Research Summary

c c s r

CONSORTIUM ON

CHICAGO SCHOOL RESEARCH

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

URBAN EDUCATION INSTITUTE

September 2011

Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three

Eras of Reform: Summary of Key Findings

Stuart Luppescu, Elaine M. Allensworth, Paul Moore, Marisa de la Torre, James Murphy

with Sanja Jagesic

1

2

3

This report was the result of a group effort by many people, and we greatly appreciate

the support and feedback we received from our colleagues at the Consortium on Chicago

School Research (CCSR) and the CCSR Steering Committee. Special thanks to Holly

Hart for researching and constructing the Reform Timeline and working on the early

stages of this study. Several CCSR directors provided feedback on early drafts of this

report, including Penny Sebring, Paul Goren, David Stevens, Jenny Nagaoka, Melissa

Roderick, and Sue Sporte. We appreciate their efforts greatly. We are also very grateful

for the considerable help of CCSR Associate Director for Communications, Emily Krone,

who provided tireless editing and substantive feedback. We are also very grateful for the

support of our Steering Committee and the members who took the time to read drafts

of this report and provide us with valuable feedback. We particularly thank Kim Zalent,

Arie van der Ploeg, Kathleen St. Louis, Steve Zemelman, Matt Stagner, Josie Yanguas,

and Greg Michie.

We would like to thank the Illinois State Board of Education for providing test data and

Chicago Public Schools (CPS) for their continued cooperation and support in providing us

with data that allow us to do this work.

Most importantly, we want to acknowledge the Chicago Community Trust for taking

the initiative to commission this study and providing the funding to carry it out.

Acknowledgements

2

Chapter

1

consortium on chicago school research at the university of chicago

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ............................................................................. 1

Summary of Key Findings ...................................................................5

Problems with Publicly Reported Statistics ..................................................6

Reading and Math Test Scores in Grades Three through Eight ......................8

High School Test Scores ...........................................................................12

Graduation and Dropout Rates ...............................................................14

Conclusion ................................................................................................17

Endnotes ...................................................................................................21

This is a summary of key findings from a more comprehensive study. The full report is

available at ccsr.uchicago.edu.

2

consortium on chicago school research at the university of chicago

1

Executive Summary

I

n 1988, U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett proclaimed Chicago’s

public schools to be the worst in the nation. Since that time, Chicago has

been at the forefront of urban school reform. Beginning with a dramatic

move in 1990 to shift power away from the central office, through CEO

Paul Vallas’s use of standardized testing to hold schools and students

accountable for teaching and learning, and into CEO Arne Duncan’s bold

plan to create 100 new schools in 10 years, Chicago has attempted to boost

academic achievement through a succession of innovative policies. Each

wave of reform has brought new practices, programs, and policies that have

interacted with the initiatives of the preceding wave. And with each succes-

sive wave of reform this fundamental question has been raised: Has progress

been made at Chicago Public Schools (CPS)?

This study addresses the question by analyzing trends in elementary

and high school test scores and graduation rates over the past 20 years. Key

findings described briefly in this summary report include:

• Graduation rates have improved dramatically, and high school test scores have

risen; more students are graduating without a decline in average academic

performance.

• Math scores have improved incrementally in the elementary/middle grades,

while elementary/middle grade reading scores have remained fairly flat for

two decades.

• Racial gaps in achievement have steadily increased, with White students

making more progress than Latino students, and African American students

falling behind all other groups.

• Despite progress, the vast majority of CPS students are at academic achieve-

ment levels that are far below what they need to graduate ready for college.

2 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

Many of the findings in this report contradict trends

that appear in publicly reported data. For instance,

publicly reported statistics indicate that CPS has made

tremendous progress in elementary math and reading

tests, while this analysis demonstrates only incremental

gains in math and almost no growth in reading. The

discrepancies are due to myriad issues with publicly

reported data—including changes in test content and

scoring—that make year-over-year comparisons nearly

impossible without complex statistical analyses, such as

those undertaken for this report. This leads to another

key message in this report:

•

The publicly reported statistics used to hold schools

and districts accountable for making academic

progress are not accurate measures of progress.

For this study, we addressed the problems in the

public statistics by carefully constructing measures

and methods to make valid year-over-year compari-

sons. This allowed us to create an accurate account of

the progress made by CPS since the early 1990s. The

Consortium on Chicago School Research (CCSR) at

the University of Chicago has a long history of tracking

trends in Chicago’s schools. Through 20 years of study-

ing the district, we have developed methods for using

student data to create indicators that are comparable

over time, adjusting for changes in tests, policies, and

conditions that make the publicly reported statistics

unsuitable for gauging trends in student performance.

We divide the last 20 years into three eras of reform,

defined by district leadership and the central reform

policies that those leaders pursued. Era 1 is the time of

decentralized control of schools, when decisions over

budget and staffing were transferred from the central

office to locally elected school boards. Era 2 is defined

by the beginning of mayoral control over the schools,

the tenure of Paul Vallas as CEO, and the beginning

of strong accountability measures for students and

schools. Era 3 is defined by Arne Duncan’s tenure as

CEO, the emphasis on diversification through the

creation of new schools, and a greater use of data in

practice. While these three eras are defined by very

different key policies, each era of reform builds on the

reforms of the previous era.

This report shows areas of substantial progress, as well

as areas of concern, and counters a number of miscon-

ceptions that exist about the state of the schools. What it

does not do is draw conclusions about the effects of par-

ticular school policies on the progress of students. Changes

in student achievement over the last 20 years are a result

of the totality of policies, programs, and demographic

changes that have occurred in and around the schools.

The policies of each new school administration have in-

teracted with the policies of the preceding administration.

In some cases over the past 20 years, individual policies

have been studied; where evidence exists that a policy had a

specific effect on student outcomes, we report it. However,

it is beyond the scope of this study to definitively analyze

the combined effects of myriad policies.

Graduation Rates Have Improved Dramatically,

Without a Decline in High School Performance

Chicago schools have shown remarkable progress over

the last 20 years in high school graduation rates. In the

early 1990s, students who entered Chicago high schools

were equally likely to drop out as to graduate. Now they

are more than twice as likely to graduate as to drop

out. Graduation rates have improved among students

of all racial/ethnic groups and among both boys and

girls. Improvements in graduation rates began to occur

in Era 1, slowed down in Era 2, and then accelerated

considerably in Era 3.

At the same time, high school students have improved

their performance on the tests administered to all high

school juniors in Illinois, with ACT scores rising by

about a point over the last decade. All students who

graduate now do so with courses required for admission

to college, while many students used to take just one

science credit and remedial math and English courses.

