Desiree Carver-Thomas and Linda Darling-Hammond

Teacher Turnover:

Why It Matters and

What We Can Do About It

AUGUST 2017

Teacher Turnover:

Why It Matters and

What We Can Do About It

Desiree Carver-Thomas and Linda Darling-Hammond

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT

Suggested citation: Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it

matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

The report can be found online at https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-turnover.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution—NonCommercial 4.0 International

License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Larry Rosenthal, Senior Lecturer of Public Policy at University of

California, Berkeley, for his insights and advice. We also thank the following LPI colleagues for their

valuable feedback: Leib Sutcher, Roneeta Guha, Tara Kini, and the entire Educator Quality team. We

thank Bulletproof Services and Penelope Malish for their editing and design contributions to this

project, and Lisa Gonzales for overseeing the editorial process.

Research in this area of work is funded in part by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating

support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora

Hewlett Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation.

External Reviewers

This report beneted from the insights and expertise of two external reviewers: Li Feng, Brandon

Dee Roberts Excellence Assistant Professor at Texas State University; and Jesse Rothstein, Professor

of Public Policy and Economics and Director of the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment

at University of California, Berkeley. We thank them for the care and attention they gave the report.

Any remaining shortcomings are our own.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT

Table of Contents

Executive Summary.................................................................................................................................. v

Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................1

Trends in Teacher Turnover .....................................................................................................................3

National Trends ..............................................................................................................................3

Regional and State-by-State Trends ...............................................................................................9

Subject-Area Turnover ................................................................................................................. 11

Turnover in Schools Serving Historically Underserved Students ................................................ 14

Turnover of Teachers of Color ..................................................................................................... 20

Predictors of Turnover ........................................................................................................................... 24

School Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 24

Teacher Characteristics .............................................................................................................. 25

Main Teaching Subject Area ....................................................................................................... 27

Teaching Conditions .................................................................................................................... 29

Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................................ 30

Policy Considerations ............................................................................................................................ 32

Compensation ............................................................................................................................. 32

Teacher Preparation and Support ............................................................................................... 33

School Leadership ...................................................................................................................... 34

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 34

Technical Appendix ............................................................................................................................... 35

Data............................................................................................................................................. 35

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 35

Endnotes ................................................................................................................................................. 43

About the Authors ................................................................................................................................. 48

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Rate of Leaving Teaching Has Increased .........................................................................3

Figure 2: Sources of Teacher Turnover, 2011–12 to 2012–13 ....................................................4

Figure 3: Occupational Status of Leavers .......................................................................................5

Figure 4: Factors Teachers Report as Being Very Important for Leaving Teaching ........................6

Figure 5: Factors Teachers Report as Being Very Important Reasons for Moving .........................6

Figure 6: Turnover Rates Vary by Region and District Type ......................................................... 10

Figure 7: Teacher Turnover Varies Widely by State ...................................................................... 11

Figure 8: Turnover Rates Vary by Primary Teaching Assignment ................................................. 12

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT iv

Figure 9: Teacher Turnover Is Greater in Title I Schools .............................................................. 15

Figure 10: Teachers in Title I Schools Stay Fewer Years ................................................................ 16

Figure 11: Teachers in Title I Schools Have Fewer Years of Experience ....................................... 16

Figure 12: Teacher Turnover Is Greater When Schools Serve Primarily Students of Color ............ 17

Figure 13: Teachers in Schools Serving Primarily Students of Color Stay Fewer Years ................ 18

Figure 14: Teachers at Schools Serving Primarily Students of Color Have Less

Overall Experience ........................................................................................................ 19

Figure 15: Teacher Leaving Rate, 1988–89 to 2012–13 ............................................................ 21

Figure 16: Teacher Moving Rate, 1988–89 to 2012–13 ............................................................. 21

Figure 17: Teacher Leaver and Mover Rates, 2012 ...................................................................... 22

Figure 18: Predicted Turnover Rate by Population of Students of Color ....................................... 25

Figure 19: Predicted Turnover Rate by Population of Students of Color and

Teacher Preparation Pathway ....................................................................................... 26

Figure 20: Predicted Turnover Rates by Subject Area .................................................................... 27

Figure 21: Predicted Turnover Rate by Highest District Salary ...................................................... 28

Figure 22: Predicted Turnover Rate by Teacher Report of Administrative Support ....................... 29

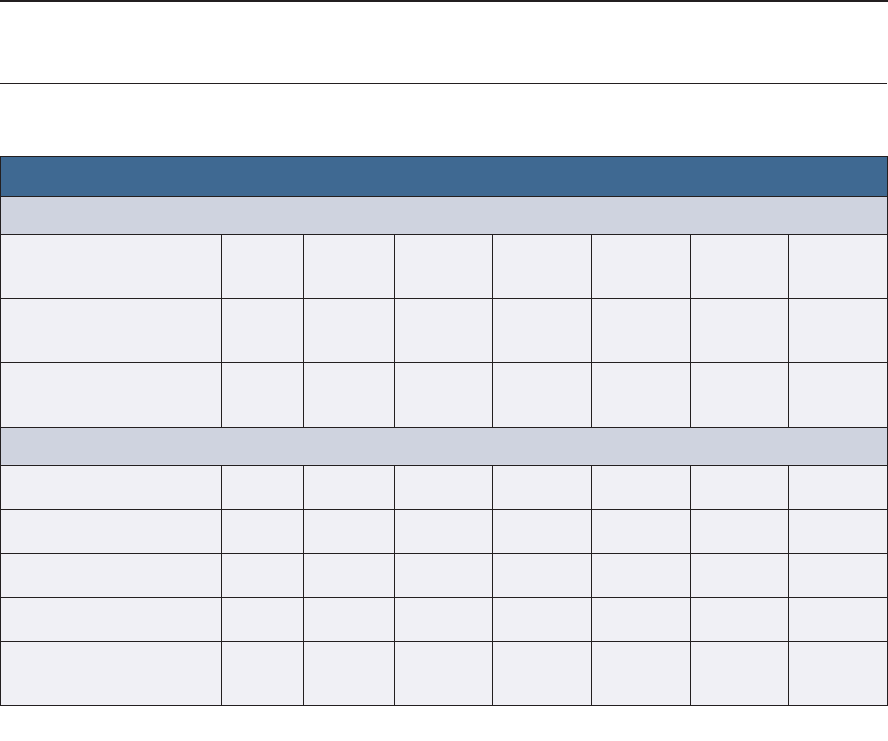

Table 1: Teacher Reasons for Leaving ...........................................................................................7

Table 2: Change in Proportion of Teachers in Selected Cities by

Teacher Race, 2000–12 .............................................................................................. 23

Table A-1: Independent Variable Means for Teachers Overall; Teachers of Color;

Mathematics, Science, and Special Education; and

Teachers from Alternative Pathways ............................................................................. 40

Table A-2: Logistic Regression Odds Ratios: Probability of Teachers Moving or Leaving ............. 41

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT v

Executive Summary

Growing teacher shortages nationally have made lling vacancies with qualied teachers increasingly

difcult. Curbing teacher turnover—that is, all teacher movement out of schools or out of the

profession—can go a long way toward solving shortages. About 90% of the nationwide annual demand

for teachers is created when teachers leave the profession, with two-thirds of teachers leaving for

reasons other than retirement. If school systems can address the factors that create high turnover,

they can reduce the demand for teachers who are in short supply.

