Automatic Enrolment

Review 2017:

Maintaining the

Momentum

Cm 9546

Automatic Enrolment

Review 2017:

Maintaining the

Momentum

Presented to Parliament

by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

by Command of Her Majesty

December 2017

Cm 9546

© Crown copyright 2017

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence

v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit

nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to

obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/automatic-enrolment-review-

2017-maintaining-the-momentum

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at

2017automatic.enrolmentreview@dwp.gsi.gov.uk

ISBN 978-1-5286-0148-1

ID CCS1217568844 12/17

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum

Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 1

Contents

Foreword by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 3

Executive summary 6

Introduction: Building on success 6

Three strategic problems for the future development of automatic enrolment 8

Statutory reviews 15

The Government’s next steps 15

Summary of proposals 17

Chapter 1: Introduction 19

Summary 19

Why review now? 23

The principles underpinning the review 25

Structure of the report 26

Chapter 2: Automatic enrolment: getting millions more saving 27

Summary 27

The impact of automatic enrolment 28

Contributions into pensions 30

The impact of automatic enrolment on under-saving 32

Chapter 3: Normalising and strengthening workplace pension saving 34

Summary 34

Age Criteria 35

Pension contributions from the first pound earned 40

Earnings trigger 46

Normalising pension saving 51

Flexibility in pension saving 52

Next steps 53

Chapter 4: Self-employment 55

Summary 55

Policy Direction 55

Overview 56

Who are the self-employed? 59

2 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Chapter 5: Better engagement to reinforce savings behaviour 73

Summary 73

Policy direction 74

Our engagement focus 74

Revisiting the behavioural evidence behind automatic enrolment 75

Simple words, simple language 77

Annual benefit statements that engage savers 81

Engagement and the role of employers 83

Single Financial Guidance Body 85

Technology and engagement 86

Communicating the benefits at national level 89

Chapter 6: Statutory Reviews 91

Summary 91

Section 1: Statutory Review of Alternative Quality Requirements for

Defined Benefit Schemes 91

Section 2: Statutory Review of Alternative Quality Requirement of

Section 28 Schemes 100

Statutory review of regulations in respect of Seafarers and Offshore workers 108

Annexes 109

Annex 1 - Technical operation of automatic enrolment 109

Annex 2 - Review of automatic enrolment – initial questions 113

Annex 3 - Review of Automatic Enrolment - Advisory Group Terms of Reference 117

Annex 4 - Automatic Enrolment Review Scope 119

Annex 5 - Annual benefit statement 121

Annex 7 - List of respondents to the call for evidence on:

‘Alternative Quality Requirements for Defined Benefit Schemes’ 124

Annex 8 - List of respondents to the call for evidence on:

Seafarers and Offshore Workers 125

Annex 9 - Post Implementation Review of Alternative Quality

Requirements for Defined Benefit schemes 126

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 3

Foreword by the Secretary of State for

Work and Pensions

We are committed to enabling more people to save while they are working, so that they can

enjoy greater security and independence when they retire.

Workplace pension saving is now becoming the norm for a new generation of workers. 9 million

individuals have now been automatically enrolled into a workplace scheme by their employer,

with nine out of every ten of them continuing to save. Many of those benefitting were once

poorly served or excluded from workplace pensions, but thanks to automatic enrolment, many

more women, low earners and younger people are now building an asset for their future. By

2019/20, it is estimated an extra £20 billion a year will be saved into workplace pensions as a

direct result of automatic enrolment.

We are rebuilding the UK’s savings culture. And as a pioneer of this shift in workplace pension

saving, other countries are seeking to learn from our experience.

Over this year, the government has carried out a review of automatic enrolment to consider how

to build on its success for the future. A key focus is for individuals to keep saving and to save

more after minimum contributions reach 8 per cent in 2019. But we recognise that contributions

of 8 per cent are unlikely to give all individuals the retirement to which they aspire. We also

know there is more to do to ensure that younger people, part-time workers and the self-

employed can achieve more security in later life. As per our manifesto commitment on the self-

employed, the government’s aim is to use the principles and learning of automatic enrolment to

improve pension participation and retirement outcomes among self-employed people.

This Review sets out proposals to maintain the momentum achieved so far and to build a

stronger, more inclusive savings culture for future generations. We stand ready to learn from the

contribution rate increases which will come in to effect in 2018 and 2019, and to carry out

further work on the adequacy of retirement incomes. We will then take this forward to look again

at the right overall level of saving and the balance between prompted and voluntary saving.

• We are setting out a comprehensive and balanced package of reforms which together would

increase median earners’ private pension provision by over 40 per cent and lower earners

by over 80 per cent.

• We are continuing to make saving the norm for young people, by lowering the age threshold

for automatic enrolment from 22 to 18, enabling more people begin to save. Confirming that

automatic enrolment will continue to be available to all eligible workers regardless of who

their employer is, or the sector in which they work;

• We are supporting those with low earnings and multiple jobs to save by removing the lower

earnings limit so that contributions are calculated from the first pound earned and everyone

has access to a workplace pension with an employer contribution;

4 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

• We will work to implement the government’s manifesto commitment to improve pension

participation and retirement outcomes among self-employed people by testing a number of

different approaches aimed at increasing the savings of self-employed people from 2018,

with a focus on those with low to moderate incomes. This recognises that there are 4.8

million self-employed people in the UK for whom a single saving initiative is unlikely to work.

We will then set out proposals to implement the most effective approaches at scale.

• We are underpinning this with a package of measures, and a call upon the pensions

industry, employers and wider government, to work together to deliver better engagement

with individuals on the benefits of workplace saving.

Automatic enrolment has worked to date because of the commitment and support of our key

delivery partners. In particular, over 900,000 employers across the UK have played a vital role

in making sure that their workers are now saving.

An independent Expert Advisory Group has supported this Review, led by Ruston Smith (Chair

of the Tesco Pension Fund and Tesco Pension Investment Ltd.), Jamie Jenkins (Head of

Pensions Strategy, Standard Life) and Chris Curry (Director, Pensions Policy Institute).

Through the Group’s work, we know that there is wide support for these proposals as well as

the principles which underpin them. I am very grateful for their work, as well as the enthusiasm,

ideas and insight we have received from many people and organisations across the employer,

consumer and financial services communities. This widespread support will remain critical to

sustain the success of automatic enrolment.

The government’s ambition is to implement these changes to the automatic enrolment

framework in the mid-2020s. Over the coming year, we will work to build a renewed consensus

to deliver the detailed design and implementation of our proposals. The government recognises

that while the changes being proposed will bring future financial benefits for individuals and the

UK’s longer term fiscal position, there are also significant cost consequences which will need to

be shared between individual savers, employers and government. All parties will need time to

plan for this, being mindful of the broader economic climate.

