How the Trump

Administration Neglected

the Neediest Small

Businesses in the PPP

UNDERSERVED

AND

UNPROTECTED

COVIDOVERSIGHT

COVIDOVERSIGHT

CORONAVIRUS.HOUSE.GOV

S E L E C T S U B C O M M I T T E E O N T H E C O R O N A V I R U S C R I S I S

S T A F F R E P O R T / O C T O B E R 2 0 2 0

This report provides preliminary findings from the Select Subcommittee’s ongoing

investigation of the implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) by the Small

Business Administration (SBA) and the Department of the Treasury (Treasury). The report finds

that contrary to Congress’s clear intent, the Trump Administration and many big banks failed to

prioritize small businesses in underserved markets, including minority and women-owned

businesses. As a result, small businesses that were truly in need of financial support during the

economic crisis often faced longer waits and more obstacles to receiving PPP funding than

larger, wealthier companies.

Congress established the PPP in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security

(CARES) Act in March 2020 to help small businesses and non-profit organizations survive the

coronavirus crisis by providing forgivable loans to cover payroll, rent, and utility payments. The

CARES Act urged SBA to issue guidance “to ensure that the processing and disbursement of

covered loans prioritizes small business concerns and entities in underserved and rural markets,”

including businesses owned by veterans, members of the military community, socially and

economically disadvantaged individuals, and women.

On June 15, 2020, the Select Subcommittee launched an investigation into the Trump

Administration’s implementation of the PPP following reports that the program favored larger

companies over the neediest small businesses.

1

The Select Subcommittee sent letters to SBA,

Treasury, two banking industry associations,

2

and eight financial institutions: JPMorgan Chase

(JPMorgan), Citibank (Citi), PNC Bank (PNC), Bank of America, U.S. Bank, Truist, Wells

Fargo, and Santander.

3

The Subcommittee obtained over 30,000 pages of documents, conducted

briefings, and interviewed community lenders and other stakeholders. The Subcommittee also

obtained detailed loan data from seven financial institutions.

The Select Subcommittee’s investigation revealed that Treasury, SBA, and several large

financial institutions failed to implement the PPP as Congress intended in at least three critical

respects:

1

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, Press Release: Select Subcommittee Launches

Investigation Into Disbursement Of PPP Funds (June 15, 2020) (online at https://coronavirus.house.gov/news/press-

releases/select-subcommittee-launches-investigation-disbursement-ppp-funds).

2

Letter from Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, to Greg Baer,

President and Chief Executive Officer, Bank Policy Institute (Sept. 10, 2020) (online at

https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/2020-09-

10.Clyburn%20to%20Baer%20re%20BPI_.pdf); Letter from Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on

the Coronavirus Crisis, to Richard Hunt, President and Chief Executive Officer, Consumer Bankers Associati

on

(Sep

t. 10, 2020) (online at https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/2020-09-

10.Clyburn%20to%20Hunt%20re%20CBA_.pdf).

3

The Select Subcommittee sent letters to the largest PPP lenders and financial institutions that were the

subject of public reporting indicating that they created a two-tier system for processing PPP loan applications.

1

1. Treasury privately encouraged banks to limit their PPP lending to existing

customers, excluding many minority and women-owned businesses.

Documents obtained by the Subcommittee show that Treasury privately told

lenders to “go to their existing customer base” when issuing PPP loans. Banks

recognized this created “a heightened risk of disparate impact on minority and

women-owned businesses,” but many banks followed Treasury’s direction. In

response to questions from Select Subcommittee staff, Treasury officials claimed

inaccurately that the Department “never addressed anything about lenders

prioritizing existing customers.”

2. SBA and Treasury failed to issue guidance prioritizing underserved markets,

including minority and women-owned businesses. SBA and Treasury did not

issue any meaningful guidance to lenders to prioritize underserved markets as

Congress urged in the CARES Act. Instead, SBA sent a vague tweet—

immediately after the Select Subcommittee launched its investigation and just two

weeks before the program expired—which lenders said had no impact on the

program.

3. Several lenders processed bigger PPP loans for wealthy customers at more

than twice the speed of smaller loans for the neediest small businesses.

Several financial institutions set up PPP lending programs in which larger

commercial clients enjoyed a separate, faster process. JPMorgan—the biggest

PPP lender—processed loans above $5 million almost four times faster than loans

under $1 million. PNC and Truist processed their largest loans at approximately

twice the speed of the smallest loans. These three lenders also processed loans to

larger companies with more than 100 employees on average 70% faster than loans

to smaller companies with 5 or fewer employees.

The Administration’s implementation failures had consequences. The Federal Reserve

Bank of New York reported, “Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black business

ownership has sharply dropped.” Forty-one percent of businesses owned by African Americans

failed between February and April 2020, higher than any other demographic group and more

than double the percentage of White-owned businesses that closed over the same period. The

New York Fed identified “racial disparities in access to federal relief funds,” including “stark

PPP coverage gaps” in hard-hit communities with many minority-owned businesses.

4

While

legislative updates to the PPP provided additional funds, targeted funds to community financial

institutions, and extended the application deadline, these improvements came too late to benefit

businesses that had already failed.

To address these problems and ensure that relief funds reach those who need them most,

this report makes several recommendations for SBA and Treasury if the PPP is extended,

including (1) issuing clear and detailed guidance to enable lenders to prioritize underserved

markets, including minority and women-owned business; (2) investing in Community

4

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth

Effects in Black Communities (Aug. 2020) (online at

www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses).