Not only does turnover contribute to shortages, teacher movement out of schools and out of

teaching creates costs for the schools they leave behind. Estimates exceed $20,000 to replace

each teacher who leaves an urban school district. Most importantly, high turnover rates reduce

achievement for students whose classrooms are directly affected, as well as for other students in the

school.

Our analysis of nationally representative survey data from the 2012 Schools and Stafng Survey

and the 2013 Teacher Follow-up Survey reveals that the severity of turnover varies markedly

across the country:

• Total turnover rates are highest in the South (16.7%) and lowest in the Northeast (10.3%),

where states tend to offer higher pay, support smaller class sizes, and make greater

investments in education.

• Teachers of mathematics, science, special education, English language development, and

foreign languages are more likely to leave their school or the profession than those in other

elds. These are teaching elds that experience shortages in most states across the country.

• Turnover rates are 50% higher for teachers in Title I schools, which serve more low-income

students. Mathematics and science teacher turnover rates are nearly 70% greater in Title I

schools than in non-Title I schools, and turnover rates for alternatively certied teachers

are more than 80% higher.

• Turnover rates are 70% higher for teachers in schools serving the largest concentrations of

students of color. These schools are staffed by teachers who have fewer years of experience

and, often, signicantly less training to teach. Teacher turnover rates are 90% higher

in the top quartile of schools serving students of color than in the bottom quartile for

mathematics and science teachers, 80% higher for special education teachers, and 150%

higher for alternatively certied teachers.

• Teachers of color—who disproportionately teach in high-minority, low-income schools and

who are also signicantly more likely to enter teaching without having completed their

training—have higher turnover rates than White teachers overall (about 19% versus about

15%). While they leave at higher rates than White teachers generally, their turnover rates

are about the same as those of all other teachers in high-poverty and high-minority schools.

Teachers cite a number of reasons for leaving their school or the profession. The most frequently

cited reasons in 2012–13 were dissatisfactions with testing and accountability pressures (listed

by 25% of those who left the profession); lack of administrative support; dissatisfactions with the

teaching career, including lack of opportunities for advancement; and dissatisfaction with working

conditions. These kinds of dissatisfactions were noted by 55% of those who left the profession and

66% of those who left their school to go to another school.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT vi

Personal and nancial reasons were also cited, along with the desire to take another kind of job or to

retire.

Among the key variables that drive turnover

are the kind of preparation teachers have had

prior to entry and the kind of administrative

support they receive on the job. In an analysis of

predictors of turnover in which we controlled for

a large number of student, teacher, and school

characteristics, we found that:

• Teachers who enter the profession

through alternative certication

pathways—who have had less

coursework and student teaching, on average, than teachers who are prepared through

traditional programs—are 25% more likely to leave their schools and the profession, even

after controlling for their students, schools, and teaching conditions.

• Teachers of mathematics or science, special education, or foreign languages were much

more likely to leave their schools or the profession in comparison with elementary school

teachers. Holding all else constant, mathematics and science teachers have a predicted

turnover rate 37% greater than that of elementary school teachers, special education

teachers have a rate 46% higher, and foreign language teachers have a rate 87% higher.

• Teacher reports of a lack of administrative support have the strongest relationship with

teacher turnover. In a model controlling for other factors, teachers who strongly disagree

that their administration is supportive are more than twice as likely to leave their school or

teaching than teachers who strongly agree their administration is supportive.

• Controlling for other factors, teachers in districts with a maximum teacher salary greater

than $72,000 are 20% to 31% less likely to leave their schools than those in districts with

maximum salaries under $60,000.

Turnover was also higher for teachers in small schools and for those under 30 or over 50, as

compared to those in mid-career. Having controlled for school size and location and other student,

teacher, and school characteristics, no other teaching conditions proved to be signicant predictors

of teacher turnover.

Recommendations

To stem teacher turnover, federal, state, and district policymakers should consider improving the

key factors associated with teacher turnover: compensation, teacher preparation and support, and

school leadership.

Compensation

• Provide compensation packages that are competitive with those of other occupations

requiring similar levels of education and that are equitable across districts, so all schools

can compete in the labor market for well-prepared teachers.

• Offer service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs that reduce the debt burden

Among the key variables that

drive turnover are the kind of

preparation teachers have had

prior to entry and the kind of

administrative support they

receive on the job.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT vii

of teaching and encourage entry into the profession through high-retention pathways

that provide comprehensive preparation with strong clinical training. These programs

pay the cost of teacher preparation in exchange for a commitment to teach in a subject

or location of need for 3 to 5 years and can be targeted to the subjects and schools where

teachers are least likely to be well prepared and where turnover is greatest: mathematics,

science, special education, and in schools serving primarily students of color and students

in poverty.

Teacher Preparation and Support

• Establish other high-retention pathways into teaching that explicitly serve high-need

communities, such as teacher residency programs. Based on the medical residency

model, residents train in high-needs schools for an entire school year under the guidance

and supervision of a master teacher, while earning a credential and a master’s degree

from a partnering university. Most programs offer tuition assistance and a stipend for

living expenses, plus two years of mentoring after the training year. In exchange, residents

commit to teaching in the district for 3 to 5 years after their residency year. These programs

tend to have much higher than average teacher retention rates.

• Develop “Grow Your Own” teacher preparation models for hard-to-staff communities

that can recruit local high school students, paraprofessionals, after-school program staff,

or other local community members into teaching. These models capitalize on the fact that

teachers are more likely to stay and continue teaching in their own communities. Grow your

own models often underwrite the costs of teacher training through the kind of high-quality

preparation programs associated with improved teacher retention, while they also provide

supports for candidates to succeed.

• Provide high-quality mentoring and induction to beginning teachers that helps teachers

learn to teach effectively in high-need schools. High-quality induction programs that

reduce attrition include mentoring with observation and feedback, time for collaborative

planning with colleagues, a reduced teaching load, and a focus on high-leverage activities—

such as analyzing student work and discussing instructional strategies.

School Leadership

• Develop rigorous accreditation and licensure standards for principal training

programs aligned with research on effective school leadership, as well as systems for

regular program review by qualied experts.

• Fund residencies for principal training and state leadership academies that coordinate

mentoring and professional learning to develop school leadership capacity to build and

nurture collegial school settings that encourage teacher retention.

• Create systems and resources for developing robust leadership pipelines within districts

to ll positions districtwide and targeted to the schools in greatest need.

Effectively retaining teachers is crucial to ensuring there are enough well-prepared and committed

teachers to staff all of our nation’s schools and that the teachers in our classrooms have the

experience and expertise to effectively serve all students. Tailored policy interventions can play a

role in addressing the key factors that drive teachers from their schools, stabilizing and ultimately

improving the teacher workforce so that it can serve all students well.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT viii

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 1

Introduction

With the U.S. facing a national teacher shortage that is projected to grow substantially in the

coming years, school systems across the country are grappling with the challenge of building

and maintaining a high-quality teacher workforce for all students.