Our long term goal is that future generations can have confidence in saving through workplace

pensions and look forward to greater financial security and independence in retirement. We look

forward to continuing to work with a wide range of partners to achieve this through making

automatic enrolment sustainable for the long term.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 5

6 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Executive summary

Introduction: Building on success

We are committed to enabling future generations to achieve security in later life. Automatic enrolment

into workplace pensions has already succeeded in transforming pension saving for millions of today’s

workers. Since automatic enrolment started in 2012, workplace pension participation has increased

among eligible employees from a low of 55 per cent in 2012 to 78 per cent in 2016.

For the private sector this shift has been transformative; among eligible employees, participation has

risen by over 31 percentage points since 2012 to 73 per cent of eligible employees in 2016. The greatest

increases have been among those who have traditionally had least access to workplace pensions: the

lowest earners; younger people (those aged 20 – 29); and women. Workplace pension participation

among eligible men and women has been equalised. Total annual contributions into workplace pensions

are currently at a ten-year high of £87 billion in 2016.

In 2018 the roll-out of automatic enrolment to employers will be completed and it is estimated that

around 10 million people will be newly saving or saving more.

1

The existing policy framework will deliver

phased increases in the minimum contributions rates to 5 per cent in April 2018 and 8 per cent in 2019.

Automatic enrolment is a policy that is working. It has been based on widespread consensus about the

need to reinvigorate workplace pension saving, grounded in the work of the independent Pensions

Commission over a decade ago. Employers and private sector delivery partners have been central to

that success. Since the Pensions Commission reported the detailed design and implementation

approach have been developed by a broad delivery partnership encompassing government, regulators,

employers, payroll firms, intermediaries and the pensions industry.

CBI “Automatic enrolment is a successful policy built on sound principals – employer support is key to

this”.

USDAW “USDAW has given its full backing to auto enrolment. It has in our opinion been a fantastic

initiative, however, more needs to be done and we want to encourage Government and the pensions

industry to continue to build on the successes which have been achieved so far”.

Which? “…agrees that it has been successful in engaging workers to newly save, or save more, into a

workplace pension”.

TUC “Automatic enrolment has been a great policy success…..has the potential to become the bedrock

of workplace pension saving in the UK”.

Government is committed to building on the transformational progress that has already been made and

this report sets out a clear direction beyond 2019, so that employers, savers and the pensions industry

1

DWP (2016) Workplace pensions: Update of analysis on Automatic Enrolment 2016

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/560356/workplace-pensions-update-analysis-auto-enrolment-

2016.pdf

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 7

can understand how automatic enrolment will continue to develop into the mid-2020s, and how they will

be involved in that process.

Creating a fairer, more robust and sustainable system for the future

This Review has confirmed that automatic enrolment is making savings into a workplace pension the

new norm for millions of individuals in the UK and that overall the framework that has been established

remains the right one for individuals, employers and delivery partners.

In line with its published scope, the Review has examined three main areas: the existing coverage of

automatic enrolment and whether or not this remains appropriate over the longer term; the evidence

base concerning future contributions and how this can be strengthened; and how engagement can be

improved so that individuals have a stronger sense of ownership and are better enabled to maximise

pension saving.

In the process of examining these areas and assessing the success of automatic enrolment to date and

the challenges that remain, we have identified and considered three significant and complex strategic

problems:

1. Current saving levels risk a significant proportion of the working-age population not meeting their

retirement expectations. In addition the current structure of automatic enrolment means there are

gaps in coverage, in particular for those in low paid part-time jobs and younger workers. Employers

are facing competing burdens including the National Minimum Wage (NMW) and National Living

Wage (NLW) costs. In addressing these challenges there must be a realistic and fair balance

between the costs to employers, individuals, and the public finances.

2. A large proportion of the self-employed experience significant gaps in pension coverage and other

savings for retirement. However, most self-employed people cannot be covered by the current

design of automatic enrolment.

3. Individuals are beginning to save but for multiple reasons do not actively engage with their

pensions. The barriers to engagement with workplace pension saving that led to the introduction of

automatic enrolment remain and engagement alone will not address pension participation and

savings challenges. However, improving awareness and understanding by delivering the right

support in a simple way complements the role of automatic enrolment and provides a better

platform for voluntary saving and helps to build trust and confidence in the system.

This Review report provides analysis of the scale and nature of these problems, and government’s

assessment of where and how the current approach should be extended over the medium term. As part

of this assessment we recognise that we will need to continue to learn from the rollout of automatic

enrolment, including from impact of the phased contribution rate increases that are still to occur.

A changing delivery context

Our assessment recognises that the context in which automatic enrolment is being delivered has

changed in significant ways since it was first introduced, and that it continues to change. Improved health

and better living standards mean that individuals are living longer. Following a review of the State

Pension age, the government has set out its approach so that there is fairness across generations

2

. The

broader pensions and savings landscape has also evolved, for example, as a result of the introduction of

pension freedoms and the Lifetime ISA. The rapid growth in consumer credit presents altered risks. The

government’s ‘Help to Save’ scheme, which will be introduced from 2018, is designed to strengthen

financial resilience for those on low incomes. New ideas related to pension saving are also emerging in

this territory (including the NEST Insight Unit’s ‘liquidity and sidecar savings’ and Step Change’s

‘accessible pension savings’ models).

2

DWP State Pension age review (July 2017) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/state-pension-age-review-final-report

8 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

The economic outlook and labour market context has changed significantly, through the experience of

the financial crisis; high employment rates; the growth and diversity in self-employment; the rise of the

‘gig-economy’; low-wage growth; and the decision to leave the European Union in 2019. Rapid

technological innovation continues to change the way that people access and use information, including

how they set up their pensions.

In the course of this Review we have considered how automatic enrolment fits within this changed

landscape, those factors that have particular relevance and what steps can be taken to build in sufficient

flexibility for automatic enrolment to respond effectively to future changes.

To support this, the government intends to steward debate and develop consensus on the approach set

out in this Review while also closely monitoring the impact of the legislated contribution rate increases in

April 2018 and April 2019.

Principles

Our analysis, conclusions and direction have been underpinned by a set of core principles

3

, alongside

due regard to Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010

4

and the broader principles set out by the Pensions

Commission of fairness, affordability and sustainability.

Advisory group and stakeholder input

The Review has been supported by an external Advisory Group (including members that represent the

views of employers, individuals, pension providers and intermediaries), whose advice, insight and

challenge has informed our analysis of the issues and our direction.

We have also carried out extensive engagement with as many interested parties as possible to help

inform our approach. In addition to an initial review of evidence, we have had extensive meetings and

discussions with a broad range of individuals and organisations including those representing employers,

consumers, unions, pension providers and intermediaries.

Three strategic problems for the future development of

automatic enrolment

Strategic problem 1: Current saving levels present a substantial risk that the retirement

expectations for a significant proportion of the working-age population will not be supported. In

addition the current structure of automatic enrolment means there are gaps in coverage –

notably for those in low-paid multiple part-time jobs and younger workers.

Automatic enrolment has transformed participation in pension saving in the UK, particularly among those

who were traditionally less likely to have access to workplace pensions. In particular, participation among

private sector eligible employees (earning between £10,000 and £20,000) increased from 20 per cent in

2012 to 63 per cent in 2016.

