Antioch University Antioch University

AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive

Antioch University Full-Text Dissertations &

Theses

Antioch University Dissertations and Theses

2023

Mind Wandering in Daily Life: A National Experience Sampling Mind Wandering in Daily Life: A National Experience Sampling

Study of Intentional and Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes Study of Intentional and Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes

Reported by Working Adults Ages 25 – 50 Reported by Working Adults Ages 25 – 50

Paula C. Lowe

Antioch University - PhD Program in Leadership and Change

Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds

Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Educational

Psychology Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Industrial and Organizational Psychology

Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, School Psychology Commons, Social Psychology Commons,

and the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Lowe, P. C. (2023). Mind Wandering in Daily Life: A National Experience Sampling Study of Intentional and

Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes Reported by Working Adults Ages 25 – 50.

https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/915

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Antioch University Dissertations and Theses at

AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Antioch University Full-Text

Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For

more information, please contact [email protected].

MIND WANDERING IN DAILY LIFE: A NATIONAL EXPERIENCE SAMPLING STUDY

OF INTENTIONAL AND UNINTENTIONAL MIND WANDERING EPISODES

REPORTED BY WORKING ADULTS AGES 25–50

A Dissertation

Presented to the Faculty of

Graduate School of Leadership and Change

Antioch University

In partial fulfillment for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

by

Paula C. Lowe

ORCID Scholar ID: 0000-0001-6888-2933

February 2023

ii

MIND WANDERING IN DAILY LIFE: A NATIONAL EXPERIENCE SAMPLING STUDY

OF INTENTIONAL AND UNINTENTIONAL MIND WANDERING EPISODES

REPORTED BY WORKING ADULTS AGES 25–50

This dissertation by Paula C. Lowe has

been approved by the committee members signed below

who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of the

Graduate School of Leadership & Change

Antioch University

in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

Dissertation Committee:

Donna Ladkin, PhD, Committee Chair

Carol Baron, PhD

Claire Zedelius, PhD

iii

Copyright © 2023 by Paula C. Lowe

All Rights Reserved

iv

Dedicated To

George A. Lowe

I intentionally mind wander creative thoughts about you in the past

while at my work doing demanding tasks and feeling great!

v

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful for the privilege to conduct this research under the supervision of a

committee of original thinker women. Thank you to my esteemed methodologist, Dr. Carol

Baron, who guided this robust study. Your curiosity and enthusiasm, your breadth of skill and

experience, your sense of humor and kindness, these helped form my sense of purpose and

contribution. I thank Dr. Claire Zedelius for mentoring my critical thinking in the field of mind

wandering research, and through your own publications, demonstrating how to transform

curiosity into inquiry. Thank you to my committee chair, Dr. Donna Ladkin, for your insistence

that my research contribute to the field of leadership and change as this study broke new ground

both in findings and methodologies.

To Richard Ferraro, my inventor expert partner. Thank you for every reason of thank

you! And for inventing GloEvo to keep me focused! To Georgia Ferraro, MBA, from sampling

to SPSS to data visualization, you have been insightful and unflappable. Thank you for your

research director expertise! To Ricco Ferraro, MSDS, I am grateful for your tutoring in

Mahalanobis distance testing and your “that’s great!” when I was giddy about findings. To Chris

Eberl, thank you for logo, ads, and bright ideas!

To Jess, thank you for always, always believing I could do this. To Henry and Sienna,

“thanks a lot for the trucks, Legos, dinosaurs, and playdough I got!” as I lived my study.

To Alyce Lowe, my scholar mom who raised a big family (me #4 out of 9) and achieved

her college degree when several of us were married. Thank you for every time you said, I know

you can do this, Paulie. To my siblings, especially BFF Sarah, for pushes and participants, and

Alex, for everything you took on because I couldn’t, and Winnie, Maria, Katie, Anna, George,

and like a sister Martha. To Laura, Maxine, Monica, Miriam, Sasha, Sue, Larissa, Phyllis, Barb,

well, just forever thank you, ladies!

vi

Oh Dissertation Study Buddies, Dr. Kelly Hart Meehan, Doctoral Candidate Nora

Malone, Dr. Sara Frost, and Dr. Rosalind Cohen, I would have been stuck in the mud without

your wisdom. Our years of Tuesday night zooms and day-to-day texts, particularly Dr. Sara

Frost’s image of the horse at the bottom of the staircase, saved me from debilitating isolation.

We have given each other the gift of listening. And colleagues in Cohort 15, thank you for

lighting the path!

Expiwell proved an outstanding experience sampling company with a terrific smartphone

app. I thank Omar Pineda, Expiwell CTO, who was truly at the ready. Once underway, my data

collection was a marathon with participants joining in and finishing along the route. Omar

assured high quality and quantity of experience sampling data.

I am grateful to the marvelous faculty at Antioch University Graduate School of

Leadership and Change. I thank Dr. Jon Wergin, my kind advisor, whose book, Deep Learning

in a Disorienting World (2020), emboldened my curiosity and disquietude; Dr. Steve Shaw, for

being a wizard of library services; and Dr. Laurien Alexandre, fearless PhDLC leader, for

leading during change.

And for courage, I thank Dr. Robert Jackler, otologist-neurotologist at Stanford

University Health Care, who has provided care for my neurofibromatosis type 2 and acoustic

neuroma. You knew what needed to be done, yet you also looked me in the eye and said, “go out

and live your life” and timed what I need so I could finish this dissertation. That you know my

brain better than I do has freed me from anxiety to conduct research about thinking in real time. I

am ready to do what needs to be done.

vii

ABSTRACT

MIND WANDERING IN DAILY LIFE: A NATIONAL EXPERIENCE SAMPLING STUDY

OF INTENTIONAL AND UNINTENTIONAL MIND WANDERING EPISODES

REPORTED BY WORKING ADULTS AGES 25–50

Paula C. Lowe

Graduate School of Leadership and Change

Yellow Springs, OH

Numerous researchers have investigated thinking that drifts away from what the individual was

doing, thinking that is known as mind wandering. Their inquiries were often conducted in

university lab settings with student participants. To learn about mind wandering in the daily life

of working adults, this experience sampling study investigated intentional and unintentional

mind wandering episodes as reported by working adults, ages 25–50, living across the United

States. In this age frame, work and family responsibilities have increased in complexity and

overlap. Using a smartphone app, participants were randomly notified to answer experience

sampling surveys six times a day for up to five days. Eight questions concerned frequency,

intentionality, and the descriptive characteristics of thought type, thought content, temporality,

context, context demand, and emotion. Based upon 7,947 notification responses and 4,294

reported mind wandering episodes, the research findings showed that mind wandering is a

common thinking experience in working adult daily life and is differentiated by intentionality,

parent status, and gender. Parents reported more frequent mind wandering and intentional mind

wandering episodes than nonparents. Episode thought type was most often indicated as practical

thought. Episodes were more often reported as having the content related to context although out

of context mind wandering episodes were also highly reported. Context demand and emotion at

the time of the notification were related to mind wandering episode frequency and were further

differentiated by intentionality, parent status, and gender. Working parents reported mind

viii

wandering episodes during higher demand, particularly male parents, than nonparents. By

generating new knowledge about the thinking life of working adults, this study’s results and

methodology contribute to the fields of leadership and change, thought research, intrapersonal

and interpersonal psychology, work and family studies, and education. Future studies focused on

underlying factors related to the mind wandering of working adults and the differences between

parent and nonparent mind wandering may inform our understanding of working adult mind

wandering. This dissertation is available in open access at AURA: Antioch University

Repository and Archive (https://aura.antioch.edu/) and OhioLINK ETD Center

(https://etd.ohiolink.edu/).