2

Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs) to

ensure they are equipped to handle the demand for PPP loans; and (3) adding a demographic

questionnaire to the PPP application form to provide transparency about disparities in this

program. However, because PPP is only available to existing small businesses, these

improvements will not benefit businesses that have already failed. For this and other reasons,

any PPP extension must be part of a broader, comprehensive response to the coronavirus crisis.

As coronavirus cases surged across the country in Spring 2020 and states began to

implement lockdowns to stem the spread of the virus, thousands of small businesses were forced

to shutter or suffered steep drops in business. Minority and women-owned businesses faced

heightened risk, in part because they are overrepresented in industries hardest hit by the

pandemic such as food services, retail, and hotels.

5

In response, Congress passed the CARES Act and established the PPP to provide a

lifeline for small businesses that otherwise might be forced to lay off employees or permanently

close. The CARES Act stated that SBA “should issue guidance to lenders and agents to ensure

that the processing and disbursement of covered loans prioritizes small business concerns and

entities in underserved and rural markets,” including businesses owned by veterans, members of

the military community, socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, and women.

6

To implement the PPP, Treasury and SBA relied on private lenders to collect borrower

application materials, review them for eligibility, and process loans. Treasury and SBA provided

the PPP loan application to lenders, but they excluded the standard demographic questionnaire

that is part of the application for SBA’s 7(a) loan program on which the PPP was modeled.

Due to high demand, the initial round of $349 billion in PPP funding was exhausted in 14

days. In April 2020, Congress expanded the program by an additional $321 billion through the

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act. Congress dedicated $60

billion of these funds for community lenders. This included CDFIs and MDIs which

traditionally serve clients in economically distressed areas who may lack relationships with

5

Businesses Owned by Women and Minorities Have Grown. Will COVID-19 Undo That?, Brookings

Institution (Apr. 14, 2020) (online at www.brookings.edu/research/businesses-owned-by-women-and-minorities-

have-grown-will-covid-19-undo-that/).

6

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), Pub. L. No. 116-136, §§ 1102, 1106

(2020).

3

traditional banks.

7

On May 28, 2020, Treasury and SBA designated an additional $10 billion

from this appropriation for CDFIs.

8

After a brief hiatus, Congress extended the program again through August 8, 2020, when

the PPP application window finally expired.

9

At that time, SBA had approved more than 5.2

million PPP loans totaling over $525 billion. CDFIs and MDIs processed approximately

221,000 loans worth $16.4 billion—accounting for 3.1% of the total loan value.

10

The New York Fed review of the PPP found “significant coverage gaps,” concluding that

the program reached “only 20% of eligible firms in states with the highest densities of Black-

owned firms,” and “in counties with the densest Black-owned business activity, coverage rates

were typically lower than 20%.”

11

A. Treasury Privately Encouraged Banks to Limit Their PPP Lending to

Existing Customers, Excluding Many Minority and Women-Owned

Businesses.

1. Treasury pushed banks to limit PPP lending to existing customers, but denied doing

so when pressed by the Select Subcommittee.

After the CARES Act was enacted on March 27, 2020, lenders began preparing to accept

PPP applications on the day the program was set to open, April 3, 2020. Unfortunately, SBA did

not issue its first Interim Final Rule governing PPP until April 2, and that guidance lacked key

information. One bank explained that the “abstractly articulated” guidance from SBA and

Treasury created confusion for lenders and prevented them from implementing the program as

7

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, Pub. L. No. 116-139, § 101 (2020); see

also Congressional Research Service, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Programs and

Policy Issues (Jan. 25, 2018) (online at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42770).

8

Small Business Administration, Press Release: SBA and Treasury Announce $10 Billion for CDFIs to

Participate in the Paycheck Protection Program (May 28, 2020) (online at www.sba.gov/article/2020/may/28/sba-

treasury-department-announce-10-billion-cdfis-participate-paycheck-protection-program).

9

An Act to Extend the Authority for Commitments for the Paycheck Protection Program, Pub. L. No 116-

147 (2020).

10

Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report (Aug. 8, 2020) (online at

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SBA-Paycheck-Protection-Program-Loan-Report-Round2.pdf).

11

Id.

4

Congress intended.

12

The Consumer Bankers Association (CBA) informed SBA and Treasury

that “one business day into the program, by SBA’s estimates, over 13 thousand applications have

been processed without the benefit of interpretive guidance.” CBA wrote, “Additional and clear

guidance providing direction to lenders in their efforts to assist small businesses as quickly as

possible would be of tremendous help.”

13

Despite the lack of clear written guidance, documents and information obtained by the

Select Subcommittee show that Treasury privately encouraged banks to limit their PPP lending

programs to existing customers, which had the impact of excluding many minority and women-

owned businesses that did not have established relationships with these banks.

In an email obtained by the Select Subcommittee dated March 28, 2020, the head of the

American Bankers Association (ABA) described to ABA’s board of directors a call with

Treasury officials on March 27, the day the CARES Act was enacted. He explained that

“Treasury would like for banks to go to their existing customer base.”

14

The American Bankers

Association represents “the entire banking industry.”

15

In a briefing for Select Subcommittee staff, JPMorgan corroborated this account,

explaining, “From early on there was an understanding from Treasury that banks were working

with existing clients.”

16

Yet when the Select Subcommittee staff asked Treasury about this “understanding,” they

denied it ever existed. Treasury told the Select Subcommittee that they “never addressed

anything about lenders prioritizing existing customers.”

