HIGHER EDUCATION

State Funding Trends

and Policies on

Affordability

Report to the Chairman, Committee on

Health, Education, Labor, and

Pensions, United States Senate

December 2014

GAO-15-151

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-15-151, a report to the

Chairman, Committee on Health, Education,

Labor, and Pensions, United States Senate

December 2014

HIGHER EDUCATION

State Funding Trends and Policies on Affordability

Why GAO Did This Study

There is widespread concern that the

rising costs of higher education are

making college unaffordable for many

students and their families. Federal

and state support is central to

promoting college affordability;

however, persistent state budget

constraints have limited funding for

public colleges. GAO was asked to

study state policies affecting

affordability and identify approaches to

encourage states to make college

more affordable.

This report examines, among other

things, how state financial support and

tuition have changed at public colleges

over the past decade. It also examines

how the federal government works with

states to improve college affordability

and what additional approaches are

available for doing so. In conducting

this work, GAO analyzed trends in

state funding for public colleges,

tuition, and state student aid using data

from the U.S. Department of Education

for all public sector colleges from fiscal

years 2003 through 2012, the most

recent data available at the time of this

study. GAO also identified academic

studies on state higher education

policies and affordability published

since 2011 and interviewed 25

academic experts and organizations in

the fields of higher education or state

policy. Finally, GAO reviewed

Education programs and proposals

and obtained perspectives from

experts and organizations to identify

approaches the federal government

could use to incentivize state action.

What GAO Recommends

GAO does not make recommendations

in this report.

What GAO Found

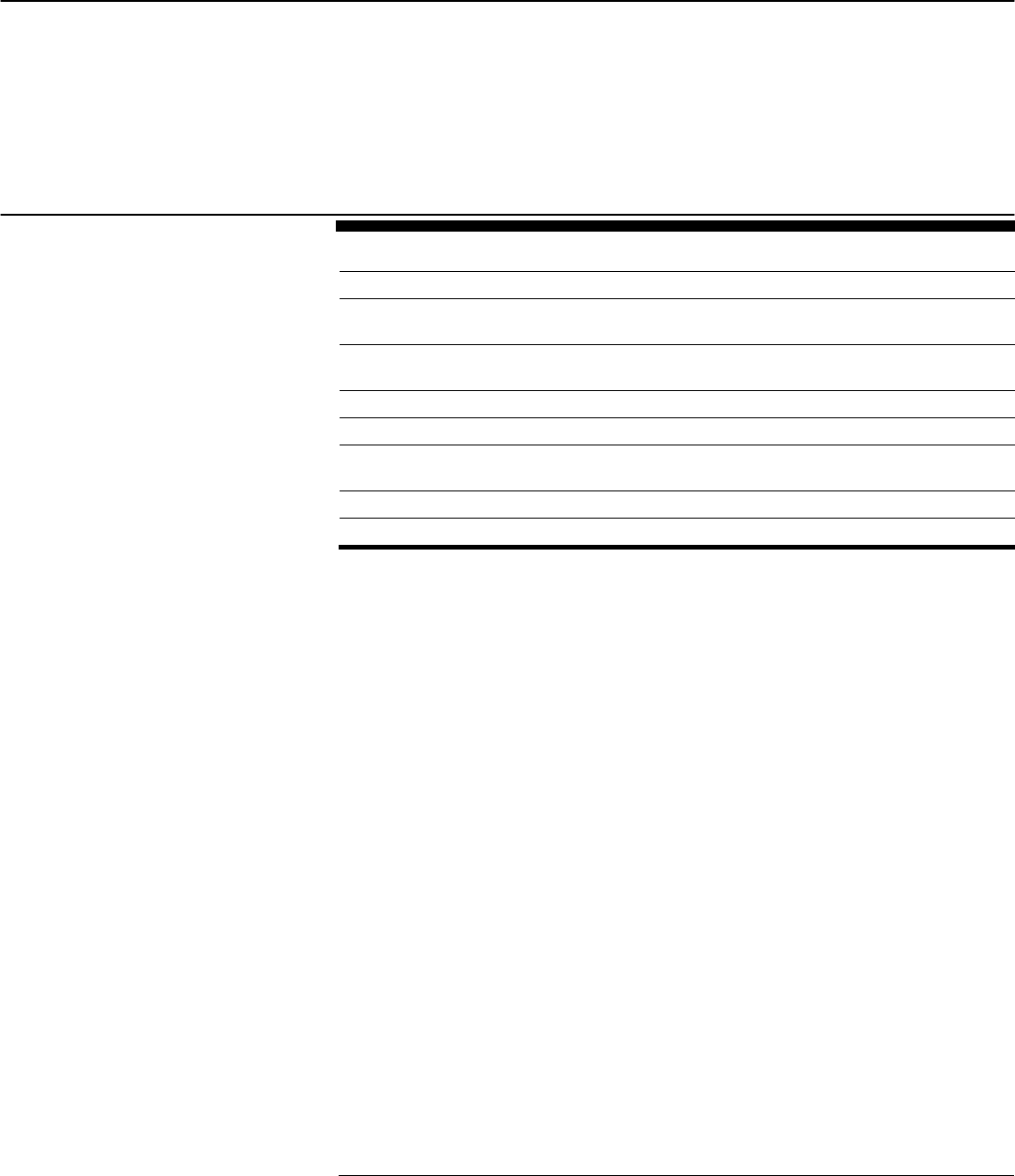

From fiscal years 2003 through 2012, state funding for all public colleges

decreased, while tuition rose. Specifically, state funding decreased by 12 percent

overall while median tuition rose 55 percent across all public colleges. The

decline in state funding for public colleges may have been due in part to the

impact of the recent recession on state budgets. Colleges began receiving less of

their total funding from states and increasingly relied on tuition revenue during

this period. Tuition revenue for public colleges increased from 17 percent to 25

percent, surpassing state funding by fiscal year 2012, as shown below.

Correspondingly, average net tuition, which is the estimated tuition after grant aid

is deducted, also increased by 19 percent during this period. These increases

have contributed to the decline in college affordability as students and their

families are bearing the cost of college as a larger portion of their total family

budgets.

Public College Revenue from State Sources and Tuition, Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012

GAO found that federal support for higher education is primarily targeted at

funding student financial aid— over $136 billion in loans, grants, and work-study

in fiscal year 2013—rather than at programs involving states. GAO identified

several potential approaches that the federal government could use to expand

incentives to states to improve affordability, such as creating new grants,

providing more consumer information on affordability, or changing federal student

aid programs. Each of these approaches may have advantages and challenges,

including cost implications for the federal government and consequences for

students.

View GAO-15-151. For more information,

contact Melissa Emrey-Arras at (617) 788-

0534 or [email protected].