Keywords: mind wandering, off-task thinking, mind wandering intentionality, thought type,

thought content, temporality, context demand, emotion, leadership, intrapersonal psychology,

neuropsychology, productivity, boundary theory, working parent, nonparent worker, atelicity,

kin care, creative thinking, experience sampling, participant level data analysis, episode level

data analysis

ix

Table of Contents

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... xiii

List of Figures* ............................................................................................................................ xvi

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1

The Problem in Practice .................................................................................................................. 3

Mind Wandering Animates Human Experience ............................................................................. 6

Research Purpose, Questions, Significance .................................................................................... 8

Study Purpose ............................................................................................................................. 9

Overall Research Question ....................................................................................................... 10

Study Significance .................................................................................................................... 11

Significance for Leadership and Change .............................................................................. 11

Significance for the Field of Psychology .............................................................................. 14

Researcher Background and Positionality .................................................................................... 16

Study Population ........................................................................................................................... 18

Working Parents........................................................................................................................ 19

A Sample Not in a Lab.............................................................................................................. 22

Study Variables ............................................................................................................................. 23

Mind Wandering ....................................................................................................................... 23

Intentional and Unintentional Mind Wandering ....................................................................... 24

Descriptive Variables ................................................................................................................ 25

Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 26

Organization of Dissertation ......................................................................................................... 27

CHAPTER II: REVIEW OF LITERATURE ............................................................................... 28

Working Adults: Parents and Nonparents ..................................................................................... 29

Thought Leaders Who Homesteaded the Field of Mind Wandering ............................................ 34

The Quest to Define Mind Wandering .......................................................................................... 39

Task-Centric Definitions ........................................................................................................... 40

Thought Movement ................................................................................................................... 41

External and Internal Contexts.................................................................................................. 42

Discussions Underlying This Study’s Definition of Mind Wandering ......................................... 44

Intentionality ............................................................................................................................. 45

Temporality, Self-Reference, and Intentionality ...................................................................... 48

x

Intentionality Related to Creative Thinking and Problem Solving ........................................... 50

Brain-Based Research ............................................................................................................... 53

Meta-Awareness and Intentionality .......................................................................................... 55

Mind Wandering Episode Descriptive Variables ......................................................................... 57

Characterizing Variables: Thought Type, Thought Content, and Temporality ........................ 58

Contextualizing Variables: Context and Demand..................................................................... 62

Emotions and Temporality ........................................................................................................ 65

Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 70

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 73

Step 1: Establish My Researcher Position and Practice ................................................................ 75

Step 2: Set Up the Quantitative Method of Experience Sampling................................................ 77

The Experiential Sampling Method .......................................................................................... 78

The Experience Sampling App ................................................................................................. 80

Step 3: Address Issues for Effective Experience Sampling .......................................................... 83

Effects of Sampling on Participants’ Performance of Tasks .................................................... 84

Framing, Satisficing, and Socially Desirable Responding........................................................ 85

Probe-Caught Versus Self-Caught Self-Report ........................................................................ 88

Effects of Meta-Awareness ....................................................................................................... 89

Complexity of Daily Life Situations ......................................................................................... 91

Probe Rate, Response Options, and Framing............................................................................ 92

Step 4: Write Onboarding and Experience Sampling Surveys ..................................................... 94

Onboarding Questions .............................................................................................................. 94

Experience Sampling Questions ............................................................................................... 95

Q1: Mind Wandering ............................................................................................................ 97

Q2: Mind Wandering Intentionality.................................................................................... 100

Q3–Q8: Descriptive Variables ............................................................................................ 104

Step 5: Collect Experience Sampling Data ................................................................................. 105

Study Sample .......................................................................................................................... 106

Step 6: Research Data Analyses Strategies ................................................................................. 111

Step 7: Ethical Considerations and Study Design Limitations ................................................... 112

Ethical Considerations ............................................................................................................ 112

Study Design Limitations ....................................................................................................... 113

xi

CHAPTER IV: FINDINGS ........................................................................................................ 116

Data Cleaning.............................................................................................................................. 117

Episode Data Recodes, Removals, and Missing Data ............................................................ 120

The Mind Wandering Episode Stories of Working Adults .................................................... 124

Research Questions ................................................................................................................... 126

RQ1: Who Are You, Working Adults? ................................................................................ 128

RQ2: How Frequently Did Working Adults Mind Wander? ............................................. 138

Participant Level Mind Wandering Frequencies ................................................................ 139

Episode Level Mind Wandering Frequencies ..................................................................... 142

RQ3: What Characterized Working Adult Mind Wandering? ............................................... 144

Thought Type ...................................................................................................................... 145

Thought Content ................................................................................................................. 151

Temporality ......................................................................................................................... 157

Context ................................................................................................................................ 164

Context Demand ................................................................................................................. 170

Emotion ............................................................................................................................... 175

RQ4: What Can We Learn by Comparing Descriptive Characteristics? ................................ 179

Question 1: Content and Context ........................................................................................ 180

Question 2: Thought Type, Content, and Temporality ....................................................... 181

Question 3: Context Demand and Emotion for Mind Wandering and Non-Mind Wandering

............................................................................................................................................. 186

RQ5: How Did Participant Comments Inform the Mind Wandering Data? ........................... 191

Conclusions ................................................................................................................................. 197

CHAPTER V: DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. 200

Key Findings ............................................................................................................................... 201

How Did Key Findings Answer My Overall Research Question ............................................... 203

Key Methodology Findings for Leadership and Change ............................................................ 205

Key Findings Contributions to the Literature ............................................................................. 208

Limitations .................................................................................................................................. 223

Recommendations for Future Research ...................................................................................... 227

Final Mind Wandering Thoughts ................................................................................................ 230

References ................................................................................................................................... 235

APPENDIX A: EMAIL INVITATIONS STUDY FLYER (POST STUDY) ............................ 245

xii

APPENDIX B: MIND WANDERING STUDY WEBSITE HOMEPAGE ............................... 246

APPENDIX C: MIND WANDERING STUDY SOCIAL MEDIA ADS .................................. 247

APPENDIX D: MIND WANDERING STUDY LOGO ............................................................ 248

APPENDIX E: MIND WANDERING STUDY WEBSITE ...................................................... 249

APPENDIX F: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR WEBSITE-DRIVEN EXPERIENCE