The independent Pensions Commission identified that the State Pension, supplemented by automatic

enrolment contributions of 8 per cent of relevant earnings would deliver around half the level of savings

needed to deliver adequate retirement incomes for most individuals

5

. The Commission’s proposal was

that the remaining gap in savings levels would be met through additional voluntary saving on top of

savings from automatic enrolment contributions. Savings levels are projected to improve over time

through workplace pension saving. While there are no indications, so far, that voluntary saving for

3

DWP Review of automatic enrolment (February 2017):

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590220/initial-questions-automatic-enrolment-review.pdf

4

Equality Act 2010 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

5

Pensions Commission (2005, Appendix D, Figure D28)

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 9

retirement is rising in a significant way, there is also no evidence to date that individuals have offset

additional workplace pension saving with reduced liquid saving.

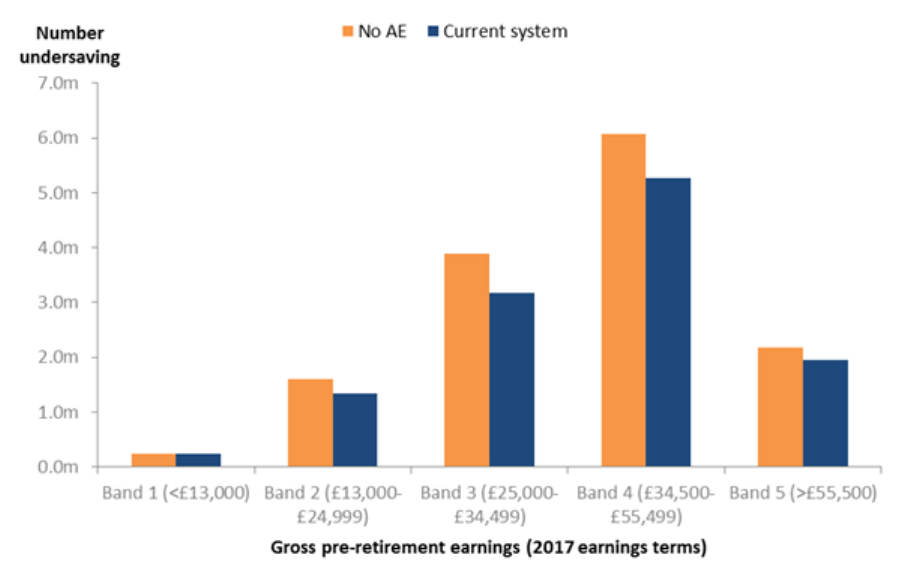

Despite the success of automatic enrolment, using the savings adequacy measure introduced by the

Pensions Commission, there are still around 12 million individuals under-saving for their retirement (i.e.

not projected to be saving enough for an adequate retirement income

6

) who make up 38 per cent of the

working age population.

Of these 12 million, taking account of the planned increases in automatic enrolment contribution rates,

some 5.7 million are ‘mild under-savers

7

’. If automatic enrolment had not been introduced, an additional

2 million individuals would now be under-saving.

Looking at under-saving by income level, the vast majority of those individuals who are under-saving -

approaching 10.4 million (87 per cent) - earn more than £25,000 a year. Around 1.6 million (13 per cent)

earn below £25,000 a year. The government intends to explore adequacy measures, but in this Review

we have focused on how best to build on statutory savings rates through automatic enrolment to

continue to address under-saving. In doing this, we recognise that it remains important to continue to

consider at what level of earnings it will ‘pay to save’ for most individuals.

Despite the gains in participation levels, some workers see more limited benefits from automatic

enrolment:

• Workers who earn more than £10,000 a year in a job are automatically enrolled, but because their

contributions are calculated from the bottom of the qualifying earnings band (£5,876) in each job,

they will miss out on a potentially significant contribution, and possibly more than once.

• Non-eligible jobholders who earn £10,000 a year or less in each of their jobs do not qualify for

automatic enrolment, even if their combined earnings exceed £10,000.

• Entitled workers who earn at or below the Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) in each of their jobs are not

necessarily entitled to an employer contribution even if they opt-in.

• Younger workers aged 18 to 21 currently miss out on automatic enrolment because the lower age

limit of 22 was based on previous National Minimum Wage (NMW) criteria which were subsequently

superseded in 2010.

6

The Pensions Commission measured adequacy using replacement rates. Replacement rate is defined as someone’s income in retirement

divided by their income in work based on average earnings for those years in work between age 50 and State Pension age. Analysis

presented classifies someone’s income is inadequate if their replacement rate does not meet a set of benchmarks used by the Pensions

Commission, the benchmarks are less than 100 per cent and different for those on different income levels.

7

Analysis presented classifies someone is a mild under-saver if they are estimated to achieve between 80 and 99 per cent of their target

replacement rate.

10 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Going forward: Review response and conclusion

• We want pension saving to be the norm when people start work, and therefore want young people

to benefit from automatic enrolment. Our proposal is to reduce the lower age limit from 22 to age

18. This change will simplify workforce assessment for employers: all eligible workers would benefit

from automatic enrolment from age 18 whoever employs them.

• We want to help lower earners build their resilience for retirement; to support individuals,

predominantly women, in multiple part-time jobs; and to further simplify automatic enrolment for

employers. We propose to change the framework for automatic enrolment so that pension

contributions would be calculated from the first pound earned, rather than from the lower earnings

limit, currently set at £5,876.

• Removing the lower earnings limit simplifies messaging: everyone earning over £10,000 and under

£45,000 a year (who meet the other eligibility rules) would be automatically enrolled by their

employer and get pension contributions on 8 per cent of all their earnings. Those earning at or

below £10,000 would not be automatically enrolled, however if they opt in they would also benefit

from pensions contributions on 8 per cent of all their earnings. The change to how contributions are

calculated would also improve the incentives for those in multiple jobs to opt-in to their workplace

pension scheme, as they would benefit from an employer contribution for every pound they earn in

every job, up to the upper earnings limit (currently set at £45,000).

• We estimate that together, these proposals would bring an extra £3.8 billion into pension saving

annually, increasing the pension pot of the lowest earners by over 80 per cent and that of the

median earner by over 40 per cent.

• Automatic enrolment is normalising saving precisely because it applies to all sectors of the labour

market. We have examined the case to exclude certain sectors from automatic enrolment but do

not propose to disturb the current arrangements which provide appropriate flexibility, for example by

allowing employers with short term workers to postpone automatic enrolment for three months.

• Alongside monitoring the impact of the phased increases in statutory minimum contributions we will

carry out further work on the adequacy of retirement income. We will use this evidence to look again

at the level of contributions into workplace pensions and the balance between statutory and

voluntary saving. In parallel we will also continue to monitor risks (including those related to growth

in consumer credit) and the evidence base concerning financial resilience to identify whether or not

interventions may be needed in future.

Consensus across stakeholders on automatic enrolment has been an important factor in its success to

date and we believe that it is important to maintain this approach when considering further developments

of the policy, such as the changes set out in this review.