Page i GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Letter 1

Background 2

From Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012, State Funding for Public

Colleges Decreased, while Tuition and Out-of-Pocket Costs for

Students Increased 7

State Policies Related to College Affordability Have Mixed Results 13

Current Federal Higher Education Programs Engaging with States

Are Limited, but Various Approaches Could Help Expand

Federal Incentives to States to Improve College Affordability 20

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 28

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 29

Overview 29

Data Analysis 30

Appendix II Trends in State Grant Aid to Students and Sources of Revenue for

Public Colleges 34

Appendix III Bibliography 36

Appendix IV Related GAO Products

39

Appendix V GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 40

Tables

Table 1: Number of Public, Private Nonprofit, and For-Profit

Colleges and Enrollment by Type, School Years 2002-

2003 and 2011-2012 6

Table 2: Examples of State Policies Related to Affordability at

Public Colleges 14

Table 3: Public College Revenue by Source in 2012 Constant

Dollars from Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012 35

Contents

Page ii GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Figures

Figure 1: Public Higher Education Funding Relationships, 2012 4

Figure 2: Revenue for Public Colleges, by Source, Fiscal Years

2003 through 2012 9

Figure 3: Public College Revenue from Tuition and State Sources,

Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012 10

Figure 4: Published In-State Tuition and Fees for All Public

Colleges in 2012 Constant Dollars, School Years 2002-

2003 through 2011-2012 11

Figure 5: Estimated Average Net Tuition and Fees by College

Type and Student’s Income Group in 2012 Constant

Dollars, School Years 2003-2004 and 2011-2012 12

Figure 6: Estimated Ratio of State Need-Based and Merit-Based

Grant Aid at Public Colleges, School Years 2003-2004

through 2011-2012 13

Figure 7: State-by-State Shifts in Need-Based Aid, from School

Years 2003-2004 through 2011-2012 34

Abbreviations

Education U.S. Department of Education

ERIC Education Resources Information Center

FTE Full-time equivalent

GEAR UP Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for

Undergraduate Programs

IPEDS Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data

System

LEAP Leveraging Educational Assistance Partnership

NASSGAP National Association of State Student Grant and Aid

Programs

NPSAS National Postsecondary Student Aid Study

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

December 16, 2014

The Honorable Tom Harkin

Chairman

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chairman:

The rising costs of higher education have led to widespread concern that

college is becoming unaffordable for many students and their families. To

help cover the cost of attending college, in fiscal year 2013, the U.S.

Department of Education (Education) provided over $136 billion in

assistance to students through loans, grants, and work study programs.

In addition to these forms of federal financial aid, states play a key role in

promoting affordability in higher education in that they provide a

significant amount of financial support to public colleges and universities.

1

However, persistent state budget constraints have limited funding for

public colleges.

We were asked to examine how state policies have affected college

affordability and explore how the federal government can encourage state

support to help make public colleges more affordable for students and

their families. Specifically, we examined: (1) how state financial support

and tuition have changed at public colleges over the past decade, (2) how

states’ higher education policies have affected affordability, and (3) how

the federal government works with states to improve college affordability,

and what additional approaches are available for doing so.

In conducting this work, we analyzed trends in state funding for colleges,

state student aid, and tuition using public sector data from Education’s

Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National

Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), and the National Association

of State Student Grant and Aid Programs (NASSGAP) databases for the

fiscal year 2003 to 2012 time period (the most recent data available at the

time of our analysis). We assessed the reliability of these data by (1)

1

Throughout the report, we will refer to all publicly-funded institutions of higher education

as public colleges. In addition to public colleges, there are private colleges, which can be

nonprofit or for-profit.

Page 2 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

performing electronic testing of required data elements, (2) reviewing

existing information about the data and the system that produced them,

and (3) interviewing agency officials or organizational representatives for

more information when needed. We determined that the data were

sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. We also identified

academic studies published in approximately the last 3 years (January

2011 through April 2014, when we conducted the literature search) that

are based on original research and that discuss the relationship between

state-level higher education policies and college affordability. We

assessed the quality of these studies by evaluating their research

methods and determined that 23 studies were sufficiently reliable for use

in our report. In addition, we met with six academic researchers who had

recently published studies relevant to state higher education policy or

college affordability and were recognized as experts in their field. We also

met with a total of 19 organizations involved in higher education issues,

some of which focus on sponsoring and conducting policy research, and

others that represent public colleges—including community colleges,

state colleges and universities, and public land grant universities—and all

50 states, as well as organizations that represent students.

2

See

appendix I for more information on our selection criteria and other aspects

of our methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from February to December 2014 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Higher education provides important private and public benefits, and

multiple parties are involved in financing higher education costs. In terms

of private benefit, students may seek a postsecondary degree as a key to

a better economic future. In addition to providing such private benefits,

higher education has also been crucial to the development of the nation’s

cultural, social, and economic capital. In particular, higher education helps

2

Throughout this report, we refer to the collective group of 25 academic experts, research

organizations, and advocacy organizations as “experts and organizations,” unless

otherwise specified.

Background

Page 3 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

maintain the nation’s competitiveness in a global economy by providing

students the means to learn new skills and enhance their existing

abilities. The federal government, states, students, and colleges, in turn,

all play important roles in financing higher education costs, thereby

influencing affordability (see fig. 1). Affordability is an important factor

affecting whether students access and complete degrees, and is

commonly thought of as the cost of higher education relative to student or

family income.

3

3

Additionally, some studies may factor returns on investment in college, such as

increased future earnings potential, into measures of affordability. For example, a recent

National Bureau of Economic Research study suggests that the benefits of higher

education, as indicated through earnings premiums for college graduates vs. non-

graduates may have increased over the past few decades. See National Bureau of

Economic Research, Making College Worth It: A Review of Research on the Returns to

Higher Education (Cambridge, MA: May 2013). We did not analyze earnings data as part

of this review.

Page 4 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Figure 1: Public Higher Education Funding Relationships, 2012

Note: Arrow thickness is scaled to fiscal year 2012 (or school year 2011-2012, where applicable)

funding levels. State funding for colleges includes appropriations and grants and contracts for

research. Federal and state aid arrows represent aid to undergraduates at public colleges. Federal

grants to states include only higher education programs related to college affordability. Land-grant

appropriations and federally funded research projects are included as part of the funding from the

federal government to public colleges. Benefits from tax credits and deductions for higher education

are not included.

The Department of Education was created in part to strengthen the

federal government’s commitment to assuring access to equal

educational opportunity. To that end, the federal government offers

several forms of financial aid to students and families through multiple

programs authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965,

as amended. These programs include the William D. Ford Federal Direct

Loan program, the Federal Pell Grant program (Pell Grants), Federal

Perkins Loans, and Federal Work-Study, and they are available at all

Federal Role

Page 5 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

eligible institutions of higher education, including both public and private

colleges.

4

In fiscal year 2013, Education provided over $136 billion in

financial aid to students, including loans and grants.

5

Some aid is targeted

toward low-income students based on their financial need. For example,

in fiscal year 2013, Education provided over $32 billion in Pell Grants to

eligible low-income students. In addition to funding for student aid,

Education provides higher education funding for states and colleges.

Funding for states includes two grant programs to support increased

access for low-income students: 1) the Gaining Early Awareness and

Readiness for Undergraduates Programs (GEAR UP) and 2) the College

Access Challenge Grant Program. The federal government also provides

funding to colleges for institutional development and grants and contracts

for research projects.

The states’ role in higher education begins with establishing public

colleges. In addition, states have been a significant source of revenue for

public colleges through state appropriations for operating expenses.