1

While school leaders and

policymakers might be tempted to solve shortages by focusing solely on teacher recruitment

strategies, a better approach begins with understanding teacher attrition and turnover.

A high rate of teacher attrition—that is,

teachers leaving the profession—is a primary

contributor to teacher shortages nationally.

The profession has a national attrition rate of

about 8% annually, and research shows that the

number of teachers leaving each year accounts

for close to 90% of annual teacher demand.

2

Furthermore, less than a third of national

teacher attrition is due to retirement. In other

words, each year schools nationwide must

hire tens of thousands of teachers as a result of beginning and mid-career teachers leaving the

profession.

Teacher turnover can also contribute to labor market imbalances. When teachers move between

schools, even if they stay in the profession, the effect on the schools they leave is essentially the

same as if they had left teaching altogether. In times of shortage, teachers who shift between

schools, known as “movers,” can further exacerbate hiring difculties in the hardest-hit schools.

Researchers agree that teacher turnover is to be expected, and, indeed, some amount of turnover

can be benecial as teachers nd schools or professions that are the right t. That said, teacher

turnover takes a toll on schools and students. In particular, when turnover contributes to teacher

shortages, schools often respond by hiring inexperienced or unqualied teachers, increasing class

sizes, or cutting class offerings, all of which impact student learning.

3

Research is clear that both

teacher inexperience and rates of turnover negatively impact student learning,

4

which means that

students in schools with high turnover and few experienced teachers are at a decided educational

disadvantage.

In addition, turnover impacts the achievement of all students in a school, not just those with a new

teacher, by disrupting school stability, collegial relationships, collaboration, and the accumulation

of institutional knowledge.

5

Financial costs also accrue when replacing teachers, with estimates

reaching $20,000 or more for each teacher who leaves an urban district.

6

The costs of teacher turnover are disproportionately borne by students in hard-to-staff schools,

typically those serving primarily students of color and students in poverty, which are more likely to

rely upon uncertied teachers who are often hired as a last resort when fully certied teachers are

not available. In 2013–14, the quarter of schools enrolling the most students of color nationally had

four times as many uncertied teachers as the quarter of schools enrolling the fewest students of

color. Uncertied teachers were also more common in schools serving the most students eligible for

free and reduced-price lunch than in those with the fewest.

7

Each year schools nationwide

must hire tens of thousands of

teachers as a result of beginning

and mid-career teachers leaving

the profession.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 2

This report uses data from the most recent nationally representative survey of U.S. teachers

(Restricted-Use Schools and Stafng Survey [SASS] 2011–12 and Teacher Follow-Up Survey [TFS]

2012–13) to investigate how turnover trends vary across teachers and schools. Given the signicant

role turnover plays in teacher shortages, this report discusses turnover trends in major subject areas

that commonly suffer shortages—mathematics, science, special education, and English language

development—as well as among teachers of color and in high-poverty and high-minority schools.

We begin with an overview of trends in teacher attrition and turnover, nationally and regionally. We

then look at these trends by subject area and by teacher and school characteristics. Next, we discuss

predictors of teacher turnover that have been surfaced in previous research and test them with the

most recent national data. We end with a discussion of policy considerations, based on research on

stemming teacher turnover.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 3

Trends in Teacher Turnover

Teacher turnover varies considerably across states and regions of the country, among and

within school districts, and among teachers of different types. Below, we discuss the variation in

turnover trends, including nationally; regionally; in math, science, special education, and English

language development; in schools serving students in poverty and students of color; and among

teachers of color.

National Trends

The percentage of teachers leaving the

profession—known as “leavers”—has increased

substantially over the past two decades: 5.1%

of public school teachers left the workforce in

1992, while 8.4% left in 2005. Attrition rates have

continued to hover around 8% since then (see

Figure 1).

8

The 3% increase in attrition rates is

not trivial: It amounts to about 90,000 additional

teachers needing to be hired across the U.S. each

year. In high-achieving school systems such as those in Finland, Singapore, and Ontario, Canada,

annual teacher attrition rates typically average as low as 3% to 4%.

9

If attrition rates in the U.S.

could be reduced by half to be more comparable with these systems, the national teacher shortage

could be virtually eliminated.

10

The percentage of teachers

leaving the profession has

increased substantially over the

past two decaeds.

Figure 1

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Source: National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey; Goldring, R., Taie, S., & Riddles, M. (2014).

Teacher Attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-Up Survey. National Center for Education Statistics.

Rate of Leaving Teaching Has Increased

PERCENTAGE OF TEACHERS

1988–89 1991–92 1994–95 2000–01 2004–05 2008–09 2012–13

■ Leavers ■ Movers

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 4

In addition to the 8% of teachers who leave the

profession each year, about 8% shift schools.

Thus, the overall turnover rate is currently

about 16%. Movers and leavers may leave their

schools or the teaching profession voluntarily or

involuntarily, and they may leave to retire or for

other preretirement reasons.

During 2012–13, when many schools were

being closed and many teachers were being

laid off during the Great Recession, there was a higher than usual rate of involuntary turnover, at

14%. (For context, less than 8% of turnover was involuntary in 2008–09.) Most of these teachers

attributed their involuntary moves to budget cuts, school closures, reduced student enrollment, and

school transfers. Almost all movers go on to regular teaching positions; the remaining few become

itinerant teachers who travel between school sites, long-term substitutes, or other nontraditional

teachers.

About 18% of total turnover (including movers and leavers) was due to retirement. Importantly,

more than two-thirds of all teacher turnover between the 2011–12 and 2012–13 school years

was voluntary, preretirement turnover (see Figure 2). The reasons for leaving a school can be

wide-ranging. One teacher might change schools, for example, because of unfavorable working

conditions, while another might leave to teach somewhere else as part of a family move.

In addition to the 8% of teachers

who leave the profession each

year, about 8% shift schools.

Thus, the overall turnover rate is

currently about 16%.

Figure 2

Involuntary

turnover, 14%

Retirement, 18%

Voluntary,

preretirement

leavers, 30%

Voluntary

movers, 37%

Stayers, 84% Turnover, 16%

67% of

turnover

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12 and

Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2012–13.

Sources of Teacher Turnover, 2011–12 to 2012–13

Where Do Teachers Who Leave the Profession Go?

Among those who left teaching entirely in 2012–13, about 38% retired (see Figure 3), but only

31% cited retirement as the major reason they left. Teachers who retired without claiming

retirement as a signicant reason might have taken an early-retirement package and gone on

to take another job or might have left for other reasons, but took retirement because they were

eligible. For example, a teacher may leave teaching because she moves to a new state and has

difculty transferring her teaching certication or pension plan to her new home state. If she

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 5

responds by retiring, she would be counted among retirees, despite not leaving with the intention to

retire. Others may have taken retirement because they were dissatised with teaching or in lieu of a

layoff or nonrenewal. About 12% of involuntary leavers went on to retire.

Aside from retirees, nearly 30% of leavers continued to work for a school or district outside of the

classroom, 9% left to take care of family members, and 8% took jobs outside of education. The

remaining leavers were unemployed, in college, disabled, working in education outside of k-12 or in

k-12 outside of a school or district, or working in some other unspecied occupation.