Math Scores Have Improved Incrementally in the

Elementary/Middle Grades, but Reading Scores

Have Remained Fairly Flat

Math scores have risen in the elementary/middle

grades; students are now scoring at a level similar to

students who were one year older in the early 1990s,

at least in some grade levels. This could be viewed as a

remarkable improvement; at the same time, the typical

student has moved from just meeting state standards

Executive Summary

3

to a level that is still at the low end of the range of

scores that meet state standards. Students at this level

are extremely unlikely to reach ACT college-readiness

benchmarks by the time they are juniors in high school.

Due to a disconnect between the elementary school

ISAT standards and the high school college-readiness

standards as defined by ACT, elementary students

must actually exceed standards—rather than simply

meet standards—on the Illinois test in order to have a

reasonable chance of meeting ACT college benchmarks

in high school.

Reading scores in the elementary/middle grades

have not shown much improvement over the three

eras of school reform. There were some improvements

in the lower grades during Era 2, and scores improved

modestly among White and Asian students across all

three eras. However, scores have not improved at all

among African American students, which is the largest

racial group in CPS. Reading skills in general remain

at a low level.

While students’ test performance is low in Chicago,

it is not lower than the test performance at other schools

in Illinois that serve similar populations of students.

In fact, Chicago students score better than residents

of other parts of Illinois who attend schools that serve

students with similar backgrounds. However, because

Chicago schools serve a very economically disadvan-

taged student population compared to most of the rest

of Illinois, their performance is much lower than the

average school in Illinois.

The Average Student Is Far Below College-Ready

Standards

Most CPS students meet state learning standards on

the state tests in the elementary/middle grades. How-

ever, the eighth grade state standards are well below

the ninth grade benchmarks for college readiness. Few

CPS students meet these benchmarks when they enter

high school, which means they have little chance of

making enough progress to attain ACT scores that are

expected for admission to four-year colleges. Previous

CCSR research has shown that the elementary state

standards are far easier to meet than the high school

standards, making it appear that students are better

prepared for high school than they actually are.

Racial Gaps Increased in All Eras, Especially the Gap

Between African American Students and Students of

Other Races/Ethnicities

College readiness among African American and Latino

students is an area of particular concern. By 2009, White

and Asian CPS students had average ACT scores that

were close to ACT college-readiness benchmarks. They

were also likely to have taken the high school courses

that would be expected of applicants to selective four-year

colleges. However, the elementary and high school test

scores of African American and Latino students were

much further behind. Furthermore, African American

students’ scores improved the least over the three eras.

Especially in the elementary/middle schools, test scores

for African American students improved at a much

slower rate than those of other students. Average scores

for African American students improved slightly in

math, while improving moderately among other stu-

dents. There were virtually no improvements in reading

scores among African American students, while White

and Asian students showed some modest improvements

and Latino students showed some slight improvements.

Thus, African American students increasingly fell behind

other students over the last 20 years, especially in Era 3.

Even in an Age of Accountability, Publicly Reported

Statistics Are Not Useful for Gauging District Progress

Chicago not only has been at the forefront of school

reform policies but has also been ahead of most of the

rest of the country in collecting data and tracking stu-

dent and school performance. Yet, even with a heavy

emphasis on data use and accountability indicators, the

publicly reported statistics that are used by CPS and

other school districts to gauge progress are simply not

useful for measuring trends over time. The indicators

have changed frequently—due to policies at the local,

state, and federal levels; changes made by test makers;

and changes in the types and numbers of students in-

cluded in the statistics. As there is a greater push at both

the state and federal levels to use data to judge student

and school progress, we must ensure that the statistics

that are used are comparable over time. Otherwise,

future decisions about school reform will be based on

flawed statistics and a poor understanding of where

progress has been made.

4 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

2

consortium on chicago school research at the university of chicago

5

Summary of Key Findings

C

hicago school reform from 1990 to 2009 can be divided into three eras,

based on district leadership and key policies. Most of the reforms from

one era continued into subsequent eras, making it difficult to attribute the

effects of any policy to a particular CPS administration. Era 1 begins with

the passage of the Chicago School Reform Act of 1988. This act established

Local School Councils, which were composed of the school principal, repre-

sentatives of the faculty, parents, and community members. This act devolved

authority to the local schools that had previously been held by the central

office. The Local School Councils had the power to hire the principal, as well

as to allocate financial resources and to make decisions about curriculum and

other academic matters. We refer to this era as “Decentralization.”

In 1995, the state gave the mayor of Chicago authority over the city

schools. Mayor Richard M. Daley installed his former budget director, Paul

Vallas, in a newly created position: CEO. The Vallas administration brought

stability in district leadership and union negotiations, as well as infrastructure

improvement to the city’s schools. The new administration also enacted tough

policies that were designed to improve student achievement. New graduation

requirements required all students to take a college preparatory curriculum.

Performance standards were enacted for both students and schools based

on standardized test scores, with severe consequences for not meeting the

expectations. Beginning in 1996, students in eighth grade were required to

earn a minimum score on the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills (ITBS) to enroll in

high school. In the next year, students in grades three and six had similar

promotional requirements. This resulted in 7,000 to 10,000 students retained

in grade per year. In addition, schools with large proportions of low-scoring

students were put on probation, subjected to intervention, and, in extreme

cases, reconstituted. Because of the emphasis on testing and test performance,

In this document, we

highlight findings from

a larger report that is

available at ccsr.uchicago.

edu. Here we provide a

quick overview of some key

trends across the system,

which are discussed in

more detail in the larger

report. The larger report

includes additional ways of

looking at trends in student

performance, as well as

information on statistical

methodology. It also

provides information

on some key aspects

of school climate and

organization that are not

included here, particularly

changes in the quality of

school safety, instruction,

professional capacity, and

leadership over time.

6 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

we refer to this era as “Accountability.” When Paul

Vallas resigned in 2001 he was replaced by his deputy

chief-of-staff, Arne Duncan.

The Duncan administration was characterized

by opening many new charter and contract schools,

focusing on transforming high schools, closing poorly

performing schools, instituting new instructional

programs, and working to improve professional

development. One of the hallmark policies of the

Duncan administration was Renaissance 2010, the

plan to open 100 new schools in 10 years. From 2001

to 2009, Chicago saw 155 new schools open and 82

schools close.

The Duncan administration initiated major efforts

to improve the use of data at schools, developing

mechanisms to provide high schools with timely data

reports on students’ progress in ninth grade and college

outcomes. The Duncan administration pursued various

strategies to increase coherency in curriculum, intensify

professional development efforts, and raise awareness

about the importance of literacy and math through

various initiatives. The era was marked by the creation

and reorganization of central offices around curricular

areas and the provision of math and literacy coaches

to support their efforts.