Our ambition is to implement these changes to the automatic enrolment framework in the mid-2020s,

subject to discussions with stakeholders on the implementation approach during 2018/19, finding ways

to make these changes affordable, and evidence of the impact of the increases in statutory minimum

contribution rates in April 2018 and April 2019.

We recognise that employers and other delivery partners need time to plan for these changes so that

they can manage costs with certainty and will ensure that before any changes are made to automatic

enrolment, we have full discussions with stakeholders, followed by formal consultation in due course.

Our overall approach is intended to provide employers and delivery partners (including small and micro

employers, payroll practitioners and others) with the necessary stability to continue to introduce

automatic enrolment schemes for employees in the most effective way for all parties.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 11

We will also ensure that there is sufficient time between legislation and implementation to allow

employers and other delivery partners to plan for and manage change. We recognise in particular that

employers need time to adjust to other costs over coming years, before the proposals in this Review are

implemented. These include not only the phased increases in automatic enrolment contributions but

also wider changes such as the increase to the National Living Wage.

For 2018/19, the earnings trigger at which a worker is automatically enrolled will continue to be set at

£10,000. We will continue to review this threshold annually – while current evidence does not support

change now, our approach ensures that a range of factors, including affordability for employers and

whether or not it ‘pays to save’ for individuals, are kept under consideration.

This will enable employers to plan for and manage costs with more certainty. It will also ensure that for

the vast majority of individuals it will pay to save. Maintaining the trigger at £10,000 in 2018/19 will

provide employers and delivery partners (including small and micro employers, payroll practitioners and

others) with the necessary stability, recognising that they also need to adjust to other costs including the

phased increases in automatic enrolment contributions and changes such as the NLW through the

current period. Our approach will mean a gradual increase in coverage in line with increases in earnings

levels, subject to future decisions concerning the level of the earnings trigger.

Strategic problem 2: A large proportion of the self-employed population experience significant

gaps in pension coverage and/or other savings for retirement.

The self-employed are a large and highly diverse group. The UK has seen self-employment increase so

it is now around 4.8m (15 per cent of the workforce)

8

. Pension coverage among self-employed

individuals varies significantly. For some groups it is low, while others have good levels of savings and

preparation for later life. This Review has focussed on identifying the groups of self-employed people

who would most benefit from being nudged into pension saving and the potential approaches that could

achieve this.

Latest analysis suggests that there are around 2 million traditional self-employed individuals (including

contractors in the construction sector and others) who would meet automatic enrolment age and income

criteria if they were workers, but are at risk of under saving for retirement. More evidence needs to be

gathered, including on who would likely benefit from a savings intervention

9

. We will therefore develop

the evidence-base and test approaches in a number of areas to look at what works, and to improve

understanding of the practicalities of delivery.

Going forward: Review response and conclusion

We will test targeted interventions with the aim of establishing what works to increase pension saving for

the self-employed. We will use the evaluation of these to inform implementation options and will consult

on specific proposals prior to any changes to legislation.

Our work during this Review has established that there is no single or simple and straightforward

mechanism to bring self-employed people into workplace pension saving and that not all self-employed

people need help to save. We have seen a range of helpful and well considered ideas that individuals

and organisations have put forward, which we have carefully reflected on as part of the Review process.

However, we do not know from the current evidence-base, including international experience, if any of

these approaches would work in practice. Effective interventions must meet the needs of self-employed

8

ONS statistics using Labour Force Survey:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/summaryoflabourmarketstatistic

s

9

PPI (October 2017) – Policies for increasing long-term saving of the self-employed

12 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

people; they must work in practice; and they have to be affordable. These considerations are key to

ensuring changes are durable and achieve their intended aims. This is important for self-employed

people, so they can have the confidence to plan and save over the longer term.

There is no employer to automatically enrol the individual into saving so we have considered and

rejected the idea that automatic enrolment could be extended in a straightforward way to act as the

appropriate mechanism by which to bring the self-employed into pension saving. We will, however, use

the lessons from the successful principles of automatic enrolment to find an equally effective alternative

approach or approaches for self-employed people. As such we will be guided by the overarching

objective of increasing pension participation for those self-employed people for whom it would make

most economic sense to save. We will look to capitalise on touch points which provide prompts into

saving in a way that is easy to understand and as simple as possible to implement. Our aim is to

encourage pension savings at levels that are affordable to provide greater security in retirement. In the

longer term, we want to achieve a behavioural shift amongst the self-employed where regular pension

saving is seen as normal and affordable.

By robustly testing a number of approaches the government intends to identify options for self-employed

people that can work at scale. Our objective is to legislate as necessary before the end of this

Parliament, subject to learning from the tested interventions and consultation, so that these can be

deployed at the earliest possible opportunity. As with the target audience for automatic enrolment we

propose to initially try to focus on a target group of around 2 million self-employed people who broadly

mirror the automatic enrolment eligibility criteria (in terms of earnings and age criteria) and are least

likely to access saving through other routes. We recognise of course that self-employed people beyond

this target group may also benefit from saving into a workplace pension, and our objective would be to

design solutions that would be appealing and available to them as well.

The self-employed are a diverse group and their interactions with state and private sector systems differ

to the employed population. One savings intervention alone may not meet their needs.

Support with retirement saving will be most successful if it reflects the diversity of self-employed people

as well as the systems surrounding them.

We expect to test targeted, interventions from 2018, followed by consultation and any necessary

legislative changes. Following feasibility work, the trials could include:

• using the opportunity of Making Tax Digital. For example, we are exploring whether commercial

software providers could develop a routine process to facilitate pension saving for self-employed

people who need to complete a tax return;

• working with organisations that use self-employed contracted labour to understand whether or not

they can help to facilitate pension saving (for example through enhanced communications or a

prompt); and

• working with other organisations who act as touch points for the self-employed, such as banks, to

explore how technology could assist in facilitating pension saving.

A significant number of those working in atypical ways or in non-standard forms of employment already

come within the automatic enrolment framework because they are classified as workers. We will explore

whether current rules would benefit from greater clarity for them and those who engage them.

There is a group of around 1 million individuals according to some estimates – including agency workers

and those on zero hours contracts – who are working in increasingly flexible or “atypical” ways in less

standard forms of employment. In our view, a large number of these most likely come within the existing

automatic enrolment framework. We will work with the Pensions Regulator to ensure there is sufficient

clarity for them and those who engage them so that the system and its enforcement continues to operate

effectively.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 13

The government is continuing to develop its analysis in this area and has also recently announced its

intention to consult as part of the response to Matthew Taylor’s review of employment practices in the

modern economy, exploring the cases and options for longer-term reform to make the employment

status tests for both employer rights and tax clearer. If such changes are necessary we will ensure they

are also considered in relation to automatic enrolment so that there is sufficient coherence and certainty

for workers, businesses and the Pensions Regulator’s enforcement of automatic enrolment duties.

Strategic problem 3: Whilst more individuals than ever before are saving, they are not

necessarily engaged with saving nor looking to take greater personal responsibility to plan, and

save more, for their retirement.