17

12

Briefing by T.J. Hughes, Senior Vice President for Specialty Lending, Truist, to Staff, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020); see also Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice

President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution, PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020) (noting that “the ongoing issuance of Interim Final Rules

and informal FAQs by SBA throughout the PPP’s history has required both lenders and borrowers to modify their

processes or applications, respectively, to implement these changing requirements”).

13

Letter from Richard Hunt, President, Consumer Bankers Association, and Greg Baer, President, Bank

Policy Institute, to Willian Manger, Associate Administrator, Small Business Administration, and Michael

Faulkender, Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy, Department of the Treasury (Apr. 5, 2020) (online at

https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/CBA%20BPI%20letter%20to%20Treasur

y%20SBA%20April%205%202020_Redacted.pdf).

14

Email from Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to

JPMorgan Staff (Mar. 29, 2020), (online at

https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/HSSC_JPMC_00001386%20-

%20Redacted.pdf).

15

American Bankers Association, Membership Opportunities (online at www.aba.com/about-

us/membership/membership-opportunities).

16

Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to

Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020).

17

Briefing by Associate Administrator William Manger, Small Business Administration, and Assistant

Secretary Bimal Patel, Department of the Treasury, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 2,

2020).

5

Source: Email from Rob Nichols, CEO of the American Bankers Association, to American

Bankers Association Board of Directors (Mar. 28, 2020).

Despite Treasury’s denial, the Department’s private guidance to banks appears to have

had an impact. Seven of the eight financial institutions involved in this investigation limited

their PPP lending programs to existing customers.

18

Some imposed further limitations. PNC and

Truist permitted only existing customers with business banking accounts to apply for PPP.

19

Small business applicants with only a personal checking account—including many sole

18

Letter from Reginald Brown, WilmerHale LLP, Counsel to Bank of America, to Chairman James E.

Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 4, 2020); Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief

Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus

Crisis (July 6, 2020); Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset

Resolution, PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 24,

2020); Letter from Candida P. Wolff, Global Government Affairs, Citi, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 11, 2020); Letter from Peter Mahoney, Executive Vice President and Deputy General

Counsel, Truist, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020);

Briefing by Seth Goodall, Director of Corporate Responsibility, Santander, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (July 10, 2020); Letter from Steve Troutner, Head of Small Business, Wells Fargo, to Chairman

James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

19

Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution,

PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020); Letter

from Peter Mahoney, Executive Vice President and Deputy General Counsel, Truist, to Chairman James E. Clyburn,

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

6

proprietors and independent contractors—could not initially apply for PPP funds at those

institutions.

20

These lenders asserted that the Bank Secrecy Act’s anti-money laundering and know-

your-customer requirements also contributed to these decisions, and that permitting new

customers to submit PPP applications would have slowed down the processing of loan

applications. However, the evidence suggests this concern is overblown. In contrast to these

seven financial institutions, U.S. Bank allowed non-customers to apply for PPP loans through its

online portal starting the first day of the program.

21

Including non-customers in the program did

not hinder U.S. Bank’s ability to process PPP loans. On the contrary, the bank was able to

secure SBA approval for non-customers on average within 15.33 days of application, compared

to 16.68 days for existing customers.

22

2. Limiting PPP lending to existing customers had a “disparate impact on minority and

women-owned businesses.”

By limiting their PPP loan programs to existing customers, lenders shut out many

minority-owned businesses that did not have pre-existing business banking relationships. This is

particularly true for the smallest minority-owned firms, including “nonemployer firms” that do

not have any employees. According to the New York Fed:

[F]ewer than 1 in 4 Black-owned employer firms has a recent borrowing relationship

with a bank. This number drops to 1 in 10 among Black nonemployer firms, compared

with 1 in 4 white-owned nonemployers.

23

At least one bank acknowledged the negative effect of limiting its program to existing