SAMPLING STUDY USING A SMARTPHONE APP ............................................................ 256

APPENDIX G: MIND WANDERING STUDY CODEBOOK: ONBOARDING SURVEY ... 258

APPENDIX H: MIND WANDERING STUDY CODEBOOK: SURVEY ............................... 259

APPENDIX I: DATA RECODES, REMOVALS, AND MISSING DATA DURING

SELECTED ANALYSES ......................................................................................................... 260

APPENDIX J: MIND WANDERING STUDY WEBSITE UNIQUE VISITORS .................... 261

APPENDIX K: METHODOLOGY NOTES .............................................................................. 262

APPENDIX L: PERMISSIONS AND COPYRIGHTS ............................................................. 265

xiii

List of Tables

Table 3.1 Study Questions Operationalized Into Research Questions...................................74

Table 3.2 Mind Wandering Study Onboarding Survey .........................................................95

Table 3.3 Mind Wandering Experience Sampling Survey Questions ...................................96

Table 4.1 Data Cleaning Exclusion Categories ...................................................................119

Table 4.2 Data Recodes, Removals, and Missing Data During Certain Analyses .............123

Table 4.3 Mind Wandering Experience Sampling Survey Questions .................................125

Table 4.4 Frequency and Percentage Distributions for Study Participant Demographic

Characteristics (n = 427) ......................................................................................130

Table 4.5 Frequency and Percentage Distributions for Demographics by Parent Status

(N = 427) ..............................................................................................................132

Table 4.6 Frequency and Percentage Distributions for Demographics by Gender

(N = 424) ..............................................................................................................134

Table 4.7 Frequency and Percentage Distributions for Demographics by Parent Status

and Gender (N = 424) ..........................................................................................137

Table 4.8 Participant Level Average Percentage of Notifications With All, Intentional,

and Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes by Parent Status and Gender ......140

Table 4.9 Participant Level Percentage of Notifications With All, Intentional, and

Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes by Parent Status and Gender .............142

Table 4.10 Episode Level Average Percentage of Notifications With All, Intentional, and

Unintentional Mind Wandering Episodes by Parent Status and Gender (N =

7,947) ...................................................................................................................143

Table 4.11 Thought Type for All Participants and All Mind Wandering Episodes

(N = 4,294) ...........................................................................................................145

Table 4.12 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Recoded

Thought Type for All, Parents, and Nonparents (N = 4,086) ..............................147

Table 4.13 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Recoded

Thought Type by Gender (N = 4,058) .................................................................148

Table 4.14 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Recoded

Thought Type by Intentionality (N = 4,086) .......................................................149

xiv

Table 4.15 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Recoded

Thought Type by Intentionality, Parent Status, and Gender (N = 4,086) ............150

Table 4.16 Thought Content for All Participants and All Mind Wandering Episodes

(N = 4,294) ...........................................................................................................152

Table 4.17 Mind Wandering Episode Thought Content for All, Parents, and Nonparents

(N = 3,844) ...........................................................................................................153

Table 4.18 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Thought

Content by Gender (N = 3,819) ...........................................................................153

Table 4.19 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Thought

Content by Intentionality (N = 3,844) .................................................................154

Table 4.20 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Thought Content

by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality (N = 3,844) ...................................156

Table 4.21 Temporality for All Participants and All Mind Wandering Episodes

(N = 4,294) ..........................................................................................................158

Table 4.22 Mind Wandering Episode Temporality for All, Parents, and Nonparents

(N = 4,142) ...........................................................................................................159

Table 4.23 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Temporality by

Gender (N = 4,117) .............................................................................................160

Table 4.24 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Temporality by

Intentionality (N = 4,142) ...................................................................................161

Table 4.25 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Temporality by

Parents Status, Gender, and Intentionality (N = 4,142) .......................................162

Table 4.26 Context for All Participants and All Mind Wandering Episodes (N = 4,294) ....165

Table 4.27 Mind Wandering Episode Context for All, Parents, and Nonparents

(N = 3,997) ..........................................................................................................166

Table 4.28 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Context by Gender

(N = 3,972) ...........................................................................................................167

Table 4.29 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Context

by Intentionality (N = 3,997) ..............................................................................168

xv

Table 4.30 Frequency and Percentage Distribution for Mind Wandering Episode Context

by Parent Status, Intentionality, and Gender (N = 3,997) ...................................169

Table 4.31 Mean Scores for Context Demand for All, Parent Status, Gender, and

Intentionality for Mind Wandering Episodes (N = 4,294) ..................................172

Table 4.32 Mean Scores for Context Demand for Parent + Gender and Parent +

Intentionality for Mind Wandering Episodes (N = 3,114) ...................................173

Table 4.33 Context Demand for Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality for Mind

Wandering Episodes (N = 3,114) .......................................................................174

Table 4.34 Mean Scores for Emotion for All, Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality for

Mind Wandering Episodes (N = 4,294) ..............................................................177

Table 4.35 Mean Scores for Mind Wandering Episode Emotion for Parent + Gender and

Parent + Intentionality (N = 4,294) ......................................................................178

Table 4.36 Participant Episode Reports of Mind Wandering Content and Context Within

Episode (N = 3,774) ............................................................................................180

Table 4.37 Frequency of Combinations of Mind Wandering Episodes With Certain

Thought Type, Content, and Temporality (N = 3,657) ......................................184

Table 4.38 Episode Level Analyses Means for Context Demand and Emotion Reported

When Mind Wandering and Non-Mind Wandering at the Time of the

Notification (N = 3,657) .....................................................................................188

Table 4.39 Context Demand Means for Parent Status, Gender, and Parent + Gender

Reported When Mind Wandering and Not Mind Wandering at the Time of the

Notification (N = 7,947) .....................................................................................189

Table 4.40 Emotion Means for Parent Status, Gender, and Parent + Gender Reported

When Mind Wandering and Not Mind Wandering at the Time of the

Notification (N = 7,947) ......................................................................................190

Table 4.41 Intentional Mind Wandering Episode Selected Participant Comments

(N = 352) .............................................................................................................193

Table 4.42 Unintentional Mind Wandering Episode Selected Participant Comments

(N = 262) .............................................................................................................195

Table 4.43 Sample of Participant Comments Submitted at the End of Non-Mind

Wandering Episodes (N = 303) ..........................................................................196

xvi

List of Figures*

Figure 1.1 What I Think About .................................................................................................1

Figure 1.2 Boundary-Based Human Experience Model ...........................................................7

Figure 1.3 Continuous Human Experience Model ....................................................................8

Figure 1.4 While I Work I Also Mind Wander .......................................................................10

Figure 1.5 Leader Speaks. Individuals Listen and Mind Wander ...........................................13

Figure 1.6 Madame Moitessier Seated. Madame Moitessier Mind Wandering .....................17

Figure 1.7 Working Dad You See. Working Dad Mind Wandering .......................................22

Figure 2.1 On the Job at a Warehouse … Mind wandering ....................................................30

Figure 2.2 Visions of Work Danced in Her Head ...................................................................31