States may also fund public colleges through grants or contracts for

activities such as research projects. In addition to state funding for

colleges, most states have grant programs that provide financial aid

directly to students.

6

State grant aid can be allocated based on financial

need; merit, such as grades or test scores; or a combination of both.

Public colleges charge tuition and fees, and may also provide aid to

students depending on the college’s financial aid programs. These

colleges are generally administered by publicly elected or appointed

officials and are supported primarily by funding from federal, state, and

local sources—in addition to revenue from tuition and fees. They can also

differ in type, length of degree programs, and mission. For example, while

4

See GAO, Higher Education: Improved Tax Information Could Help Families Pay for

College, GAO-12-560 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2012) for more information on financial

assistance programs for students.

5

Generally, while financial assistance provided through loans must be repaid, grants do

not need to be repaid.

6

According to information from the National Association of State Student Grant and Aid

Programs, some states may also provide financial assistance to students through loan

programs.

State Role

Public Colleges

Page 6 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

some public colleges may offer 2-year associate’s degree programs,

others offer 4-year bachelor’s degree programs. As of the 2011-2012

school year, there were more than 2,000 public colleges that enrolled

over 11 million students, which represented 67 percent of total college

enrollment across all college types, including private nonprofit and for-

profit colleges in the United States.

7

Moreover, enrollment at public

colleges increased by almost 2 million students from school years 2002-

2003 through 2011-2012 (see table 1).

Table 1: Number of Public, Private Nonprofit, and For-Profit Colleges and Enrollment by Type, School Years 2002-2003 and

2011-2012

2002-2003 2011-2012

Number of Colleges Enrollment Number of Colleges

b

Enrollment

Public colleges

b

All public colleges 2,269

a

9,258,608 2,056 11,123,626

Public 4-year colleges 664 5,474,181 703 6,797,623

Public 2-year colleges 1,218 3,710,468 1,091 4,276,113

Private nonprofit colleges

All private nonprofit colleges 2,305 2,893,458 1,950 3,482,156

Private nonprofit 4-year colleges 1,789 2,815,835 1,658 3,420,534

Private nonprofit 2-year colleges 327 57,928 197 47,303

For-profit colleges

All for-profit colleges 2,949 817,156 3,553 2,047,844

For-profit 4-year 375 341,490 750 1,258,784

For-profit 2-year 829 239,996 1,077 489,042

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). | GAO-15-151

a

The “All colleges” categories include data for less than 2-year colleges

b

Enrollment figures represent full-time equivalent enrollment for undergraduate and graduate

students

Aside from federal, state, and local funding, colleges also collect revenue

through tuition and fees charged to students. The published tuition and

fees can be referred to as the “sticker price” and do not necessarily reflect

what students and families actually pay once financial aid has been taken

into account. In contrast, net tuition and fees reflect the out-of-pocket

7

Throughout the report, enrollment figures represent full-time equivalent enrollment for

undergraduate and graduate students.

Students and Families

Page 7 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

expenses for students and families in that they represent tuition and fees

net of all grant aid received by the student.

8

Students may receive grant

aid from the state, the federal government, or the college they are

attending.

In the decade spanning fiscal years 2003 to 2012, state funding provided

to public colleges decreased, both overall and when measured per

student.

9

Specifically, state funding for public colleges decreased by 12

percent overall, from $80 billion in fiscal year 2003 to $71 billion in fiscal

year 2012.

10

Most of the funding that public colleges receive from states is

in the form of appropriations (funds provided by state appropriations acts

for current operating expenses), while the rest of the funding from state

sources is in the form of grants and contracts that are identified for a

specific project or program.

The reductions in state funding to public colleges are even more

significant when enrollment levels are taken into account. The number of

8

We use the term out-of-pocket costs to describe tuition and fees after grant aid is

deducted. We do not deduct loans from these costs, as they generally have to be repaid.

There may be other expenses associated with attending college, in addition to tuition and

fees, such as living expenses, which we did not analyze in this report.

9

Fiscal year in the IPEDS financial data refers to the institutional fiscal year, and therefore

may vary across institutions. Each survey year the participating colleges report data from

the last fiscal year that ended on or before October 31.

10

All financial data presented in this report are adjusted for inflation and presented in

constant 2012 dollars unless otherwise noted.

From Fiscal Years

2003 through 2012,

State Funding for

Public Colleges

Decreased, while

Tuition and Out-of-

Pocket Costs for

Students Increased

State Funding for Higher

Education Decreased by

12 Percent Overall and by

24 Percent per Student

Page 8 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

students enrolled in public colleges rose by 20 percent from school year

2002-2003 to school year 2011-2012. Correspondingly, median state

funding per student declined 24 percent—from $6,211 in fiscal year 2003

to $4,695 in fiscal year 2012.

11

This trend has been driven mostly by 4-

year colleges, which experienced faster enrollment increases and steeper

declines in median state funding per student than 2-year colleges.

State funding declines may be attributable, in part, to prevailing economic

conditions and competing state budget priorities. Likewise, 19 of 25

experts and organizations we interviewed cited the 2007 to 2009

recession as a factor that directed trends in state funding. Several of

these experts and organizations described public higher education as the

“balance wheel of state economies,” where states reduce higher

education funding during constrained economic times, in part because

public colleges can use tuition as an additional funding stream unlike

other program areas that do not have alternative sources of revenue. Our

analysis of funding trends corroborates this characterization by showing

that state funding for public colleges gradually increased between fiscal

years 2005 and 2008, but began steadily declining in fiscal year 2008

during the most recent recession until fiscal year 2012, while tuition

revenue began climbing at a faster pace to fill the gap. These reductions

may have been mitigated to some extent by the Recovery Act.

12

Of the 19

experts and organizations we spoke with about the Recovery Act’s effect

on state support for higher education, 16 cited it as having influenced

higher education funding levels of which 7 believed the effect was short-

term. In addition to economic conditions, 19 of 25 experts and

organizations we interviewed cited competing state budget priorities, such

as healthcare and K-12 education, as a factor in declining state funding

for higher education. State funding trends have contributed to shifting

11

To calculate state funding per student, we divided total state funding by total full time

equivalent (FTE) enrollment for all public colleges. The number of FTE students is

calculated based on fall student headcounts as reported by the college to IPEDS. The full-

time equivalent (headcount) of the college’s part-time enrollment is estimated by taking a

portion of the part-time headcount and adding it to the full-time enrollment headcounts to

obtain an FTE for all students enrolled in the fall.

12

The Recovery Act created the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, which provided funds for

states to use to restore state support for elementary, secondary, and postsecondary

education. States were required to agree to meet maintenance of effort requirements as a

condition for receiving these funds. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009,

Pub. L. No. 111-5, div. A, tit. XIV, § 14005(d)(1), 123 Stat. 115 , 282-283.

Page 9 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

public colleges’ share of revenue away from state sources and toward

tuition (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Revenue for Public Colleges, by Source, Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. “Tuition” includes revenues from all

tuition and fees assessed against students, net of refunds, discounts and allowances, for educational

purposes. “Local” sources refer to funds provided and grants made by local government. “State”

sources refer to funds received by colleges through state appropriations laws or through grants and

contracts from state government agencies. “Federal” sources include appropriations for meeting

current operating expenses, grants, contracts, and federal grant aid to students such as Pell Grants.

