out to another company in the foreign market. That

is why the third condition must be met: internalization advantages.

A company possesses internalization advantages if it is more profitable to

exploit its ownership advantages itself in another country than to sell or

license them. There are countless arguments in favour of internalization. To a

large extent these arguments have their origin in Coase’s and Williamson’s

transaction cost approach (1937 and 1975 respectively). In the first place, if the

ownership advantage is a combination of highly specific company factors, it

might be difficult to sell or license it. And even if it were possible, the advan-

tages and the contract for these advantages would be so complex that setting

up and exploiting them would be extremely costly. This applies to a lesser

degree if the advantage being sold is a specific, easily isolated invention. The

problem in this situation, however, is that it would be difficult for the

buyer/licensee to get a good idea of what he is purchasing or acquiring a licence

for. After all, if the licensor releases too much information before concluding

the contract, he will have very little left to sell or license. Finally, the company

may be afraid that by licensing certain company-specific knowledge, this

International Human Resource Management

18

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 18

knowledge will either leak out, making further licences difficult, or be used in

such a way that it damages the good name of the licensor. In each case there

are internalization advantages, so that a company will decide to carry out the

relevant activity itself in the foreign country.

Like rival theories, Dunning's approach is not seen as the be-all and end-

all explanation for the existence of multinationals. It does, however, succeed in

bringing together, in an elegant manner, what were until then a number of

relatively separate schools of thought.

By now we have discussed a number of reasons for international trade and

FDI. However, we cannot as yet explain why a particular nation is able to

achieve international success in a particular industry. In other words: why are

certain products successful in one country while other products are produced

in another country?

As we mentioned earlier, the theory of absolute and relative comparative

cost advantages (Section 3) offers a reasonable explanation for general trends

in international trade flows. Usually, however, these advantages cannot explain

why a certain country imports or exports specific industrial goods. As we will

discover in Section 7, economies of scale (Section 3) are an important source of

competitive advantage in many sectors of industry. We have already seen, how-

ever, that this theory does not really answer the question as to which country

will produce which product. The product life cycle theory (Section 4) has cer-

tainly made an important contribution to explaining the distribution of some

high-tech products, but it raises almost as many questions as it answers. Why

is it that one particular country leads the rest in a new industry? Why are some

industries seemingly immune to the loss of competitive advantage suggested

by Vernon? And why is it that in many sectors of industry, innovation is now

seen as an on-going process and not a one-off event, after which an invention

quickly becomes standardized and production is taken over by low-wage coun-

tries? Finally, Dunning’s eclectic theory (Section 4) provides us with a very

interesting and more or less comprehensive explanation of the existence of

multinational companies. It does not, however, explain why some countries

gain particular ownership advantages while others do not.

5 THE COMPARATIVE AND COMPETITIVE

ADVANTAGE OF NATIONS

Criteria for a theory of national comparative

and competitive advantage

In this section we will discuss Porter's analysis, in which he attempts to

provide an explicit answer to the questions listed above. Porter maintains that

The International Division of Labour

19

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 19

a theory of national comparative and competitive advantage must meet the

following criteria:

• It must explain why firms from some nations choose better strategies than those

from other nations for competing in particular industries.

• It must explain why a nation is home base for successful global competitors in

a particular industry that engages in both trade and FDI.

• It must explain why a firm in a particular nation realizes competitive advantage

in all its forms, not only the limited types of factor-based advantage included in

the traditional theory of comparative advantage as discussed above.

• It must recognize that competition is dynamic and evolving, rather than taking

a static view focusing on cost efficiency due to factor or scale advantages.

Technological change should be seen as an integral part of the theory.

• It must allow a central place for improvement and innovation in methods and

technology and should be able to explain the role of the nation in the innova-

tion process. Why do some nations invest more in research, physical capital,

and human resources than others?

• It must make the behaviour of firms an integral part of the theory as

traditional trade theory is too general to be of much relevance for

managers. (Porter, 1990: 19–21)