During the Duncan administration, the federal

government initiated school-level accountability at

the national level through the No Child Left Behind

Act. Because this period featured so many different

approaches to educational reform, including a large

expansion of the number and types of schools in the

system, we call the period of the Duncan administra-

tion “Diversification.” In 2009, Arne Duncan left CPS

to become the U.S. Secretary of Education.

Problems with Publicly Reported Statistics

There is an abundance of student- and school-level

data designed to provide the public with an account of

what is taking place in CPS and in other school

districts across the nation. While these data are useful

for answering some questions, the publicly reported

statistics are not always appropriate for measuring

trends over time. This is a critical issue to address

because there are increasing calls to use data to make

decisions about schools and because substantial

resources are being used to develop new data systems.

The data presented in this report have been adjusted

to address these issues, so that comparisons over

time can be made fairly. To learn more about how

we accounted for issues with the comparability of the

statistics, see Chapter 2 in the full report.

The following is a sampling of the problems that had

to be resolved in order to compare indicators over time:

•

Changes in tests, standards, scoring methods, and

test administration make publicly reported test

scores non-comparable. A number of changes in

tests and testing procedures have occurred since

1990 (see Figure 1), making it difficult to know

if changes in test scores are due to changes in real

learning or a result of changes in the tests.

•

CPS reports the percentage of students who scored

at a certain benchmark in a given year; for example,

the percentage of students who met state standards

in reading or math. Benchmark scores are imprecise

metrics that are not useful for measuring change

over time. This is because change in the statistic

depends more on how many students have scores

that are close to the cut-off point than on how much

growth in learning actually occurs. If many students

have scores close to the cut-off, even small changes

in test scores can show large swings in the percent-

age of students meeting the benchmarks. Similarly,

if few students are close to the cut-off point, large

changes in test scores may barely affect the percent-

age of students meeting the benchmarks. The use

of benchmark scores, rather than average scores,

has led to incorrect assessments of the progress made

in CPS over the last 15 years.

•

The introduction of grade promotion standards in

1996 affected the movement of students through the

elementary/middle grades. Therefore, the composi-

tion of students in particular grades changed dra-

matically. The policy caused many more low-scoring

students to spend extra time in grades three, six, and

eight, while reducing the number of low-scoring

students in grades four and seven in some years.

It also led to the lowest-scoring students spending

Summary of Key Findings

7

2

more time in elementary/middle school so they

were counted in CPS statistics on test performance

for extra years. For example, the lowest-scoring third-

graders in 1997 would be counted in third grade

averages in both 1997 and 1998 because they did not

move on to fourth grade. They would also be included

in CPS statistics for seven years instead of six years,

which would lower district performance levels.

• Not all students’ test scores are counted in district

averages in each year. Because of changes in local

and federal policies, there were declines and then

increases in the proportion of CPS students with

reported test scores (see Figure 2). Prior to 2008,

students’ test scores could be excluded from public

reporting depending on their bilingual or special

education status. Students who transfer schools

mid-year also may not be included in the reported

statistics. At the lowest point, only 74 percent of

students had their scores reported in school or

district averages. Variations in test score reporting

rates affect the test score trends because students

excluded from reporting tend to have lower scores,

on average, than other students.

• The population of students served by CPS changed

over time, gradually becoming more Latino (see

Figure 3). Changes in the types of students attending

CPS could affect test score trends, even if Chicago

schools do no better or worse at educating students,

because historically there are differences in student

achievement by race/ethnicity.

More information about the issues encountered in publicly

reported statistics and the methods we used for addressing

these problems are available in the full report. The full report

also provides further information about inconsistencies in

ISAT scoring.

Figure 1. Numerous changes in the tests make the statistics available to the public non-comparable over time and not useful

for gauging academic progress

Percent of Students at / above Norms (ITBS)

80

60

70

90

50

Publicly Reported Reading Test Scores for Grades Three through Eight

199219911990 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

ITBS (Percent of Students at / above Norms) ISAT(Percent of Students Meeting / Exceeding State Standards)

40

100

20

10

0

30

80

60

70

90

50

40

100

20

10

0

30

Percent of Students Meeting / Exceeding State Standards (ISAT)

22.3

43.7

59.1

64.9

Change in Scoring

(retroactive)

Change in

Test Content

Change in Standards and

Test Administration

Procedures

Change in Test:

Content, Timing,

Scoring Inconsistent

FIG URE 1

Changes in the tests make the statistics available to the public non-comparable over time

and not useful for gauging academic progress

8 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

Reading and Math Test Scores in

Grades Three through Eight

Across the three eras, elementary/middle school math

scores in CPS increased on the standardized tests

taken by all third- through eighth-graders in Illinois,

while reading scores inched up slightly. However,

Figure 2. Prior to the Federal No Child Left Behind Act, Many Students’ Test Scores Were Not Included in Publicly Reported Statistics

ITBS

Percent of Students Reported

80

60

70

100

90

50

30

10

20

40

0

Percentage of Students with Test Scores Included in Publicly Reported Statistics

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

85%

ISAT

84%

81%

80%

80%

78% 78%

74%

75% 74%

74%

75%

76% 76%

83% 83%

93%

94%

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

FIG URE 2

Prior to the federal No Child Left Behind Act, many students’ test scores were not included in

publicly reported statistics, making statistics reported to the public non-comparable over time

Figure 3. The percentage of Latino students in the district has increased across the three eras, while the percentage of

African American students decreased

Percent of Students Reported

80

60

70

100

90

50

30

10

20

40

0

Racial/Ethnic Composition of CPS Students in Grades Three through Eight

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

57%

28%

12%

56%

29%

12%

55%

30%

12%

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

54%

31%

12%

53%

32%

12%

53%

32%

12%

53%

32%

11%

53%

33%

11%

52%

34%

11%

52%

34%

10%

52%

35%

52%

36%

9%10%

51%

37%

9%

50%

38%

9%

49%

39%

9%

48%

47%

41%

9%

40%

9%

46%

42%

9%

African American Latino White Asian

FIG URE 3

The percentage of Latino students has increased across the three eras,

while the percentage of African American students decreased

despite real improvements in math scores and slight

improvements in reading scores, the vast majority of

CPS students remain so far behind when they enter

high school that it is nearly impossible for them to

meet standards on the Prairie State Achievement Exam

(PSAE), the statewide test for juniors that includes

Summary of Key Findings

9

the ACT. These findings, which use statistics that

can be compared fairly over time, show trends that are

very different from the trends in the publicly reported

statistics (such as those shown in Figure 1, on page 7).