Figure 2.3 Work + Parent (Featuring Denise, Brandon, Cherie, and Hank the Bunny) .........33

Figure 2.4 Mind Wandered Mother and Child ........................................................................52

Figure 2.5 Sadness Prior to Mind Wandering .........................................................................68

Figure 3.1 In the Present Betwixt Past and Future ..................................................................78

Figure 3.2 Smartphone Settings for App Notifications ...........................................................82

Figure 3.3 App Experience Sampling Calendar With Notification Timeframes ....................83

Figure 3.4 The Gaze, Chin, Hair That Mislead .......................................................................91

Figure 3.5 Intentional Mind Wandering: Open to Thoughts About Other Things ................102

Figure 3.6 Unintentional Mind Wandering: Thoughts About Other Things Popped Up ......103

Figure 3.7 Mind Wandering in Daily Life Study Website Homepage ..................................108

Figure 3.8 Social Media Ad for Mind Wandering in Daily Life Study ................................109

Figure 3.9 Mind Wandering in Daily Life Study Logo .........................................................110

Figure 4.1 Two Frequencies + Six Characteristics = Mind Wandering Episode ..................124

Figure 4.2 Working Adult Sample at a Glance .....................................................................138

xvii

Figure 4.3 Mind Wandering Frequency Participant Level ....................................................141

Figure 4.4 Mind Wandering Frequency Episode Level ........................................................144

Figure 4.5 Thought Type by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality ................................151

Figure 4.6 Content by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality ..........................................157

Figure 4.7 Temporality by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality ...................................164

Figure 4.8 Context by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality ..........................................170

Figure 4.9 Context Demand by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality ...........................175

Figure 4.10 Emotion by Parent Status, Gender, and Intentionality .........................................179

Figure 4.11 Within Episode Content + Context ......................................................................181

Figure 4.12 Mind Wandering Episode as Self-Talk ................................................................185

Figure 4.13 Within Episode: Thought Type + Content + Temporality ...................................186

Figure 5.1 Recommendations for Further Research ..............................................................228

Figure 5.2 Mind Wandering About My Unmasked Self .......................................................231

Figure 5.3 blue bird by Paula C. Lowe, 2022........................................................................234

*All drawings and poems in this dissertation are copyright protected original art and

intellectual property of Paula C. Lowe. No portion may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, including electronic storage, retrieval systems, or social

media, without the written permission of this dissertation’s author and artist Paula C.

Lowe. No snipping and/or pasting is permitted.

Artist’s note: If the drawings appear a bit rough, it was because drawing with my right

ring finger on my iPhone screen was a bit imprecise. These drawings were literally head

to hand. I hope they have added a bit of humor and insight to this dissertation.

1

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

In general, we are least aware of what our minds do best (Minsky, 1986/2014).

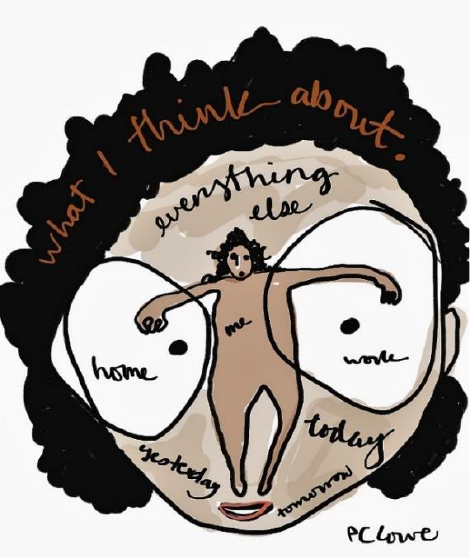

Each day billions of us go about our family, work, and community lives juggling

thoughts about home, work, self, and everything else, as shown in Figure 1.1. We are often doing

one thing while thinking about something else. The term for this is “mind wandering.”

Figure 1.1

What I Think About

Note: What I Think About. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

Mind wandering has been defined as when an individual’s conscious experience is not

tied to the events or tasks one is performing (Seli et al., 2018b). It has been described as shifts in

attention away from a primary task toward the individual’s internal information (Vannucci et al.,

2017, p. 61). Mind wandering has been established as a common brain activity that involves

thinking about things, people, and experiences that are not present in time or place. Researchers

2

have reported finding this task-unrelated thinking to occur during 30%–50% of adult waking

time (Franklin et al., 2013; Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010). Certain studies found intentional

mind wandering, reported as when an individual responded as open to mind wander, and

unintentional mind wandering that “just happened or popped up” were linked to different

contextual factors, i.e., intentional mind wandering to low task demand and repetitive task

performance, and unintentional mind wandering to high sustained and monotonous task demand

wandering (Christoff et al., 2016; Golchert et al., 2017; Seli et al., 2017b, 2018b).

What drew me to create my own study about mind wandering was that eye-popping

30%–50% of adult waking time. What do we know about this frequency of thinking in working

adult daily life? Is this a frequency dependent on lab conditions or is it all of us, every day,

everywhere, thinking about things that are not about what we are doing?

I asked these questions as a doctoral candidate in leadership and change. My rationale

was this. To lead people requires us to appreciate people as individuals. To appreciate people as

individuals means to recognize them as thinkers. Mind wandering is invisible thinking, personal

thinking, not-about-task thinking. Research has distinguished two types of mind wandering,

intentional and unintentional. By conducting this exploratory study, I wanted to expand our

understanding, where we live, work, and learn, about being a “thinker.” For as Dr. Claire

Zedelius said to me some time ago, “minds don’t think, we think.”

In this dissertation, I utilized experience sampling and quantitative analyses to examine

mind wandering in working adult daily life. I investigated mind wandering types, intentional and

unintentional mind wandering, and six descriptive variables about mind wandering episodes that

were reported by adults ages 25–50 living and working in the United States. As with mind

wandering having two manifestation, I recognized adult life as having two conditions related to

3

parenting status. Working parents had overlapping work and parenting relational responsibilities

that were constant, often overwhelming, and unending; nonparents did not have the dual

demands of working and parenting. Further, I sought to understand the relationship between

mind wandering and gender, and as this modified parent status. The dependent variable was

mind wandering, further defined as intentional and unintentional mind wandering.

In this chapter, I provide the roots of the problem in practice, mind wandering in human

experience, study purpose, and the significance of this study in the fields of leadership and

change and psychology. I then offer my researcher background and positionality, before

describing the study sample, study variables, methodology, and organization of the dissertation. I

share considerations that informed me as I designed this inquiry, moving back and forth between

selected studies and my inquiry to translate the knowledge of the field into the research I

conducted. Along the way, I offer my drawings to punctuate and illustrate my points and

reasoning with the goal of making this dissertation more accessible to you, my reader.