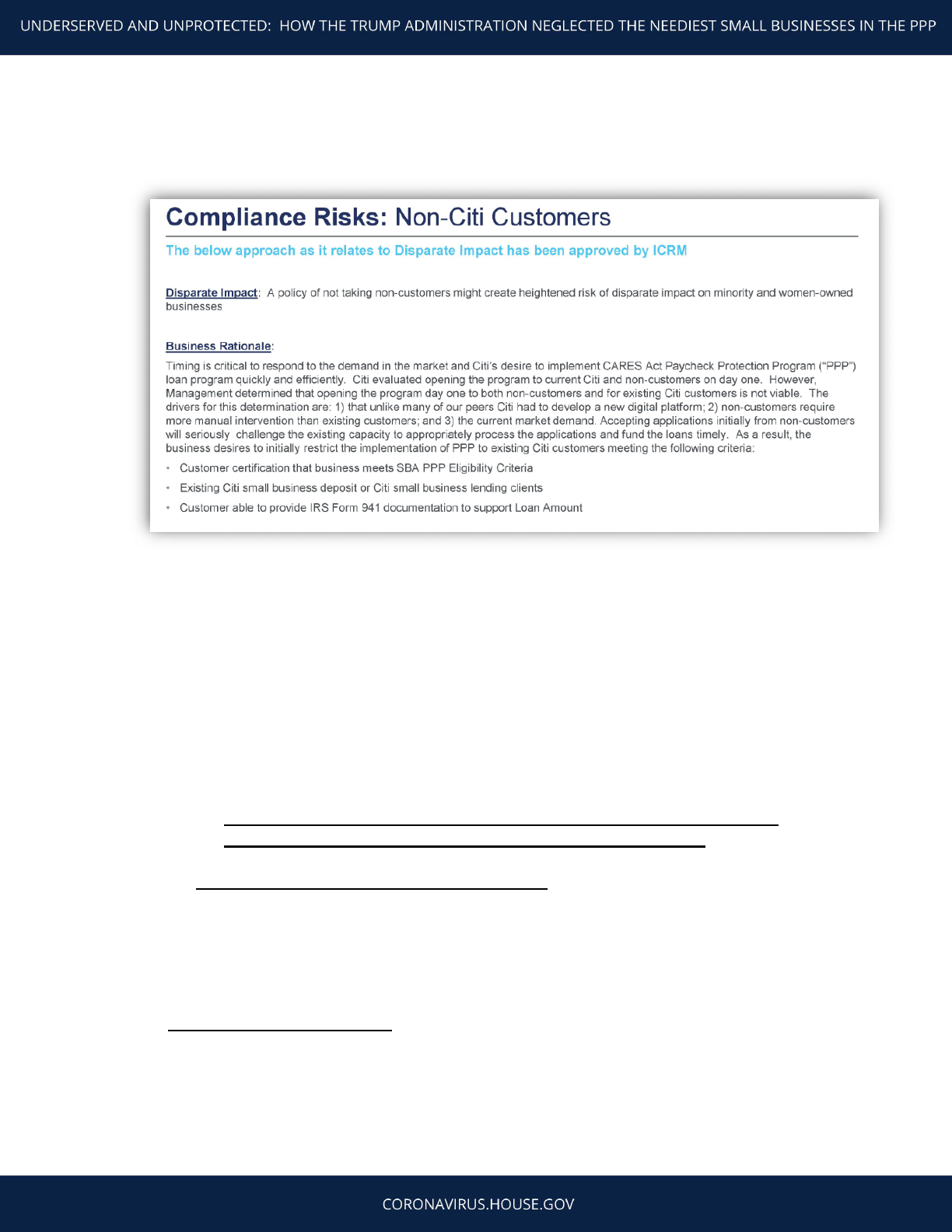

customers at the time it made the decision. The Select Subcommittee obtained an internal Citi

presentation dated April 4, 2020, which highlighted that “a policy of not taking non-customers

might create heightened risk of disparate impact on minority and women-owned businesses.”

24

The presentation was made to the bank’s Product Approval Committees, which include the

20

Truist informed Select Subcommittee staff that it later revised its procedure and enabled clients with

existing Truist retail accounts used for business purposes to apply for PPP.

21

Briefing by Lynn Heitman, Executive Vice President, U.S. Bank, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (July 1, 2020).

22

Letter from Matthew S. Miner, Morgan Lewis & Bockius LLP, Counsel to U.S. Bank, to Chairman

James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 15, 2020) (attachment describing average

time from application to funding for customers and non-customers).

23

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth

Effects in Black Communities (Aug. 2020) (online at

www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses)

(internal citations omitted).

24

Citi Presentation, CARES Act and Small Business Lending Presentation (Apr. 4, 2020) (online at

https://edit-democrats-

coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/CITI_PPP_00000014.pdf).

7

bank’s senior executives and members of the legal, compliance, finance, and operations teams.

Nonetheless, Citi proceeded to limit its lending program to existing customers.

25

Source: Internal Citi Presentation, “CARES Act and Small Business Lending,” to Citi’s Global

Product Approval Committee, North America Consumer Product Approval Committee, Global

Commercial Product Approval Committee, and North America Business Practices Committee”

(Apr. 4, 2020).

When asked by Select Subcommittee staff about the bank’s decision to limit its lending

program despite the “heightened risk of disparate impact,” Citi’s Head of U.S. Retail Banking

explained that the bank was “sensitive to the perception of disparate impact on minorities,” but

“decided that it was better to serve partners through MDIs and CDFIs.”

26

As described below,

the reliance on CDFIs and MDIs by the big banks, SBA, and Treasury failed to adequately

address the needs of minority and women-owned small businesses.

B. SBA and Treasury Failed to Issue Guidance Prioritizing Underserved

Markets, including Minority and Women-Owned Businesses

1. The Administration’s failure to issue guidance.

SBA and Treasury failed to issue adequate guidance to lenders to ensure the PPP

“prioritizes small business concerns and entities in underserved and rural markets,” as called for

by the CARES Act.

27

None of the lenders interviewed by Select Subcommittee staff recalled

receiving any formal or informal guidance from the Administration on how to service

25

Briefing by David Chubak, Head of U.S. Retail Banking, Citi, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 26, 2020).

26

Id.

27

CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 1102 (a)(2)(P)(iv) (2020).

8

underserved communities, and the documents produced to the Select Subcommittee do not

reflect such guidance.

28

JPMorgan explained that the bank “did not receive guidance from Treasury or the SBA

on prioritizing loan applications benefiting underserved and rural markets” and noted that

because “there was almost daily guidance from SBA, the bank’s expectation was that SBA or

Treasury would have issued guidance on those areas if they felt it was necessary.”

29

SBA’s

Inspector General similarly reported that it “did not find any evidence that SBA issued guidance

to lenders to prioritize the markets indicated in the Act.”

30

On June 15, 2020—the same day the Select Subcommittee launched its investigation into

the PPP and urged Treasury and SBA “to take immediate steps to ensure that remaining PPP

funds are allocated to businesses truly in need,”

31

the SBA Administrator released a tweet asking

lenders “to redouble your efforts to assist eligible borrowers in underserved and disadvantaged

communities before the upcoming #PaycheckProtection program application deadline of June

30.” This tweet was issued just two weeks before the initial expiration for the program, and long

after the first round of PPP funding had dried up. It included no guidance on how banks were

supposed to accomplish the goal of assisting underserved communities.