“Other sources” include private gifts, grants and contracts; sales and services of educational

activities; auxiliary enterprises; hospital revenues.

From fiscal years 2003 to 2012, revenue from state sources shrunk from

32 percent of total revenue to 23 percent. Meanwhile, growth in tuition

revenue outpaced that of all other types of revenue over this period,

increasing from 17 percent to 25 percent and making tuition the top single

source of revenue for public colleges. In contrast, shares of federal, local,

and other revenue sources remained relatively stable. Total revenue

figures from each source are displayed in appendix II. By fiscal year

2012, tuition had overtaken state funding as a source of revenue for

public colleges (see fig. 3).

Page 10 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Figure 3: Public College Revenue from Tuition and State Sources, Fiscal Years 2003 through 2012

Notes: “Tuition” includes revenues from all tuition and fees assessed against students, net of refunds,

discounts and allowances, for educational purposes. “State” sources refer to funds received by

colleges through state appropriations laws or through grants and contracts from state government

agencies.

Published tuition prices and out-of-pocket costs increased for students in

all income quartiles both at 4-year and 2-year public colleges, making

college less affordable for students and families. Median published tuition

prices for in-state students increased by 55 percent from about $3,745 in

school year 2002-2003 to $5,800 in school year 2011-2012 (see fig. 4).

13

Though tuition is typically higher at 4-year colleges than at 2-year

colleges, the increase over the period was similar between the two types

of colleges: both increased by about 54 percent. Median published tuition

also increased for out-of-state students during this period, though less

dramatically than for in-state students, rising by 31 percent from the 2002-

2003 school year to the 2011-2012 school year.

13

All tuition figures cited in this report also include fees. Fees include all fixed sum

charges that are required of a large proportion of all students.

Median Published Tuition

Prices Have Increased by

55 Percent and Average

Out-of-Pocket Costs Have

Increased 19 Percent

since Fiscal Year 2003

Page 11 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Figure 4: Published In-State Tuition and Fees for All Public Colleges in 2012 Constant Dollars, School Years 2002-2003

through 2011-2012

Note: All figures are adjusted for inflation and are presented in constant 2012 dollars.

Published tuition prices do not necessarily indicate actual costs incurred

by students and families, in part because grant aid can help reduce out-

of-pocket costs. Thus, when all grant aid is taken into account, out-of-

pocket costs for students, or estimated average net tuition, increased by

19 percent across all public colleges from $1,874 in the 2003-2004 school

year to $2,226 in the 2011-2012 school year.

14

The changes in estimated

average net tuition vary by student’s income quartile and college type

14

Estimates of out-of-pocket costs are presented as averages and are therefore not

comparable to published tuition estimates, which are presented as medians. The

estimated out-of-pocket costs are based on the NPSAS sample and subject to sampling

error. Unless otherwise noted, all percentage estimates in this report have 95 percent

confidence intervals of within +/- 8 percentage points of the percent estimate, and other

numerical estimates have confidence intervals within +/- 8 percent of the estimate itself.

See appendix I for additional information on sampling error.

Page 12 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

(see fig. 5).

15

In particular, the increases in average net tuition are largest

for students in the higher income quartiles attending 4-year public

colleges.

Figure 5: Estimated Average Net Tuition and Fees by College Type and Student’s Income Group in 2012 Constant Dollars,

School Years 2003-2004 and 2011-2012

Notes: All figures are adjusted for inflation and are presented in constant 2012 dollars. Net tuition is

tuition and fees after all grant aid is deducted, including all merit-based, need-based, combination,

and other types of grant aid provided to students from local, state, federal, private, non-profit,

institutional, and other sources.

While most state grant aid to students is need-based, our analysis shows

a gradual shift toward merit-based aid from school years 2003-2004 to

15

Net tuition is tuition and fees after all grant aid is deducted, including all merit-based,

need-based, combination, and other types of grant aid provided to students from local,

state, federal, private, non-profit, institutional, and other sources. Income quartiles in this

report follow the standard NPSAS methodology of calculating quartiles separately for

dependent and independent students. Income for dependent students is typically parents’

income, while for independent students it is their own income in addition to that of a

spouse, if applicable.

Page 13 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

2011-2012 (see fig. 6). As a result, states are targeting a smaller portion

of their estimated available grant aid to students with the greatest

financial need. Some of the experts and organizations we interviewed

noted that the growth in merit-based aid may be related to its political

popularity, especially among state legislators. Appendix II shows state-by-

state shifts toward awarding either more need-based aid or less, between

school years 2003-2004 and 2011-2012.

Figure 6: Estimated Ratio of State Need-Based and Merit-Based Grant Aid at Public

Colleges, School Years 2003-2004 through 2011-2012

Notes: Need-based grant data in this figure also include combination grants that have both a need-

based and merit-based component. Merit-based grant aid includes any aid that does not take need

into consideration.

Students and their families are now bearing the cost of college as a larger

portion of their total family budgets. Across all students, the ratio of net

tuition to annual income has increased about one and a half times from

the 2003-2004 school year to the 2011-2012 school year, and was

greater for students in the lowest income quartile than those in the

highest quartile. Specifically, the ratio of net tuition to annual income was

about four times higher for students in the lowest income quartile when

compared to those in the highest quartile. Combined, these factors make

attending college less affordable for students.

States, along with public colleges, have implemented various policies

related to college affordability, but their effects are mixed or unclear

according to the 23 studies we reviewed and the 25 experts and

organizations we interviewed. These policies include financial strategies

like investing in state grant aid and techniques aimed at reducing the time

it takes a student to complete their degree (see table 2).

State Policies Related

to College

Affordability Have

Mixed Results

Page 14 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Table 2: Examples of State Policies Related to Affordability at Public Colleges

Financial Policies Time-To-Degree Policies

Budget process, priorities, and rules Credit transfer programs/Articulation

agreements

State grant aid (merit, need-based,

hybrid)

b

Limits on credit accumulation

Performance-based funding

c

Defining “full time” as 15 credits

Tuition limits or freezes Guidance for completing degree requirements

Tuition differentiation and set-asides College preparation efforts/limiting need for

remediation

a

Fee waivers

d

Tuition refunds for timely completion

College cost containment and efficiency

Source: GAO analysis of information from academic experts, higher education organizations, and literature review results. | GAO-15-

151

a

Tuition differentiation refers to the practice of charging different tuition to different types of students,

commonly seen when public colleges offer different rates to in-state students and out-of-state

students. Tuition set-asides are when colleges reserve a portion of their tuition revenue to fund

financial aid programs, which may distribute aid on the basis of financial need.

b

Credit transfer programs and articulation agreements specify whether course credits transferred

between colleges are acceptable for meeting degree or program requirements.

c

Credit accumulation refers to earning college credits. Not all credits count toward degree or program

requirements.

d

Remediation is coursework for students lacking skills necessary to perform college level work at the

degree of rigor required by the college or program. We previously reported that students in remedial

education have relatively low chances of completing their degrees or certificates within 8 years. See

GAO, Community Colleges: New Federal Research Center May Enhance Current Understanding of

Developmental Education, GAO-13-656, (Washington, D.C.: September 2013).