By defaulting millions of individuals into saving and harnessing their natural inertia, automatic enrolment

is changing the way that millions of individuals behave: it has made them into pension savers and has

normalised workplace pension saving. However, many individuals are not yet engaged with their saving.

This raises the possibility that the savings habit will not be resilient, and that opportunities to encourage

individuals to save above the minimum rates could be better used.

The Review has therefore examined the role that more effective engagement can play in helping

individuals to better understand and maximise their pension savings; develop a stronger sense of long-

term personal ownership of their pension savings; and to have greater trust and confidence in the

system.

Our extensive review of the evidence-base, including international perspectives and discussions with

stakeholders, tells us that actions aimed at improving engagement will not in themselves materially

change savings behaviour.

We believe that better engagement can support the default approach underpinning automatic enrolment

by reinforcing individuals’ saving behaviour, especially where a choice exists to opt out, cease saving or

save more. Engagement can reinforce positive attitudes towards workplace pension saving and the

genuine benefits of continuing to save, and build on the development in pension saving behaviour that

automatic enrolment has delivered.

Going forward: Review response and conclusion

We want to galvanise efforts to build a sense of personal ownership of workplace pension saving

amongst individuals. Strong partnerships are a key part of that. We are setting out specific areas where

there is scope for pension providers, the advisory community and employers, working with Government

where necessary, to do more to support individuals’ engagement with their savings and to deliver better

value for their customers.

This Review has confirmed that by defaulting individuals into saving and requiring them to make a

conscious decision to opt out, automatic enrolment cuts through the barriers that prevent individuals from

saving and it harnesses inertia so that once enrolled to save they continue to do so. As a result, and in

line with theory and evidence from other countries, automatic enrolment is working: the behaviour of

millions of individuals has changed and they are now savers.

Additionally, there is also some evidence that the national automatic enrolment advertising campaign

and communication and engagement by employers, providers and the advisory community have helped

to reinforce inertia by providing the start of social norming – where people ‘like me’ were more likely to

be ‘in’ than to ‘opt out’.

As we look to evolve automatic enrolment for the future, we have the opportunity to build on the shift in

savings behaviour that has been achieved, and the positive attitudes towards workplace pension saving

that exist, through better, more effective, engagement. This will be particularly important as contribution

rates increase in the next few years.

14 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Driving up engagement is a complex challenge with a range of behaviours acting as powerful barriers

that may stop individuals engaging with pension saving. We have considered the scope for behavioural

tools, (such as ‘Save More Tomorrow’ and auto-escalation), to provide solutions. There is evidence that

these techniques can be effective where implementation has involved bespoke intensive employer

engagement and in the context of an overall employee benefits package.

However, there are significant delivery challenges associated with implementing these techniques at

scale and the current evidence-base for intervention remains limited. While we do not therefore think that

these behavioural tools are appropriate at this stage of automatic enrolment, they remain potential

options for the future and the government will continue to consider new evidence and will keep this area

under review over the longer term implementation of automatic enrolment.

It is internationally recognised that there is no single silver bullet to build better engagement. A

combination of a number of different actions and communications are needed, delivered at the right time

and in a way that meets an individual’s preferences. The Review has concluded that the key priority for

the short to medium term is to maximise opportunities to increase engagement through more effective,

consistent and personalised approaches. Our aim is to focus on building awareness, understanding and

curiosity about workplace pension saving within the context of developing social norming around

retirement saving more generally.

The consensus is that key principles should be applied to engagement. Interventions should use

positive, personal and inclusive language. They should be simple; personalised to the needs of the

individual; and timed to be relevant at ‘teachable moments’. Interventions should be framed to meet the

needs of the individual saver through understanding what those needs are.

Effective engagement will require continued collaboration and strong partnerships between government

employers, the pensions industry and advisory community, and we have identified the following areas for

work:

• Simple language is at the heart of effective engagement. Despite areas of good practice, there is a

consensus that there is still too much jargon and complicated, inconsistent, language across the

industry which is difficult for pension savers to understand and which acts as a barrier to their

interest and engagement. We welcome the work that has been done to simplify language and call

upon industry partners to collaborate to use and build upon this, and to apply it consistently across

all communication channels, both digital and traditional.

• The annual benefit statement offers an important opportunity to encourage individuals to engage but

despite the significant resources that the pension industry has invested, statements remain

complicated and overlong. They may be neglected or not understood. Individuals receiving

statements from more than one provider may find them inconsistent, adding to confusion. There is

an opportunity to provide a short, simple and consistent annual benefit statement that could be used

by all providers making it easier for individuals to understand, and we welcome work to take forward

a common approach.

• We recognise the crucial role that employers have played in the success of automatic enrolment,

and the importance of the employer/worker relationship to engagement. We welcome the

collaboration between pension scheme providers and employers that can support employers in

providing information to their workers and call upon them to continue to work closely with employers

as they develop new approaches to engagement and digital tools to support this.

• We welcome the investment made by the pensions industry in new technology and call upon it to

continue to invest in new ways. The aim should be to match other financial and retail sectors and

offer multiple ways for individuals to access their services alongside more traditional communication

channels. It is important that this reflects the needs, accessibility requirements and preferences of

all potential users so that no groups are left behind.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 15

• The government is committed to working with pension providers on pension dashboards to enable

individuals to see all their retirement income and savings information in one place in a simple and

consistent way which will provide the most effective way to use teachable moments.

• We are committed to delivering a policy and regulatory framework that supports the evolution of

automatic enrolment and recognises the needs of employers, providers and individuals, including

the need for simple, consistent language, and the creation of the Single Financial Guidance Body.

Statutory reviews

This report also outlines findings from the statutory review on the operation of the regulations on

‘alternative quality requirements for defined benefit (DB) schemes’, and specific elements of ‘alternative

quality requirements for defined contribution (DC) schemes’.

DWP carried out a call for evidence earlier in the year to obtain evidence to support the review of

alternative quality requirements for DB schemes. Responses from interested parties confirmed the

overall policy objective is being met for the vast majority of schemes to which the legislation was

targeted. Several respondents have raised areas for further simplifications; our next step will be to

consider some of those suggestions in more detail. The next statutory review will be in 2020.

The review requirements in respect of the alternative quality requirement for DC schemes requires the

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions to carry out a review at least once every three years to ensure

that, under the alternative quality requirement, contributions will not be less than the statutory minimum

for at least 90 per cent of job holders. Commitments for a periodic review were introduced as a

safeguard to minimise the risk of jobholders receiving less than the minimum level of contributions, as

provided for under relevant quality requirement. Our assessment has confirmed the ‘90 per cent test’

continues to be met. The next statutory review will be carried out in 2020.

The Government’s next steps

This Review has confirmed that automatic enrolment into workplace pensions is transforming pension

saving for millions of today’s workers. Workplace pension saving is now normal for millions of workers in

the UK and by 2018, 10 million individuals will be saving for the first time, or saving more.

The Review has also confirmed that overall, the framework that has been established for the delivery of

automatic enrolment remains the right foundation for workers, employers and delivery partners, and that

automatic enrolment duties will continue to apply to all employers, regardless of sector and size.