In addition, while elementary/middle math and

reading scores improved on average, some groups of stu-

dents improved much less than others. In every era, the

performance gap between African American students

and students of other races/ethnicities widened.

READING test scores rose during Era 2 in the lower

grades, but they were flat during the other eras (see

Figure 4). While it looks as if reading scores rose at the

end of Era 3, our analysis of the 2008 and 2009 tests

suggest that this trend resulted from inconsistencies in

the way that the statewide test for elementary school

students was scored during those years rather than

actual improvements in reading skills among CPS stu-

dents. Indeed, the statewide average and the Chicago

average improved at the same rate in 2008 and 2009,

providing further evidence that the improvement was

likely a result of scoring issues with the statewide test.

Reading scores in Chicago were also flat on the national

exam, the National Assessment of Educational Progress

(NAEP), during the period that students in Chicago

took the ISAT.

MATH scores rose in the middle of Era 1, but they fell

at the end of the era (see Figure 5). In Era 2 they rose

so much that students at some ages had the same aver-

age scores as students one year older at the beginning

of Era 1. Math scores were flat at the beginning of

Era 3, but they showed improvements at the end of the era.

In contrast to reading scores, math scores in Chicago

improved slightly more than math scores statewide at

the end of Era 3, suggesting that part of these gains re-

sulted from real skill improvements among CPS students.

The gains in Era 2, coupled with modest improve-

ment in Era 3, might seem to constitute major progress.

However, as shown in Figure 6, the end result is that the

average student moved from just below meeting state

standards to a level that is still in the bottom half of the

Reading Scores (ISAT Units)

260

240

250

270

230

210

200

190

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

220

Average Reading Test Scores for Nine to 14-Year-Olds across the Three Eras

Figure 4. Reading scores increased during Era 2, but not in other eras

199219911990 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Age 9 Age 10 Age 11 Age 12 Age 13 Age 14

ITBS ISAT

Note: Data from 1990 to 2005 are ITBS rescaled to the ISAT scale. Data records are not

sufficiently accurate at the older ages in the first two years of the study to include in the

figure. The trend lines are broken between 2005 and 2006 to indicate the change in tests that

were given to students. Students took the ITBS prior to 2006 and the ISAT beginning in

2006. Scores are adjusted for changes in race, gender, and socio-economic level; and for

changes in test type, form, and level.

FIG URE 4

Reading scores increased during Era 2, but not in other eras

10 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

Figure 5. Math scores were up in all eras, especially in Era 2

Math Scores (ISAT Units)

260

240

250

270

230

210

200

190

Average Math Test Scores for Nine through 14-Year-Olds across the Three Eras

199219911990 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Note: Data from 1990 to 2005 are ITBS rescaled to the ISAT scale. Data records are not

sufficiently accurate at the older ages in the first two years of the study to include in the

figure. The trend lines are broken between 2005 and 2006 to indicate the change in tests that

were given to students. Students took the ITBS prior to 2006 and the ISAT beginning in

2006. Scores are adjusted for changes in race, gender, and socio-economic level; and for

changes in test type, form, and level.

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

Age 9 Age 10 Age 11 Age 12 Age 13 Age 14

220

ITBS ISAT

FIG URE 5

Math scores were up in all eras, especially in Era 2

Math Test Scores for 14-Year-Olds

Figure 6. Test scores improved all along the range of scores, not just at the top or bottom

90%

75%

50%

25%

10%

Exceeds

288–

Meets

246–287

Below

221–245

Note: This figure shows the overall distribution of math scores for students in one age group:

14-year-olds. ITBS national percentile ranks and ISAT performance levels are indicated on

the vertical axis. The dashed white lines indicate the ITBS national percentile ranks; the ISAT

performance levels are shown by the background shading. The boxes show the distribution

of math scores by 14-year-olds. The horizontal bar in the middle of the box indicates the

median (50th percentile point); the top and bottom of each box are the 75th percentile and

25th percentile, respectively. The top and bottom of the “whiskers” extending from each box

indicate the 90th and 10th percentile, respectively. Note that the percentiles given by the

boxes pertain to 14-year-olds in CPS, not to national percentiles.

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

2004

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

ITBS (National Percentile)

ISAT

ITBS ISAT

FIG URE 6

Math test scores improved all along the range of scores, not just at the top or bottom

Summary of Key Findings

11

Figure 7. Reading test scores were mostly flat and did not improve among African American students

Reading Scores (ISAT Units)

250

230

240

270

260

220

200

Reading Test Scores in Elementary/Middle Grades by Racial/Ethnic Group

199219911990 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

210

African American Latino White Asian

ITBS ISAT

Note: The decline in scores in 2006 is a result of the change in tests and the lack of familiarity

with the new test format, as described in the full report. Trends from 2006 through 2009 could

not be adjusted for changes in ISAT scoring and do not seem to reflect real changes in skills. See

the full report for more details.

FIG URE 7

Reading test scores did not improve among African American students; they improved slightly for other groups

“meets standards” category. This is a problem because

the state sets a very low bar for meeting standards in

elementary/middle school. In fact, eighth grade stu-

dents at the very top of the “meets” category have only

about a 60 percent chance of getting a 20 or above on

the ACT three years subsequent.

1

Meanwhile, only

about one-quarter to one-third of students in the low/

middle region of the “meets” category reach the 20

point mark on the ACT three years later. Thus, the

typical CPS eighth-grader will need to show extraor-

dinary learning gains in high school to have test scores

expected for college by the time he or she graduates.

• Reading and math scores grew more for Asian, White,

and Latino students than for African American students.

• Reading scores improved slightly among all

racial/ethnic groups, except African American

students (see Figure 7). The average reading

score for African Americans in 2009 was very

close to the average score in 1990.

• Math scores rose considerably among Asian,

White, and Latino students but modestly among

African American students (see Figure 8).

• While Latino and African American students

had the same average math and reading scores

in 1990, Latino students’ scores were signifi-

cantly higher than African American students’

scores by 2009.

• The widening of the gap in reading and math

scores between White and African American

elementary grade students in Chicago was

larger than seen in national trends. On the

national NAEP exam, fourth grade racial gaps

closed substantially over the course of the three

eras in both reading and math, while eighth

grade gaps were not consistently up or down.

2

• Math and reading scores also increased more

among White and Asian students than among

Latino students.

12 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

• In Eras 1 and 3, schools that started off with the low-

est levels of achievement—those that most needed

to improve—were the least likely to show substantial

improvements in either reading or math. Integrated

schools, in which at least 30 percent of the students

were White or Asian, were the most likely to show

improving test scores in all eras, especially in Era 3.