As we noted previously, economic trends and competing budget priorities

can affect state funding for higher education, which in turn has

implications for affordability at public colleges. In addition, an individual

state’s budget policies may influence state spending patterns. One study

we reviewed tested whether certain state fiscal policies, such as balanced

budget requirements and debt limits, would reduce state spending on

higher education. That study suggests these policies did not have a

statistically significant relationship with state expenditures on public

higher education. However, the study did show a negative relationship

between another type of fiscal policy—tax and expenditure limits—and

the level of state spending on public higher education.

16

Specifically, in

16

See Serna, Gabriel R. and Gretchen Harris. “Higher Education Expenditures and State

Balanced Budget Requirements: Is There a Relationship?” Journal of Education Finance,

vol. 39, no. 3 (2014): 175-202.

Financial Policies

Page 15 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

states with tax and expenditure limits in place, such as those that limit the

amount of revenue a state can take in from taxpayers, spending on higher

education was about 3 percent lower than states without these types of

policies.

There is wide variation in state policies related to setting tuition, as each

state has its own higher education governance system that may delegate

the primary authority to the governor, state legislature, governing boards,

individual public colleges, or a combination of these stakeholders. Several

experts and organizations who commented on this topic said that when

tuition is set centrally by the state and colleges have less authority, there

are positive effects on affordability for students. Given recent economic

conditions, some states have negotiated agreements with their public

colleges to curb tuition hikes, at times in exchange for more state funding.

Most experts and organizations we spoke with—11 of 15 who commented

on this issue—said these limits on tuition growth do not usually have long-

term effects on improving affordability for students, or have negative

effects on affordability. However, in the case of Maryland, a few experts

and organizations said the state has successfully suppressed tuition

increases through cost efficiencies achieved by its public colleges, which

may result in more sustainable benefits for students.

Regardless of how tuition is set, it is clear that specific tuition levels

directly affect students. For example, two studies found that policies

allowing rising tuition negatively affected affordability for students at

public colleges in California, even when considering contributions from

financial aid.

17

In addition, some studies found that tuition levels can also

affect student behavior and decision-making. For example, results from a

survey of students at about 15 large public colleges found that an

estimated 73 percent of students reported buying fewer or cheaper

textbooks, and 46 percent reported skipping meals in response to

increased college costs.

18

Moreover, tuition levels may influence students’

17

See Jones, Jessika. “College Costs and Family Income: The Affordability Issue at UC

and CSU.” (Sacramento, Calif.: California Postsecondary Education Commission, Report

11-02, 2011) and Poliakoff, Michael, and Armand Alacbay. “Best Laid Plans: The

Unfulfilled Promise of Public Higher Education in California.” (Washington, D.C.: American

Council of Trustees and Alumni, 2012).

18

In addition to buying fewer or cheaper textbooks, this group of students reported

reading books on reserve. See Chatman, Steve. “Wealth, Cost, and the Undergraduate

Student Experience at Large Public Research Universities.” (Berkeley, Calif: Center for

Studies in Higher Education, University of California at Berkeley, 2011).

Page 16 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

decisions about whether to attend college at all. For example, two

nationwide studies of public colleges found that increased tuition levels

were associated with decreased enrollment.

19

Like tuition, state grant aid directly affects students in that it can reduce

their out-of-pocket expenses for college.

20

In addition, evidence from five

recent studies we reviewed suggests that state grant aid, both merit- and

need-based, has positive effects on enrollment.

21

For example, a study of

a state scholarship program in Washington suggests that receiving the

aid increased a student’s probability of enrolling in college by nearly 14 to

19 percentage points, depending on the cohort and controlling for other

factors.

22

This positive effect on enrollment may indicate that students

enroll because they perceive college to be more affordable. Additionally,

a study of selected scholarships in four states shows that the aid helped

students stay in college. Specifically, an additional $1,000 in aid received

was associated with a 2 to 7 percent increase in persistence—the

19

See Hemelt, Steven W. and Dave E. Marcotte. “The Impact of Tuition Increases on

Enrollment at Public Colleges and Universities.” Educational Evaluation and Policy

Analysis, vol. 33, no. 4 (2011): 435–457: and Titus, Marvin A. and Brian Pusser. “States’

Potential Enrollment of Adult Students: A Stochastic Frontier Analysis.” Research in

Higher Education, vol. 52, no. 6 (2011):555–571.

20

While grant aid in general directly affects students’ out of pocket costs, one academic

expert and one higher education organization we spoke with said that the availability of

federal financial aid may unintentionally provide colleges with the opportunity to raise

tuition knowing that eligible students would be able to cover it through financial aid. We did

not examine this assertion in the course of our work as we did not identify any studies on

this topic that met the criteria for our literature review. For a discussion of how federal

student loan limit increases relate to tuition levels, see GAO, Federal Student Loans:

Impact of Loan Limit Increases on College Prices Is Difficult to Discern, GAO-14-7,

(Washington, D.C.: February 18, 2014).

21

See Hemelt 2011; Rae, Brian. “2013 Alaska Performance Scholarship Outcomes

Report.” (Juneau, Alaska: Alaska Commission on Postsecondary Education, 2013); Scott-

Clayton, Judith. “On Money and Motivation: A Quasi-Experimental Analysis of Financial

Incentives for College Achievement.” Journal of Human Resources, vol. 46, no. 3 (2011);

Welbeck, Rashida et al. “Piecing Together the College Affordability Puzzle: Student

Characteristics and Patterns of (Un)Affordability.” (New York, New York: MDRC, 2014);

Zhang, Liang, Shouping Hu and Victor Sensenig. “The Effect of Florida’s Bright Futures

Program on College Enrollment and Degree Production: An Aggregated-Level Analysis.”

Research in Higher Education, vol. 54, (2013): 746–764.

22

See O’Brien, Colleen. “Expanding Access and Opportunity: The Washington State

Achievers Scholarship.” (Washington, D.C.: Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in

Higher Education, 2011).

Page 17 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

likelihood that students will continue their education, on average.

23

Regarding state grant aid programs, there is general consensus among

experts and organizations we interviewed that investing in need-based

grant aid is a more efficient use of resources than merit aid in that the aid

is targeted to those students who need it most. Specifically, 20 of 25

experts and organizations we spoke with said that prioritizing need-based

aid over merit-based aid is important for improving affordability.

Many states have established or are considering policies that financially

reward public colleges for progress toward performance goals, which

most experts and organizations we spoke with—19 of 25—said could

improve affordability for students. The link between these types of policies

(called performance-based funding) and college affordability depends on

the specific goals being measured. For example, goals such as targeting

college-provided aid to low-income students or moderating tuition

increases are more relevant to affordability than to other performance

outcomes. While the studies we reviewed on existing performance-based

funding policies do not examine their effect on affordability, they show

mixed results on their effectiveness in incentivizing desired outcomes in

other areas. For example, a study on performance-based funding in

Washington, a state policy that was designed to incentivize degree

completion, suggests that the policy did not affect the number of

Associates’ degrees that public colleges produced. However, the number

of certificates completed rose after the policy was introduced. The authors

noted the possibility that colleges were encouraged to award certificates

that could be completed more quickly.