32

The SBA Administrator’s tweet appears to have had zero impact on their implementation

of the program. Wells Fargo explained in a briefing to Select Subcommittee staff, “anything

coming out on June 15th is late with a June 30th expiration date.”

33

None of the banks that

briefed the Subcommittee staff identified any changes to their programs in response to the

Administrator’s tweet. By the time the tweet was issued, lenders had already designed their loan

programs and processed millions of loan applications.

Banks could have done more to support women and minority businesses in their own

lending programs. Yet several banks asserted that they were hindered by the lack of guidance

from the Administration about how to prioritize underserved markets consistent with other legal

28

See, e.g., Letter from Greg D. Andres, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Counsel to JPMorgan Chase, to

Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

29

Id.

30

Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Flash Report: Small Business

Administration's Implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program Requirements (May 8, 2020) (online at

www.sba.gov/document/report-20-14-flash-report-small-business-administrations-implementation-paycheck-

protection-program-requirements).

31

Letter from Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, to Secretary

Steven Mnuchin, Department of the Treasury and Administrator Jovita Carranza, Small Business Administration

(June 15, 2020) (online at https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/2020-06-

15.Select%20Committee%20to%20Mnuchin%20Carranza-%20SBA%20re%20PPP.pdf).

32

Administrator Jovita Carranza (@SBAJovita), Small Business Administration, Twitter (June 15, 2020)

(online at https://twitter.com/SBAJovita/status/1272550003576373250).

33

Briefing by Steve Troutner, Head of Small Business, Wells Fargo, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (July 7, 2020).

9

obligations.

34

JPMorgan stated that favoring certain applicants based on the race or gender of the

business owner could implicate the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and Regulation B,

which implements ECOA.

35

According to JPMorgan, if SBA and Treasury had provided

specific guidance on how to prioritize women and minority-owned businesses, “we could do that

while balancing Reg. B and ECOA today.”

36

Bank of America similarly pointed to Regulation B

as a reason for not collecting demographic information from PPP applicants, which would have

enabled the bank to prioritize underserved markets consistent with the spirit of the CARES Act.

37

2. SBA and Treasury delayed the processing of applications from self-employed

individuals and independent contractors.

SBA and Treasury did not begin accepting PPP applications from self-employed

individuals and independent contractors until April 10, 2020—a week after the Administration

launched PPP for other types of businesses.

38

This delay is particularly concerning because SBA

issued guidance that lenders should process loans on a first-come, first-served basis,

39

and

minority-owned businesses “are far less likely to be employers,” according to SBA.

40

In fact,

approximately 96% of Black-owned businesses do not have payroll employees, as compared to

roughly 80% of all small businesses.

41

According to the Center for Responsible Lending, the Administration’s delay, “may have

caused irreparable harm to smaller businesses with no employees, which had to wait to receive

PPP funds.”

42

By April 10, 2020—when self-employed individuals and independent contractors

34

See, e.g., Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan

Chase, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020); Letter from Lakhbir Lamba,

Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution, PNC Bank, to Chairman James E.

Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

35

Letter from Greg D. Andres, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Counsel to JPMorgan Chase, to Chairman

James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

36

Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to

Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020).

37

Letter from Reginald Brown, WilmerHale LLP, Counsel to Bank of America, to Chairman James E.

Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

38

Department of the Treasury, Small Business Paycheck Protection Program (Mar. 30, 2020) (online at

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/PPP%20--%20Overview.pdf); Paycheck Protection Aid Opens for Sole

Proprietorships and Independent Contractors, CNBC (Apr. 10, 2020) (online at

www.cnbc.com/2020/04/10/paycheck-protection-program-opens-for-sole-proprietorships.html).

39

Small Business Administration, Interim Final Rule: Business Loan Program Temporary Changes;

Paycheck Protection Program (Apr. 2, 2020).

40

Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, Minority Business Ownership: Data from the 2012

Survey of Business Owners (Sept. 14, 2016) (online at https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2016/09/07141514/Minority-Owned-Businesses-in-the-US.pdf).

41

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth

Effects in Black Communities (Aug. 2020) (online at

www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses).

42

Center for Responsible Lending, The Paycheck Protection Program Continues to be Disadvantageous to

Smaller Businesses, Especially Businesses Owned by People of Color and the Self-Employed (May 27, 2020) (online

10

could begin applying for PPP—many lenders were already flooded with loan applications. PNC

informed the Select Subcommittee that by April 10, the bank “had already received tens of

thousands of applications…which meant that relatively few applications from self-employed

individuals and independent contractors could be processed and registered with the SBA before

the initial round of PPP funding was exhausted on April 16th.”

43

3. The Administration blocked community lenders from participating in the first round

of PPP, shutting out thousands of small businesses that rely on CDFIs and MDIs.

During a staff briefing on July 2, 2020, Treasury claimed that it prioritized underserved

communities by onboarding CDFIs and MDIs as lenders and setting aside funds for those

institutions to lend.

44

Many of the largest financial institutions similarly stated that they

provided financing to CDFIs and MDIs instead of prioritizing minority and women-owned small

businesses in their own lending programs.

45

Yet the Select Subcommittee’s investigation

revealed that CDFIs and MDIs were largely excluded from the first round of PPP funding and

faced several other obstacles to participating in the program.

Treasury prohibited most CDFIs and MDIs from participating in the first round of PPP

funding.