High School Test Scores

Since 2001, eleventh-graders in Illinois high schools have

been required to take the ACT as part of the Prairie State

Achievement Exam each spring. In general, ACT scores

in CPS have been improving. However, average scores

are still far below levels that would make students eligible

for admission at most four-year colleges.

During Era 3, the percentage of CPS freshmen who

took the ACT within three years of entering high school

increased considerably, from 58 percent of students

entering in fall 2000 to 69 percent of students entering

in 2006. More students were making it through the first

three years of high school to take the ACT on time;

fewer students had dropped out or failed to make

expected grade progression. At the same time, ACT

scores increased by a full point between 2001 and 2009,

from an average of 16.2 to 17.2 (see Figure 9).

Improvements in ACT scores occurred despite no im-

provements in the achievement level of students entering

CPS high schools. The EXPLORE scores from tests that

students take as they enter high school did not improve,

while the ACT scores rose (see Figure 9).

Despite this steady increase, the average score re-

mains far below college-readiness benchmarks. ACT

has established a benchmark college-readiness score

of 21 for the composite score; students scoring at this

level have a fifty-fifty chance of getting at least a B in

entry-level college classes, according to the ACT. White

and Asian students in CPS have average scores that are

about at this level, but the scores of Latino and African

American students are substantially below the bench-

mark scores. The full report provides more information

about ACT scores and college-readiness levels.

3

As with the elementary/middle school scores, high

school test scores did not improve uniformly across all

racial/ethnic groups.

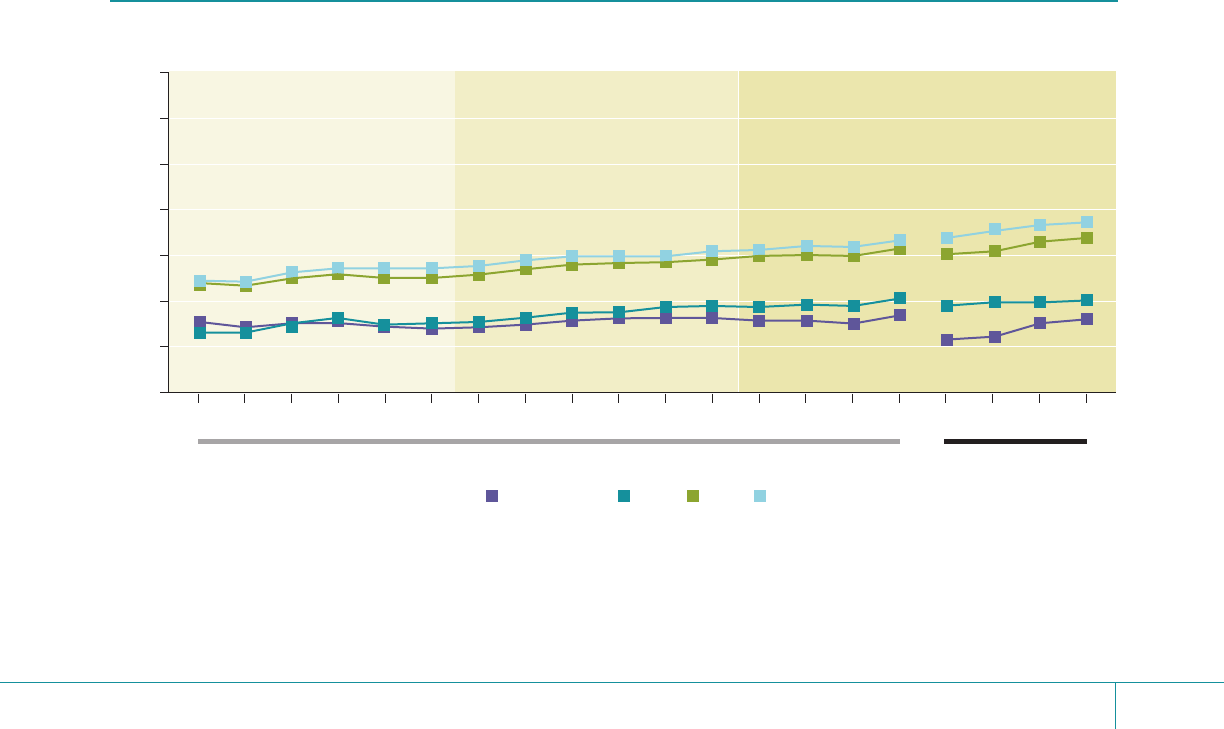

Figure 8. While math test scores of all students rose, improvements were smallest among African American students

Math Scores (ISAT Units)

Math Test Scores in Elementary/Middle Grades by Racial/Ethnic Group

199219911990 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

ITBS ISAT

250

260

270

240

220

210

200

230

African American Latino White Asian

Note: The decline in scores in 2006 is a result of the change in tests and the lack of familiarity

with the new test format, as described in the full report. Trends from 2006 through 2009 could

not be adjusted for changes in ISAT scoring and exaggerate real changes in skills. See the full

report for more details.

FIG URE 8

While math test scores of all students rose, improvements were smallest among African American students

Summary of Key Findings

13

Figure 9. Eleventh grade ACT scores have been rising, even though entering ninth grade ACT scores have been flat

Mean Composite Score

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

2007 2008 2009

Era 2

Students

Eras 2 and 3

Students

Era 3

Students

ACT Year (Spring)

Adjusted ACT

Unadjusted ACT

EXPLORE Year (Fall)

Unadjusted EXPLORE

18

16

17

20

19

15

13

14

16.2

16.2

16.3

16.4

16.4

16.5

16.6

16.9

16.8

17.1

16.8

17.1

17.1

17.3

17.3

17.3

17.1

17.2

14.2

14.1 14.1

14.0 14.0

Note: Adjusted ACT scores control for changes in student body composition, compared to

2001, in terms of students’ race, gender, and socio-economic level. EXPLORE is taken in

October of the ninth grade year and can be used as a measure of students’ academic skills

as they begin high school. The average EXPLORE score for the ninth grade cohort that is

displayed corresponds with on-time test-taking for the ACT year. For example, if a student

was taking the ACT on time (i.e., in their third year) in 2005, they would have taken EXPLORE

in fall 2002. The EXPLORE value then is the average ninth grade EXPLORE score for all the

students who were first-time freshmen in 2002. Similar trends are observed if we only include

the EXPLORE scores for students who made it to the end of the eleventh grade to take the

ACT, although the averages are somewhat higher.