24

In another case, a study of

performance-based funding in Tennessee suggests that the financial

incentive tied to the policy, even when doubled, was not associated with

increases in retention rates.

25

That is, the policy was not successful in

achieving the desired outcome, possibly because there was not enough

of a financial incentive to influence institutional outcomes.

26

Recently,

23

See Welbeck 2014.

24

See Hillman, Nicholas W., David A. Tandberg, and Alisa Hicklin-Fryar. “Evaluating the

impacts of ‘new’ performance funding in higher education.” Forthcoming.

25

Tennessee refers to this policy as outcomes-based funding, but for the purposes of this

report we use the term performance-based funding to refer to all policies that tie state

funding to how well a public college performs on state-determined metrics.

26

See Sanford, Thomas and James M. Hunter. “Impact of Performance-funding on

Retention and Graduation Rates.” Education Policy Analysis Archives, vol. 19, no. 33

(2011).

Page 18 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

however, Tennessee started channeling all of its higher education funding

through a performance-based system,

27

and this level of financial

commitment may be effective in shaping colleges’ behavior. Time may

also be a factor in whether performance-based funding policies are

successful incentives. For example, a recent, nationwide study of

performance-based policies shows that there is little evidence tying

performance funding to positive outcomes, in part because so few states

maintain their policies long enough to change colleges’ behavior.

28

Nevertheless, the study did suggest a positive outcome of performance-

based funding— increased degree completion in several states—but only

after states kept the policy in place for an average of 7 years.

29

As of early

2014, 30 states were in the process of implementing performance-based

funding policies or had already done so, according to a national

organization representing state legislatures. For many of these policies, it

is too soon to know whether they will be effective at improving

affordability or achieving other desired outcomes.

Experts and organizations also pointed to state policies that allow

students to make more efficient use of their time in college, which may

help them save on tuition costs. While much of the research we reviewed

did not specifically address state policies on timely degree completion, as

many of them are relatively new, there was general agreement among

those we interviewed that reducing the time it takes for a student to

complete their degree can help make college more affordable. Various

states have implemented policies or launched voluntary initiatives

encouraging students to take the appropriate number of credits for their

degree program—neither too few nor too many. For example, Hawaii’s

“15 to Finish” media campaign is designed to raise awareness that

students should take 15 credit hours per semester to graduate on time.

27

In addition, Tennessee recently established a program offering in-state high school

graduates two free years of education at the state’s community and technical colleges.

The results of this wide-reaching program remain to be seen.

28

See Tandberg, David A. and Nicholas W. Hillman. “State Higher Education

Performance Funding: Data, Outcomes, and Policy Implications.” Journal of Education

Finance, vol. 39, no. 3 (2014): 222-243 and Dougherty, Kevin J., Rebecca S. Natow, and

Blanca E. Vega. “Popular but Unstable: Explaining Why State Performance Funding

Systems in the US Often Do Not Persist.” Teachers College Record, vol. 114, no. 3

(2012): 1-41.

29

See Tandberg 2014. At the time of the study, less than a third of the states that had

implemented performance funding systems maintained their program for 7 years or more.

Time-to-Degree Policies

Page 19 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Several states have policies to limit credit accumulation so that students

do not take—and pay for—more courses than necessary to complete

their degree.

According to the experts and organizations we interviewed, states and

public colleges are also working to ensure students take and get credit for

courses that count toward their degrees. To that end, states play a role in

enabling credit transfer programs and articulation agreements

30

between

public colleges to ensure that students do not have to re-take courses

they have already passed and paid for at another college. We have

previously noted that students taking additional credits as a result of

being unable to transfer credits would likely have to pay additional tuition,

though the extent to which these costs are borne by the student, for

example, would vary depending on the student’s eligibility for financial

aid.

31

There are also state policies that establish dual enrollment programs that

allow high school students to begin earning college credits early, as well

as college preparation programs—like Indiana’s 21st Century Scholars —

that could help students avoid taking remedial college courses that may

not count toward a degree.

32

State aid programs may also help with

college preparation by raising awareness of the academic requirements

to get into college. For example, in a study of merit scholarships offered

to high school graduates in Alaska who planned to attend selected

colleges in-state, eligible students were prepared for a more efficient

college experience.

33

They took far fewer remedial courses and enrolled

in more total credit hours on average than did their non-eligible peers.

Specifically, the study shows that after one semester, the average

scholarship recipient would have accumulated 13.2 credit hours toward a

30

An articulation agreement is an agreement between or among colleges that specifies

whether course credits transferred between colleges count toward meeting specific

degree or program requirements.

31

See GAO, Transfer Students: Postsecondary Institutions Could Promote More

Consistent Consideration of Coursework by Not Basing Determinations on Accreditation ,

GAO-06-22 (Washington, D.C.: October 2005)

32

The National Center for Education Statistics defines remedial courses as those for

students lacking skills necessary to perform college level work at the degree of rigor

required by the institution.

33

See Rae 2013.

Page 20 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

degree compared to 8.5 hours for a non-recipient, which brings them

closer to a full-time schedule of 15 credit hours.

Another state or public college policy to minimize students’ time-to-degree

focuses on granting credit for knowledge gained outside of the classroom,

which can ultimately reduce the overall cost of college. This can include

taking tests to demonstrate knowledge or skills developed through work

experience or prior learning. According to a survey of public college

students at about 15 large public colleges, 22 percent of students chose

to take tests for course credit instead of paying to take the actual

courses.

34

Known as competency-based education, this effort has

recently gained traction at the national level, as Education recently invited

colleges to participate in a research study involving this type of policy.

34

See Chatman 2011.

Current Federal

Higher Education

Programs Engaging

with States Are

Limited, but Various

Approaches Could

Help Expand Federal

Incentives to States

to Improve College

Affordability

Page 21 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Current federal funding for higher education is primarily targeted at

supporting students rather than on collaborating with states on higher

education policies affecting affordability. In fiscal year 2013, for example,

Education provided over $136 billion directly to students through loans,

grants, and work-study to help cover the costs of higher education

through seven different federal programs. That same year, Education

spent a relatively small amount, $358 million, on two higher education

programs that we found could be related to college affordability and that

involve states: 1) the College Access Challenge Grant and 2) the Gaining

Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR

UP).

35

These two programs provide grants to states and are targeted at

increasing access and success for low-income students in higher

education:

• The College Access Challenge Grant program was a formula

matching grant that provided funding to states based, in part, on the

relative number of state residents between the ages of 5 and 17 and

between the ages of 15 and 44 who are living below the applicable

poverty line.

36

Funds could be used to provide information to students

and families on financing options for college, provide need-based

grant aid to students, and conduct outreach activities for students who

may be at risk of not enrolling in or completing college, among other

uses.

37

To receive grants under the College Access Challenge Grant,

states were required to maintain their funding commitment to higher

education—at a level equal to the average amount provided over the

5 preceding fiscal years for public colleges—through a maintenance

of effort provision.