The Problem in Practice

Mind wandering, doing one thing while thinking about something else, has been

described as common and frequent thinking (Franklin et al., 2013; Killingsworth & Gilbert,

2010). Yet mind wandering as a thinking mode has a history of being viewed as

counterproductive. That is, our American culture hardened around being on-task (Price, 2017),

seeing mind wandering as inferring with getting things done. Because the discipline of leadership

and change is about leading people somewhere to do something, and mind wandering has been

established in research as common and frequent, and our American culture tells us to not do the

off-task thing, then, take a breath, how do we reconcile the problem in practice? That is, working

adults are supposed to be on task, thinking about task, doing task, but they are not, not always.

4

The problem in practice is that those of us in leadership and change do not know much

about a type of thinking that working adults do all day every day. Without knowledge about

frequency and descriptive aspects of mind wandering in populations we lead, we may ignore the

relevance of incorporating mind wandering in our philosophies and practices of leadership and

change. We may presume the attention and engagement of those who listen to and work with us,

even ourselves. As well, given our history of wanting more, more, more success as we work

together with others, we may inadvertently disrespect the “whole persons” with whom we work.

Just two pages ago you read that studies say mind wandering is taking up about 30%–50% of

daily life awake time. This is a stunning amount of waking time and thought in each day! This

study found these rates to be even higher for working adults in daily life.

The societal narrative about being incessantly useful long characterized off-task thinking

in trivializing ways, embedding attitudes that we were either “doing something” or wasting time.

Even the term “mind wandering” inferred not paying attention, not being where we were

supposed to be. However, Dane (2018) pointed out several benefits of mind wandering:

emerging lines of research suggest that in some respects mind wandering can be

beneficial (Mason & Reinholtz, 2015; Smallwood & Schooler, 2015). While

acknowledging that mind wandering can compromise how effectively people engage with

an assigned task, such research maintains that mind wandering can attune people to their

goals (Klinger, 2008), lead them to anticipate and plan for the future (Mason et al., 2009),

and help them generate creative solutions to challenging problems (Baird et al., 2012).

These lines of research suggest that mind wandering is not only a basic tendency of the

human mind but also an adaptive one (Baars, 2010; McMillan, Kaufan & Singer, 2013).

(Dane, 2018, p. 179)

Over the past 25 years, psychologists investigating the mind of the person and not the

agenda of productivity have produced considerable research, a selection of which is presented in

Chapter II, to challenge reductive positions on mind wandering. Psychologists asserted that mind

wandering was not a “thing” with a simple definition. For example, Damasio wrote that,

5

“Consciousness fluctuates with the situation” (2010, p. 178) and suggested that mind wandering

might be better called “self-wandering” because “daydreaming requires not merely a lateral

wandering away from the contents of the activity but a downshift to the core self. Consciousness

downshifted to core self and distracted from another topic is still normal consciousness” (p. 180).

While researchers ascertained that mind wandering was a form of thinking that was

valuable for its variegated uses and companioning consciousness, people in general may

continue to hold embedded negative views of mind wandering as wasteful or may be unaware

that mind wandering is even a state of mind. Zedelius and Schooler (2017) cautioned researchers

in the field of mind wandering to pay attention to the lay theories or mindsets that people use to

see and understand their behavior. These mindsets may not be observable, but they can be active

in individuals’ sense of what behavior is okay and what can be expected from other people.

My study participants may not have known much about mind wandering prior to being in

this study. They may even have held some “not such a good thing” mindsets. They may not have

heard that there was or is a problem in practice about lack of knowledge or consideration for

mind wandering in daily life. But they were generous and curious. They showed up. They put a

strange new app on their smartphones and allowed themselves to be notified at six random times

a day for up to five days. Working adults from all over the United States brought goodwill to my

research. I was open to be surprised, and I was surprised. I ask you, my reader, to join me in

appreciating the hundreds of people who contributed thousands of mind wandering episodes to

form the data analyzed in this study. As makers and takers, this study offers “lived knowledge”

about working adult mind wandering.

6

Mind Wandering Animates Human Experience

Before I began researching the common everyday thinking called mind wandering, I was

curious about how we can have multiple “presence of mind.” That is, we can be doing one thing

while thinking about another, mentally moving between the domains of personal/family life,

work life, and community life. We can be in a kitchen and think of work. We can be at work and

suddenly thinking about painting that kitchen. How is this possible?

I began researching mind wandering to understand how thinking animates human

experience because other theories about thinking missed this fluidity. Boundary theorists said

that individuals vary in the roles they enact, people use segmentation and integration, and

generally, people try to minimize the difficulty and frequency of role transitions and

interruptions (Ashforth et al., 2000; Ashforth et al., 2008). Researchers proposed that “working

adults develop boundaries around work and personal life domains that vary in strength” (Bulger

et al., 2007) and this would make sense with the role theory proposed in the mid-20th century

(Allen et al., 2014). However, a rigid boundary theory does not fit daily life. As an illustration,

Figure 1.2 shows Jose who appeared to have his mind on coding while he was every so often

mind wandering about his wife who was home with their newborn son. A boundary-based

experience model was not constructed for escape artist thinking. Jose was at work, but he was

thinking about Maria, was she okay?

7

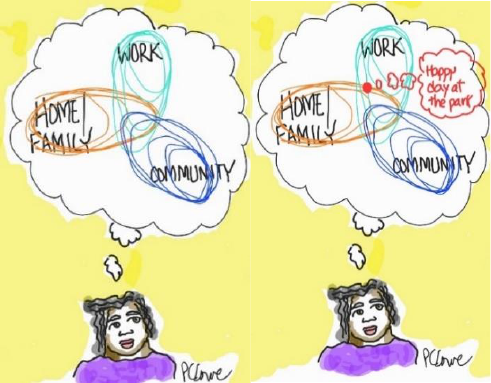

Figure 1.2

Boundary-Based Human Experience Model

Note: Boundary-Based Human Experience Model. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

A boundary-based human experience model provided a snapshot of multi-domain

thinking. However, human experience thinking seems more like a mother cat who both hunts and

runs back to check her kittens. Minsky (1986/2014) said, “you don’t understand anything until

you learn it more than one way” (p. 29). In Figure 1.3, I drew Gizelle as she worked to meet a

deadline and mind wandered about a recent day at the park when her kids. Her thinking was not

angular or static. Of the types of conscious thinking, mind wandering, the kind we do that is not

about what we are doing, could be a means for how we unify, visit, and process our human

experiences both within and beyond domains.

8

Figure 1.3

Continuous Human Experience Model

Note: Continuous Human Experience Model. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

“We’re more aware of simple processes that don’t work well than of complex ones that

work flawlessly” (Minsky, 1986/2014, p. 29). The term mind wandering has labelled the

important mental process of task-decoupled thinking. How incredible is this? Well, imagine a

day bereft of off-task thoughts—no flash to the party on Saturday, no image of fall leaves from

years gone by, no giggling anticipation about finger painting with a child. Full on-task thinking

lacks the capacity to shift our thoughts back and forth between time, people, places, needs, and

wants, and this capacity is how we imagine and remember, key parts of the formation of culture

and family life.

Research Purpose, Questions, Significance

This section speaks to this study’s purpose, research question, and significance for

leadership and change. It begins by framing mind wandering as to kin care, atelicity, and human

experience.