ACT Scores and EXPLORE Scores, 2001–2009

Unadjusted ACT Adjusted ACT Unadjusted EXPLORE

FIG URE 9

Eleventh grade ACT scores have been rising, even though entering ninth grade EXPLORE scores have been flat

FIG URE 10

ACT scores improved among students of all races/ethnicities

Figure 10. ACT scores improved among students of all races/ethnicities

ACT Composite Score

ACT Scores by Student Race/Ethnicity

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Era 1 Era 2 Era 3

19

20

21

22

18

16

15

14

17

African American Latino White Asian

Note: ACT scores by race/ethnicity are adjusted for entering achievement, gender, and neighborhood poverty and social status.

18.7

19.4

18.8

19.4

18.9

19.5

19.0

19.7

19.2

20.0

19.1

19.9

19.5

20.2

20.0

21.0

19.8

20.7

15.0

15.6

15.1

15.7

15.2

15.7

15.4

15.8

15.6

16.1

15.6

16.1

15.9

16.2

16.0

16.6

15.9

16.5

14 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

• While scores grew for students of all races/ethnici-

ties, the scores of White and Asian students increased

more than those of African American or Latino

students (see Figure 10).

• Scores grew in all types of schools during Era 3,

but the largest improvements occurred in selective

enrollment high schools, and racially integrated

schools (those where at least 30 percent of students

are White or Asian).

Graduation and Dropout Rates

A sustained improvement in graduation rates and a

concurrent decline in dropout rates constitute the

most striking and positive findings of this report.

Chicago’s graduation rates increased substantially

over the course of the three eras. CPS students who

were 13 years old in the fall of 1991 were about as

likely to drop out by age 18 as they were to graduate. In

many high schools, dropout rates were higher than

graduation rates. Fourteen years later, CPS students

who were 13 years old in 2005 were more than twice

as likely to graduate by age 18 than to drop out.

Two-thirds of CPS students now obtain regular CPS

diplomas by age 19, compared with less than half of

students at the beginning of Era 1.

4

Graduation rates are usually reported for groups of

students based on the year they enter high school, and

such rates are available in the larger report. However,

these rates are problematic for examining trends over

time, as they can fluctuate with changes in grade

promotion policies (e.g., delaying when students enter

ninth grade), creation of new schools with irregular

grade structures (e.g., middle schools with grade nine),

and changes in the percentage of students who drop

out prior to ninth grade. For these reasons, we present

graduation rates by age group—following students

from age 13 until age 19. These rates are more inclu-

sive and are not affected by irregular grade progression

among students or grade structure among schools.

FIG URE 11

Graduation rates improved dramatically, especially during Era 3

Graduation and Dropout Rates for Cohorts of 13-Year-Olds Followed until Age 19

Figure 11. Graduation rates have improved dramatically, especially during Era 3

Percent of Students

Eras 1 and 2 Eras 2 and 3 Era 3

50

30

40

70

60

20

0

10

41.1

48.0

37.6

53.4

66.1

20.8

Graduation Age 18 Dropout Age 18 Graduation Age 19

Note: This figure tracks graduation and dropout rates for cohorts of students from age 13

until ages 18 and 19. Points from different lines at the same point on the horizontal axis show

outcomes for students from the same cohort, but at different ages. Graduation rates are

computed by tracking students over multiple years; therefore, they may have been 13 years

old in one era and 19 years old in another era. These statistics include students who

transferred into CPS after age 13 and incorporate them into the corresponding age cohort.

Students who left CPS through a school transfer, institutionalization, or death are not

included in the calculation of the statistics.

19921991 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Age 13

Fall of

Age 18

19971996 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010Fall of

Age 19

19981997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010Fall of

Summary of Key Findings

15

Graduation Rates by Race/Ethnicity for Male Students

Figure 12. Graduation rates improved for male students of all races/ethnicities, but remain low for boys

Percent of Students

Eras 1 and 2 Eras 2 and 3 Era 3

50

30

40

70

60

80

100

90

20

0

10

35.0

48.9

72.5

44.1

85.1

73.1

64.3

50.2

African American, Graduation Age 19 Latino, Graduation Age 19 White, Graduation Age 19 Asian, Graduation Age 19

19921991 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Age 13

Fall of

Age 19

19981997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010Fall of

FIG URE 12

Graduation rates have improved dramatically, but remain low for boys

• Students who were 13 years old in 1991 were more

likely to drop out than to graduate by age 18, as

shown in Figure 11 (41 percent versus 38 percent).

By comparison, among students who were 13 in

2005, the last group of students with data through

age 18, 20.8 percent had dropped out by age 18 and

53.4 percent had graduated by the age of 18.

• Less than half of the 1991 cohort had graduated

by the time they were 19 in 1997. In contrast, 66

percent of the 2004 cohort of 13 year olds graduated

by the time they were 19 in 2010.

• Graduation rates for girls were substantially higher

than for boys, among students of all races/ethnicities

(see Figures 12 and 13). However, both boys and

girls showed substantial improvements in graduation

rates over the three eras.

• Graduation rates for African American students

are the lowest and grew the least of all racial/ethnic

groups. However, graduation rates still improved

considerably. Among students who were 19 years

old in 2010, half of African American boys and

nearly 70 percent of African American girls gradu-

ated. In 1997, by comparison, 35 percent of African

American boys and 53 percent of African American

girls graduated by age 19.

16 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

Graduation Rates by Race/Ethnicity for Female Students

Figure 13. Girls graduated at much higher rates than boys

Percent of Students

Eras 1 and 2 Eras 2 and 3 Era 3

50

30

40

70

60

80

100

90

20

0

10

52.6

63.0

79.2

55.8

89.5

82.8

75.5

69.6

African American, Graduation Age 19 Latino, Graduation Age 19 White, Graduation Age 19 Asian, Graduation Age 19

19921991 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Age 13

Fall of

Age 19

19981997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010Fall of

FIG URE 13

Girls graduated at much higher rates than boys in all racial/ethnic groups

2

consortium on chicago school research at the university of chicago

17

Conclusion

Interpretive Summary and

Areas for Further Study

C

hicago schools are not what they were in 1990. Graduation rates have

improved tremendously, and students are more academically prepared

than they were two decades ago. ACT scores have risen in recent years, and

elementary math scores are almost a grade level above where they were in

the early 1990s. However, average elementary school test scores remain well

below levels necessary for doing college preparatory work in high school. High

schools have little chance of preparing students for college when they enter

ninth grade with extremely low skill levels. In fact, despite some improvements

in test gains in the high schools, average high school test scores remain well

below levels that indicate students are likely to succeed in college. This is not

a problem that is unique to Chicago. Nationwide, the typical high school

graduate also fails to perform at college-ready levels. Students with similar

economic and ethnic backgrounds at other schools in Illinois actually tend

to perform worse than Chicago students. However, the district has a long

way to go before the average student graduates ready to succeed in college.