The package the government proposes in response to the Review findings sets a clear direction to build

a more robust and inclusive savings culture, specifically to support younger generations through the

opportunity to build up assets to allow them to have a more secure retirement.

The government is proposing a comprehensive and balanced approach to build on the success of

automatic enrolment to date and maintain momentum, whilst recognising that the costs will be shared

between individuals, families, employers and taxpayers, and that all parties will need time to plan for

change.

Our approach has a number of elements and to support this, the government intends to steward debate

and develop consensus on the detailed design and implementation approach.

Going forward:

• Our ambition is to implement these changes to the automatic enrolment framework in the mid-

2020s, subject to discussions with stakeholders on the implementation approach during 2018/19,

finding ways to make these changes affordable, and evidence of the impact of the increases in

statutory minimum contribution rates in April 2018 and April 2019. Our discussions with

stakeholders during 2018/19 will allow us to build consensus on the future direction of travel and

16 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

shape and develop more detailed plans and implementation timetable that can then form part of the

formal consultation.

• Government will monitor the impact of the increases in minimum contribution rates in 2018 and

2019 to inform discussions with stakeholders about future contribution rates and also to better

understand how costs from changes to automatic enrolment are shared between individuals,

employers and taxpayers.

• We will begin testing targeted self-employment interventions in 2018 with a view to evaluating them

in 2019 to inform implementation options and costs, and will examine whether current legislation

and/or guidance requires clarification around the eligibility of workers in atypical ways or in non-

standard forms of employment to be automatically enrolled.

• DWP will report on the feasibility study for the Pension Dashboard in spring 2018. The Single

Financial Guidance Body will be in place after autumn 2018.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 17

Summary of proposals

Government wants to continue to normalise pension saving among workers; help lower earners build

resilience for retirement; support individuals, predominantly women, in multiple part-time jobs; and

simplify automatic enrolment for employers. Therefore:

• Automatic enrolment duties will continue to apply to all employers, regardless of sector and

size.

• We want pension saving to be the norm when most individuals start work. We therefore want

young people from age 18 to benefit from automatic enrolment and our ambition is to lower

the age criteria from 22 to 18. This would bring a further 900,000 young people into automatic

enrolment. It also simplifies the workforce assessment for employers. All eligible workers will benefit

from automatic enrolment from age 18 whoever employs them.

• Our ambition is to change the framework for automatic enrolment so that pension

contributions are calculated from the first pound earned, rather than from a lower earnings

limit of £5,876 (in 2017/18). As part of the proposals in this review, we would also remove the

‘entitled workers’ category. The removal of the lower earnings limit would bring an extra £2.6

billion into pension saving, improve incentives for individuals in multiple jobs to opt-in to pension

saving because they would get an employer contribution for every pound they earn in every job. It

would also help to simplify the way many employers assess their workforce and calculate

contributions.

• As a result of these simplifications eligible workers would have access to a workplace pension with

an employer contribution – with those eligible workers aged 18 to State Pension age being

automatically enrolled.

• Recognising that these changes present significant additional costs, in particular for employers and

the Exchequer and significant changes for individuals, we will seek to better understand the full

impacts for all stakeholders as part of the consultation process and will explore cost mitigations and

funding options. We plan to do a full impact assessment of the increased costs for businesses. For

employers, we will explore cost mitigations as part of any relevant consultation.

• We have reviewed the earnings trigger for automatic enrolment, and this will remain at

£10,000 a year in 2018/19, subject to annual review. Whilst current evidence does not support

change now, our approach ensures factors, including affordability for employers and whether or not

it ‘pays to save’ for individuals, are kept under consideration.

• We will continue to monitor and evaluate the impact of increasing contributions and will

carry out further analysis to inform a longer-term debate on the right balance between

statutory contribution rates and voluntary additional retirement savings.

• A proportion of the 4.8 million self-employed people are at risk of under-saving for their retirement.

We will work to implement the Government’s manifesto commitment by testing targeted

interventions – including through the opportunity of Making Tax Digital – to identify the most

effective options to increase pension saving among self-employed people. We will provide

more information about the trial areas during 2018, following feasibility work.

• While many of those working in atypical ways or in non-standard forms of employment already

come within the automatic enrolment framework, following the Taylor Review, we will explore

whether there is a need for greater clarity to ensure that those workers who are eligible are

automatically enrolled into a workplace pension scheme.

18 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

• Automatic enrolment has worked. The savings behaviour of millions of individuals has changed so

they are now savers: workplace pension saving has become normal. Effective engagement can

reinforce individual’s saving behaviour, supporting the social normalisation, especially where a

choice exists to opt out, stop saving or save more. We want to support the ability of individuals

to engage with, and have a sense of greater personal ownership for, their workplace pension

saving so that they can plan for the future.

• This report sets out specific areas where there is scope for pension providers, the advisory

community, employers and government to build on existing and develop new initiatives that will

support individuals’ engagement with and personal ownership of their savings – while delivering

better value for customers. We are calling on partners to take forward work in these areas.

Overall, this package will build on the success of automatic enrolment and create a fairer, more robust

and sustainable system for the future which balances the needs of individuals, employers and tax-

payers.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 19

Chapter 1: Introduction

Summary

This chapter outlines how automatic enrolment is transforming retirement saving for millions of today’s

workers. It is a policy that is delivering. So far, 9 million workers on whom the policy was targeted –

including younger people (aged 22 – 29), women and lower paid workers – are now building up savings

for their future, many of them for the first time. This success has been based on widespread consensus

about the need to revive workplace pension saving. Its successful delivery and implementation is based

on a broad partnership between government, its delivery bodies and our stakeholders. Employers,

together with their payroll providers, associated experts and the pensions industry, have made

workplace pensions a reality for millions of today’s workers.

This chapter also describes key elements of the current framework of automatic enrolment and the

existing eligibility rules. This framework has evolved over the last decade, benefiting from the insight of a

broad partnership of organisations in the public and private sector and from across the delivery chain –

including the Pensions Regulator; NEST; the pensions and payroll industries; countless intermediaries

and many other experts who freely contributed their time to helping improve the delivery of automatic

enrolment. Together, we have designed and implemented a policy that works well in practice, taking

opportunities to streamline and improve the framework and the delivery approach wherever possible.

Employers have played a particularly crucial role in delivering automatic enrolment for their workers.

This chapter then outlines the background and scope of the 2017 review of the policy and operation of

automatic enrolment and how the government has carried out the review process. It sets out the

structure for this review report, focussing on the three strategic challenges (outlined in the executive

summary); the statutory review requirements; and the technical operation of automatic enrolment.

Automatic enrolment – increasing security in later life

The roll-out of automatic enrolment since 2012 has been a huge success. The previous decade long

decline in workplace pension participation has been reversed. Automatic enrolment is improving pension

participation among all age groups, particularly for younger workers (those aged 22 – 29). It is equalising

workplace pension saving among men and women. Many individuals who historically did not have

access to good quality pension provision or who had no access to a pension whatsoever are now

building an asset for their future. The headline statistics are impressive.