46

Specifically, Treasury required lenders to have a historical lending volume of over

$50 million to participate in PPP, shutting out many CDFIs and MDIs.

47

During the first round

of PPP, CDFIs and MDIs made just 65,000 out of 1.67 million loans.

48

at www.responsiblelending.org/sites/default/files/nodes/files/research-publication/crl-cares-act2-smallbusiness-

apr2020.pdf).

43

Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution,

PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020) (online

at

https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/PNC%20Response%20to%20House%20

Select%20Subcommittee.pdf).

44

Briefing by Associate Administrator William Manger, Small Business Administration, and Assistant

Secretary Bimal Patel, Department of the Treasury, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 2,

2020).

45

See, e.g., Briefing by T.J. Hughes, Senior Vice President for Specialty Lending, Truist, to Staff, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020); Briefing by David Chubak, Head of U.S. Retail Banking,

Citi, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 26, 2020).

46

See Letter from Chairwoman Maxine Waters, Committee on Financial Services, to Secretary Steven

Mnuchin, Department of Treasury, and Administrator Jovita Carranza, Small Business Administration (Apr. 1,

2020) (online at https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/treasury-

sba_letter_re_ppp_lender_participation_040120.pdf).

47

Small Business Administration, Interim Final Rule: Business Loan Program Temporary Changes;

Paycheck Protection Program, 85 Fed. Reg. 20811 (April 15, 2020) (online at

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-04-15/pdf/2020-07672.pdf).

48

Briefing by Associate Administrator William Manger, Small Business Administration, and Assistant

Secretary Bimal Patel, Department of the Treasury, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 2,

2020); Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report (Aug. 16, 2020) (online at

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SBA%20PPP%20Loan%20Report%20Deck.pdf).

11

Two weeks after the first round of $349 billion in funding was depleted, Treasury

lowered the lending volume threshold to $10 million, which enabled more CDFIs and MDIs to

participate.

49

Nonetheless, as one CDFI explained, “CDFIs felt like an afterthought in PPP.”

50

The U.S. Black Chambers similarly emphasized that “CDFIs struggled to be admitted into the

process.”

51

Even after SBA and Treasury lowered the lending volume threshold, many CDFIs

reported that they lacked adequate capital to issue PPP loans.

52

To help address this need, the

Federal Reserve created the Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility.

53

This program has

helped many CDFIs and MDIs, but it only became available to them on April 30, after the first

round of funding was exhausted, and after 41 percent of Black-owned businesses operating at the

start of the pandemic had already failed.

54

Many CDFIs also faced technical challenges submitting applications and providing the

technical assistance needed to help customers collect documentation and complete their

applications. One CDFI explained that even after securing access to the program, it could not

submit applications electronically until it petitioned a U.S. Senator’s office to gain access to

SBA’s electronic system.

55

Another CDFI recommended dedicated grants to cover operating

costs to CDFIs because of the additional time required to help borrowers prepare their

applications.

56

As a result of these delays and challenges, many minority and women-owned small

businesses that traditionally bank with CDFIs and MDIs faced difficulties obtaining PPP loans

during the critical early phase of the program. Overall, CDFIs and MDIs processed a total of

49

Small Business Administration, Interim Final Rule: Business Loan Program Temporary Changes;

Paycheck Protection Program – Requirements – Corporate Groups and Non-Bank and Non-Insured Depository

Institutions Lenders, 85 Fed. Reg. 26324 (May 4, 2020) (online at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/IFR--

Corporate-Groups-and-Non-Bank-and-Non-Insured-Depository-Institution-

Lenders.pdf?utm_campaign=NEWSBYTES-20200501&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua).

50

Briefing by Chief Executive Officer, Community Development Financial Institution, to Majority Staff,

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 13, 2020).

51

Briefing by U.S. Black Chambers, to Majority Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis

(Aug. 31, 2020).

52

Briefing by Executive Vice President, Community Development Financial Institution, to Majority Staff,

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 17, 2020).

53

Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Press Release: Federal Reserve Expands Access to its Paycheck

Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF) to Additional Lenders, and Expands the Collateral That Can Be

Pledged (Apr. 30, 2020) (online at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200430b.htm).

54

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth

Effects in Black Communities, (Aug. 2020) (online at

www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses).

55

Briefing by Chief Executive Officer, Community Development Financial Institution, to Majority Staff,

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 13, 2020).

56

Briefing by Executive Vice President, Community Development Financial Institution, to Majority Staff,

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 17, 2020).

12

$16.4 billion in loans—accounting for only 3.1% of the total loan value.

57

CDFIs and MDIs

would likely have had a greater impact if the Administration had allowed them to participate in

the PPP earlier and eliminated hurdles to access the program.

C. Several Financial Institutions Processed Big PPP Loans for Larger Existing

Clients at More Than Twice the Speed of Smaller Loans to the Neediest

Small Businesses.

1. Many financial institutions designed lending programs in which the largest

commercial clients benefited from a separate and faster process.

Many of the financial institutions investigated by the Select Subcommittee created a

single portal for PPP applications.

58

However, because most of these banks limited PPP lending

to existing customers, many applicants were served by the line of business that ordinarily

managed their primary banking relationship.

59

In practice, banks’ larger commercial clients,

private banking clients, and high net-worth individuals often benefitted from a faster, more

personalized experience when submitting their PPP applications.

At JPMorgan, the Wholesale Banking arm—which serves JPMorgan’s high-net worth

individuals and companies with over $20 million in revenue—provided relationship managers to

personally assist clients in completing their PPP applications.