Era 1, the era of decentralization when schools were given the latitude

to formulate and execute their own improvement strategies, was a baseline

period for this study. Our data sources begin to provide good information

in the middle of the era; thus, it is difficult to gauge the extent to which

students’ achievement improved under decentralization. However, there were

at least modest improvements in both elementary and high schools during

Era 1. Graduation rates were very low, but improving. And math scores rose

in the elementary grades, although they flattened in the end of the era.

18 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

Other research at CCSR has documented the uneven-

ness in school improvement under decentralization;

during decentralization the schools serving students

from the most economically disadvantaged commu-

nities were least likely to improve, while the schools

serving more advantaged communities were most

likely to improve.

5

These outcomes can be explained

by differences in the social resources available in

school communities. Because decentralization placed

power in the hands of elected Local School Councils,

it is not surprising that communities where residents

were active in local organizations and where schools

faced fewer social problems were more likely to show

improvements.

Era 2 was an era of strict test-based accountability

measures and bold initiatives that were enacted to trans-

form high schools (e.g., changing graduation require-

ments so that all students took a college preparatory cur-

riculum). There were large investments in infrastructure

and stability in district leadership. Test scores in the

elementary/middle grades rose during this period, and

they improved in schools serving students of all types of

backgrounds. This was the only era to show large im-

provements in the lowest-achieving schools. Prior CCSR

studies have found that the test-based accountability

policies, which held schools accountable for improve-

ments in test scores and required students to pass tests

to be promoted from certain grades, had mixed results

for students.

6

They encouraged teachers and parents to

provide more support to the lowest-achieving students,

and they encouraged better alignment of instruction to

grade-level standards. At the same time, they resulted in

a narrowing of the curriculum to focus on tested subjects

(reading and math), more instructional time spent on

test-taking practice, and a large increase in grade reten-

tion in the elementary schools. Test-based promotion

policies resulted in more students entering high school

who were old for their grade level; this had a depressing

effect on graduation rates.

7

In fact, the improvements in

graduation rates that had been occurring in Era 1 were

set back in Era 2. This dip occurred, in part, because of

the increase in grade retention and also because of the

change in graduation requirements that ended remedial

coursework and required all high school students to take

a college preparatory curriculum.

8

In Era 3, there were large improvements in outcomes

in the high schools and very little improvement in the

elementary schools. Improvements that had been oc-

curring in graduation rates accelerated, and were seen

in all types of schools, among boys and girls and all

racial/ethnic groups. At the same time, scores on the

ACT rose, even though students were not entering high

school better prepared. Students were learning more

while in high school. In the elementary grades, test

scores dropped—especially in the lowest-performing

schools. Equity declined, so that schools serving

African American students, and those that started out

the era with the lowest levels of performance, were less

likely than more advantaged schools to have improving

test scores.

While the effects of the dominant policies of Eras 1

and 2 are largely understood, much research remains

to be done to understand both the positive and prob-

lematic effects of the policies in Era 3. The decline in

equity, with African American students falling further

behind students from other racial/ethnic groups, is

particularly disturbing and has raised questions about

policies that disproportionately affected African

American students (e.g., the decision to close chroni-

cally low-performing schools and send students to other

schools). One CCSR study showed no improvements

in test scores for students who were displaced by school

closings,

9

but there is yet to be an analysis of the over-

all effect of the policies on all students and schools.

Another area requiring more study is the rise in student

performance in the high schools. Era 3 brought a much

greater use of data in the high schools to track students

and provide targeted support for passing classes and

college readiness. Further research should investigate

whether this use of data led to the improved outcomes

and, if so, exactly how it happened.

The findings in this report contradict common percep-

tions about district performance over the last two decades.

It has been widely believed that elementary schools have

improved considerably, while high schools have stagnated.

In fact, the opposite is true. These misperceptions arise

because of problems with the metrics that are used to

judge school performance, and differences in the stan-

dards by which high schools and elementary schools are

held accountable. High schools are increasingly being

Conclusion

19

judged by college-ready standards, particularly by college-

ready benchmark scores on the ACT. The benchmark

score on the ACT-aligned EXPLORE exam that students

take at the beginning of high school corresponds to much

higher skill levels than the “meets standards” benchmark

on the spring eighth grade ISAT exam. Thus, it appears

that high schools are less successful when, in fact, they

are simply held to a much higher standard. This problem

is accentuated by focusing on benchmark scores rather

than averages—few students are close to meeting the high

school benchmarks on the ACT, so it looks like there

has been little movement when there has been growth.

A further reason for misperceptions about elementary

school performance comes from non-equivalent tests,

scoring, and test administration procedures over time.

These changes have often led scores to look like they

are improving when, in fact, skill levels have remained

the same.

This report raises important questions about how

much improvement we can reasonably expect in a large

system over the span of two decades. A number of

dramatic system-wide initiatives were enacted over the

course of the three eras of school reform. But instead of

catalyzing dramatic changes in student achievement,

district-wide changes were incremental—when they

occurred at all. Meanwhile, throughout the three eras,

individual schools did manage to make substantial

improvements. Past research at CCSR suggests that

the process of school improvement involves careful

attention to building the core organizational supports

of schools—leadership, professional capacity, parent/

community involvement, school learning climate,

and instruction.

10

In fact, schools that are strong in at

least three of these five areas are 10 times more likely

to improve than schools that are weak. Building the

organizational capacity of schools takes time and is not

easily mandated at the district level. Nevertheless, the

extent to which the next era of school reform drives

system-wide improvement will likely depend on the

extent to which the next generation of reforms attends

to local context and the capacity of individual schools

throughout the district.

2

consortium on chicago school research at the university of chicago

21

Endnotes

Summary of Key Findings

1. Easton, J.Q., S. Ponisciak, and S. Luppescu (2008). From high

school to the future: The pathway to 20. Chicago: Consortium on

Chicago School Research.

2.

Analysis based on publicly available NAEP data. Department

of Education. Institute of Education Sciences. National Center

for Education Statistics (11/05/2002). “National Assessment

of Educational Progress (NAEP) Data Files.” (http://hdl.

handle.net/1902.5/609759) National Archives and Records

Administration.

3.

Also see: Roderick, M., J. Nagaoka, and E.M. Allensworth (2006).

From high school to the future: A first look at Chicago Public School

graduates’ college enrollment, college preparation, and graduation from

four-year colleges. Allensworth, E.M., M. Correa, and S. Ponisciak

(2008). From high school to the future: ACT preparation—too much,

too late.

4. Our calculations only include students who enter CPS through

regular (non-alternative) schools. Students who leave a regular

school and enter an alternative school are counted as dropouts.

Students who never enrolled in a regular CPS school are not

included in the calculations.