Since 2012 9 million individuals have been automatically enrolled, with over 900,000 employers having

met their automatic enrolment duties. By 2018, we estimate that around 10 million workers will be newly

saving or saving more as a result of automatic enrolment, of these 3.6 million are women

10

.

In 2016, the proportion of eligible

employees participating in a workplace pension increased to 78 per

cent, an increase of 23 percentage points from 2012.

11

In 2016, the total amount saved annually in workplace pensions by eligible savers was £87.1 billion:

• £26.2 billion from employee contributions,

10

6

DWP (2016) Workplace pensions: Update of analysis on Automatic Enrolment 2016

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/560356/workplace-pensions-update-analysis-auto-enrolment-

2016.pdf

11

DWP (2017) Official statistic on workplace pension participation and savings trends of eligible employees: 2006-2016:

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/workplace-pension-participation-and-saving-trends-2006-to-2016

20 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

• £52.1 billion employer contributions, and

• £8.8 billion from tax relief on individual contributions

12

.

Following implementation of the reforms, under the government’s current estimates a further £20 billion

will go into workplace pension savings every year by 2019/20.

Background – what is automatic enrolment?

Automatic enrolment into a qualifying workplace pension was one of the key recommendations of the

Pensions Commission, which reported in October 2004 and November 2005. The Pensions Commission

looked at the future of retirement saving in the context of declining workplace pension participation and

increasing longevity. The Commission identified that between 9.6 and 12 million individuals were under-

saving, and recommended the creation of a vehicle – automatic enrolment – for saving for workers who

did not have access to a workplace pension. This would be one part of an overall approach to retirement

income, with the State Pension and voluntary savings making up the rest.

The policy intent was to increase the number of workers participating in workplace pensions and to

increase the total amount saved into them. This was to be achieved by enabling individuals who did not

have access to a workplace pension to start saving, and for their contributions to be supplemented by

employer contributions, and usually tax relief.

The approach was informed by behavioural analysis which showed the beneficial effects of defaulting

individuals into pension saving and harnessing the power of inertia. In this way the barriers to pension

saving presented by individual’s behaviours, in the face of the complexities of pension saving, could be

overcome.

Automatic enrolment has been targeted at individuals on low to moderate incomes who did not have

ready access to the existing private pensions market, but it has been framed in a way that recognises

workplace pensions may not make economic sense for some low-paid workers.

The core design of automatic enrolment was established under the Pensions Act 2008. An independent

Review in 2010 – Making Automatic Enrolment Work (MAEW) - confirmed the design in a number of

important areas, and made refinements to the original policy. In particular, the reviewers recommended

that all employers should provide a pension for eligible workers and that NEST would continue to be

needed to address the provision gap in the pensions’ market; in addition they proposed the introduction

of postponement to allow employers to more effectively manage the process of enrolling new workers.

The Pensions Act 2011 and subsequent secondary legislation implemented MAEW’s recommendations.

The design of automatic enrolment is underpinned by key pieces of secondary legislation

13

. We have

revisited some of these conclusions during the course of this Review (this is set out at Chapters 2 and

3).

While designed using a default approach, which means that eligible workers are automatically enrolled,

automatic enrolment recognises the principle of personal choice and stops short of compulsion, by

enabling workers to opt-out if they consider that pension saving is not right for them.

The current automatic enrolment framework

The Pensions Act 2008 specifies that every employer in the UK must make arrangements whereby their

eligible workers become active members of a qualifying pension scheme and pay certain minimum

contributions into the scheme. This is the core automatic enrolment duty placed on employers. A

12

DWP (2017) Official statistic on workplace pension participation and savings trends of eligible employees: 2006-2016.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/workplace-pension-participation-and-saving-trends-2006-to-2016

13

The Employers’ Duties (Implementation) Regulation 2010 (S.I. 2010/4); The Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Automatic

Enrolment) Regulations 2010 (S.I. 2010/772); and The Employers’ Duties (Registration and Compliance) Regulation 2010 (S.I. 2010/5).

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 21

comprehensive explanation of the process is set out in the automatic enrolment guidance for employers

on the Pension Regulator’s website.

14

Automatic enrolment has been gradually rolled out in ‘stages’ since October 2012, starting with the

largest employers

15

. Employers’ staging dates determine when they must have enrolled their eligible

workers, and require them to submit a Declaration of Compliance, to the Pensions Regulator, to confirm

that they have met their legal duties. Employers have an ongoing duty to monitor the age and earnings

of their workers and to enrol them at the point they meet the eligibility criteria. The planned ending of the

staging profile means that, since October 2017, newly created PAYE employers have had near

instantaneous automatic enrolment duties from the point at which they take on a qualifying worker. This

was a design feature of the reforms in the expectation that understanding and complying with automatic

enrolment duties would, over time, become part of the normal process of setting up a business; in the

same way that new employers are expected to deal with tax and national insurance from the outset.

Workers meet the eligibility criteria and must be automatically enrolled by their employer if they are:

• not already an active member of a qualifying workplace pension scheme on the automatic

enrolment date;

• at least 22-years-old;

• below State Pension age;

• earning more than £10,000 (2017/18) a year (or £833 per month or £192 per week); and

• working or ordinarily working in GB (under their contract).

Workers earning £10,000 or less can choose to ‘opt-in’ to a qualifying scheme and will be entitled to an

employer contribution if they earn more than £5,876 (the LEL). Automatically enrolled workers can

choose to opt-out but employers must not seek to persuade people to do so. If workers choose to opt-out

within the first month of being enrolled, they are entitled to a refund of their contributions. Every three

years employers have to automatically re-enrol their eligible workers.

An employer can delay the date they must automatically enrol an eligible worker into a qualifying

workplace pension scheme by up to 3 months. In some cases they may have been able to delay

application of the automatic enrolment duties for longer if they have either:

• a ‘defined benefit’ pension scheme; or

• a ‘hybrid’ pension scheme (a mixed benefit scheme) that allows a worker to take a defined benefit

pension

An employer must inform workers:

• about the delay in writing; and

• that in the meantime they may by notice require the employer to enroll them in a pension scheme.

There are several categories of workers – Table 1.1 refers.

14

http://www.thepensionsregulator.gov.uk/en/employers

15

Employers had the option to opt-in to automatic enrolment duties before the start of staging.

22 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Table 1.1: Categories of worker

Age

Earnings

16-21

22-SPa

SPA-74

Lower earnings threshold

(£5,876 in 2017/18) or below

Entitled worker

More than lower earnings

threshold up to and including

the earnings trigger for

automatic enrolment

(£10,000)

Non-eligible jobholder

Over earnings trigger for

automatic enrolment

Non-eligible

jobholder

Eligible jobholder

Non-eligible

Jobholder

Contribution rates

Statutory minimum contributions for automatic enrolment are currently 1 per cent of a band of qualifying

earnings for both employees and employers (total 2 per cent). Most people will receive tax relief from

Government on their contributions. The automatic enrolment earnings band is annually reviewed – it is

currently aligned with the upper and lower limits for National Insurance contributions (which are £5,876

to £45,000 for 2017/18). From April 2018, the next significant phase of automatic enrolment commences,

with the gradual increase in statutory minimum contribution rates. The legislated changes to contribution

rates to 8 per cent in April 2019 are shown in table 1.2 below.