9

Study Purpose

The purpose of this exploratory study was to generate new knowledge about working

adult thinking known as mind wandering to expand our understanding of this type of personal

thinking in daily life. My further purpose was to see if intentional and unintentional mind

wandering frequencies and episode characteristics were different by parent status and gender for

working adults. I explored both types of mind wandering, intentional and unintentional, and both

conditions for working adults, parents and nonparents, and gender, male and female.

My intention has been to contribute this knowledge to the field of leadership and change

to enhance a new and broader appreciation of thinking processes for both leaders and those they

lead. We cannot know thoughts by looking at people. In Figure 1.4, we see Anita at her work and

imagine that her opened laptop with her eyes aimed its screen tell us how she was thinking.

However, in fact, she was visibly working and invisibly mind wandering.

As well, I wanted to contribute to the field of thought process research as the intentional

and unintentional mind wandering of working adults, and more specifically, parents and

nonparents, and by gender, ages 25–50 had not been studied. This population presented with

daily demands, responsibilities, and expectations for productivity that exceeded those of younger

adults who have often been the participants in lab-based studies.

10

Figure 1.4

While I Work I Also Mind Wander

Note: While I Work I Also Mind Wander. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

A circumstantial extra part of my purpose was to contribute knowledge about the daily

life mind wandering episodes reported by working adults at the end of the second year of the

Covid 19 pandemic. These data inform our understanding as to the ways in which working

adults, particularly parents, were mind wandering during this multi-phased pandemic.

Overall Research Question

My overall research question for this exploratory study was to investigate frequencies and

attributes of working adult mind wandering. This question was then operationalized in five

research questions presented in Chapter III and implemented in Chapter IV.

Overall Research Question: What can we learn about working adult mind wandering by

investigating the rates and characteristics of overall, intentional, and unintentional daily life mind

wandering episodes for working adults, by parent status, and gender?

11

Study Significance

This study generated data we did not have about the ways in which working adults think

in daily life. This research had not been conducted for this population, and the results of this

study have significance for both professional and lay communities.

Significance for Leadership and Change

Understanding mind wandering, thinking that is not about what an individual is doing, is

essential in a leadership doctoral program concerning leadership philosophies and practices.

Understanding the ways in which people process information is elemental for leaders to

appreciate the individuals they seek to lead. We may expect that people who gather for a work

purpose in a workspace always think about work. In this study, I informed those expectations to

consider a more realistic view of daily thinking that is quite often not about what one is doing.

The intent of this research was not to fix the ways in which we naturally think, but to reveal these

ways so we can lead “whole people” more compassionately, realistically, and effectively.

To practice ethical respect for each other in the work we do together, we can learn to

better appreciate the unseen aspects of our personhood, that even in the presence of each other,

we have thoughts of our own that are not about the public task in which we appear to be

engaged. These thoughts, perhaps especially thoughts that come and go as in mind wandering

thoughts, inform and are informed by what matters to us in our daily lives. The ethical

significance of this study lies in learning about mind wandering so we can better respect each

other's privacy of thinking as valuable, not only when that thinking is joined in common task, but

also when that thinking is personal and invisible.

The Pulse of American Worker Survey (Prudential Newsroom, 2021) concluded the

boundaries between work and life have increasingly blurred. One in three working adults ages

12

25–42 reported they planned to look for a new job after the Covid pandemic, citing how leaders

and businesses treated them during a difficult time. It is the last statement in this brief overview

that circles back to this study, “leaders need to understand what their people are thinking.” I

would adjust that to say that leaders need to understand “the ways” in which people are thinking.

As introduced at the beginning of this chapter, researchers have asserted that thirty to fifty

percent of adult mind activity during waking time is devoted to mind wandering (Franklin et al.,

2013; Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010). When leaders want to understand what employees are

thinking, mind wandering is a key thought process in which context and content, the “what

people are thinking,” can be found. The reason for understanding this thinking is not to invade

the privacy of personal thought. Instead, it is to respect that personal thought and task-based

thought are

co-existent.

Just about everything leaders assume about people as they plan to help them do this or

that depends upon how those people mentally process and internalize the information and

directions a leader sends out. As leaders conduct a meeting or speak to small groups, interact

with their staff members, or video conference with individuals, those leaders may suppose that

people think in ways that fit their messages. Yet, quite often, people do not think in those fitting

ways. People think their own thoughts about who knows what. Even leaders in the midst of

leading may think other thoughts. This difference between leader expectations and human mind

reality creates problems in practice for leaders who may just try harder, make more flow charts,

schedule more meetings, and label mind wandering as “costing us.” Figure 1.5 illustrates the

problem in practice when a leader forges on and on without recognizing individuals’ normal

consciousness.

13

Leaders may miss a simple truth: a mind is a busy machine. It is not full steam or no

steam. As this study has learned, quite often we are checking in with other content. Knowing

how frequent off-task thought, sometimes unintentional and sometimes intentional, occurs in

daily life is elemental for leaders to appreciate and work with people as they are, including

ourselves since we each mind wander and have been doing so several times while reading this

chapter. Yes, leaders are to be good listeners, but not all listening is to hear what is audible.

Figure 1.5

Leader Speaks. Individuals Listen and Mind Wander.

Note: Leader Speaks. Individuals Listen and Mind Wander. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

Perhaps the term researchers settled on, “mind wandering,” conjures an image of being

lost in a Wal Mart. Mind wandering is its own consciousness occurring in bits of time day in and

day out. With this dissertation, lodged not inside a cognitive psychology program at a university

full of human behavior research but within a leadership doctoral program, I chose to inform

leadership pedagogy that may not have considered mind wandering as a major element of

14

thinking life. I took mind wandering out of the obstacle column and into the “so if this is

happening, how do we work with it?”

This research was conducted for leaders and the people they strive to lead—people

flipping burgers, teaching children, driving front end loaders (yes, Henry, I said it) or UPS

trucks, sitting at desks or kitchen tables, picking vegetables in fields, or caring for patients. A

by-product of this dissertation may be to increase empathy for one another, letting us imagine

being in the shoes of others to find out that we too are invisibly thinking. A methodology by-

product may be to show that experience sampling within leadership and change research gathers

participant information in real time.

Significance for the Field of Psychology

This study was significant in the field of psychological research using experience

sampling as it “broke new ground” in the exploration of the mind wandering episodes of working

adults in daily life across the United States. The study was simply designed but cast a wide net to

include a large, diverse sample. This design was befitting an exploratory study as I endeavored to

determine frequencies and descriptive variables for working adult mind wandering episodes.

This research brought new knowledge to the field of psychology and opened new questions for

human behavior and neuropsychology research as articulated in Chapter V.

My inquiry was also significant as I was attentive to three topics in psychology. These

concerned familial bonds, also known as kin care. The second was about atelicity, the ongoing

nature of parenting activities. Third, the study informed human experience psychology more

broadly as data was collected in the context of the Covid Pandemic. Bringing fresh questions into

the field of mind wandering research and cross-pollinating the purposes of inquiry encouraged

looking at this phenomena by juggling our eyes.