Teachers most often cite

dissatisfaction as a very important

reason for voluntarily leaving

the profession.

Figure 3

Retired

Working for a school or district, but not as a k-12 teacher

Caring for family members

Working outside of education

Unemployed

Other

Working in pre-K or postsecondary ed

College student

Disabled

Working in k-12 but not in a school or district

Note: Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2012–13.

Occupational Status of Leavers

PERCENT

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

Why Do Teachers Leave the

Profession?

According to their survey responses, teachers

most often cite dissatisfaction as a very

important reason for voluntarily leaving the

profession. (See Figure 4 for an overview and

Table 1 for disaggregated reports of each

reason category.) The most frequent area of

dissatisfaction cited by voluntary leavers in

2012–13 concerned testing and accountability

measures (25%), followed by unhappiness with the school administration (21%) and dissatisfaction

with the teaching career (21%), which likely has to do with many factors. Some of these teachers

may be among those who left to pursue another job (31%) and those who left for nancial reasons

(13%) as teachers could cite multiple reasons for leaving.

The next-largest group of leavers is made up of teachers who left for family or personal reasons that

include moving to a more conveniently located job, health reasons, and caring for family members.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 6

Figure 4

Figure 5

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Dissatisfaction

Family/personal reasons

Retirement

To pursue another job

Financial reasons

Note: Percentages do not add to 100 as teachers may select more than one reason for leaving.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Teacher Follow-up Survey, 2012–13.

Factors Teachers Report as Being Very Important for Leaving Teaching

PERCENT

55

43

31

31

18

Why Do Teachers Move Schools?

Voluntary movers also most commonly cite dissatisfaction as a very important reason for

voluntarily moving schools (see Figure 5). Among the two-thirds who leave for reasons of

dissatisfaction, the most frequent concerns are with school administration (33%), lack of inuence

on school decision making (29%), and school conditions, including facilities and resources (27%).

Financial reasons were separately cited by 27% of teachers.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Dissatisfaction

Family/personal reasons

To teach at another school

Financial reasons

Retirement benefits

Note: Percentages do not add to 100 as teachers may select more than one reason for moving.

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2012–13.

Factors Teachers Report as Being Very Important Reasons for Moving

PERCENT

66

52

48

27

4

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 7

Table 1

Family and personal reasons are also cited by 52% of movers as important reasons for leaving their

school; these reasons overlap with dissatisfactions, as respondents could choose more than one

response. These data do not provide more ne-grained responses that would distinguish between

teachers who leave for child-rearing purposes, to take care of an aging parent, to attend to their

own health issues, and so on.

The fact that 4% of movers cited retirement benets as a reason for leaving (although they did go

on to teach in another school) suggests that a small share of teachers are motivated to take these

benets when they are eligible and then nd another place to continue teaching.

While leaver and mover reports shed some light on reasons for turnover, they have a limited

capacity to denitively predict it, especially since the federal Teacher Follow-Up Survey cited here

asks only those who leave for their reasons in doing so. After all, teachers who choose to stay in

their classrooms and at their schools may experience many of the same challenges and frustrations

as those who decide to move or leave. In addition, the questions asked of movers and leavers do

not offer the opportunity for teachers to speak to the role of their preparation, or other key factors

associated with teacher turnover, in their decision making. We discuss these other reasons for

teacher attrition in a later section of this report.

Teacher Reasons for Leaving

Reasons Given for Leaving Overall Mathematics

& Science

Teachers

Special

Education

Teachers

ELD

Teachers*

Teachers of

Color

Teachers in

High-Poverty

Schools

Teachers in

High-Minority

Schools

Areas of Dissatisfaction

Dissatisfaction With Assessment and Accountability Issues

Dissatisfied because

of assessments and

accountability measures

25% 26 24 26 26 30 35

Dissatisfied because not

enough support to prepare

students for assessments

17% 18 14 4 18 24 25

Dissatisfied with

compensation tied to

student performance

8% 5 6 6 11 8 8

Dissatisfaction With Administrative Issues

Dissatisfied with the

administration

21% 13 14 6 22 18 15

Too many intrusions on

teaching time

18% 11 13 25 15 16 14

Discipline issues were an

issue at school

17% 10 10 26 19 18 17

Not enough autonomy in

the classroom

14% 7 6 12 15 12 10

Dissatisfied with lack of

influence over school

policies and practices

13% 10 8 4 14 12 9

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 8

Table 1: Teacher Reasons for Leaving (continued)

Reasons Given for Leaving Overall Mathematics

& Science

Teachers

Special

Education

Teachers

ELD

Teachers*

Teachers of

Color

Teachers in

High-Poverty

Schools

Teachers in

High-Minority

Schools

Dissatisfaction With Teaching Career

Dissatisfied with teaching

as a career

21% 12 15 12 19 18 16

Not enough opportunities

for leadership or

professional advancement

9% 7 7 2 9 6 5

Dissatisfaction With Working Conditions

Dissatisfied with job

description or assignment

12% 11 11 22 12 13 14

Dissatisfied with large class

sizes

10% 6 7 20 6 8 7

Dissatisfied with working

conditions (facilities,

classroom resources,

school safety)

9% 6 7 3 11 8 9

Personal or Life Reasons (43%)

Wanted to take a job more

conveniently located

11% 10 9 16 13 11 11

Other personal life reasons

(e.g., pregnancy/child care,

health, caring for family)

37% 33 42 42 40 37 41

Change of Career (31%)

Decided to pursue another

career

28% 22 23 31 29 25 24

Taking courses to improve

career opportunities within

the field of education

13% 9 13 3 19 11 10

Taking courses to improve

career opportunities

outside the field of

education

5% 5 4 0 5 3 3

Retirement (31%)

Decided to retire or receive

retirement benefits

31% 28 37 50 27 29 22

Financial Reasons ( 18%)

Wanted or needed a higher

salary

13% 11 16 3 11 1 9

Needed better benefits

8% 5 8 0 6 5 3

Concerned about job

security

7% 6 7 1 6 6 4

* The sample of ELD teachers is small. Interpret with caution.

Sources: National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12, and Teacher Follow-Up Survey,

2012–13.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 9

Regional and State-by-State Trends

There is wide variation among states and

regions in teaching conditions—such as salaries

offered, certication requirements, working

conditions, per-pupil spending, and a host

of other factors—that affect teachers and

students. For example, at the high end of the

spectrum, Wyoming teachers had higher than

average starting salaries of over $43,000 in

2013, and teachers on average earned 94% of

what other comparably educated professionals

in the state earned at the same age, education

level, and hours worked.

11

On the other end,

Arizona teachers had lower beginning salaries at just $31,874 and earned only 62% of what other

professionals in the state did at the same age, education level, and hours worked.

These estimates may actually overstate the comparability of teacher salaries with those of other

workers because studies nd that teachers often work considerably longer hours than required by

their contracts and do substantial work in the summer to prepare for the next school year.