A key focus is retention, in terms of the continuing coverage of the policy and contribution increases, so

that individuals keep saving into their pension and save more. We will be working hard to ensure that

both employers and individuals respond positively to these steps which will complete the delivery of the

original design of automatic enrolment.

Table 1.2 Contribution rates

Phasing Period

Minimum

employer

contribution

% of

qualifying

earnings

Worker

contribution % of

qualifying

earnings

(including

employee tax

relief)

Total Contribution

% of qualifying

earnings

Oct 2012 to March 2018

1

1

2

April 2018 to March 2019

2

3

5

April 2019 onwards

3

5

8

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 23

Details of eligibility criteria and framework are provided on gov.uk

16

and full guidance is available for

employers on the Pension Regulator’s website.

17

Consensus

Automatic enrolment was developed with broad support and consensus across the political spectrum,

employers, the pension industry and trade unions amongst others. This Review, and the engagement

with stakeholders that has underpinned it, has been part of renewing the consensus going forward, in

recognition that the successful evolution of automatic enrolment requires a continued partnership

approach.

People are saving, but they are not yet saving enough to ensure that they will have the retirement they

may want. This review has focussed on how to build on the success so far, confirm the approach, and

setting out how the policy will continue to evolve over the next decade so that we can continue to enable

people to save and plan towards security in retirement.

Why review now?

The government’s objective with this Review is to set out the medium term direction for automatic

enrolment in order to build on the success of the policy into the 2020s. In doing this, we recognise the

need to provide employers and others with certainty on the intended direction so that they have sufficient

time to plan and so that there is opportunity to develop consensus on the approach and its

implementation. A common objective shared by many delivery partners is to enable individuals to save

and save more: this review provides opportunity to do that, mindful of the multiple changes in the

operating environment and the need to ensure the UK system remains affordable and resilient for the

longer term.

We have revisited the challenge of under-saving that automatic enrolment was designed to address,

reflecting on what has been achieved to date, considering whether the target population remains the

right one and looking at how to evolve automatic enrolment for the future. This is explored in chapter 2.

As noted in the Executive Summary, since 2012, there have been a variety of changes to the context in

which automatic enrolment is being rolled-out. We recognise also that automatic enrolment is still

rolling-out. The full implementation of the current framework of automatic enrolment to small and micro

employers will be completed in 2018. The scheduled phasing of increases means that minimum

contribution rates will not increase to 8 per cent until April 2019. Our approach to developing the

evidence base for future of automatic enrolment recognises that we will not have complete evidence

about the impact of the increases to 5 per cent and 8 per cent until 2019/2020.

There are statutory requirements to review at this point: the alternative quality requirements for defined

benefit schemes (section 23A of the 2008 Act), and the test in relation to alternative quality requirements

for defined contribution schemes (section 28 of the 2008 Act).

Section 74 of the 2008 Act also provides for a review of the NEST annual contribution limit and the

transfer restrictions on or after 2017. Secondary legislation passed in 2015 has effectively removed the

need for this element of the review as it substantively dealt with both matters.

16

https://www.gov.uk/workplace-pensions/joining-a-workplace-pension

17

http://www.thepensionsregulator.gov.uk/en/employers

24 Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum

Scope of the Review

This Review was announced by the then Minister for Pensions, Richard Harrington, in a written

statement to the House of Commons on 12 December 2016, see Annex 4, which confirmed the scope

and proposed automatic enrolment thresholds for the 2017/18 financial year.

The Minister announced that the main focus of the Review would be to ensure that automatic enrolment

continues to meet the needs of individual savers, looking at the existing coverage of the policy, and

considering the needs of those not currently benefiting from automatic enrolment, including the self-

employed.

The Minister also announced that the Review would be an opportunity to strengthen the evidence around

appropriate future contributions into workplace pensions, and would consider how engagement with

individuals can be improved so that savers have a stronger sense of personal ownership and are better

enabled to maximise savings.

Finally, the Statement confirmed that the Review would consider whether the technical operation of the

policy is working as intended and whether there may be any policies which disproportionately affect

different categories of employers or could be further simplified.

How the government has carried out the Review

The Review has been carried out by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), working closely with

HM Treasury, and with support from an external advisory group of experts appointed to provide advice,

insight and a challenge function.

This advisory group was asked to consider three themes:

• Strengthening the engagement of individuals with workplace pensions so that they have a stronger

sense of long-term personal ownership and are better enabled to understand and maximise

savings.

• The existing coverage of automatic enrolment and the balance between enabling as many people

as possible to save in a workplace pension whilst ensuring that it should make economic sense for

them to be included.

• Strengthening the evidence base around appropriate contributions into workplace pensions.

The group comprised three co-chairs each leading on a key theme within the review, with supporting

membership from a range of experts: Ruston Smith (Chair of the Tesco Pension Fund and Tesco

Pension Investment Ltd.) – strengthening personal engagement; Jamie Jenkins (Head of Pensions

Strategy, Standard Life) – coverage of automatic enrolment; and Chris Curry (Director, Pensions Policy

Institute) – evidence base on future contributions.

The group met 8 times between February and November 2017. In addition to meetings of the full

advisory group, the three co-chairs worked closely with the DWP team on the gathering of stakeholder

views, and to define the work programme and report conclusions.

The work of the group was put on hold during the purdah period preceding the general Election on 8

June 2017. The membership and terms of reference for the group (Annex 3) were confirmed by the new

Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion, Guy Opperman MP.

The work of the Review was informed by extensive engagement by DWP and the advisory group co-

chairs with stakeholders from interest groups including: employer representatives; consumer

representatives; pension providers; professional advisors; the Pension Regulator; other government

departments including HM Treasury, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and

the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Automatic Enrolment Review 2017: Maintaining the Momentum 25

DWP carried out the engagement work in two stages. First it published an initial set of questions on 8

February 2017, with a deadline for responses on 22 March 2017. Comments were invited and received

from a spectrum of interests including workers, employers, and employee representatives, pension

industry professionals, including occupational workplace pension scheme administrators, payroll

administrators, accountants, payroll bureaux, independent financial advisors, employee benefit

consultants, and the general public (Annex 6). Following this initial review of evidence, DWP undertook a

deeper examination of the issues raised through discussion with stakeholders between April and

November 2017.

The principles underpinning the review

Our analysis, conclusions and direction have been underpinned by a set of core principles

18

, alongside

due regard to section149 of the Equality Act (the Public Sector Equality Duty) and the broader principles

set out by the Pensions Commission of fairness, affordability and sustainability. As we develop and

consult on our proposals going forward, they will (as appropriate) be subject to more detailed equality

impact analysis, the findings of which will be published.

This report should be read in conjunction with the Automatic Enrolment 2017 Review: Analytical Report

19