15

I endeavored to fill a gap in the scholarly research about working adults’ daily life mind

wandering comparing the experiences of parents and nonparents. As studies on human social

motivation have rated long-term familial bonds as of primary importance to individuals across

cultures (Ko et al., 2020), I generated knowledge about the frequency and relationship of this

motivation in intentional and unintentional mind wandering and descriptive variables in mind

wandering experiences. I asked about mind wandering episode content related to children and

other family members and friends.

Secondly, I added knowledge that informs our understanding as to how parent “thinking”

about family is, by its life long and daily nature, atelic. Atelic means that a role is incomplete

because tasks are continuous and unending (Irving, 2016). While it is true that life itself could be

described as atelic, parenting is not merely, “I have to feed kids again today.” Being a parent of a

child or children is a role relationship that presents with endless responsibilities. This study did

not “prove” that parenting is atelic, but rather, this study informed our understanding of this

atelicity by exploring the thought type, content, and other descriptive variables of mind

wandering episodes.

I expanded on the lab-based research finding that mind wandering was frequently

experienced as I studied this thinking in the daily life of working people. Sharing this knowledge

with all of us, beyond academic communities, matters because, “When your experience is limited

to your home, or your workplace, or your own personal habits, you don’t have a benchmark to

see if what you are doing is common” (Des Georges, 2019, p. 1). Much of the research about

working adults experience during the 2020–2022 Covid span was statistical, i.e., census data, job

loss data, school debt data. This study generated “thinking data” of mind wandering episodes for

working adults.

16

Researcher Background and Positionality

Being a contributor to the collective good has been a central part of my work in

educational psychology, particularly on behalf of working families while I too have been a

working parent and grandparent. I have consulted for various constituencies, i.e., Head Start,

military, at-risk, working families, urban and rural schools, corporations, universities, and more.

I served as a family therapist working with individuals, trained thousands of people in multi-day

settings, taught every age, always with a passion for helping individuals appreciate themselves

and work together with others. As well, I share lived stories through poems published in

numerous journals, anthologies, and books. I am a small press publisher. As this dissertation

bears my mark, I am a line artist.

Across my work, intentional mind wandering has enabled me to “let a fly in” particularly

when pulling together a conceptual basis for a problem I wanted to explore and reveal.

Schwartz-Shea and Yanow (2012) described me as one of those who “believes that the first step

in a research design has to be the identification and definition of concepts” (p. 45) that are

informed by “what if” thinking. I also appreciate the gold to be found in “pop up” unintentional

mind wandering. Very often such thinking appears in a drawing. Figure 1.6 is a photograph I

took at the National Gallery London of a Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Perhaps Madame

Moitessier was mind wandering in that prolonged uncomfortable pose, her hand likely falling

asleep. I mind wandered her image into my art, rendered pieces of thought (see Appendix L:

Permissions and Copyrights).

17

Figure 1.6

Madame Moitessier Seated. Madame Moitessier Mind Wandering.

Note: Madame Moitsessier Seated, artist, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1856, photograph. Copyright 2022 by

Paula C. Lowe. Madame Moitessier Mind Wandering, artist, Paula C. Lowe. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

My positionality as I conducted this study has been that mind wandering is valuable, a

kind of companion type of frequent thought, a bit of conversation with self, both pop-up

unintentional and open-to intentional types. While I have unintentional mind wandering thoughts

about the sale on pillows at Wayfair, intentional mind wandering has been a resource for my

creativity, particularly inspiring me to pursue this dissertation.

My positionality for this study was not limited to my attitudes about mind wandering. It

was informed by my gratitude to the hundreds of participants in this study. As a researcher, I

recognized that each respondent episode was submitted by a mom or dad, a sister or a friend. I

respected that I was discovering the episode stories of working people, real here and now people,

not just entering data into SPSS. Because of this attitude, on days of discovery, I could be heard

hollering WOW! I was perpetually excited to tell anyone, sometimes just the coyote pup in the

bushes beyond my rural office, about my findings. It has been my privilege to spend this very

long time within this inquiry.

18

Study Population

The population for this dissertation was adults ages 25–50 living and working in the

United States. My focus concerned two conditions determined by parent status and by gender.

Adults ages 25–50 constitute millions of American workers (Fry, 2018, p. 1). I chose this age

frame for a central reason. During this span of 25 years, working adults build upon college and

job training and are in phases of early to mid-adult life. Because this study found parent status to

be a big descriptor of working adult life, this frame recognized that it takes eighteen years to

raise a child in the home, and many families have two or more children. Therefore, 25 years was

an inclusive frame within which I also looked at gender.

Working adults in this large time frame have big picture experience. Across the United

States, they have gone through major recessions, changes in the work world that reduced and

reconfigured jobs for some at critical employment stages, high costs of living, student loan debt,

social justice struggles, climate change impacts, Covid 19 pandemic, inflation, the invasion of

Ukraine, and more. Fewer and less permanent job opportunities had some moving back in with

family or friends. In the spring of 2020, only three in ten adults aged 25–40 lived with a spouse

and child, far fewer than in previous generations at this life stage (Barroso et al., 2020, p. 2).

While job opportunities and wages improved in 2021, inflation and economic uncertainties ate

away at those improvements in 2022.

Many in this study were in the generation of Millennials, ages 25–42. Reporting in

Gallup Workplace, Adkins (2021) wrote that Millennials holding jobs have been estimated at 56

million, representing 35% of the workforce in the United States. Adkins said Millennials have

been typified as “job-hoppers” prone to switch jobs. Six in ten reported that they are not only

open to new opportunities, but they also invite change. Called the least engaged generation in the

19

workplace, perhaps engagement could be better understood as a generation that has learned to

look out for “my career” and not assume “my company.”

Working adults, after years of disruption and re-invention due to the Covid pandemic,

have experienced an employment world that is deconstructed and reconstructing. More remote

work and virtual first, a remote and on-site blend, are available for those who work on laptops,

e.g., computer engineers. For those in customer service, jobs are not just changing, some jobs are

being eliminated with self-check outs, robots, and online shopping that shift work to warehouse

and delivery. For those in labor-based jobs, i.e., restaurant service, road construction, or

firefighting, physical presence continues to be required. The inability to hybridize certain

employment, the elimination of certain types of work, and the relocation of certain jobs to places

where workers may not be able to follow create unpredictability for working adults in the United

States.

Working Parents

In this study, I sought to learn the ways in which parent status, and further gender, were

related to the episode reports of mind wandering frequency and descriptive variables. While all

of us experience the unending nature of our tasks and daily routines, this is more pronounced for

parents. There is ongoing tension between parenting and working, a certain atelicity,

unfinished-ness (Irving, 2016, p. 83) as relational tasks recur and the core activities of parenting

and work, balancing back and forth, day in and day out, span decades. The feeding and serving

and cleaning in a household are in a looping cycle. One can drop a child at school only to worry

about her all day, every day. Each domain, work then home then work then home, takes “its

shift” but does not leave the other domain fully behind. In the wind down of the Covid

pandemic, when schools or daycares were reopening, work became remote, hybridized,

20

furloughed, or terminated, boundaries between home and work became blurrier than ever. Which

was important in the moment? A report Anita was working on at her kitchen table or her

seven-year-old melting down after hours of remote learning at the other end of that same table?