12

Aside from the unique status of Wyoming, which has had signicant oil revenues in recent

years, salaries are typically highest in the Northeast and lowest in the South and West. Teaching

conditions also vary dramatically across regions. In the West, pupil-teacher ratios are especially

high, ranging between 18-to-1 and 24-to-1 in Colorado, Washington, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon,

Arizona, Utah, and California, from least to greatest. In the Northeast, pupil-teacher ratios are

much smaller, ranging from just 11-to-1 in Vermont to a high of 15-to-1 in Rhode Island.

13

(Note

that class sizes are always larger than pupil-teacher ratios, since teachers have other non-teaching

duties and time during the day.)

At 16.7% annually, the South has a particularly high turnover rate compared to the northeastern,

midwestern, and western regions, which average, at most, 13% annual turnover. Southern and

midwestern cities have the highest rates of teacher turnover, followed by southern suburbs, towns,

and rural areas (see Figure 6). The higher-spending Northeast averages the lowest turnover rates

across all district types, with about 10% turnover overall and less than 8% turnover in its towns and

rural areas. For most regions, turnover is higher in cities than in any other district type. By contrast,

in the West, turnover in cities and suburbs is lower than turnover in towns and rural areas.

At 16.7% annually, the South has

a particularly high turnover rate.

The higher-spending Northeast

averages the lowest turnover

rates, with about 10% turnover

overall.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 10

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Turnover Rates Vary by Region and District Type

Note: District types are based on 2000 Census population and geography information. For more information, see

Documentation to the NCES Common Core of Data Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey: School

Year 2009–10 (NCES 2008–332).

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey 2011–12,

and Teacher Follow-Up Survey 2012–13.

TURNOVER RATE

CITYOVERALL SUBURB TOWN RURAL

10.3%

12.0%

16.7%

12.1%

16.4%

17.3%

12.5%

9.2%

12.2%

15.8%

9.6%

7.7%

12.1%

14.3%

12.6%

6.8%

9.6%

14.7%

13.3%

11.0%

Figure 6

The variation in annual turnover is even greater

between states, ranging from just over 8% in

Utah to 24% in Arizona (see Figure 7). In almost

every state, the bulk of turnover is due to

preretirement leaving and moving. Retirement

represents less than a third of all turnover in

every state except for Oregon and New Jersey,

where retirement accounts for 37% and 44% of

turnover, respectively. In 30 states, retirement

turnover is 25% or less of all turnover.

In almost every state, the bulk of

turnover is due to preretirement

leaving and moving. Retirement

represents less than a third of all

turnover in every state except for

Oregon and New Jersey.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 11

Figure 7

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Note: States with fewer than 25 teachers surveyed were excluded (DC, HI, and WY). Three small New England states with

similar data patterns were combined (NH, RI, VT).

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12 and

Teacher Follow-up Survey, 2012–13.

Teacher Turnover Varies Widely by State

■ Retirement Leavers ■ Preretirement Leavers ■ Movers

TURNOVER RATE

AZ

NM

LA

TX

NV

MT

OK

MS

NC

DE

SC

AK

WI

MN

KY

IN

KS

CO

ND

VA

FL

MO

AL

AR

IA

MA

ID

TN

OH

GA

MI

SD

MD

OR

NY

CT

CA

NE

ME

WA

IL

PA

NJ

New England

WV

UT

Subject-Area Turnover

In recent years, there have been severe shortages of teachers qualied to teach mathematics,

science, special education, and English language development in schools across the country. High

teacher turnover rates can intensify these shortages, especially in hard-to-staff schools with few

resources to attract teachers from a limited pool of qualied teachers. As discussed below, research

suggests that the causes of these shortages differ among subject areas.

Turnover rates vary across subject areas, with the

lowest rates found among general elementary

teachers and humanities teachers. Mathematics,

science, and special education teachers have

higher turnover rates, exceeding 13% annually.

Teachers who primarily teach English to speakers

of other languages have an even higher turnover

rate of about 19%; this rate is driven especially

by movers

14

(see Figure 8).

Turnover rates vary across subject

areas, with the lowest rates found

among general elementary and

humanities teachers.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 12

Figure 8

Mathematics and science

American students have demonstrated declining achievement in mathematics and science, subjects

that are increasingly important in an economy driven by technological innovation.

15

According to

the most recent Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) results from 2015, the United

States scores well below average in mathematics, ranking 31st out of 35 Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The U.S. ranks 19th in science, with average

scores among this group.

16

U.S. performance on these international tests has dropped in these

subjects plus reading since 2000, when PISA was rst administered.

17

A well-prepared mathematics and science teacher workforce can support student achievement;

however, secondary mathematics and science positions have been historically difcult to ll.

18

Indeed, one recent national study showed that schools were about four times more likely to have

trouble lling mathematics and science positions than English positions. Compared to schools

not reporting these difculties, schools that reported difculties lling mathematics and science

positions were nearly twice as likely to have above-average teacher turnover rates the year before

having the vacancy.

19

When schools have trouble lling positions, they often rely on hiring

unqualied and inexperienced teachers, which undermines student achievement and contributes to

ongoing turnover.

20

There are two primary arguments for why mathematics and science teachers have higher turnover

rates than teachers in other subject areas: (1) opportunities for better-compensated positions

in other occupations as well as in other school districts, and (2) lack of teacher preparation. The

literature on mathematics and science teacher turnover offers evidence that these teachers leave

teaching because their skills give them access to higher-paying jobs.

21

In addition, scholars have

found that mathematics and science teachers often tend to have less teacher preparation than

teachers of other subjects—in part because many enter through alternative pathways, which are

associated with higher attrition rates.