60

By contrast, the bank’s Business

Banking arm, which processed the majority of the bank’s PPP loans, required customers to

complete the online application.

61

At Citi, three different divisions managed the bank’s PPP

loans: the Private Bank managed high-net worth individuals, its Commercial Bank served

applications for clients with $10 million or more in revenue, and its Retail Bank handled

everyone else.

62

Similarly, PNC’s Retail Bank managed the majority of its loan applications,

while its Corporate and Institutional banking arm served the bank’s largest customers and

provided relationship managers.

63

57

Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report (Aug. 8, 2020) (online at

https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SBA-Paycheck-Protection-Program-Loan-Report-Round2.pdf).

58

See, e.g., Briefing by Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset

Resolution, PNC Bank, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020); Briefing by David

Chubak, Head of Retail Banking, Citi, to Staff Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 1, 2020);

Briefing by T.J. Hughes, Senior Vice President for Specialty Lending, Truist, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020).

59

Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to

Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020); Briefing by T.J. Hughes, Senior Vice President

for Specialty Lending, Truist, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020).

60

Briefing by Jennifer Roberts, Chief Executive Officer, Business Banking Division, JPMorgan Chase, to

Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 6, 2020). JPMorgan’s Wholesale Banking group

includes the Private, Commercial, and Corporate and Investment banks.

61

Id.

62

Briefing by David Chubak, Head of Retail Banking, Citi, to Staff Select Subcommittee on the

Coronavirus Crisis (July 1, 2020).

63

Briefing by Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution,

PNC Bank, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (June 29, 2020).

13

Data produced to the Select Subcommittee reveals that the average time from application

to funding varied substantially across lines of businesses, with wealthier clients often receiving

PPP funds much more quickly than retail clients. As detailed in Table 1, JPMorgan’s Wholesale

Banking clients received PPP funding in only 3.1 days on average, whereas Business Banking

clients waited 14.9 days.

64

PNC similarly processed loans from its Corporate and Institutional

Banking clients in 15 days on average, but took 27 days to process retail banking customers.

65

Two other banks, Bank of America and Wells Fargo, also processed PPP applications by

line of business but were able to process applications without substantial timing discrepancies

across the business lines.

66

Table 1. Average Time from Application to Funding by Line of Business

Line of Business Average Days from

Application to Funding

JPMorgan

67

Wholesale Bank (customers with $20M

revenue; high net-worth individuals)

3.1

Business Bank 14.9

PNC

Corporate and Institutional Banking

(largest customers)

15.0

Retail 27.0

Source: Aggregate loan data as of July 31, 2020, from JPMorgan and PNC Bank.

68

64

Letter from Greg Andres, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Counsel to JPMorgan Chase, to Staff, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 16, 2020) (attachment).

65

Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution,

PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 24, 2020)

(attachment).

66

Letter from Reginald Brown, WilmerHale LLP, Counsel to Bank of America, to Chairman James E.

Clyburn, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 4, 2020) (attachment); Email from Julie Slocum,

Federal Government Relations, Wells Fargo, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 28,

2020) (attachment).

67

JPMorgan informed the Select Subcommittee that Business Banking loans are generally tracked as of the

day the borrower submitted an application through Business Banking’s automated portal. For the Wholesale lines of

business, loans are generally tracked as of the day the banker manually entered an application into the Wholesale

system.

68

Letter from Greg Andres, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Counsel to JPMorgan Chase, to Staff, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 16, 2020) (attachment); Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice

President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution, PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 24, 2020) (attachment).

14

2. Many banks processed higher-value loans from their largest customers much faster

than lower-value loans from smaller businesses.

Data from the largest lenders reveals that several banks also processed higher-value loans

from their largest customers at much faster rates than lower-value loans from smaller clients, as

measured by the average time from application to funding. As illustrated in Table 2:

JPMorgan processed loans above $5 million almost four times faster than loans

under $1 million. The bank processed applications from companies with over 100

employees in only 8.7 days on average but took more than 14 days to process

smaller applicants.

PNC processed loans above $5 million more than twice as fast as loans under $1

million. PNC also processed loans for businesses with more than 100 employees

at almost twice the speed of loans for smaller businesses.

Truist processed loans greater than $5 million in approximately 18 days on

average, yet took 35.5 days to process loans under $100,000. The bank processed

loans for businesses with more than 100 employees in less than 20 days, but took

over 30 days to process applicants with fewer than 100 employees.

Table 2. Average Time from Application to Funding by Size of Loan and Applicant

Average Days from Application to Funding

Loan Size JPMorgan PNC Truist

>$5M 3.7

11.0 17.9

>$1M - $5M 8.2

14.6 19.3

>$100K to $1M 14.9

22.4 23.5

$100K and Under 14.5

26.8 35.5

Applicant’s Employees

> 100

8.7 15.0 19.5

6 - 100

15.0 24.6 30.1

5 and Under

14.3 26.3 33.5

Source: Aggregate loan data as of July 31, 2020, from JPMorgan, PNC, and Truist.

69

Although some lenders, including JPMorgan, asserted to the Select Subcommittee that

they processed loans from larger customers more quickly due to the customer’s greater business

acumen, the staff’s investigation casts doubt on that explanation. U.S. Bank processed loans for

applicants with over 100 employees in 15.6 days as compared to 15.7 days for single-employee

applicants. Bank of America processed loans for both groups of applicants in roughly 22 days,

69

Letter from Greg Andres, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Counsel to JPMorgan Chase, to Staff, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 16, 2020) (attachment); Letter from Lakhbir Lamba, Executive Vice

President and Head of Retail Lending and Asset Resolution, PNC Bank, to Chairman James E. Clyburn, Select

Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Aug. 24, 2020) (attachment); Email from Casey Lucier, McGuireWoods

LLP, Counsel to Truist, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (Sept. 24, 2020) (attachment).