Conclusion

5. Bryk, A.S., P. Bender Sebring, E.M. Allensworth, S. Luppescu,

and J.Q. Easton (2010). Organizing schools for improvement:

Lessons from Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

6.

Roderick, M., and J. Nagaoka (2005). Retention under Chicago’s

high-stakes testing program: Helpful, harmful, or harmless?

Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(4), 309–40;

Allensworth, E.M., and J. Nagaoka (2010). “The effects of

retaining students in grade with high stakes promotion tests.”

Chapter 20 in J. Meece (ed.), Handbook on Schools, Schooling,

and Human Development, Taylor and Francis.

7.

Allensworth, E.M. (2005). Dropout rates after high-stakes testing

in elementary school: A study of the contradictory effects of

Chicago’s efforts to end social promotion. Educational Evaluation

and Policy Analysis, 27(4).

8.

Montgomery, N., and E.M. Allensworth (2010). Passing through

science: The effects of raising graduation requirements in science

on course-taking and academic achievement in Chicago. Chicago:

Consortium on Chicago School Research.

9.

De la Torre, M., and J. Gwynne (2009). When schools close:

Effects on displaced students in Chicago Public Schools. Chicago:

Consortium on Chicago School Research.

10. Bryk, A.S., P. Bender Sebring, E.M. Allensworth, S. Luppescu,

and J.Q. Easton (2010). Organizing schools for improvement:

Lessons from Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

About the Authors

Stuart Luppescu

Stuart Luppescu is CCSR’s Chief Psychometrician, specializing in educational measurement. He received B.A.

and M.A. degrees in Linguistics from Cornell, an M.A. in English as a Second Language from the University of

Hawaii, and a Ph.D. in Educational Measurement from the University of Chicago. Before coming to Chicago,

Mr. Luppescu taught English in Japan and Hawaii for 13 years. His research interests are in language acquisition,

Rasch Measurement, and multi-level modeling of achievement data.

Elaine M. Allensworth

Elaine Allensworth, Ph.D., is Senior Director and Chief Research Officer at the Consortium on Chicago School

Research at the University of Chicago. She is best known for her research on early indicators of high school

graduation, college readiness, and the transition from middle to high school. Her work on early indicators of

high school graduation has been adopted for tracking systems used in Chicago and other districts across the

country, and is the basis for a tool developed by the National High School Center. She is one of the authors of the

book Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago, which provides a detailed analysis of school

practices and community conditions that promote school improvement. Currently, she is working on several studies

of high school curriculum funded by the Institute of Education Sciences at the U.S. Department of Education

and the National Science Foundation. She recently began a study of middle grade predictors of college readiness,

funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Dr. Allensworth holds a Ph.D. in Sociology, an M.A. in Urban

Studies from Michigan State University, and was once a high school Spanish and science teacher.

Paul Moore

Paul Moore is a research analyst at CCSR and is in the process of completing an M.A. in the Social Sciences

at the University of Chicago. His research interests include quantitative modeling and methodology, and he is

currently working on a study of middle grade predictors of college readiness funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates

Foundation. Paul earned a B.S. in Mathematics and Education from Vanderbilt University.

Marisa de la Torre

Marisa de la Torre is Associate Director for Professional Development at CCSR. Her work involves studying

different Chicago Public Schools’ policies, including high school choice and school closings. Her work on high

school choice in Chicago was recently published in School Choice and School Improvement. Currently, she is

studying a number of different reforms aimed at low-performing schools and indicators of high school readiness.

Before joining CCSR, she worked for the Chicago Public Schools in the Office of Research, Evaluation, and

Accountability. She received a master’s degree in Economics from Northwestern University.

James Murphy

James Murphy is a research analyst at the Consortium on Chicago School Research. He received his B.A. in

Sociology from the University of Chicago. He previously worked as an education policy analyst for the New York

City Independent Budget Office.

This report reflects the interpretation of the authors. Although CCSR’s Steering Committee provided

technical advice and reviewed earlier versions, no formal endorsement by these individuals, organizations, or the full

Consortium should be assumed.

This report was produced by CCSR’s publications and communications staff.

Editing by Ann Lindner

Graphic Design by Jeff Hall Design

Photos by David Schalliol

9-11/.5M/jh.design

T

he Consortium on Chicago School Research (CCSR) at the University of Chicago conducts research

of high technical quality that can inform and assess policy and practice in the Chicago Public Schools.

We seek to expand communication among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners as we support the

search for solutions to the problems of school reform. CCSR encourages the use of research in policy action and

improvement of practice, but does not argue for particular policies or programs. Rather, we help to build capac-

ity for school reform by identifying what matters for student success and school improvement, creating critical

indicators to chart progress, and conducting theory-driven evaluation to identify how programs and policies

are working.

Our Mission

Consortium on Chicago School Research

Steering Committee

Ruanda Garth McCullough,

Co-Chair

Loyola University, Chicago

Arie J. van der Ploeg,

Co-Chair

American Institutes

for Research

Institutional Members

Clarice Berry

Chicago Principals and

Administrators Association

Karen Lewis

Chicago Teachers Union

Individual Members

Veronica Anderson

Stanford University

Amie Greer

Vaughn Occupational

High School-CPS

Cornelia Grumman

Ounce of Prevention

Timothy Knowles

Urban Education Institute

Dennis Lacewell

Urban Prep Charter Academy

for Young Men

Lila Leff

Umoja Student Development

Corporation

Peter Martinez

University of Illinois

at Chicago

Gregory Michie

Concordia University

of Chicago

Brian Spittle

DePaul University

Matthew Stagner

Chapin Hall

Center for Children

Luis R. Soria

Ellen Mitchell

Elementary School

Kathleen St. Louis

The Chicago Public

Education Fund

Amy Treadwell

Teach Plus Chicago

Josie Yanguas

Illinois Resource Center

Kim Zalent

Business and

Professional People

for the Public Interest

Steve Zemelman

Illinois Writing Project

Directors

Paul D. Goren

Lewis-Sebring Director

Consortium on Chicago

School Research

Elaine M. Allensworth

Senior Director and

Chief Research Officer

Consortium on Chicago

School Research

Melissa Roderick

Hermon Dunlap Smith

Professor

School of Social Service

Administration

University of Chicago

Penny Bender Sebring

Founding Director

Consortium on Chicago

School Research

24 Trends in Chicago’s Schools across Three Eras of Reform

ccsr.uchicago.edu

1313 East 60th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 T 773-702-3364 F 773-702-2010

c c s r

CONSORTIUM ON

CHICAGO SCHOOL RESEARCH

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

URBAN EDUCATION INSTITUTE