22

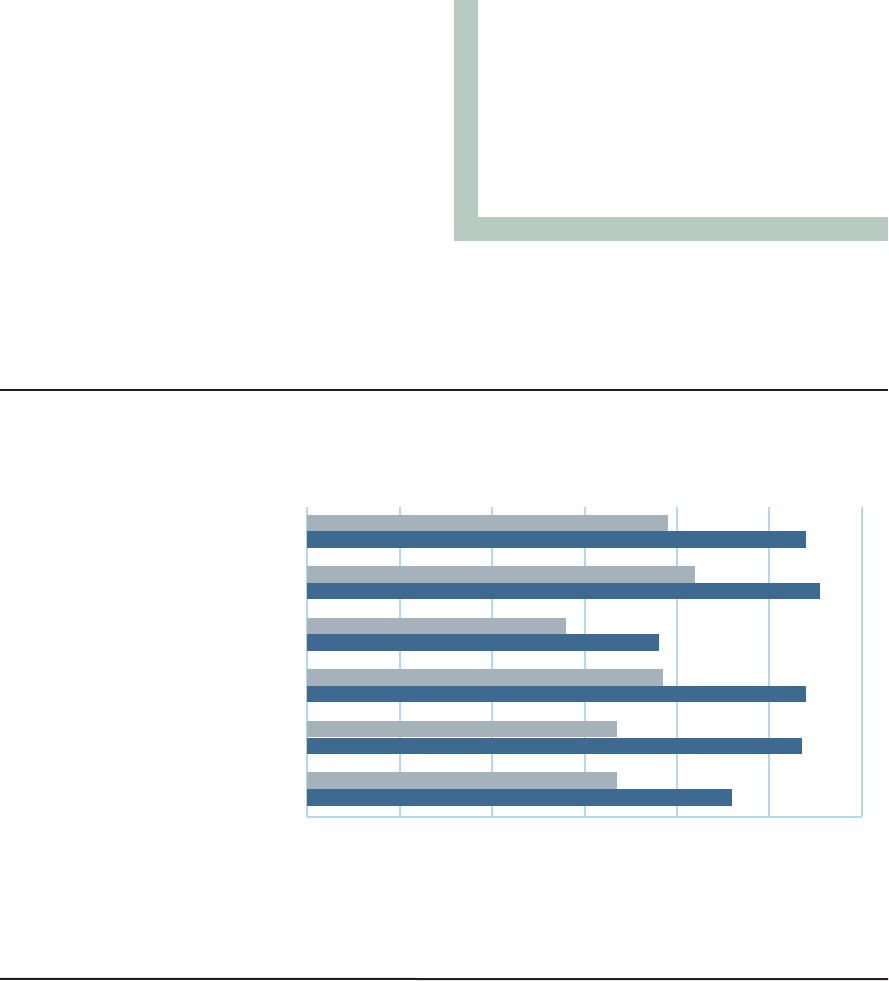

0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% 14% 16% 18% 20%

General elementary

Humanities

Mathematics/science

Special education

English language

development

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12.

Turnover Rates Vary by Primary Teaching Assignment

TURNOVER RATE

■ Leavers ■ Movers

4.9% 6.4%

5.3%7.3 %

6.1%7.2%

8.6%5.6%

6.9% 12%

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 13

Differences in attrition rates for mathematics and science teachers in comparison to teachers

in other subject areas are not statistically signicant overall; however, mathematics and science

teachers leave Title I schools at a signicantly higher rate than they leave non-Title I schools. In

Title I schools, the turnover rate for mathematics and science teachers is nearly 70% greater than it

is in non-Title I schools (17.8% versus 10.5%).

Additionally, in schools serving low-income students and students of color, mathematics and

science teachers are also more likely to have been certied via an alternative pathway. While the

characteristics of alternative certication pathways vary, these accelerated programs often require

fewer courses and less clinical experience than traditional programs do before participants become

teachers. In schools with the most students of color, fully 30% of mathematics and science teachers

entered teaching via an alternative pathway, compared to just 12% of mathematics and science

teachers at schools with mostly White students. Teachers who enter through such pathways often

lack the experience of student teaching and may also lack critical coursework in subject-specic

teaching methods and curricula that can undermine their initial teaching experiences.

Special education

Since federal law was passed in 1975 to ensure all students have access to a free and appropriate

education, the proportion of students who receive special education services has steadily grown.

23

When the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) went into effect, 8.3% of public school

children, ages 3 to 21, were served by the law. In 2012–13, that percentage rose to nearly 13%, a

55% increase over nearly 40 years. Schools need special education teachers who can meet the needs

of a variety of students, including those with autism, developmental delays, learning disabilities,

health impairments, and other disabilities.

24

Teacher shortages in special education have been severe and persistent. In every year of the 1990s,

more than 30,000 special education positions were lled by uncertied teachers, and in 2000–01,

over 47,000 (or 11%) of those lling special education positions were not certied to teach in

the subject area.

25

A recent study of teacher shortages found that, in 2015–16, 48 states plus the

District of Columbia reported special education teacher shortages, with these being the most severe

shortages for most states.

26

According to past research, two primary factors

drive special education teacher shortages: (1)

too few special education teachers are being

prepared, and (2) too many leave each year.

Importantly, difcult working conditions—such

as lack of administrative support, lack of

collaboration, and excessive paperwork—play

a key role in teacher decisions to leave the

profession or transfer from special education to

general education positions.

27

As illustrated in Figure 8, special education teacher turnover rates are greater than those of most

other categories of teachers. Special education teachers have about the same turnover rates in Title

I schools as they do in non-Title I schools. However, in high-minority schools, their turnover rates

In Title I schools, the turnover

rate for mathematics and science

teachers is 70% greater than it is

in non-Title I schools.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 14

are considerably higher than turnover rates in low-minority schools (19.9% versus 10.8%). Special

education teachers in high-minority schools are also 3.5 times more likely to be alternatively

certied than special education teachers in low-minority schools (24.7% versus 6.9%).

Special education teachers are more likely to state that they left teaching due to retirement or for

nancial reasons, compared to average leaver reports (Table 1).

Turnover in Schools Serving Historically Underserved Students

Research has long found that schools with larger

low-income and student-of-color populations

experience greater rates of teacher turnover

than schools on average.

28

Thus, in schools

serving predominantly low-income students and

students of color, students are often subjected to

a “revolving door” of less-experienced teachers.

29

Previous research suggests many conditions

contribute to these high turnover rates. Among

them, schools with primarily low-income

students and students of color are staffed by newer teachers and teachers with less preparation,

report having inferior teaching supports and working conditions, and are more deeply impacted by

accountability measures.

30

Many of these factors have previously been found to inuence teacher attrition. For example, teachers

who lack comprehensive preparation are 2 to 3 times more likely to leave teaching in their early years

than those who are fully prepared.

31

Similarly, teachers who receive less mentoring and induction

support are more likely to leave,

32

as are those who experience less desirable working conditions.

33

Schools serving vulnerable populations have the additional responsibility of responding to

community concerns, such as food insecurity, environmental pollution, and access to adequate

health care and housing. While improving teacher turnover rates may not be wholly sufcient to

address every one of these needs, increasing student access to high-quality teachers by reducing

teacher turnover is a critical effort.

Title I schools

Title I schools are those with high percentages of low-income students that receive federal funds

under Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act to help students meet academic

standards. The turnover rate in Title I schools is nearly 50% greater than that in non-Title I schools

(16% versus 11%) (see Figure 9). Mathematics and science teacher turnover rates are nearly 70%

greater in Title I schools than in non-Title I schools, and alternative certication teacher turnover is

more than 80% higher. While turnover rates for teachers with 3 or fewer years of experience are high

for teachers in all schools (with no statistically signicant difference between those in Title I and

non-Title 1 schools), teachers with more experience have turnover rates nearly 80% higher in Title I

schools than in non-Title I schools.

In schools with predominantly

low-income students and students

of color, students are often

subjected to a “revolving door” of

less-experienced teachers.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 15

Teachers in Title I schools have spent about 2

years less at their current school and have a year

less of overall teaching experience than teachers

in non-Title I schools (see Figures 10 and 11).

In most of the major subject areas, teachers in

Title I schools have spent about 2 years fewer

at their current school than those teachers in

non-Title I schools. Teachers certied through

a regular pathway have the greatest longevity

at their current Title I school (9 years), while

alternatively certied teachers spend the least

time (6 years) teaching at their current Title I

school (see Figure 10).

Teachers in Title I schools have

spent about 2 years less at their

current school and had a year less

of overall teaching experience

than teachers in non-Title I

schools.