15

and Wells Fargo processed single-employee applicants only three days slower than its largest

applicants. Citi was the only bank that failed to produce data regarding the average time from

application to funding, asserting that it did not collect that information in the normal course of

business.

Because the Administration did not collect demographic information from PPP

applicants, the Select Subcommittee lacks hard data on how disparities in processing times

impacted minority and women-owned businesses. However, data shows that minority and

women-owned small businesses tend to be smaller than businesses with owners who are white

and male. According to the Brookings Institution, minority and women-owned businesses tend

to have 30% fewer employees compared to male or white-owned businesses.

70

As noted above,

approximately 96% of Black-owned businesses do not have any payroll employees, as compared

to roughly 80% of all small businesses.

71

This information suggests that minority and women-

owned small businesses may have faced unnecessarily long wait times for PPP loans at some

financial institutions, even if the business had a preexisting banking relationship with these

lenders.

Congress appropriated hundreds of billions of dollars for the PPP to help small

businesses and non-profit organizations survive the coronavirus crisis through the provision of

forgivable loans designed to cover payroll, rent, and utility payments. Unfortunately,

implementation of the program by the Trump Administration and many large financial

institutions deprived minority and women-owned businesses and small businesses in underserved

markets of the much-needed support that Congress intended to provide to ensure their survival.

On October 1, 2020, the House passed comprehensive coronavirus response legislation

that includes additional funding for the PPP, including targeted relief for the smallest businesses,

struggling non-profits, and the hardest hit businesses.

72

Any PPP extension must be part of a

comprehensive package, in part because the PPP can no longer assist owners and employees of

businesses that closed as a result of previous implementation failures. To prevent more closures,

Treasury and SBA should take the following actions if PPP is extended:

70

Businesses Owned by Women and Minorities Have Grown. Will COVID-19 Undo That?, Brookings

Institution (Apr. 14, 2020) (online at www.brookings.edu/research/businesses-owned-by-women-and-minorities-

have-grown-will-covid-19-undo-that/).

71

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Double Jeopardy: COVID-19’s Concentrated Health and Wealth

Effects in Black Communities (Aug. 2020) (online at

www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/DoubleJeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses).

72

House Committee on Appropriations, House Democrats’ Updated Version of the Heroes Act (online at

https://appropriations.house.gov/sites/democrats.appropriations.house.gov/files/Updated%20Heroes%20Act%20Su

mmary.pdf); H.R. 8406.

16

A. SBA and Treasury Should Issue Clear, Detailed Guidance to Enable Lenders

to Prioritize Underserved Markets, Including Minority and Women-Owned

Businesses.

SBA and Treasury should heed Congress’s recommendation and the concerns raised by

lenders by issuing clear guidance that would instruct financial institutions to prioritize

underserved markets, including minority and women-owned businesses, in a manner consistent

with fair lending laws. Congress’s decision to reserve some PPP funds for community lenders

does not relieve the Administration of its responsibility to ensure that all PPP lenders prioritize

underserved communities.

B. The Administration Should Invest in CDFIs and MDIs to Ensure They Are

Fully Equipped to Handle the Demand for PPP Loans.

If Congress extends the PPP, SBA and Treasury should consult with participating CDFIs

and MDIs to ensure that those institutions are fully equipped to handle the expected volume of

additional loan applications. The Administration should also ensure that CDFIs and MDIs have

adequate support—including funding for technical assistance—to handle applications.

To ensure CDFIs and MDIs have the resources they need to support another round of

PPP loans, the updated Heroes Act passed by the House would set aside 25% of funds, up to $15

billion, for distribution by community lenders, including CDFIs, MDIs, and microlenders.

73

C. SBA and Treasury Should Include a Demographic Questionnaire on the PPP

Application.

SBA and Treasury decided not to include a demographic questionnaire on the PPP loan

application, even though the application was modelled on the similar SBA 7(a) loan application,

which includes the demographic questionnaire.

74

Instead, the Administration opted to include

this optional questionnaire as part of the PPP loan forgiveness process, which only began in late

September 2020.

75

Treasury informed Select Subcommittee staff that the decision to omit the

demographic questionnaire from the application was “driven by speed and simplicity.”

76

Unfortunately, the Administration’s decision to only capture demographic information at

the loan forgiveness stage makes it impossible to determine conclusively the extent to which

73

Id.

74

See Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Flash Report: Small Business

Administration's Implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program Requirements (May 8, 2020) (online at

www.sba.gov/document/report-20-14-flash-report-small-business-administrations-implementation-paycheck-

protection-program-requirements).

75

Committee on Small Business, Hearing on Paycheck Protection Program: An Examination of Loan

Forgiveness, SBA Legacy Systems, and Inaccurate Data (Sept. 24, 2020) (online at

https://smallbusiness.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=3431).

76

Briefing by Associate Administrator William Manger, Small Business Administration, and Assistant

Secretary Bimal Patel, Department of the Treasury, to Staff, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis (July 2,

2020).

17

businesses from underserved markets, including minority and women-owned businesses, may

have been excluded from the PPP at the application stage. If PPP is extended, the

Administration should add a demographic questionnaire to the application form.

18