38

States had the option to apply for a waiver from

35

In contrast to the funding system in higher education, there are over a dozen K-12

education programs where the federal government works with states, such as making

grants to states for providing education to children with disabilities under the Individuals

with Disabilities Education Act. Funding for these programs is sizable. For example, in

fiscal year 2013, Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education and

Education’s Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services provided over $36

billion combined in grants to state and local governments. See Office of Management and

Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year

2015 (Washington, D.C.: March 4, 2014).

36

20 U.S.C. § 1141(c).

37

20 U.S.C. § 1141(f).

38

The maintenance of effort provision also requires that states maintain funding for

financial aid to students attending private colleges. 20 U.S.C. § 1015f.

Federal Higher Education

Programs are Targeted

More at Student Financial

Aid than Programs

Involving States on

College Affordability

Page 22 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

this requirement.

39

In fiscal year 2013, $142 million was appropriated

for the program, and of this amount, only $72 million was provided to

states because not all states met the maintenance of effort

requirements for receiving grant funding, according to Education

officials.

40

Education’s authority to award grants under this program

expired at the end of fiscal year 2014, further limiting federal

incentives to states to improve affordability.

41

• The GEAR UP program provides competitive matching grants to

states, as well as to partnerships composed of local educational

agencies, colleges, and other community organizations or entities.

42

The program is intended to encourage grantees to provide support to

assist low-income students prepare for and succeed in postsecondary

education. State grantees are required to use GEAR UP program

funds for a variety of required activities, including providing

scholarships and encouraging students to enroll in rigorous

coursework to reduce the need for remedial coursework at the

postsecondary level, and grantees are also permitted to use grant

funds for certain other purposes. These activities could improve

affordability by helping students obtain financial aid to cover higher

education costs or reducing the amount of time necessary to complete

a degree. In fiscal year 2013, $286 million was appropriated for the

program, and of this amount, almost $123 million was provided for 34

state grant awards and over $163 million was awarded to partnership

grants.

In addition to the programs listed above, Education officials said that they

currently draw attention to college affordability through consumer

information and ad hoc communication such as letters to state governors,

39

20 U.S.C. § 1015f(c).

40

According to Education officials, 28 states received grant awards in fiscal year 2013,

which included 16 states that met maintenance of effort requirements, 6 states that

received waivers from these requirements, and 6 states that did not receive waivers but

demonstrated significant efforts to take corrective action towards meeting maintenance of

effort requirements. The term “states” here and in subsequent references to the College

Access Challenge Grant program include both states and territories.

41

20 U.S.C. § 1141(a).

42

20 U.S.C. §§ 1070a-21 – 1070a-28. Partnerships consist of one or more local

educational agencies, one or more degree-granting colleges, and not less than two other

community organizations or other entities such as businesses. Partnership grants must

support an early intervention component and may support a scholarship component.

Page 23 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

speeches at conferences, and speaking with state officials at other

venues.

Based on interviews with experts and organizations as well as our review

of Education documents and relevant literature, we identified three

approaches that could be used to incentivize states to improve college

affordability. While not mutually exclusive or exhaustive, our research

identified these possible approaches to incentivize state action: the

creation of new grant programs, informational activities, or changes to

federal student aid programs. Lessons learned from current or past

programs can be instructive in identifying potential advantages and

implementation considerations associated with these approaches.

Moreover, some experts and organizations cautioned that the approaches

could have cost implications for the federal government and

consequences for students.

A majority—18 out of 25—of experts and organizations we interviewed

cited federal grant programs, such as providing grants for state student

aid, as an approach that could be used to encourage state policies that

improve affordability.

43

The federal government uses grants to stimulate

or support a variety of activities at the state level, and our prior work has

shown that these grants represent a significant component of federal

spending.

44

Grants may have a matching component that requires the

grant recipient to provide funding along with the federal government.

Furthermore, grants have already been used in several higher education

programs, such as Leveraging Educational Assistance Partnership

(LEAP), GEAR UP, College Access Challenge Grant, as well as in K-12

education through programs such as Title I funding and Race to the

Top.

45

43

In addition, two experts and organizations mentioned the federal government could

develop a new program to provide a free 2-year college option for students attending

public colleges as a way of improving affordability.

44

See GAO, Grants to State and Local Governments: An Overview of Federal Funding

Levels and Selected Challenges, GAO-12-1016 (Washington, D.C.: September 25, 2012)

for more information on grants to state and local governments.

45

To improve educational programs for schools with high concentrations of students from

low-income families, Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, as

amended provides flexible funding to state and local educational agencies.

Several Potential

Approaches Were

Identified That Could Be

Used to Incentivize States

to Improve Affordability

Grants

Page 24 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Grants can help spur innovation or state-level investment, and they can

be a useful tool when states do not have sufficient resources to fully

support a certain activity that has public benefits. Both competitive and

formula grants have been used to support current and past state-level

education programs. In K-12 education, there are several grant programs

to support state and local education efforts. For example, Education spent

almost $14 billion on Title I grants to school districts in fiscal year 2013,

and our prior work has found that funds have supported a variety of

initiatives related to instruction in selected school districts.

46

We have also

found that competitive Race to the Top grants have supported the

development of teacher evaluation systems in 12 states.

47

For higher

education programs, the LEAP program provided formula matching

grants to states to fund state need-based student aid grant programs prior

to fiscal year 2011. According to a 2006 report, the LEAP program

provided almost $66 million in federal funding, and states provided $840

million in funding, which exceeded the amount they were required to

match, for need-based grant programs in fiscal year 2005.

48

When the

LEAP program was discontinued in fiscal year 2011, all states had a

need-based grant program for students, up from only 28 when the

program was first authorized as the State Student Incentive Grants in

1972.

49

To help ensure that federal funding does not replace state

spending, some grant programs have maintenance of effort provisions,

which generally require that states maintain a certain level of funding.

According to Education officials, maintenance of effort provisions are one

lever the department has for certain grant programs it administers to

directly influence state spending. They stated, for example, that these

provisions in the College Access Challenge Grant program contributed

toward affordability goals because they incentivized some states to

maintain their funding commitment to higher education with a relatively

46

See GAO, Disadvantaged Students: School Districts Have Used Title I Funds Primarily

to Support Instruction, GAO-11-595 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2011).

47

GAO, Race to the Top: States Implementing Teacher and Principal Evaluation Systems

despite Challenges, GAO-13-777 (Washington, D.C.: September 18, 2013).

48

Dushin, Jamie H. “Examining LEAP” (National Association of State Student Grant and

Aid Programs position paper, October 2006).

49

In its fiscal year 2011 budget request, Education proposed that the LEAP program be

eliminated because it had accomplished its objective of stimulating states to establish

need-based student grant programs and federal incentives in this area were no longer

required. See Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2011 Budget Summary and

Background Information (Washington, D.C.: February 2010).

Page 25 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

small investment from the federal government. Maintenance of effort

provisions were also used in Recovery Act funding for higher education,

and 16 out of 19 experts and organizations said that this funding helped

states alleviate budget cuts to higher education during the recession.

50

Of

this group, four attributed this trend specifically to the maintenance of

effort provision associated with the funding.

In creating grant programs, it is important to consider how the program

would be monitored and administered. Our prior grants management

work has identified several challenges associated with grants to state and

local governments, such as difficulty in ensuring grant funds are used

appropriately and lack of agency or recipient capacity.