Figure 9

0%

5%

10%

15% 20% 25% 30%

All teachers***

Humanities teachers***

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers

ELD teachers

Regular certification pathway***

Alternative certification pathway***

4 or more years experience***

3 or fewer years of experience

Teacher Turnover Is Greater in Title I Schools

11%

16%

10%

16%

18%

16%

17%

16%

20%

11%

16%

11%

28%

22%

20%

9%

16%

11%

Note: Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12 and

Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2012–13.

TURNOVER RATE

■ Non Title I Schools ■ Title I Schools

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 16

Figure 10

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

All teachers***

Humanities teachers***

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers***

Alternative certification**

Regular certification***

Teachers in Title I Schools Stay Fewer Years

10

8

11

8

8

9

7

7

6

11

9

10

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12.

YEARS AT CURRENT SCHOOL

■ Non-Title I School ■ Title I School

For the most part, differences in years of teaching experience are slight between teachers in Title I

schools and non-Title I schools. Mathematics and science teachers, however, have 2 fewer years of

experience in Title 1 schools.

Figure 11

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16

All teachers***

Humanities teachers***

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers

Alternative certification pathway**

Regular certification pathway**

Teachers in Title I Schools Have Fewer Years of Experience

14

13

15

14

12

13

12

10

8

15

14

14

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12.

YEARS OF EXPERIENCE

■ Non-Title I Schools ■ Title I Schools

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 17

Figure 12

Compared to the average teacher, teachers in schools serving students of color and students

in poverty were more likely to report that, in their decision to leave teaching, testing and

accountability measures and administrative support were very important reasons. They were less

likely to state that retirement and nancial reasons were as important.

Schools serving students of color

In the quartile of schools with the most students of color (more than 55%), the turnover rate is

about 70% greater than that in the quartile of schools with the fewest students of color (less than

10%). Across the board, turnover rates in high-minority schools are higher—regardless of teachers’

subject taught, years of experience, or certication pathway (see Figure 12). Mathematics and

science teacher turnover rates are 90% higher in the top quartile of schools than in the bottom.

Special education teachers are more than 80% more likely to turn over, and teachers certied via

an alternative pathway are 150% more likely to leave in schools with the greatest concentration

of students of color than in those with the lowest. English language development teachers and

teachers with 3 or fewer years of experience have high turnover rates in both high-minority and

low-minority schools. Nearly one in four inexperienced teachers leave high-minority schools in a

given year.

0%

5%

10% 15% 20% 25% 30%

All teachers***

Humanities teachers

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers**

ELD teachers

Regular certification pathway***

Alternative certification pathway***

4 or more years’ experience***

3 or fewer years’ experience

Teacher Turnover Is Greater When Schools Serve Primarily Students of Color

17%

10%

16%

12%

10%

20%

11%

21%

22%

16%

10%

20%

24%

18%

8%

16%

9%

19%

Note: Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12 and

Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2012–13.

TURNOVER RATE

■ Top Quartile Students of Color (55% or Greater)

■ Bottom Quartile Students of Color (Fewer Than 10%)

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 18

Consistent with the literature, teachers in high-

minority schools tend to have less experience

overall and, according to our analysis, have spent

less time teaching at their current school. In

schools with predominantly White students, the

average teacher has been teaching at the same

school for 11 years and has 15 years of teaching

experience. At schools with predominantly

students of color enrolled, the average teacher

has been teaching at the same school for 8 years

and has about 12 years of experience (see Figures 13 and 14). This differential is even greater for

mathematics and science teachers who have been at their current school for 4 years fewer if they are

in the top quartile of schools serving students of color (see Figure 13).

Figure 13

0

2 4 6

8 10 12

All teachers***

Regular certification pathway***

Alternative certification pathway***

Humanities teachers***

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers***

Teachers in Schools Serving Primarily Students of Color

Stay Fewer Years

8

11

8

11

8

8

11

7

11

7

9

6

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12.

YEARS AT CURRENT SCHOOL

■ Top Quartile Students of Color (55% or Greater)

■ Bottom Quartile Students of Color (Fewer Than 10%)

Of all teachers, those certified

through a regular pathway average

the greatest amount of teaching

experience overall, as well as at

their current placement.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 19

Figure 14

0 2 4 6

8 10 12 14 16

All teachers***

Regular certification pathway***

Alternative certification pathway***

Humanities teachers***

Mathematics and science teachers***

Special education teachers

Teachers in Schools Serving Primarily Students of Color Have Less

Overall Experience

13

15

14

15

10

13

15

11

15

12

13

9

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12.

YEARS OF EXPERIENCE

■ Top Quartile Students of Color (55% or greater)

■ Bottom Quartile Students of Color (Fewer Than 10%)

Of all teachers, those certied through a regular pathway average the greatest amount of

teaching experience overall and time at their current placement, whether at schools with

predominantly students of color or with predominantly White students, while alternatively

certied teachers average the least amount of teaching experience and fewest years teaching in

their current placement. Alternatively certied teachers spend about 3 years fewer at schools

with predominantly students of color than regularly certied teachers and have 5 fewer years of

experience overall. More than half of all alternative certication teachers teach in schools with

the greatest concentrations of students of color and account for 21% of teachers in these schools.

In contrast, alternative certication teachers account for less than 9% of teachers in schools with

predominantly White students. Thus, schools with predominantly students of color are most

likely to have teachers with the fewest years of teaching experience, the fewest years at their

school site, and the highest turnover rates at their schools.

Controlling for all other variables, teachers at schools with the greatest proportion of students

of color move schools or leave teaching at a rate 50% higher than teachers in schools with the

fewest students of color (p < 0.05). However, as other studies show, the predictive relationship

between student race and teacher turnover is reduced when working conditions are included as

well, suggesting that these conditions explain at least some of the high rates of teacher turnover in

high-minority schools.

34

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 20

Turnover of Teachers of Color

Students of color comprised 49% of public

school students nationally in 2012 and are

projected to be in the majority by the year 2024.

Teachers of color made up just 18% of the public

school teacher workforce in 2012. Although

that proportion has been steadily growing,

the numbers are still much smaller than the

demand from employers and families.

35

Previous

research demonstrates that teacher diversity

has several important outcomes for students of

color: Teachers of color appear to improve the

schooling experiences and academic outcomes

of students of color, and they are more likely to

feel called to teaching positions in low-income

communities of color where openings are difcult to ll.

36

Several studies also suggest that all

students benet from having teachers of color because they bring distinctive knowledge and

experiences, and function as role models to the student body as a whole.

37

Despite successful recruitment of teachers of color in recent years, high turnover rates continue to

contribute to shortages of teachers of color.

38

A key step to increasing the proportion of teachers of

color in the teacher workforce is addressing the particular factors that contribute to their decisions

to move schools and leave teaching.

With 3 in 4 teachers of color working in the quarter of schools with the most students of color, their

turnover decisions have important implications, especially for students of color, who have been

found to perform better in school when they have teachers of color.

39

While the overall teacher

mover rate has remained fairly steady, that is not so for teachers of color, who have experienced a

mover rate that has ranged from 6% to 10% since 1988. Teachers of color and White teachers have

left the workforce at similar rates over time (see Figure 15) but have moved schools at signicantly

different rates (see Figure 16).

Teachers of color are also more likely to enter teaching through an alternative pathway.