Dowling wrote, “There’s no playbook…. the problem persists for 18 year or more without ever

getting easier” (2019).

Working parents in the United States have undependable resources. Schools and

childcare centers have undergone operational uncertainties. Many have left the teaching

professions during and after the Covid pandemic, and school district leaders have said they are

“squeezed by the conflicting pressures set by new state mandates and parent demands” (Hill &

Destler, 2022). Job losses and working from home reinvented the proximity, even overlap, of

work to homelife. As closures and mixed openings continued, 617,000 women left the workforce

in September 2020 (Tappe, 2020, p. 1) in industries that typically employed women; working

moms, three times more likely than dads to take on housework and caregiving, made hard

choices about careers because children were at home and needed them there.

Historically, working parents have weathered the big things—wars, depressions,

pandemics—beyond the scope of a family’s control. The New York Times observed at the onset

of the coronavirus, “with children popping up in Zoom meetings and essential workers needing

to go to work despite having no childcare, it’s impossible to hide what has always been true:

raising children is a round-the-clock responsibility” (Miller, 2020, p. 1). Within this report, Dr.

Lakshmi Ramarajan, professor at Harvard Business School, was quoted, “our current situation is

posing fundamental challenges to the idea that personal and professional identities can be kept

separate” (p. 1). In its national analysis of 6.7 million caregivers, Blue Cross Blue Shield, a

nonprofit insurance company, reported that 26% of unpaid caregivers balancing work and family

21

due to Covid 19 have felt more stress and said that working parents have been the hardest hit by

this stress (LaMotte, 2020, p. 3). In a segment for PBS on impossibility of working from home

while supervising children at home, reporter Laura Santhanam wrote, “It doesn’t help that they

(working parents) must stare down the same uncertainty every day, that ‘everything could

change in a moment’” (2020, p. 7).

As Covid vaccinations and adaptations brought some normalcy, it has been an edgy

normalcy. Virus variants erupted as the pandemic morphed in the United States. As well, and

something that this dissertation was sensitive to, the pandemic’s isolation and struggle

experiences generated a certain post-traumatic stress and loss of trust and continuity with one’s

life before and after the pandemic. As reported on CNN, “The great reopening and return to

pre-pandemic life is a tale of two timelines—and parents are caught in the middle” (Tappe, 2021,

p. 1). It was not just disruption that changed family life. Coping with loss of “who we were” hit

everyone. Coping with the loss of a loved one hit particular families and communities, the people

who left us.

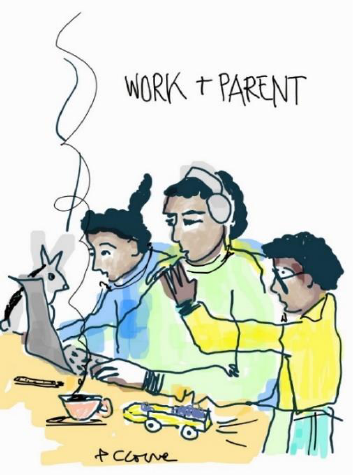

Carrying the weight of work and family responsibilities is a feat on rough ground. In

Figure 1.7, a working parent named Dan walked on the uneven ground of daily life and, all the

while, carried his work and family tasks and demands. What is not visible, perhaps as much to

Dan as those around him, were the mind wandering thoughts within his working parent mind.

When Dan closed his laptop, straightened his back, and looked out the window, was he still in

his task or was his mind somewhere else?

22

Figure 1.7

Working Dad You See. Working Dad Mind Wandering.

Note: Working Dad You See. Working Dad Mind Wandering. Copyright 2022 by Paula C. Lowe.

A Sample Not in a Lab

As previously stated within this chapter, leaders who recognize that they are leading

“whole persons” need information pertinent to the population they serve. The mind wandering in

daily life of working adults ages 25–50 has not been the focus of research. Predominantly,

investigators have studied the mind wandering of late adolescent university undergraduate

students doing contrived tasks in lab settings for college credit. This has been understandable for

research seeking to standardize for participant-level data analyses.

Life in the great outdoors is messy. Yet we need to venture forth because university lab

research designs cannot tell us about day-to-day life and may have generalizability issues for two

reasons. For one thing, researchers have asserted that mind wandering rates fluctuate across the

day (Smith et al., 2018) making sampling for an hour insufficient to account for this fluctuation.

For another, research using a convenience sample of late adolescent-aged college students may

not have produced results comparable to a working adult sample ages 25–50 as the human brain

23

is not fully developed until age 25 (Pujol et al., 1993). We do not know if the responses of late

adolescent subjects gave us mind wandering findings that are also descriptive of the mind

wandering of working adults. Without a focused inquiry, the mind wandering of working adults

may be mis-aggregated and assumptions about its frequency and negativity may be inaccurate

(Copeland, 2017).

Study Variables

This section provides a short introduction to mind wandering, intentionality, and the six

descriptive variables used in this research to characterize mind wandering episodes. These are

more fully presented in Chapter II.

Mind Wandering

Mind wandering was defined as an individual’s thinking that was not about what her or

she was doing. Within the research, mind wandering has been consistently defined across

research inquiries. It has been described as when the individual’s conscious experience is not tied

to the events or tasks one is performing (Seli et al., 2018b). Other terms have included

daydreaming (Antrobus et al., 1966), self-generated thought (Smallwood et al., 2011),

spontaneous thought (Christoff et al., 2016), and spontaneous cognition (Andrews-Hanna et al.,

2010). “Having one’s attention diverted away from the current task is such a common activity

that estimates suggest nearly 30%–50% of waking conscious experience is occupied by thoughts

unrelated to a primary task” (Franklin et al., 2013). Mills et al. (2018) surveyed the bounty of

mind wandering research and the loose agreement on definitions, most emphasizing an aspect of

mind wandering or even the dynamics, e.g., that mind wandering is a freely moving thought

across possible mental states (p. 21). Kane et al. (2017) cautioned that the investigation of mind

wandering in laboratory settings might be incomplete when considering mind wandering as

24

experienced in daily life in which respondents are not in a single environment with controlled

exposures to contrived tasks. The instruction for researchers from these sources was that we must

be explicit about the definitions used in a particular study. As well, researchers should assure that

they have asked respondents to differentiate between intentional and unintentional mind

wandering as this difference is central importance to this field of inquiry (Seli et al., 2016a).

To say someone is mind wandering because she is “off task” requires the term “task” to

be defined. Task was defined in this study as any kind of activity a participant was doing,

self-directed or other-directed, at the time of the notification. It could be running a 10k, typing on

a computer, cutting up vegetables, or other common activities in daily life. Certain researchers