Porter naturally attempts to satisfy these conditions in his own analysis. After

conducting a four-year study involving ten countries (Denmark, Germany,

Italy, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US), he was

convinced that national competitive advantage depends on four determinants,

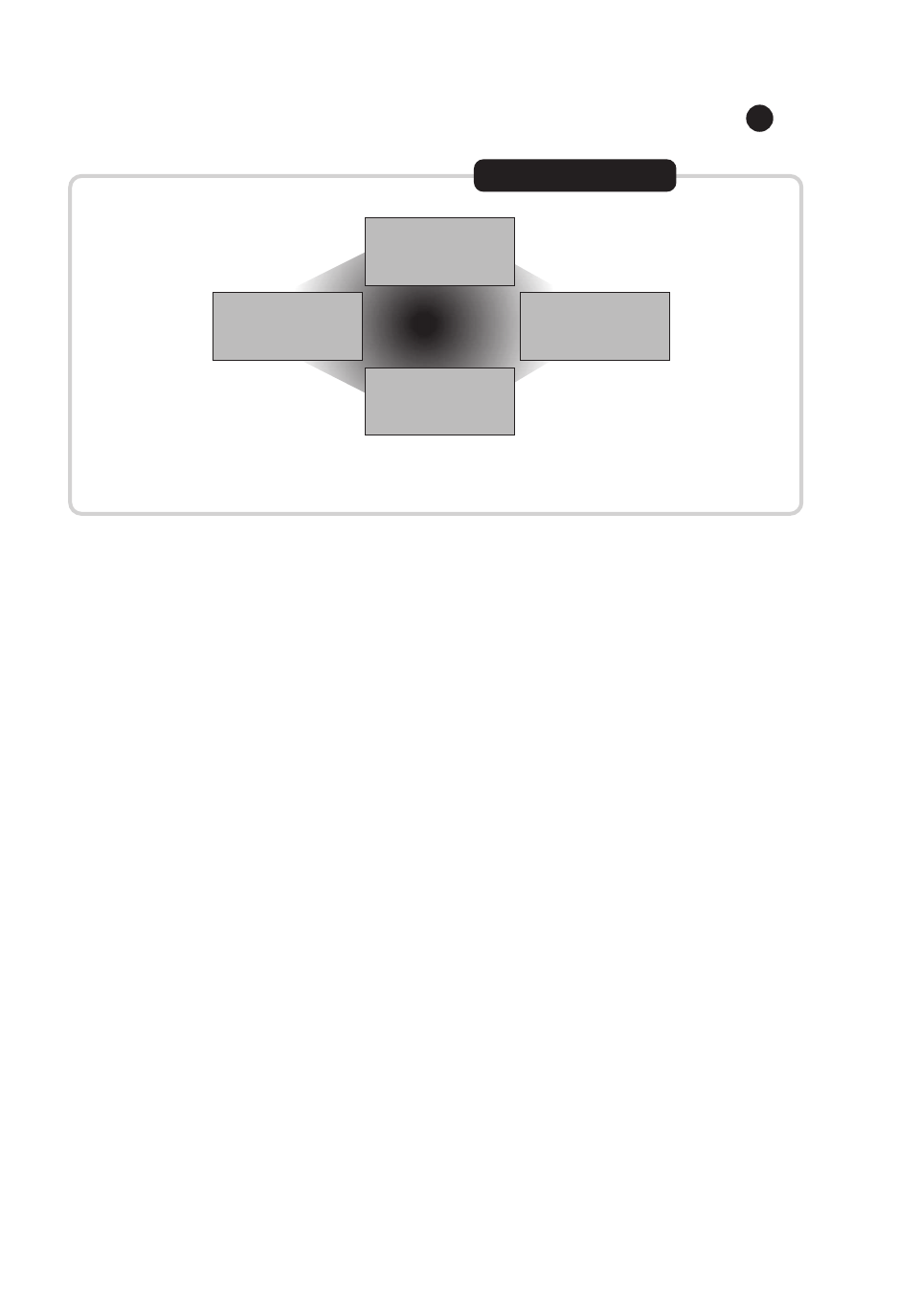

represented as a diamond (Porter's diamond, see Figure 1.2). (The complete

model also includes the factors government and chance, which make their

influence felt through the four determinants.)

The four determinants of national comparative

and competitive advantage

We will discuss these four determinants below, paying particular attention to

factor conditions and to firm strategy and structure, which have the greatest

bearing on this book.

Factor conditions

The first determinant, factor conditions, shows traces of the classic inter-

national trade theories proposed by Smith, Ricardo and Heckscher/Ohlin.

However, whereas these theories concentrated on the traditional production

International Human Resource Management

20

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 20

factors such as land and, specifically, labour and capital, Porter goes much

further. He agrees with them with respect to labour (which he calls human

resources), land (physical resources) and capital (capital resources), but in his

view these categories are much broader than the classic theories would suggest.

For example, while Ricardo principally saw labour as a large, undefined mass of

cheap workers, Porter emphasizes quality as well as quantity and divides human

resources ‘into a myriad of categories, such as toolmakers, electrical engineers

with PhDs, applications programmers, and so on’. Physical resources also cover

the location of a country with respect to its customers and suppliers, while

capital resources can be divided into ‘unsecured debt, secured debt, “junk”

bonds, equity and venture capital’. In addition to these ‘traditional’ production

factors, Porter also identifies knowledge resources and infrastructure as factors

which can be decisive for the competitive advantage of a country. He sees

knowledge resources as ‘the nation’s stock of scientific, technical and market

knowledge bearing on goods and services’, while infrastructure includes trans-

port and communications systems, the housing stock and cultural institutions.

The differences described in Parts 2 and 4 of this book with respect to education,

training, skills, industrial relations and motivation can all be seen as factor con-

ditions which influence a country’s competitive advantage.

Demand conditions

The second determinant consists of demand conditions. Traditional trade

theories tended to neglect the demand side. According to Porter, demand in

the home market can be highly important for a country’s national competitive

The International Division of Labour

21

Related and

supporting

industries

Firm strategy,

structure, and

rivalry

Factor

endowments

Demand

conditions

Porter’s diamond (adapted from Porter, 1990)

FIGURE 1.2

3122 Ch-01.qxd 10/29/03 4:09 PM Page 21

advantage. In addition to the size of the demand (which can lead to economies