51

There could be

additional challenges for grant programs with maintenance of effort

requirements. For example, Education officials also observed that states

may be more responsive to maintenance of effort provisions when larger

amounts of federal funding are associated with the provision, and funding

for the College Access Challenge Grant program was not large enough to

influence states to a significant degree. In addition, our prior work found

that maintenance of effort provisions have often been difficult to monitor,

and in 2009, we recommended that Education take further action to

enhance transparency associated with maintenance of effort provisions in

the Recovery Act.

52

Creating new grant programs would also have cost

implications for the federal government and could have consequences for

students. Three experts and organizations we spoke with cited limited

funding as a challenge associated with this option, and one organization

indicated that the matching requirements for grant programs could create

incentives for states to increase funding in some higher education

programs while reducing it in others, which could affect students.

50

There were some instances where given topics were not discussed at every interview

with experts and organizations.

51

Other challenges that we have previously identified with grants to state and local

governments include: effectively measuring grant performance, uncoordinated grant

program creation, and need for better collaboration. See GAO-12-1016.

52

See GAO, Temporary Assistance For Needy Families: State Maintenance of Effort

Requirements and Trends, GAO-12-713T (Washington, D.C.: May 17, 2012), and GAO,

Recovery Act: Planned Efforts and Challenges in Evaluating Compliance with

Maintenance of Effort and Similar Provisions, GAO-10-247 (Washington, D.C.: November

30, 2009).

Page 26 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Education proposed a new grant program in its fiscal year 2015 budget

request, the State Higher Education Performance Fund, as a possible

way to incentivize states. This competitive grant program would reward

states that have a strong record of investment and states that show a

commitment to increasing support for higher education. States would be

required to match federal grant funds, and resources would be allocated

to institutions based on performance formulas developed by states. This

program has not been authorized by law.

53

As mentioned previously, state

funding can be a significant source of revenue for public colleges, and

increased state support may have positive effects on affordability if public

colleges do not have to rely as much on revenue from tuition. However,

the ultimate effect of increased state support or maintenance of effort

requirements on college affordability depends on the extent to which

states or public colleges limit or refrain from increasing tuition.

Providing information for consumers or on best practices is another

approach to influence behaviors, thinking, or knowledge in certain areas.

Information can be provided through a variety of methods, including

public communication or training. Education has undertaken efforts to

disseminate information on affordability to current and prospective

students which could help them make decisions on which colleges—

including those that are state-supported—would provide a good value.

Education provides multiple sources of information, including the College

Navigator and College Scorecard websites, which help students compare

colleges based on various measures, such as costs.

54

Additionally,

Education is currently developing a college ratings system to provide

students with information on the affordability of individual colleges.

55

Depending on its design, a ratings system could encourage colleges to

improve on measures associated with affordability to garner a higher

53

Education officials said that while the Department has considered states’ capacity to

implement the proposed State Higher Education Performance Fund program, final

decisions, such as the criteria for state programs, have not been made pending

authorization of the program.

54

See http://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/for College Navigator website and

http://collegecost.ed.gov/scorecard/index.aspx for the College Scorecard website.

Education also provides information on state spending via a website, including state

funding for higher education and aid to students. See

http://collegecost.ed.gov/statespending.aspx.

55

In its fiscal year 2015 budget request, Education requested $12 million to support the

development and refinement of the college ratings system.

Information

Page 27 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

rating. One consideration with implementing this initiative may be

concerns about protecting student privacy. For example, we reported in

2010 that states were unclear whether they could disclose data on

individual college graduates to assess program performance without

violating requirements related to student privacy.

56

In particular, student

privacy could be a concern when linking a student’s education record to

their employment records even if earnings and other employment

outcome data could help assess college affordability.

According to Education officials, the department has used training to

disseminate best practices to state grantees for GEAR UP programs. If

certain state policies are shown to be effective in promoting affordability,

the federal government may be able to use similar methods of providing

information to encourage the adoption of promising practices across

multiple states. However, as mentioned previously, various state policies

on college affordability show mixed results and others have only recently

been implemented, limiting the extent to which best practices may be

available.

Nearly half —11 out of 25—experts and organizations identified modifying

federal student aid programs as an option for improving affordability, but

modifications could also potentially have negative consequences for

students. Such changes could affect multiple parties, including public

colleges that must meet certain eligibility requirements before they can

receive and disburse federal funds to students. These suggestions

generally fell into two categories:

• Tie a public college’s eligibility to participate in federal student aid

programs or the level of federal student aid its students receive to

certain state activities or the state’s level of investment in higher

education. For example, Pell Grant funding could be increased for

students attending public institutions in states that achieve certain

goals related to investment in higher education.

• Create incentives for students to complete their degrees on time, for

example through changing Pell Grant eligibility requirements, which

56

See GAO, Postsecondary Education: Many States Collect Graduates’ Employment

Information, but Clearer Guidance on Student Privacy Requirements is Needed,

GAO-10-927 (Washington, D.C.: September 27, 2010) for more information on federal-

state information sharing in higher education.

Changes to Federal Student

Aid Programs

Page 28 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

Education officials said would require a change in statutory

authorization.

Education officials, experts, and organizations noted a number of

challenges associated with modifying federal student aid programs. One

such concern is inadvertently reducing students’ access to federal

financial aid. Because students are the ultimate recipients of financial aid,

restricting the aid flowing through states or colleges that do not meet

certain requirements could have the unintended consequence of reducing

aid for some students. Moreover, one organization indicated that this type

of policy change could face resistance from states or colleges. Similarly,

tying financial aid to students’ progress toward a degree could also have

negative effects on students. Education officials noted that changing the

definition of full-time enrollment from 12 to 15 credit hours per semester

could disadvantage students who have difficulty handling an increased

course load, such as students who need to work during the school year to

pay for college costs.

We provided a draft of the report to the Department of Education for

review and comment. Education provided technical comments, which we

incorporated as appropriate. We are sending a copy of this report to the

Secretary of Education. In addition, the report is available at no charge on

the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact

me at (617) 788-0534 or [email protected]. Contact points for our

Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on

the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this

report are listed in appendix V.

Sincerely yours,

Melissa Emrey-Arras

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security

Agency Comments

and Our Evaluation

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 29 GAO-15-151 State Higher Education Policies

This report examines: (1) how state financial support and tuition have

changed at public colleges over the past decade, (2) how states’ higher

education policies have affected affordability, and (3) how the federal

government works with states to improve college affordability, and what

additional approaches are available for doing so.

In conducting this work, we analyzed trends in state funding for public

colleges, state student aid, and tuition using public sector data from

Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS),

National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), and the National

Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs (NASSGAP)

databases. We assessed the reliability of IPEDS, NPSAS, and NASSGAP

data by (1) performing electronic testing of required data elements, (2)

reviewing existing information about the data and the system that

produced them, and (3) interviewing the managing organizations where

additional information was needed. We determined that the data were

sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. Data from all types of

public colleges were included in the analysis, including 2-year, 4-year,

and less than 2-year colleges. However, when analysis is provided by

college type, less than 2-year colleges are included only in the totals.

Private and for-profit colleges were excluded from this analysis. To