A quarter of teachers of color did so, double the share for White teachers. While there is a

statistically signicant difference in the overall turnover rates of teachers of color and White

teachers (18.9% and 15.1%, respectively), this does not hold true across school types. When

teachers of color and White teachers work in schools with the same proportion of students of color,

their turnover rates are statistically indistinguishable. This analysis shows that teachers of color are

simply more likely to teach in schools where turnover rates are higher for all teachers.

Teachers of color appear to

improve the schooling experiences

and academic outcomes of

students of color, and they are

more likely to feel called to

teaching positions in low-income

communities of color where

openings are difficult to fill.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 21

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center

for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey,

2011–12 and Teacher Follow-up Survey, 2012–13.

Teacher Leaving Rates,

1988–89 to 2012–13

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

■ Teachers of Color ■ White Teachers

YEARS

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center

for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey,

2011–12 and Teacher Follow-up Survey, 2012–13.

Teacher Moving Rates,

1988–89 to 2012–13

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

■ Teachers of Color ■ White Teachers

YEARS

Figure 15 Figure 16

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 22

Teachers overall

Black teachers

Non-Black teachers

0%

5% 10% 15% 20% 25%

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 2011–12

and Teacher Follow-Up Survey, 2012–13.

Teacher Leaver and Mover Rates, 2012

TURNOVER RATE

■ Leavers Rate ■ Movers Rate

8.1%

11.7%

7.8 %

7.7%

10.1%

7.5 %

Figure 17

The Special Case of Black Teacher Turnover

Historically, Black teachers have played a central role in American schools. Being largely responsible

for the education of Black children from Reconstruction to the era of school integration—about 100

years—Black teachers have been community leaders and have helped to build the Black middle

class.

40

In more recent years, Black teachers have comprised a perpetually small share of the teacher

workforce. While the Black teacher workforce has grown from 191,000 teachers in 1987–88 to

231,000 in 2011–12, the proportion of Black teachers decreased from 8.2% to 6.8% of the teacher

workforce during the same period. Meanwhile, Black students comprised nearly 16% of the public

school student population in 2013.

Across a range of studies, Black teachers have been associated with lower dropout rates, improved

student achievement, increased student interest in college, and positive perceptions from students.

41

Additionally, Black teachers are more likely to feel called to teaching in low-income communities

of color where openings are difficult to fill. Nearly 80% of Black teachers work in schools in the top

quartile of students of color, and more than 70% teach in Title I schools.

Although Black teachers were once more likely to stay in teaching than White teachers, Black teacher

turnover rates are now extremely high. At about 22%, the Black teacher turnover rate is nearly 50%

greater than the non-Black teacher turnover rate (see Figure 17). In the South, where Black teachers

are most likely to teach, their annual turnover rates are 26%.

Considering the important role Black teachers play in the workforce and their diminishing position in it,

it is essential to identify ways to reduce their attrition from the workforce.

Reasons for Black teacher turnover

Black teachers have about the same average age and teaching experience as other teachers, but Black

teachers in their first year in 2012 were 3.5 times more likely to have no student teaching experience

than all other first-year teachers (28.2% versus 7.9%), a discrepancy driven by disproportionate entry

through alternative certification routes. Nearly half of newly hired Black teachers were certified through

an alternative pathway, compared to just 22% of all other first-year teachers.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 23

In 2012, in an era of school closings and layoffs in many cities, the rate of involuntary turnover was

much higher for Black teachers than for all other teachers, constituting nearly a third of all turnover.

Twelve percent of Black teachers who left the profession did so involuntarily, while 10% of teachers

on average did.

42

While about 30% of all movers left their schools involuntarily,

43

over 50% of Black

teachers moved involuntarily.

This has been substantially a function of teacher layoffs during the recession and school closings

in urban districts due both to declining enrollments and sanctions targeted to schools with low

test scores under No Child Left Behind.

44

Decreases in the numbers of Black teachers have been

proportionally much greater than decreases in the size of the overall teaching force in some of the

nation’s largest cities, listed in Table 2. In New Orleans, more than 7,000 teachers—most of whom were

Black—were fired en masse after Hurricane Katrina. They were replaced by predominantly young, White

teachers brought in to teach in the charter schools that replaced the district schools. As a result, the

number of Black teachers declined there by more than 62%. In other major cities, the number of Black

teachers has declined by anywhere from 15% to 39%.

Table 2

Change in Proportion of Teachers in Selected Cities by Teacher Race,

2000–12

City Overall White Black Hispanic

Boston -3.3 -0.8 -18.3 1.1

Chicago -13.4 -3.2 -39.2 6.4

Cleveland -17.4 -12.0 -33.9 -9.4

Los Angeles -16.9 -28.0 -33.2 6.5

New Orleans -44.4 3.3 -62.3 43.5

New York City -2.0 -1.9 -15.1 2.4

San Francisco -11.9 -21.9 -32.4 8.1

Source: Albert Shanker Institute

Among voluntary leavers, Black teachers in 2012–13 were much less likely to say they left for personal

or family reasons, or to find a school in a more convenient location, and much more likely to express

dissatisfaction with their salary, lack of resources, worries about job security due to accountability

measures, lack of classroom autonomy, and lack of collegial support. Nearly twice as many Black

teachers as non-Black teachers strongly disagreed that the materials they need to teach were readily

available to them (e.g., textbooks, supplies, copy machines, etc.).

There is hope to be found in the fact that Black teachers tended to cite specific issues with respect to

their teaching conditions as reasons for leaving. These can be addressed by policy interventions, which

can be a tool for increasing Black teacher retention.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | TEACHER TURNOVER: WHY IT MATTERS AND WHAT WE CAN DO ABOUT IT 24

Predictors of Turnover

The descriptive data presented above illustrate patterns of attrition; however, they do not control

for various inuences that might be associated with these trends. There are a number of factors

that have been found to impact teachers’ decisions to stay in their classrooms, move schools, or

leave teaching altogether, including compensation, student characteristics, teacher preparation and

mentoring, age and experience, and working conditions.

In order to learn how each of these contribute to decisions to move or leave, we calculated teachers’

predicted probabilities of leaving their school from a logistic regression model that controls, rst,

for a variety of school characteristics, then for teacher characteristics, main teaching subject area,

and, nally, workplace conditions (see Technical Appendix, page 35).

School Characteristics

Some previous research has suggested that

teachers have a preference for teaching in

schools with wealthier, higher-performing, and

greater proportions of White students.

45

Other

research, however, emphasizes the desire of

many teachers to work with vulnerable student

populations and illustrates how a host of factors,

including teacher preparation and workplace

conditions, make that difcult to sustain.

46

Consistent with previous research, we found

that, controlling for school size and student

poverty rates, those teaching in schools with

25% or more students of color were more likely to move or leave teaching than teachers in schools

with fewer students of color, all else being equal (see Figure 18). Student characteristics, such

as eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch, were not signicantly related to turnover, but it is

of interest to note that they became somewhat less predictive of teacher turnover when other

variables, such as working conditions, were also included in the model. We recognize that there may

be other unobserved variables, such as working conditions that are not accounted for in our model,